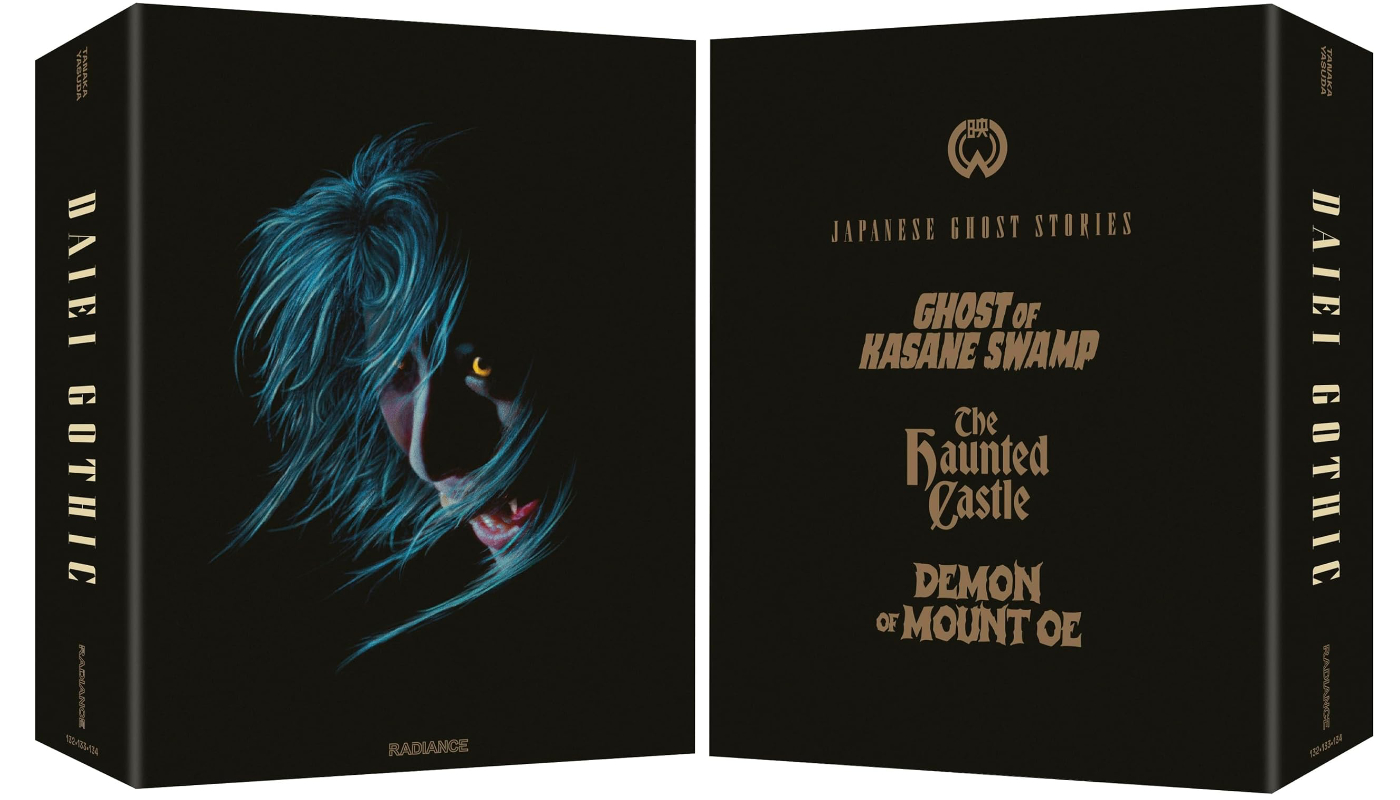

‘Daiei Gothic Vol.2—Japanese Ghost Stories’ (1960-1970)

Three classic Japanese ghost stories are brought to the screen by masters of the genre, Tokuzo Tanaka and Kimiyoshi Yasuda.

Three classic Japanese ghost stories are brought to the screen by masters of the genre, Tokuzo Tanaka and Kimiyoshi Yasuda.

