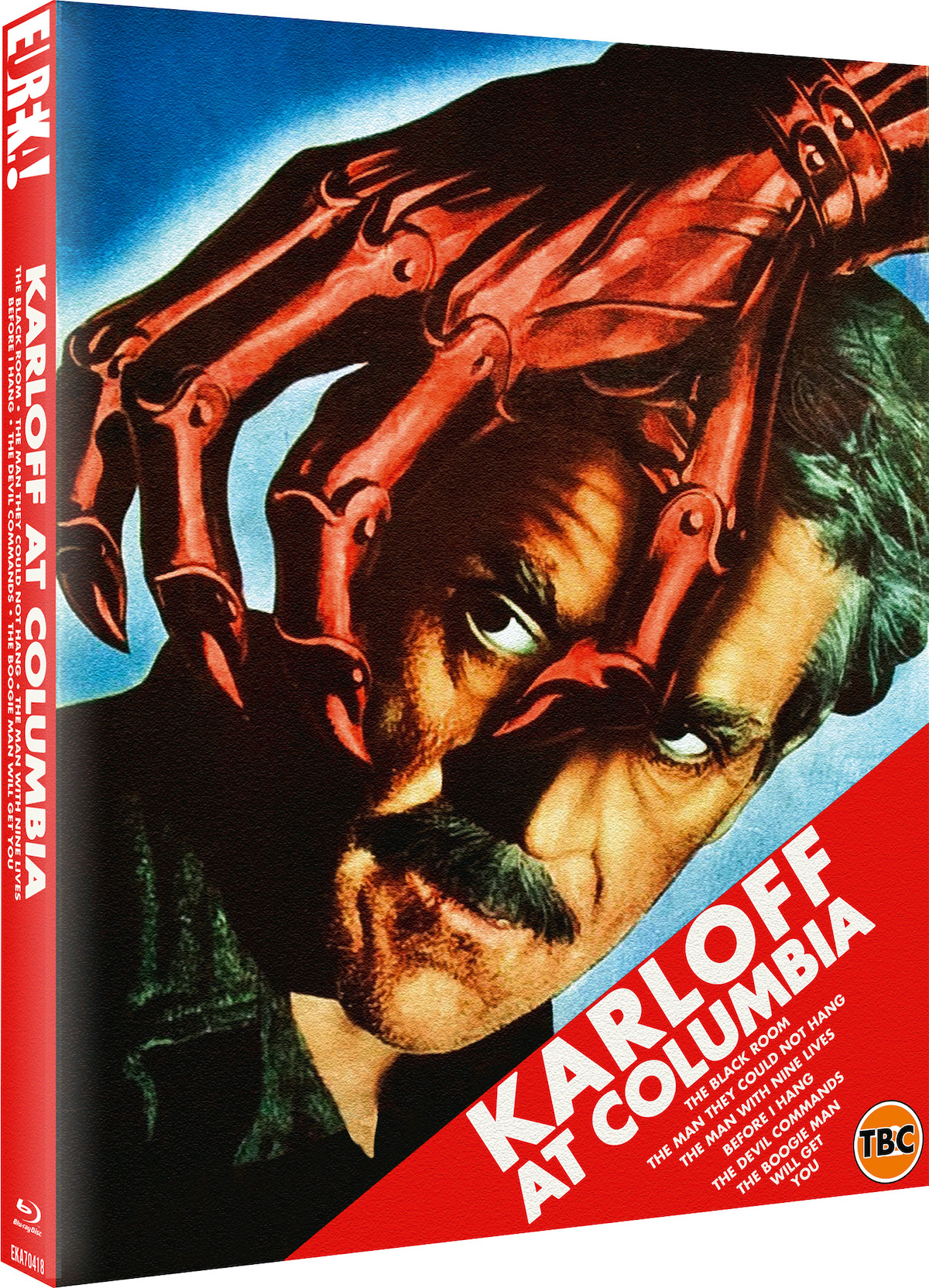

Karloff at Columbia (1935-1942)

Six films that horror icon Boris Karloff made for Columbia Pictures, a collaboration which produced some of his finest acting roles.

Six films that horror icon Boris Karloff made for Columbia Pictures, a collaboration which produced some of his finest acting roles.

