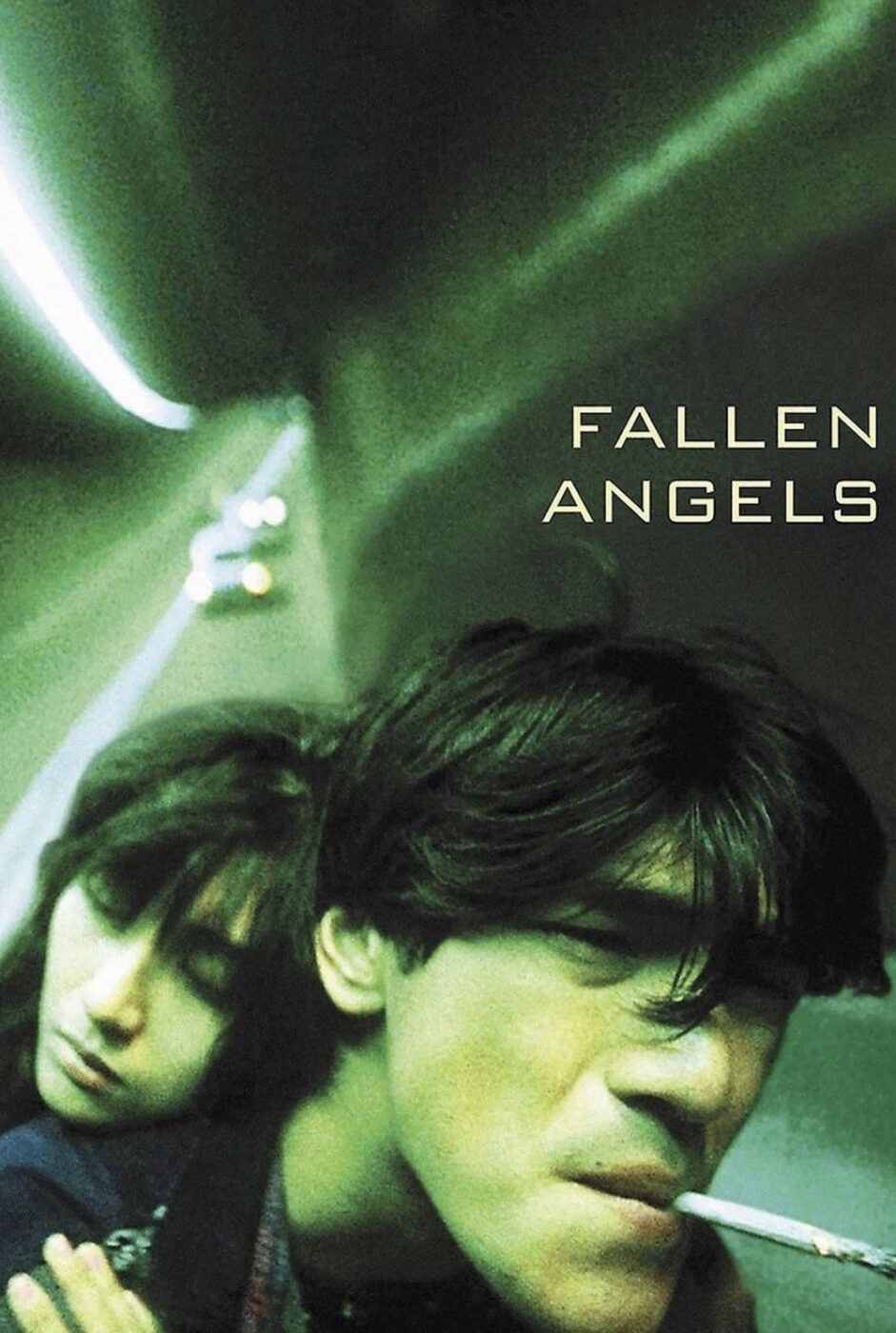

FALLEN ANGELS (1995)

An assassin goes through obstacles as he attempts to escape his violent lifestyle despite the opposition of his partner, who is secretly attracted to him.

An assassin goes through obstacles as he attempts to escape his violent lifestyle despite the opposition of his partner, who is secretly attracted to him.

While cinema can be edifying, most audiences turn to it as a form of escapism from the monotony of daily life into worlds more alluring and more profoundly beautiful than our own. Few filmmakers conjure that spell with greater artistry than Wong Kar-wai, the Hong Kong auteur whose omnipresent sunglasses have become nearly as iconic as his œuvre. Since debuting with his atmospheric gangster reverie As Tears Go By (1988), Wong has not merely developed an idiosyncratic aesthetic but constructed an entire cinematic cosmos. He has cultivated a universe steeped in chance encounters, unfulfilled desires, and alienated melancholy, all rendered in some of the most striking visual and musical textures ever committed to celluloid.