Following on from last year’s excellent box set Daiei Gothic: Japanese Ghost Stories (1959–1968), Radiance Films bring another trio of Japan’s classic supernatural stories to light, just in time for the spooky season. However, although Halloween’s now a big thing in Japan, ghost stories have traditionally been enjoyed during the sweltering summer months when families gathered in cooler interiors with the shades lowered and shared tales that would chill them to the bone. Golden Week marks the start of summer, when several national holidays come in rapid succession at the beginning of May. The triumvirate of major studios—Toho, Toei and Daiei—were in fierce competition for a share of the cinema audience, often premiering their big budget star vehicles during this lucrative time. Ghost stories proved to be reliably popular among filmgoers, just as they had been centuries ago on the kabuki stage or performed as bunraku puppet plays. The three movies presented in ‘Daiei Gothic Vol.2’ are all based on stories that became popular during the Edo period and have continued to evolve ever since with character reshuffles and setting changes.

The first movie presented here, The Demon of Mount Oe / 大江山酒天童子 (1960) was a Golden Week release. It’s a lavish crowd-pleaser showcasing Daiei’s top talent in a clever story that melds together several popular supernatural stories in ways that would’ve surprised and delighted its audience. The middle movie, The Haunted Castle / 秘録怪猫伝 (1969) is a fine example of the bakeneko subgenre, a cornerstone of J-Horror cinema featuring demonic shape-shifting cats that could manifest as seductive women with an appetite for human flesh and blood. It reworks one of the best known and often retold examples that purports to be inspired by historical events. The third film, Ghost of Kasane Swamp / 怪談累が渕 (1970) is the darkest and most modest production. Made while Daiei was facing imminent bankruptcy, it retells one of Japan’s oldest known ghost stories, a cruel tale of human betrayals and supernatural vengeance. Another essential triple-bill from Radiance that makes for perfect Halloween viewing!

A legendary monster seeking revenge is assisted by a gigantic demon ox and a huge spider!

Having reviewed Rashomon (1950), I was thrilled to realise this was a freewheeling reinvention of a 10th-century tale of the legendary samurai Watanabe no Tsuna, scourge of demons, referenced in the dialogue of Akira Kurosawa’s acclaimed movie. An impressive recreation of the Rashomon Gate even features prominently as the hideout for a band of fearsome bandits, but those who think they already know the associated stories are in for a big surprise.

The film opens with some striking kabuki-style mechanical effects as sections of the set disassemble and move aside to facilitate scene changes instead of edits. We are introduced to The Four Heavenly Kings: Sakata no Kintoki (Kôjirô Hongô), brandishing his signature huge axe; Urabe no Suetake (Narutoshi Hayashi), a master of the bow; Usui no Sadamitsu (Ryûzô Shimada) and Watanabe no Tsuna (Shintarô Katsu), who both seem comfortable with their katana. The four legendary heroes are joined by the lone warrior, Hirai no Yasumasa (Jun Negami), and the general of the Genji samurai, Minamoto no Yorimitsu (Raizô Ichikawa), also known as Lord Raikô.

These mythic characters would have been as familiar to Japanese audiences as King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table are to the British, and the actors were all well known, with Raizô Ichikawa already a fan favourite poised on the cusp of superstardom. When these legendary warriors burst into the lair of the Oni Shuten-dôji, catching the crimson-skinned horned demon off guard, the monster’s decapitation would have been the expected outcome of the story. But wait, this is just the pre-title sequence. Apparently, the ‘true story’ of Shuten-dôji and the Four Heavenly Kings has yet to be told…

The Four Heavenly Kings were historical persons, just as King Arthur and his knights were, but, similarly, they have become mythical as the history has been eroded by fantasy. Fuji Yahiro’s carefully balanced script is loosely based on the classic tale of “The Goblin of Oeyama”, a.k.a “Tale of Shuten-dōji”, as retold by prolific author Matsutarō Kawaguchi, who was known to collaborate on adaptations of his work and to write original screenplays—notably Kenji Mizoguchi’s classic Ugetsu (1953), the film that pioneered Daiei’s blending of the jidaigeki genre with the supernatural. The Demon of Mount Oe fully embraces this concept, creating what was a fresh fusion of the jidaigeki period drama, kaidan ghost story, and supernatural yōkai tales—something for everyone to enjoy. This had never been done so wholeheartedly before and probably paved the way for Masaki Kobayashi’s classic portmanteau Kwaidan (1964).

Tokuzô Tanaka had been assistant director on both Rashomon and Ugetsu, so he’d learnt from the best, but The Demon of Mount Oe was still a big production for Daiei to entrust to a comparative newbie, being just his fifth feature as director. Their trust paid off as he acquits himself deftly, combining action, epic battle scenes, spooky sequences, ground-breaking mechanical effects and experimental wirework, resulting in something quite different to any of Daiei’s prior productions. And it remains top-notch entertainment.