Boris Karloff is forever linked with the most iconic movie monster of all time in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931), the horror classic that sparked off the Universal Pictures monster movie franchise that dominated the 1930s. Within a year he was given his first role with top billing when he worked again with Whale, behind some major prosthetics, as mad butler Morgan in The Old Dark House (1932). He was covered in rotting bandages as Imhotep in The Mummy (1932), heavily made-up for his lead in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), scarred and decaying for The Ghoul (1933), and reprised his role as the Monster for Whale’s sequel Bride of Frankenstein (1935). The same year he starred in the infamous adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven (1935), this time with only half his face disfigured.

Even when we couldn’t see Karloff’s visage, he managed to emote. He could act with his whole body and imbued what could’ve been mere cyphers with genuine depth of character. Famously, he brought a humanity to Frankenstein’s Monster that elicited sympathy and informed many subsequent portrayals.

All those physically demanding performances captured the public imagination to such an extent that the promotional material for The Black Room (1935), made it a selling point that we would get to see the actor ‘unmasked’. Obviously, nobody had really noticed him in the 80 or so films he’d already appeared in, which included the critically acclaimed Five Star Final (1931), before Whale ‘discovered’ the go-to monster man of Hollywood actors!

The Raven had been the third of a trilogy loosely inspired by Poe’s Gothic stories starring Bela Lugosi that had started with Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932). Karloff had also appeared—without any special makeup—in The Black Cat (1934). However, The Black Room evokes the atmosphere of Poe far better than any of those earlier films, although it never claimed connection to the author. It was also the first of Karloff’s contracted and credited appearances for Columbia and is the star attraction of this new Blu-ray box set from the Eureka Entertainment that collects all six films he made with the studios.

Ignoring an ancient prophecy, evil brother Gregor seeks to maintain his feudal power on his Tyrolean estate by murdering and impersonating his benevolent younger twin.

The Black Room is a fine example of both a top-notch costume melodrama and a classic Gothic horror. One thing that’s immediately clear from the grand scale of the sets and vast crowds of extras in the opening shots, is a respectable budget. Columbia weren’t making a B Movie here, though some contemporary critics dismissed it as such. The studios were trying to live up to their newfound reputation after the phenomenal success of Frank Capra’s comedy It Happened One Night (1934), which had just won them the five top Academy Awards.

The Black Room was also the perfect vehicle for Karloff to break away from his run of monster roles and showcase his skills as a character actor. You can tell he’s really relishing a challenging double role as identical twins with very different personalities!

There’s great rejoicing for the birth of a son and heir to the local Baron (Henry Kolker), but when the attending physician announces that twins have been born, the master of the house seems crestfallen and it’s not just because the second boy has a paralysed right arm. Seems the hereditary title has been handed down over generations that have avoided having two male children. For it’s an old family prophecy that the line will end with two brothers and it’s written that the younger will kill the older, in the Tyrolean castle’s ‘black room’. The simple solution? Brick-up the accursed onyx-walled chambre to ensure the prophecy cannot be fulfilled.

We see the brothers, grow up through a brief montage of them attending the graves of their parents in an increasingly decrepit, deliciously Gothic graveyard. Through the dates on the headstones we learn that 20 years have passed since the death of their father. So, that takes us into the early-19th-century when the younger twin, Anton de Berghman (Boris Karloff) is summoned home to the family seat by the Baron Gregor de Berghman (also Karloff).

It seems that Arthur Strawn’s original story owes a great debt to Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination. There are twins in The Fall of the House of Usher, also doomed to end a cursed family line. I don’t want to spoil things too much for those who are coming to this marvellous movie afresh, but there’s also a ‘pit’ involved and a sinister mechanical contraption that bring to mind The Pit and the Pendulum. There’s a Premature Burial and, of course, the bricked-up room motif is central to The Black Cat, as is animal intervention that finally brings justice. Poe fans will be in their element.

In the village tavern, knowingly named ‘Le Chat Noir’, we overhear the disgruntled locals plotting to do away with the baron who they proclaim to be a “tyrant and fiend”. Apparently, not only are his taxes too high, they suspect he’s responsible for the disappearance of a series of women from the surrounding villages. One can guess where their bodies may be ending up and there’s a definite nod to the Bluebeard fairy tale.

