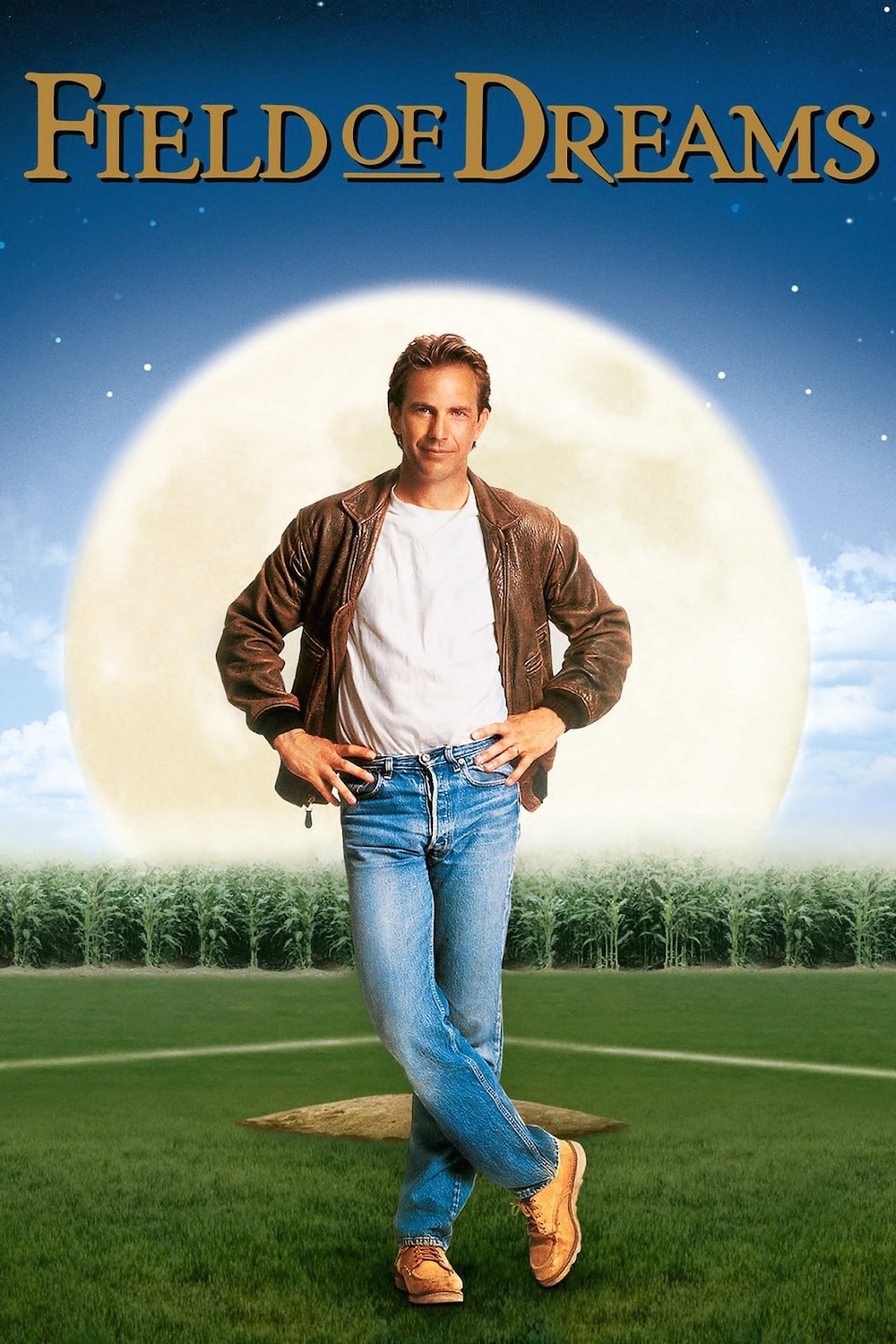

FIELD OF DREAMS (1989)

A farmer is inspired by a voice he can't ignore to pursue a dream he can hardly believe, to turn his ordinary cornfield into a place where dreams can come true.

A farmer is inspired by a voice he can't ignore to pursue a dream he can hardly believe, to turn his ordinary cornfield into a place where dreams can come true.