The image quality of this 4K restoration is gorgeous. I mean, just look at the rich colours and silk lustre of the kimono on show. Sadly, there’s some rather obstinate and obtrusive noise on the soundtrack that I feel could have been reduced with some careful digital remixing. The script is strong enough to cut through this, but it does get in the way of engaging with some of the earlier scenes. One eventually acclimatises… I tried imagining it was an acoustic backdrop of heavy rain, which sort of suited the Gothic atmospherics. It’s only a problem during the dialogue and doesn’t detract from the often-grandiose score by Ichirô Saitô that masterfully segues between traditional instrumentation and modern orchestration.

The superb cinematography of Hiroshi Imai adapts to the new challenges of colour and innovative VFX. He’s just as comfortable handling action sequences on location as the more intimate, set-bound interactions. He’s best known as a repeat collaborator with director Kazuo Mori, including three of the better entries in the Shinobi franchise: Shinobi 3: Resurrection (1963), Shinobi 6: The Last Iga Spy (1965), and Shinobi 7: Mist Saizō Strikes Back (1966). He also had a hand in several supernatural movies, including two notable contributions to Daiei’s classic Yōkai Monsters sequence—the middling Spook Warfare (1968) and the excellent Along with Ghosts (1969).

If The Demon of Mount Oe has any significant flaws, it’s that it tries too hard to please everyone, but the success of its initial theatrical run indicates that it achieved Daiei’s goals. Though the novelty VFX would have been a big draw at the time and suitably impressed audiences, some of the practical effects may seem rather quaint nowadays, but they still effectively serve the storytelling. Japanese audiences would no doubt appreciate the nod to the traditional stagecraft of kabuki theatre, which often employed ambitious mechanical effects and clever illusions. For me, this really adds to the film’s charm and encourages deeper engagement as the viewer must use their own imagination to meet the movie magic halfway.

Toho’s kaiju franchise that followed the surprise success of Godzilla (1954) was a major challenge to Daiei, who make a brave attempt to do something similar here. They don’t take the man-in-rubber-suit route but create a couple of excellent human-scale puppets. One is the totally reimagined demonic form of the Kidomaru (Toshio Chiba) that resembles a rhinoceros crossed with an ox, which can fly.

We first meet the Kidomaru when Lady Nagisa (Fujiko Yamamoto) unwittingly summons it with her sad song performed as a parting ‘gift’ for the villainous Kampaku (Eitarô Ozawa), who is passing her on to Lord Raikô, “from one man’s hand to another, like a doll without a soul,” as she will later sum up the transaction. At this point, we don’tknow her backstory, nor does she know why the Kidomaru tries to abduct her, because the demon’s attempt is thwarted by the axe-throwing skills of Sakata no Kintoki, Raikô’s loyal retainer sent to escort her.

So, without giving too much away, it turns out that Nagisa’s ex-husband, a noble samurai, was disposed of by the lustful Kampaku but somehow survived and is now known as Shuten-dôji (Kazuo Hasegawa), self-proclaimed demon king of Mount Oe, who commands a horde of fearsome bandits and has a small demonic retinue at his service, including the Kidomaru and the lovesick sorceress Ibaraki-dôji (Sachiko Hidari).

This completes the line-up of the top Daiei contracted talent. This was truly a star-studded cast, and with their two most popular actors taking the lead roles, it’s inevitable that Raizô Ichikawa, as the heroic Lord Raikô, and Kazuo Hasegawa, as the ambiguous Shuten-dôji, will face off for the finale. However, the dénouement may be unexpected as the narrative veers away from the source materials in a series of satisfying twists and turns along the way.

I really enjoyed the reworking of traditional tales, especially a sequence based on the story of “The Goblin Spider”, which was first translated by the folklore scholar Lafcadio Hearn and appeared in the hugely influential series of Japanese Fairy Tales published by Takejiro Hasegawa from 1885-1922. This involves a demon spider that takes the form of a Buddhist monk who can ensnare his victims in webs shot from his hands, rather like Spider-Man. The battle between several samurai and the demon in its true form is marvellous, with the giant spider puppet spewing sparks and cinders, and realised faithfully as depicted in the famous storybook illustrations. To fully appreciate the cleverness of the script and Fuji Yahiro’s talent for invention, it helps to know a few of the tales that have been invariably tweaked to create a fresh narrative. To see such core folklore reinvigorated and kept alive in this way must have thrilled its domestic audience even more.

JAPAN | 1960 | 114 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

A young woman turns to the supernatural to wreak revenge on a murderous warlord.