Karloff does a great job of rendering the three characters of the twins. Hang-on, my maths doesn’t add-up does it? He plays the scowling Gregor with a brash swagger and a slovenly stoop, whereas Anton stands tall, his smile isn’t lopsided, but warm and honest and their ways of speaking are distinct. Of course, they’re similar. They’re identical twins after all, but we don’t need the apparent conceit of the paralysed arm to tell them apart. So, we know that’s been a set-up all along for a later plot twist. More than one, in fact.

The third role emerges as Karloff cleverly plays Gregor imitating Anton. Subtle and beautifully observed, it’s all in the eyes. There are glances and ‘micro-expressions’ he lets the camera glimpse, but not the characters he shares the scenes with. Probably because I have recently revisited Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (1980), it reminded me of the great central performance by Tatsuya Nakadai in which he too plays one identical character imitating another, subtly creating a third fusion personality that isn’t quite either… Perhaps, given more time, pretending to be the good Anton may have changed evil Gregor for the better? But no, he takes irretractable and unredeemable action pretty early in the proceedings!

The identity swap is all a ploy to escape the wrath of the mob who, in fine Gothic tradition, try to storm the castle with pitchforks demanding justice for the missing women. Also, he intends to add at least one other woman to his collection. Thea (Marian Marsh) is the beautiful daughter of an old family friend, Col. Paul Hassel (Thurston Hall). She was repulsed by Gregor but charmed by Anton, despite being betrothed to the dashing Lt. Albert Lussan (Robert Allen). So, all Gregor has to do is convince everyone he’s Anton and then he can inherit the lands and marry Thea. Just two obstacles need to be dealt with first: Lussan, who’s fiercely devoted to Thea, and Tor (Von), Anton’s devoted and fierce hunting hound.

This richly detailed story plays out against the backdrop of amazing sets designed by Stephen Goosson, who was Head of Production Design at Columbia at the time. The castle interiors are fantastic. The many arches, staircases and shadowy alcoves offer plenty of opportunities that cinematographer Allen G. Siegler takes full advantage of. There are some striking shots that exploit the split level and depth of the sets. His lovely grey tones and rich textures are nicely shown off in this high-definition Blu-ray edition.

Although the sets are impressive enough, many are extended by the gorgeous backdrops and matte paintings of Jack Cosgrove. He’s one of the masters of the ‘lost art’ who would lend his magical touch to many films, notably Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) for which he helped create the Californian coast and Manderley itself using a combination of miniatures and matte painting. While we’re on the visual effects, Roy Davidson deserves a shout-out for the many split-screen process shots that made it possible for Karloff to act opposite himself. Even with today’s high-definition, its almost impossible to see the join.

The collection of the day’s top talents in both the cast and crew are all pulled together under the direction of Roy William Neill who approaches this as anything but a B Movie horror. He also made good use of access to the extensive, 40-acre, studio backlot with its ready made ‘foreign’ locations, including the Tyrolean village we see here. Audiences of the day may have recognised some landmarks from other films that had been shot there including Cecil B. DeMille’s biblical epic King of Kings (1927), seminal ‘creature-feature’ King Kong (1933), and She (1935).

It was an amazing resource from the first ‘Golden Age’ of cinema, and yet it would all be gone four years later when it was intentionally torched to provide the burning of Atlanta backdrop for Gone with the Wind (1939)—movie madness! Throughout, Neill uses mirrors whenever he can and also plays with symmetry, sometimes dictated by the split-screen ‘butterflying’ the action of some scenes. He’s not just playing visual games with the audience and uses mirroring as an integral narrative device to reveal one of the key plot points.

Roy William Neil was already a veteran director having started his career in the silent era with more than 75 films already under his belt. Nowadays, he’s probably best remembered for directing Basil Rathbone in a dozen Sherlock Holmes films throughout the 1940s. The Black Room still stands out as a high point, even in such a long and illustrious career.

It’s surprisingly modern, it’s marvellously macabre, and the well-crafted suspense still works. It was Karloff’s favourite role. For any genre fan, it’s a must see that’s been criminally neglected until now. So, kudos to Eureka! It makes the £40 box set seem like great value, especially when you consider the other five Karloff films (four of which are great) that come with it across two discs with excellent extras…

USA | 1935 | 68 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

When Dr Savaard’s experiment using an artificial heart is interrupted by the short-sighted authorities, his volunteer dies, and he is condemned to death. He vows vengeance if he can survive his own hanging.