Although his sophomore effort, Days of Being Wild (1990), signalled his true artistic emergence, it was Chungking Express (1994) that announced him to the world as a stylistic visionary. With its blend of frenetic handheld camerawork and pop-infused exuberance, the joyously inventive diptych of loosely connected love stories distilled the fleeting vibrancy of Hong Kong on the cusp of political transition. Quentin Tarantino’s endorsement further ensured Wong’s embracement among Western cinephiles, but it was not until In The Mood for Love (2000) confirmed his calibre for international audiences and solidified him as one of the greatest filmmakers in the illustrious history of Asian cinema.

Both Chungking Express and In The Mood for Love have become international sensations since their initial release, and their reputations have only deepened with time. In 2022, both works were enshrined in the British Film Institute’s prestigious poll of the ‘100 Greatest Films Ever Made’. In the Mood for Love is perhaps Wong’s most widely celebrated project, and its influence reverberates throughout Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation (2003), Nicholas Winding Refn’s Drive (2011), and Barry Jenkins’s If Beale Street Could Talk (2018). However, among the more devoted cinephiles, Chungking Express remains a perennial rival for the title of his masterpiece. However, between these two canonical landmarks lies a more enigmatic entry into Wong’s filmography.

Originally conceived as the third narrative strand for Chungking Express before the projects were separated due to their cumulative length, Fallen Angels / 堕落天使 emerged as its shadowy companion piece and spiritual sequel. After recognising the third segment’s tonal dissonance threatened to disrupt the buoyant rhythms of Chungking Express, the auteur transformed the idea into a standalone project. The result is a neon-soaked meditation on urban disconnection and fleeting intimacy that simultaneously enhances the emotional texture of its predecessor and asserts a singular identity. Throughout the years, Fallen Angels has cultivated an ardent cult following as the brooding sibling to Chungking Express. Yet, despite being infused with Wong’s hallucinatory nocturnal aesthetic and aching portraits of loneliness, it’s often positioned as an overlooked oddity when discussing his intoxicating distillations of romantic despair.

Set amidst the neon-soaked labyrinth of Hong Kong’s underworld, Wong Chi-Ming (Leon Lai) is a professional assassin who conducts his affairs through a strikingly enigmatic female partner (Michelle Reis). Despite managing his finances, maintaining his cramped warehouse apartment, and orchestrating his assignments, the two have never met. Their relationship is mediated entirely through phone calls, coded exchanges, and impersonal drop-boxes. However, this arrangement only deepens her obsessive fascination with him. She learns about his mysterious nature by finding disparaging clues while searching through his garbage, lingering longingly in his bed, and indulging in fantasies of an intimacy that remains stubbornly out of reach. When Wong realises their relationship will forever remain suspended between erotic tension and emotional distance, he decides to sever their professional ties after carrying out one final assignment.

The second narrative thread follows the antics of He Zhiwu (Takeshi Kaneshiro), a petty criminal who shares a cramped apartment with his widowed father (Man-Lei Chan). Inexplicably mute from the time he ate an expired can of pineapple chunks, the petty criminal makes a living by roaming the streets at night and breaking into convenience stores. While foisting his appropriated wares onto unsuspecting strangers, he crosses paths with the temperamental young woman, Charlie (Charlie Yeung). She’s heartbroken that her former boyfriend abandoned her for his alluring temptress, Blondie(Karen Mok). Drawn into her emotional turbulence, Zhiwu accompanies her on an obsessive quest to hunt her phantom rival through the city’s nocturnal labyrinth. However, when Charlie abruptly vanishes from his life, Zhiwu channels his solitude into filmmaking. He begins filming his father at work in their dilapidated family restaurant in an attempt to hold onto something enduring amid the metropolis’s fleeting connections.

Attempting to parse the intricacies of Fallen Angels is rather like explaining an abstract painting. There are many individual brushstrokes and visual cues to notice and dissect, but the instinctive mood of the piece lies in the atmosphere collectively conjured through its texture and fluidity. Much like he did previously with Chungking Express and would later accomplish with Happy Together (1997), Wong Kar-wai combines the fractured romanticism of the French New Wave with the gritty shimmer of cross-processed fashion photography to craft a distinctly Asian meditation on impermanence refracted through a vérité cinema of hand-held spontaneity focused on the transience of modern urban life. The filmmaker’s methods epitomise the often-debated question of style versus substance, but for Wong, the two are inseparable. The incessant play with frame rates and asynchronous narration are not just stylistic flourishes, but the very grammar through which the filmmaker articulates that life is lived in fleeting encounters and missed connections.

