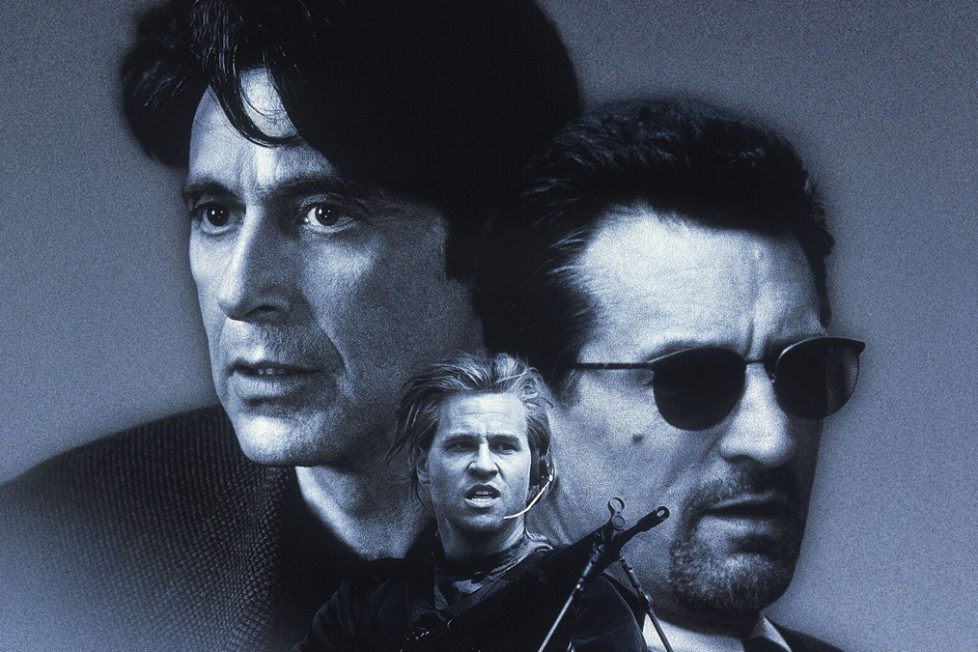

HEAT (1995)

Michael Mann’s Heat is essentially a ‘cops and robbers’ story. But, of course, it’s also a hell of a lot more than that. Unlike many of Mann’s greatest films—in particular Manhunter (1986), Miami Vice (2003), and more recently Blackhat (2015)—Heat is a film that was critically and commercially successful on release, and now regarded as a modern classic. His films post-Heat would only further alienate audiences as he insisted upon mixing his evident commercial instincts with greater experimentation.

But what infuriates critics of his recent films was on show in 1995, too. 20-years might have seen Mann push his ideas further, but the beauty of Heat lies not only in its expert execution of genre tropes and portrayals of archetypes, but also the psychologies crammed into those archetypes and its uniquely balanced narrative. Although there are several high-octane robbery/shoot-out set pieces in Heat, they’re given no greater weight than the professional thief—Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro)—discussing his inner turmoil. McCauley is out of jail, and he’s not going back. That doesn’t mean he’s on the straight and narrow, though—it simply means he can take the all-or-nothing road.

His nemesis on the other side of the law is Detective Hanna (Al Pacino). He’s a loner surrounded by people. But rather than spending time with his wife and stepdaughter, he chooses to spend his time in the company of the dead people whose murders it’s his job to solve. He works in robbery and homicide, and that’s where his path crosses with McCauley’s. The two have much more in common than what separates them. They’re united by a mutual understanding and a professional commitment to the life each leads, no matter what sacrifices this necessitates. As McCauley puts it: “I’m alone. I’m not lonely.”

The first of only two occasions on which the two adversaries meet one another comes halfway through the film. It’s an incredible scene, eclipsing the major gun fights that come both before and after this very simple meeting of minds in a grubby restaurant. They outline their positions, dancing around one another while each barely gives an inch at all. The lone wolf mentality and a twisted sense of integrity that each recognises in the other is plain to see. It’s the slow building nature of their conversation that says so much about the film as a whole and Mann’s films generally. He might like a confrontation and a gun fight, but that doesn’t mean he can’t construct a simple conversation in a way that lays two characters bare, yet also seems to reveal nothing at the same time.

The two men at either end of that table are also played by two of the most respected actors of the second half of the last century—Pacino and De Niro. It would be impossible to discuss the film without also discussing these two. It’s fair to say that neither one of them is at the height of their career in 2015, but they’ve both never been better than they were 20-years ago in Heat. Has either produced a performance even half as good as these since? I think not. De Niro encapsulates the character the way we know he can but often doesn’t. Nobody could play this man of virtue and violence better—he’s streetwise but methodically quiet; low-key but explosively violent. Pacino’s performance walks a similar tightrope, managing to make his good guy both sympathetic and, ultimately, not that good.

The style of Mann’s films has always been a point of contention for many critics. The almost classical way he treats his archetypes and plots seems very old territory, and it is. Mann’s films aren’t breaking any ground when it comes to narrative development. He takes the audience on a thrilling ride, but it’s not an unexpected one. This then rubs up against Mann’s stylisation in a way that many can’t stand. His style is constantly modern. In his early films (and his later ones) he used electronic synths to lend a pulsating intensity to the acts of violence and extremity. He would later go on to innovate with digital filming techniques. But in Heat, he takes a slightly different turn. Instead of using the electronica to suggest violence and heightened suspense as he did in Manhunter and Thief, he uses it in the quiet moments. This gives the film a different tone, making it feel even more relentless and immersed in the underworld of these characters more so than ever before. As soon as the violence starts, the music stops. Instead, we get a heavy barrage of gunfire that never seems to let up either.

This murky criminal underworld is very particular to Mann. One of the scenes that the director uses repeatedly in his films is the main characters (often with their lover or family) placed at the edge of the world. This edge is often a hill, cliff or by the sea. It suggests that the land has run out and they have nowhere else to go. These scenes get to the core of what’s best about Heat. These characters are running out of time, space, options, everything. No one tells these stories quite as well as Michael Mann.

starring: Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Tom Sizemore, Diane Venora, Amy Brenneman, Ashley Judd, Mykelti Williamson, Wes Studi, Ted Levine, Jon Voight & Val Kilmer.