All helmed by producer Wallace MacDonald, the next four films are known collectively as ’The Mad Doctor Cycle’, as each stars Karloff as a scientist whose ambitions to better the world either go terribly wrong or are drastically misunderstood and ultimately lead to murder and mayhem. They all sit comfortably in the science-fiction arena and feel rather like extended episodes of The Outer Limits (1963-65)—which goes to show how ahead of their time they were.

To varying extents, they share prominent elements of crime drama and supernatural horror. They also discuss important ethical and philosophical dilemmas and so, rather appropriately, are aligned with Mary Shelly’s 1818 gothic novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.

This is an intellectually entertaining film despite it having an overall dark tone. Dr Henryk Savaard (Karloff) is a brilliant surgeon who’s built an apparatus that can take over whilst a patient’s heart is stopped to allow surgery upon it. There’s even a suggestion that it could be replaced with a new one, or even a miniaturised version of his invention. Bear in mind that this is nearly 30 years before Christiaan Barnard would actually perform the first successful human heart transplant, so we’re straight into sci-fi territory.

Savaard is talking about heart bypass surgery, pacemakers and artificial hearts, but the scientific community isn’t ready to risk human trials. So, aware that every year the procedure is delayed costs the lives of those it could save, his research student agrees to have his heart stopped and restarted by Savaard’s machine as proof of concept.

Unfortunately, the student’s fiancée isn’t as convinced and panics, calling the police to stop the experiment. They arrive to find the medical student seemingly dead and Savaard, quite honestly admits that he has indeed killed him. He seems quite pleased that expert witnesses have turned up to watch the resuscitation but, not understanding the situation, the police arrest the doctor for murder.

Act two veers away from medical thriller into a courtroom drama as evidence is heard and the jury deliberate. On the testimony of the Coroner and a damning summing-up by the manipulative District Attorney (Roger Pryor), Savaard’s found guilty and sentenced to hang. Before the doctor is taken, away he delivers an eloquent speech that covers some serious points about scientific ethics before morphing into the kind of speech a witch may’ve given as the pyre was lit under them.

He points out to the jurors who convicted him that there will come a time when they may have to watch a loved one die, knowing that they executed the one man who could’ve saved them. And when their own time comes, they will meet their maker knowing that Savaard’s invention could well have cured them too.

Whilst awaiting his appointed time of execution, he entrusts his apparatus to Dr Stoddard (Joe De Stefani) a medical associate who helped with the project. He also requests that his dead body be donated to science and nominates Stoddard to take charge of it after execution… no points for guessing where that’s leading.

The third act perverts the popular template set-out by Agatha Christie where a group of people are gathered, and cut-off from the outside world, before they begin to get knocked off, one by one. Here, the Judge, District Attorney, Coroner and jurors are all invited to Savaard’s well-appointed house. Since his execution, the successfully revived doctor has spent his time turning his mansion into a death trap.

On each of the invites that brought them there is a time which Savaard, via an intercom system, explains is their specific time of death. They just have to wait their turn. In essence he has done to them what they did to him, or any person condemned to be executed.

Each victim is tricked into being complicit in their own death as they panic to avoid it. One tries to escape by climbing a metal grille which becomes electrified at the exact minute of his predicted demise. Another is manipulated into trying to phone for help only to be pierced by a spring-loaded spike concealed in the earpiece. This same method of remote murder is used by another mad doctor, 33 years later, in Dr Phibes Rises Again (1972), the sequel to The Abominable Dr Phibes (1971), which owed much of its inspiration to this seminal movie about a deranged doctor seeking retribution.

The interesting thing about both Savaard and Phibes is that they were not the bad guys to begin with and, as they see it, their victims are being served their just deserts. This goes some way to absolving the audience for finding entertainment in what should be rather grim. Possibly the only thing that remains disappointing is that his plan to kill the assembled guests doesn’t play out and we are denied the enjoyment of further inventive killings.