With the aid of Christopher Doyle’s (In The Mood for Love) cinematography, Fallen Angels could be considered the most visually audacious entry into Wong’s filmography. Since beginning their collaboration with Days of Being Wild and continuing through 2046 (2014), it has become one of the defining partnerships in contemporary Asian cinema. Doyle’s creative use of extreme wide-angle lenses, handheld camerawork, and unusual compositions crafts a disorienting yet hypnotic rhythm, transforming Hong Kong into a surreal labyrinth that’s simultaneously intimate and alienating. Shot largely at night in cramped interiors and among neon-soaked streets, the city is rendered as a dreamlike landscape with a fluorescent glow that reflects the turbulent confusion and desperate longings of the characters.

Despite its frenetic visual energy, Doyle often experiments with shutter speed and frame manipulation to elongate moments and create a hallucinatory sense of impermanence. During one particular restaurant sequence between Zhiwu and Charlie, as she procrastinates over her former boyfriend, he repeatedly leans his head on her shoulder, becoming increasingly infatuated with her. In what could otherwise be a mundane encounter is transformed into something monumental and suspended through Doyle’s techniques. In the background, a time-lapse accelerates the passage of the customer’s ordinary life, while in the foreground, Zhiwu and Charlie move with a languid slowness. The resulting juxtaposition does more than create a visual spectacle, it dramatises the emotional asymmetry of two characters stuck in time as Zhiwu desperately attempts to preserve a fleeting instant of connection with Charlie.

Working in great tandem with its visuals is a resonating soundtrack compiled by Frankie Chan (Goodbye My Love). Wong’s deployment of music is more pronounced and integral than in any of his previous works. Just as The Mamas and the Papas’ classic “California Dreamin’” became inseparable from the thematic fabric of Chungking Express, the carefully selected needle drops here serve as an emotional architecture for a narrative that resists conventional linearity. Laurie Anderson’s ethereal rendition of “Speak My Language” and Robison Randriaharimalala’s propulsive remix of Massive Attack’s “Karmacoma” infuse their respective sequences with a tonal specificity that prevents them from drifting into stylistic excess. Most significant is the recurring presence of Shirley Kwan’s tender cover of Teresa Teng’s “Forget Him”. Its reappearance mirrors the unresolved longing between Wong and his business partner while creating a melancholic sense of inevitability, suggesting that these urban drifters are caught in a devastating cycle of desire and loss.

Beneath the neon-soaked haze and disjointed narrative structure, Wong crafts a profound meditation on the impermanence of loss and the fragile intersections that momentarily tether solitary souls adrift in the modern city. As the characters circle around the void left by broken attachments, their lives brush against one another elusively until they finally connect. Although Wong drifts toward an inevitable fate, his female partner and Zhiwu have a chance encounter that ultimately brings them together. Both broken by the world around them, the two fallen angels find solace in the tenderness of the present. Their nocturnal motorcycle ride distils Wong’s overarching thesis into a single sequence. Pressed against Zhiwu, she confesses “I haven’t been so close to a man for a while. But I’m feeling such warmth this very moment”. The acknowledgment is both tender and tragic, for she knows that the present, however temporary, possesses its own transcendence. As the tunnel dissolves into morning light, Wong asserts his philosophy that the world is not defined by permanence, but by the intensity of fleeting encounters.

While Chungking Express is often enshrined as one half of Wong Kar-wai’s masterwork, there’s no telling why Fallen Angels frequently languishes in the shadows of critical discourse. Although it lacks the narrative cohesion of its predecessor, it’s an equally engrossing follow-up that deliberately rebounds recurring visual motifs, reused locations, and similar narrative themes through a cracked mirror. It’s a cinematic fever dream that solidifies Wong’s stature as an auteur singularly attuned to the fleeting and the ephemeral. Filmed with his characteristically breakneck kinetic bravura, it’s a profound meditation on missed connections, fleeting embraces, and the ache of memory. Suspended in a liminal state of yearning and alienation, its characters never arrive at fulfilment. Yet, in their endless search, they embody the very essence of our own restless search for meaning amid impermanence in a transient world. If Chungking Express and In the Mood for Love are celebrated as Wong’s canonical peaks, then Fallen Angels must be seen as an essential counterpart.

HONG KONG | 1995 | 99 MINUTES | 1:85:1 | COLOUR • BLACK & WHITE | CANTONESE • MANDARIN • JAPANESE • ENGLISH

writer & director: Wong Kar-Wai.

starring: Leon Lai, Michelle Reis, Takeshi Kaneshiro, Charlie Yeung, Karen Mok & Man Lei-Chan.