Whereas The Demon of Mount Oe is a rollicking great action-adventure full of big-budget spectacle, The Haunted Castle is a more contained affair laden with atmosphere and, of the three films here, is certainly the most Gothic in style and content. Nearly a decade later, Tokuzô Tanaka is confident and comfortable in the director’s chair, and the 40 or more features he’d directed during the interim included two notable entries in the Sleepy Eyes of Death franchise, three Zatoichi films, eight of his Bad Reputation sequence and—-recently released by Radiance—The Betrayal (1966) and The Snow Woman (1968), which is included in their first Daiei Gothic box set.

By the mid-1960s, there was a global appetite for the lurid colour and textured shadow of a new Gothic aesthetic established by Mario Bava in Italy, Roger Corman in the US, and Hammer in the UK, which was at its peak producing the classic horror films that defined its brand. The Haunted Castle can stand shoulder to shoulder with their best titles. Of course, any mention of Hammer Films conjures vampire connotations. Japan didn’t really have any vampire mythology to draw upon, though Toho was poised to import Dracula, at least in name, for its so-called Bloodthirsty Trilogy (1970–74). Japan’s mythology did have plenty of Oni that ate human flesh and bones, but the closest thing to vampires were the bakeneko—malign ghost cats that in some stories drank the blood of their victims. The international resurgence of the vampire brought these old stories back into cultural consciousness.

Shôzaburô Asai, fresh from penning Along with Ghosts, based his script for The Haunted Castle on one of the most famous tales to feature a bakeneko, known as The Nabeshima Disturbance. In the traditional telling, a despotic daimyō, or clan lord, uses a game of Go as an excuse to kill one of his retainers he suspects of plotting against him. The murdered man’s distraught mother then kills herself, and the family cat drinks her spilt blood and becomes a bakeneko that then thirsts for both blood and vengeance on her behalf. It appears in the castle of the daimyō every night, at first tormenting him with yowling, eventually possessing members of his family or shapeshifting into their doppelgängers. In the mid-19th-century, the story was embellished and adapted into stage plays and with each retelling gradually became conflated with older tales of bakeneko, some dating back to the 12th-century.

Lord Nabeshima (Kôichi Uenoyama) of Saga Castle is out riding with Lord Hanzaemon (Kôjirô Hongô) when his attention is attracted by a large parasol shading some picnickers. We learn they are Lord Matashichirô (Akihisa Toda) and his sister Sayo (Mitsuyo Kamei). A visually striking bird’s-eye shot, with the red of the parasol occupying a large section of the frame, introduces them. This composition will be echoed a little later when a similar proportion of screen space will be filled instead with the red of a pool of blood.

It transpires that Matashichirô once stood to inherit Saga Castle and its domain, but through some political manoeuvring around a trivial matter Nabeshima, who had been the clan’s chief retainer, managed to oust the family and pays them a token stipend. However, now that Sayo has grown into a beautiful young woman, he seems keen to make amends and take her as a concubine, but Matashichirô will not agree.

Again, we have men discussing women as chattels, and in feudal Japan this would’ve been the situation. On the whole, women had very little independence and relied on men for their security and social status. This may be why most of the famous ghosts of Japan in age-old stories, paintings, plays and now films—are female. They had little power in life and were often abused and victimised. So, a supernatural second chance to wield power and exact vengeance is not only a satisfying trope but makes a sharp social statement.

Ironically, Nabeshima’s retainer Lord Gyôbu (Rokkô Toura) is also vying for power in a plot that involves his sister, Otoyo (Naomi Kobayashi), who is already a concubine, providing an heir that will inherit the castle and its domain. A new, younger concubine would threaten this plan, and so he sows paranoia that Matashichirô is the one plotting to regain his family’s power over the domain.

When Matashichirô is invited to the castle for a game of Go, Tama, his black cat, jumps into the palanquin ahead of him and scratches his hand as if to warn him against going. Instead of scolding the animal, he surmises that it may be ill, comforts it and suggests that Sayo tend to it. As well as foreshadowing some of what’s to come, this little dramatic device establishes the blind Matashichirô as a pleasant and caring fellow.

It’s as if the cat somehow knew that Gyôbu had a plan to manipulate the events of the evening in a way that would result in Nabeshima killing Matashichirô and dumping his corpse down an abandoned well. He then serves an eviction notice, exiling Sayo from the domain. While in the traditional tale, it’s the victim’s mother who kills herself and creates the bakeneko, here it’s the younger sister who commits suicide. As Tama laps up Sayo’s blood, she uses her dying breath to instruct the black cat to exact vengeance. The realistically copious blood is used to great compositional effect while making a visceral connection with the audience. Mitsuyo Kamei’s emotive performance is both potent and restrained. The cat is also very good here.