USA | 1939 | 64 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

A medical researcher visits the deserted home of a pioneer in cryogenic science who disappeared 10 years earlier and finds him frozen in ice but still alive.

Boris Karloff plus the mad doctor theme already capitalised on the huge popularity of the Frankenstein franchise and The Man They Could Not Hang was successful enough to spawn a sequel within a year. In The Man with Nine Lives, Karloff returns, this time as another pioneering doctor, Kravaal, who could almost be Savaard again. After all, we know he can be successfully reanimated!

There’s a real sense of stylistic continuity with Nick Grindé back in the director’s chair and cinematography again by Benjamin H. Kline. Together, they make everything look pretty classy, employing deep shadows to enrich atmosphere and extend sets in the film noir style, which had really caught on in Hollywood. Perhaps this was due to the influence of filmmakers escaping the rise of the Nazis in Europe and bringing with them the almost sculptural use of shadows typical of German Expressionist cinema.

Karl Brown is back as the main scriptwriter, with some story input from Columbia’s stable of writers, and throws in even more sci-fi inventiveness, this time round, peppering it generously with gothic tropes. It seems that Dr Kravaal, along with one of his patients and several others, disappeared 10 years ago in mysterious circumstances from his island retreat at Silver Lake. Dr Tim Mason (Roger Pryor, playing the good guy this time) enlists the help of nurse Judith Blair (Jo Ann Sayers) to investigate, in the hope of discovering more about the ground-breaking work Kravaal was doing in the fields of cryogenics and cancer treatment which he hopes to continue.

They finally arrive at the decaying mansion which acts as a metaphor of the body—a recurring trope in gothic fiction—and just as time acts on living flesh, so the neglected house has suffered the ravages of tide and time. After falling through the rotten floorboards, Blair and Mason find a secret passage in the basement that leads a long way down to a secret chambre deep in the ground. A dusty laboratory, equipment still in situ, draped with cobwebs. There’s a building sense of claustrophobia and the action now unravels in the dark basement. If we were to apply Joseph Campbell’s ‘hero quest’ analysis, we are deep in the abyss from which the hero will emerge with the secret that can redeem them and save the world…

It seems that Dr Kravaal had bought the isolated mansion because of its unique location and the geology below. Behind a huge steel door, they discover an ice cave. It seems the passage was an old mine shaft, abandoned when it reached the face of an underground glacier. Basically, a natural deep freeze provided for free. The chambre looks just like the inside of a giant freezer in need of defrosting and within, they find the bodies of Kravaal and the others, frozen solid. Mason knows enough about the experimental process of medical freezing to successfully thaw out the doctor with lashings of hot coffee! The we get the story, told in flashback, of how he came to be in such a situation and there is an echo of Savaard’s story from the first film.

Again, Karloff manages to make his doctor sympathetic and layered. The fulcrum of madness is not so clearly defined this time round and though he does murder someone, it’s in the heat of the moment and quite understandable and, after the balance is tipped he’s still trying to do ‘the right thing’ even though he knows he may be personally doomed. One roots for the bad guy, because he’s been put in his unenviable situation by men who were worse.

USA | 1940 | 74 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

A physician on Death Row for a mercy killing is allowed to experiment on a serum using a criminals’ blood, but secretly tests it on himself…

Producer Wallace MacDonald got the team back together for the third in this thematically linked series. This time the medical foe is aging and death itself. We join the story in the courtroom as the silver-haired and mild-mannered Dr John Garth (Karloff) is sentenced to death for murder.

In his speech to the jury, he explains that he’d been researching a serum to reverse the aging process and had been working with a volunteer who was in great pain due to age-related illnesses. He’d manage to prolong life, but his patient’s pain had only increased until he’d begged the doctor to help him find peace. His failure made him feel obliged to help the old man die and release him form agony. Of course, in the eyes of the law, this was premeditated murder… a serious and sombre opening.

Garth is given three weeks before his date of execution and asks that he be allowed to continue his medical research in prison. It’s a race for life against death and as his approaches, he begins to make real progress. But he needs young healthy blood to complete the anti-aging serum. His pleasant demeanour has earned him respect from the death row warden (Ben Taggart) who has also allowed his scientific associate, Dr Ralph Howard (Edward Van Sloan) to assist him. They even manage to secure a sample of blood from an executed man. On the day of his own execution, he decides to test the serum on himself, reasoning that if there are any adverse effects, then it really doesn’t matter.