“If you build it, he will come.“

Ray Kinsella (Kevin Costner) stands stock-still in his cornfield, rigid with nerves. A disembodied voice has just spoken to him, not only distracting him from his farm work but also making him fear he’s lost his mind. As the voice persists, he’s forced to confront a series of questions: Where is it coming from? Why has it chosen him? Who is this “he” the whispers refer to? And exactly what does Ray need to build?

A baseball pitch, that’s what. After a vision of his objective is revealed to him, Ray convinces his wife Annie (Amy Madigan) to help him convert part of their cornfield into a baseball diamond. He hopes this will appease the spectral voices he hears in his head, but the purpose and reason for his mission remain elusive. However, when the ghost of baseball player ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson (Ray Liotta) arrives at the pitch, Ray realises his quest has only just begun…

Phil Alden Robinson’s Field of Dreams hasn’t aged well. It appears to have been tailor-made for Reagan-era audiences, with a shamelessly mawkish veneration of national sports and an exceptionally tone-deaf glorification of US history. However, the performances are compelling, albeit a tad overdone on occasion, whilst James Horner’s score provides a hypnotising aura that makes the film far more impactful than a baseball movie has any right to be.

The film opens with a lengthy voiceover. While uninspired and a touch lazy, it helps to establish the tone for the rest of the film: a story about the past, how it affects our understanding of our present, and the importance of family. Oh, and baseball, of course.

With a supernatural slant, Kevin Costner imagined the movie would become his generation’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). Director Phil Robinson seemingly shared this ambition, even hoping to cast James Stewart in a role. Though unsuccessful, he left a subtle tribute in the final product: a clip from Stewart’s film Harvey (1950), hinting at the thematic connection between the two works for those observant viewers.

It’s here that things start falling flat for non-American viewers. It’s a Wonderful Life is universally adored, something easily achieved as it conveys the importance of family and community over financial success or career fulfilment. While the tone in Field of Dreams is trying to emulate this feeling, the message differs slightly, causing a somewhat muddled film. Capra’s classic Christmas film is about our need for social stability, which one can find in a loving, empathetic network, whereas Robinson’s film conveys our need for… baseball?

No, perhaps that would be a bit too facetious—as most people would be quick to point out, there’s more to this film than just the overwhelming adulation of baseball. Field of Dreams is also about dreams and family, but the message is far muddier than its predecessor, meaning you don’t entirely buy into the film’s sentiment.

On top of that, for those of us who aren’t baseball fanatics, many of the film’s theatrical moments miss the mark, particularly when several characters start lauding the almost spiritual element of the game; there’s a fanaticism that doesn’t translate well when the sport is so intrinsically linked to the ineffability of the human experience.

However, this could also be a result of how the writer and director handle the game’s position in American culture. This is a film made by people who adore baseball, perhaps past the point of objectivity. Baseball becomes a symbol of US strength and unity, serving as the consolidating thread that has connected and will continue to connect a nation rife with division.

In this respect, Robinson appears to be posing questions about his homeland: what is this great country and where is it going? The problem lies in the fact that he offers rather simplistic answers, often using Terrence Mann (James Earl Jones) as a mouthpiece for his perspective. Mann, a disillusioned novelist and a prominent social activist in the 1960s, has since withdrawn from society, disillusioned by its renunciation of the causes that defined the era.

However, in a rather inexplicable turn of events, Mann becomes much more receptive to the idea of re-embracing society: he abandons his heartache and absconds to Iowa. True, he has indeed heard the voice that spoke to Ray, but his great fear of America devouring itself from within vanishes entirely. He too forgets about the social idealism that has dominated his life and work.

Even more strikingly, Mann argues that baseball embodies the innocence and integrity that define America. He sees it as a sport that seemingly confirms for him that his nation is fundamentally just, correct, and united. He cements this with what might be one of the most bewildering monologues I’ve ever heard. While it may well affect you, I’d argue it’s the result of Jones’s impeccable cadence rather than the material itself.

In this speech, Mann describes in vivid detail how people from all over the country will flock to Ray Kinsella’s baseball field: “They’ll arrive at your door as innocent as children, longing for the past. Of course, we won’t mind if you have a look around, you’ll say. It’s only $20 per person. They’ll hand over the money without even thinking about it: for it is money they have and peace they lack.” He ever so subtly slips in the stipulation that everyone must pay for their little piece of heaven; even paradise has an admission fee.