Meanwhile, his daughter, Martha (Evelyn Keyes) has been lobbying governors and state officials for clemency and as he’s being led from his cell the warden breaks the news that she’s been successful. He’s been granted a reprieve. On hearing this, Garth collapses. When he wakes, he notices that colour has returned to his hair and he no longer needs his reading glasses. His serum has worked but we soon learn that it’s not without side-effects.

The speculative science in the first two films, and the first half of this one, has been solid for its day. Now, though, we venture into some dubious territory as we’re asked to accept that the murderous impulses of the executed criminal who ‘donated’ his blood have somehow been transferred to the rejuvenated doctor. But, hey, a similar hokey premise had worked for Conrad Veidt in The Hands of Orlac (1924) and would in several other films to come, including Alan Parker’s Angel Heart (1987).

Karloff once again carries the film with his multi-layered performance and, perhaps drawing upon his experience in The Black Room, is able to portray two personalities inhabiting the same form. One is good, the other evil and there’s a definite Jekyll and Hyde element. It’s a well-paced, clearly told story that gets genuinely creepy in parts and may be one of the earliest incidents of the ‘black gloved killer’ trope. It remains grimly entertaining and again discusses ethical issues that are still relevant today.

USA | 1940 | 62 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

A scientist becomes obsessed with the idea of communicating with his dead wife.

Wallace MacDonald shook things up with a new team for the fourth in Columbia’s ‘mad doctor cycle’. Edward Dmytryk directs a script by Robert Hardy Andrews, based on William Sloane’s 1939 novel The Edge of Running Water. The cinematography is by Allen G. Siegler whose name one might recognise form The Black Room.

“Why are they afraid of my father’s house?” asks the narrator over a lovely model shot of a storm-lashed cliff-top mansion. This is the voice of Anne Blair (Amanda Duff) who recounts the tragic events leading up to her mother’s death and how her father, Dr Julian Blair (Karloff), became obsessed with trying to communicate with her departed spirit using scientific methods. He had been experimenting with recording the brain waves of the living.

Again, this was absolutely cutting edge at the time. German scientist, Hans Berger, had recorded the first human ‘brainwaves’ in 1924, inventing the electroencephalogram (EEG), and his discoveries had only been tested and confirmed in 1934. This opened up whole new avenues of non-invasive neurological study.

Possibly the maddest of the mad doctors gathered in this box set, but more of a mad professor than a medical doctor, Dr Blair begins experimenting with fringe physics and is clearly inspired by Tesla and Edison’s race to build an apparatus that could communicate with the dead. Yes, that’s a part of real history.

Around 1918, the inventor Nikola Tesla (the one the electric cars are named after) reported that his radio apparatus was picking up voices speaking a language he couldn’t decipher. To begin with, he considered the possibility that he might be eavesdropping on extraterrestrial communications. It was suggested that they may’ve been voices ‘from beyond’. Believing this to be an actual possibility, Thomas Edison, intended to beat his rival to the patent for radio that could establish two-way communication with the dead.

In a 1920 interview published in The American Magazine, Edison is quoted as saying “I have been at work for some time building an apparatus to see if it is possible for personalities which have left this Earth to communicate with us.” He was eventually confident enough to invite scientists and psychic mediums to the laboratory to observe a demonstration of his spirit phone.

It didn’t work. Nothing at all. Edison wasn’t discouraged, though, and never stopped trying to perfect it. He even contracted a lab technician to continue with the experiments after his own death when he would be able to assist from ‘the other side’…

With its New England scene, journalistic narrative and a wild mix of mysticism, physical science and quantum theory, The Devil Commands conjures a Lovecraftian weirdness that sets it aside from the other films here. Blair enlists the help of Blanche Walters (Anne Revere), an unscrupulous medium whose methods have been debunked as fake but, nonetheless, has unique ability to channel and modulate electricity through her brain. Blair believes that she may be able to tune in to the resonances of the disembodied ‘souls’ and use the brains of the freshly dead as transceivers to establish two-way comms.

This leads to a wonderfully wacky set up for an electric séance where corpses acquired from local crypts are sat in a circle wearing special helmets. The production design delivers exactly what one wants from a mad scientist’s lab and the insane plot makes this film stand out from the others of the ‘mad doctor cycle’ which seem more like variations on a theme.

USA | 1941 | 65 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

A young divorcee tries to convert a historic house into a hotel despite its oddball inhabitants and dead bodies in the cellar.

This really doesn’t sit well in this collection and is only here for completeness, being the final film Karloff made to honour his contract with Columbia. It’s an unabashed and unsuccessful pastiche of Frank Capra’s classic black comedy Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) but with no Cary Grant and none of the later film’s panache. You may be wondering how it can be a pastiche if it was made first?

The Boogie Man Will Get You was a rushed production based on a script that Edwin Blum wrote in less than four weeks. It was intended to ride on the success of the Broadway stage play of Arsenic and Old Lace, penned by Joseph Kesselring, in which Boris Karloff starred as the psychopathic ‘doctor’ Jonathan Brewster. The production was shot on a tight schedule during a hiatus in the play’s run when Karloff would be available.

The cast really try to bring energy to the proceedings, but without the material to work with in the first place they resort to almost slapstick levels of physical comedy. Larry Parks gives us a particularly spectacular pratfall, but even that looks too painful to be funny. Jeff Donnell brings loads of energy to her role but it’s all just too loud and brash. The lines are shouted with great gusto, backed-up with big expressions and gestures. One of the ‘anything-but-funniest’ moments features a sleep-walking maid (Maude Eburne) who thinks she’s a chicken. There’s also a gruff groundsman (George McKay) who loves his pigs more than people.

There’s no real story, just a setting in which a bunch of unrelated zany stuff happens. The tricked-out house, with secret passages behind paintings, is explained in a throwaway line. An undercover inspector from the Historical Society (Don Beddoe) explains that Benedict Arnold had hidden there to escape capture. Arnold was a traitor of American Revolutiony, who swapped sides to fight for the English. In the US, his name became a byword for turncoat or traitor. Perhaps the name-drop would’ve seemed ‘edgy’. There’s also a great lab in the basement, but nothing to rival what we just saw in The Devil Commands.

Karloff, parodying his ‘mad doctor’ personae, and co-star Peter Lorre, as a multi-tasking local official, are the only two things really worth watching it for. But even Lorre doesn’t look like he really wants to be there, and doesn’t seem to understand why he has a kitten in his pocket either. It makes no sense. I dunno, perhaps I was missing something, but I strongly recommend anyone with the box set giving this one a miss! It really wrecks a binge-watch but, thankfully everyone involved seems to want to get it over with and tear through the script. Nevertheless, its modest 66-minutes are still a bit of an endurance test. My advice? Seek out Arsenic and Old Lace instead which, ironically was filmed whilst Karloff was tied-up with the stage show, so his part was played by Raymond Massey.

USA | 1942 | 66 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

directors: Roy William Neill (Black), Nick Grinde (Hang, Nine, Before) • Edward Dmytryk (Devil) • Lew Landers (Boogie)

writers: Arthur Strawn & Henry Myers (story by Arthur Strawn) (Black) • Karl Brown (story by Leslie T. White & George Wallace Sayre) (Hang) • Karl Brown (story by Harold Schumate) (Nine) • Robert Hardy Andrews (story by Jarl Brown & Robert Hardy Andrews) (Before) • Robert Hardy Andrews (story by William Sloane) (Devil) • Paul Gangelin (story by Hal Fimberg & Robert B. Hunt) (Boogie)

starring: Boris Karloff • Marian Marsh, Robert Allen, Thurston Hall (Black) • Lorna Gray, Robert Wilcox, Roger Pryor, Don Beddoe & Ann Doran (Hang) • Roger Pryor, Jo Ann Sayers, Stanley Brown, John Dilson & Hal Taliaferro (Nine) • Evelyn Keyes, Bruce Bennett, Edward Van Sloan, Ben Taggart & Pedro de Córdoba (Before) • Richard Friske, Amanda Duff, Anne Revere, Ralph Penney & Dorothy Adams (Devil) • Peter Lorre, Max Rosenbloom, Larry Parks & Jeff Donnell (Boogie).