Though it masquerades as a story about the importance of family values, the film culminates in the monetisation of otherworldly magic, the commodification of heaven itself. As such, the explosion of consumerism which characterised the 1980s and Reagan’s America is provided a benediction. The irony is doubled by the fact that Mann delivers this monologue. As a dejected figure of the 1960s civil rights movement, he is actively encouraging the very form of capitalism that the period so vehemently opposed. The ethos of the ’60s is thus destroyed, supplanted by the worldview that came to define their new reality.

In this respect, we are sold the illusion of historical homogeneity. However, the truth is there was never a time when the country wasn’t steeped in vicious division and internal conflict. This, however, is the power of cinema, especially the works of Frank Capra. His films had a bewitching atmosphere that Field of Dreams so desperately tries to capture, an aura that crafted nostalgia as seamlessly as if it were made from clay.

The theme of nostalgia is similarly very present in this story. In the opening voiceover, we’re given an insight into Ray’s veneration of his father and, consequently, the era he lived in. As it happens, “Golden Age syndrome” pervades every generation: this classic 1980s film worships both the 1960s and the America that existed before the Great Depression. Considering shows like Stranger Things and It (2017) unabashedly exalt the styles and tone of ’80s cinema, it’s fascinating to see that each generation will extol the virtues of the one that preceded them, which, rather tellingly, was the one they never experienced as adults.

This cloying and uncritical reminiscing also characterises Mann’s monologue, creating a completely bizarre deification of the sport in the process. “The memories will be so thick they’ll have to brush them away from their faces. People will come, Ray. The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It has been rubbed out like a blackboard, rebuilt and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game: it’s a part of our past, Ray. It reminds us of all that was once good and it could be again.”

Here, we can see nostalgia’s insidious side: it completely erases any sense of objectivity. Rose-tinted spectacles prevent us from seeing all the blood that stains our history. Furthermore, the fact that it’s Mann delivering this eulogy to “good times passed” is immensely tone-deaf. Due to the fierce racial divide in 1919, Black players were excluded from participating in Major League Baseball. Why Terrence Mann suddenly believes that returning to a past era is what’s required, which stands in direct contradiction to his previous despair surrounding the lack of social progress in America, is baffling. Apparently, a field of dead baseball players is so potent that historical revisionism becomes an easy feat for even the most ardent social activists.

Perhaps the most effective exploration of a theme is dreams and their connection to regret when left unfulfilled. In one climactic moment, Ray speaks with the ghost of his deceased father, who asks him: “Is this heaven?” Ray answers solemnly, “No… It’s Iowa… Is there a heaven?” “Yeah…” his father smiles. “It’s the place dreams come true.” By the end of the story, Ray looks around at his cornfield, large farmhouse, and loving family—the epitome of the American Dream in Midwestern states. “Maybe this is heaven.”

The ending feels both propagandistic and rather saccharine. The first time Ray returns to the present day and admires it, he’s overwhelmingly pleased with the current era, ending his obsession with the nebulous Golden Age. After all, they’re living in the Golden Age, aren’t they? However, considering that Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) came out in the same year, it suggests the period wasn’t blissful for everyone.

Easily the most praiseworthy thing about the film is James Horner’s score. In a film lacking a sense of magic in the script, Horner’s theme elevates climactic moments tenfold. When Shoeless Joe first walks onto the baseball pitch, I felt goosebumps rise: the music truly makes you believe you’re witnessing something supernatural. While his ability to convey emotion was perhaps best demonstrated in his score for Braveheart (1995)—“Gift of the Thistle” will never fail to stir emotions in me—he achieves a similarly commendable feat here. In my opinion, his music is the film’s saving grace.

In watching older films, you can see how some are not quite timeless, but were instead simply products of their time. Field of Dreams feels like a film designed solely for American audiences during the Reagan era. The reverence for traditional sports often comes across as melodramatic, and the historical revisionism serves as a meretricious message about homogeneity in contemporary America. As a result, the film feels largely superficial. However, it might be best to avoid voicing that opinion to a baseball fan—particularly if they have a bat in hand.

USA | 1989 | 107 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Phil Alden Robinson.

writer: Phil Alden Robinson (based on W.P Kinsella’s novel ‘Shoeless Joe‘).

starring: Kevin Costner, Amy Madigan, James Earl Jones, Ray Liotta & Burt Lancaster.