So, the scene is set for a series of escalating supernatural attacks on the occupants of Saga Castle as Tama becomes a demon and grows in strength. Her haunting begins with the tinkling of the tiny bell at her collar. Not so scary, one may assume, but in the dimly lit chambers and corridors and with an inspired director, it becomes rather sinister. The foleyeffects in the hands of spooky sound specialist Tôru Kurashima work beautifully in tandem with a sympathetic score from Chumei Watanabe. Then maids begin to turn up dead at the end of tiny paw-print trails left in blood. The concubines begin behaving suspiciously, such as developing a craving for fresh fish. And why not throw in a haunted Goboard to help madden Nabeshima?

The cinematography of Hiroshi Imai is outstanding, particularly the painterly use of deep chiaroscuro. To fully appreciate some of the inventive shots as intended, one needs to have a very big screen or sit very close to the television with all the lights out. In some scenes, the screen is left mainly dark with the lamp-lit action confined to a small area as the viewpoint tracks slowly across. In a darkened auditorium, the ghostly scene would seem to hover, moving through space in a way that would dissolve the obvious barrier of the screen. The events appear to occur in a boundless space that the viewer shares—an inspired exploitation of cinematic language.

Tokuzô Tanaka poetically subverts visual linguistics throughout. He tends to avoid too many edits by using camera movements in their place or having actors move into or out of the shot. Instead of zooming in, which he does from time to time, he may effectively change the screen ratio by using structural shadows or perhaps a doorway to create a frame within a frame.

For example, during a conversation between Sayo and Matashichirô, their faces are lit by a lantern that fills the centre of the frame while they face each other from either side. Rather than cutting between them as they speak in turn, our eyes are guided to make the edits. Not only is The Haunted Castle visually breathtaking, but the performances are consummate all round, and the story manages to make many profound observations regarding the often-indiscriminate damage caused by generational cycles of betrayal and revenge. Best of all, it manages to do all this while building an uncanny yet poetic atmosphere as well as remaining highly entertaining.

JAPAN | 1969 | 84 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

A blind masseur sleeps with the wife of a samurai, who catches them in the act and kills them, but the murdered couple return as vengeful ghosts.

A change of director for the third movie, with Kimiyoshi Yasuda taking the helm with another Shōzaburō Asai script; this time an uncompromising retelling of one of Japan’s oldest ghost stories that still echoes through modern J-Horror. Yasuda had already made Ghost Story: Depth of Kasane (1960) 10 years earlier, which is a solid take on the tale, shot in black and white with some memorable imagery that may have been quite harsh in its day but remained within expectations of the genre. Although this remake repeats recognisable scenes it did not comply with those expectations. Its characters are even more amoral, the violence more brutal and in colour, and this time around the freedoms of the sixties had relaxed cinema censorship to allow the inclusion of sex scenes. Indeed, some distributors insisted

Seijun Suzuki’s Gate of Flesh (1964) is cited as the first major film made in Japan to feature erotic nudity. Around the same time, small independent studios sprang up, producing cheap nudie films, known as Pinku-eiga (ピンク映画) or simply ‘Pink Films’ which were low-budget sexploitation screened in backstreet cinemas. However, the bigger studios recognised the market potential and, at the end of the 1960s, Toei started putting out films for mature audiences, often set in the criminal underworld where sex and violence could be integrated into the plot. In the early-1970s they marketed such erotic thrillers in three new sub-genres of Sensational, Shameless, and Abnormal.

So, Daiei were ahead of the curve with Ghost of Kasane Swamp which, although not too explicit, has some scenes with the briefest partial nudity as well as sexualised violence and rape that would have surprised if not shocked mainstream audiences of the day. The following year, 1971, Nikkatsu would introduce its Roman-porno marque—which may not be what you’d think. I recently learnt more in the context of a handful of late entries into the genre from Takashi Ishii: 4 Tales of Nami (1992–94).

The film opens with the aftermath of a seemingly unrelated double murder of a naked woman and her lover, still partially tangled in blood-soaked sheets. Blind rent collector Soetsu (Kenjirô Ishiyama) simply turns back when he hears the name of the dead man. We next see him at home with his two daughters, the good Osono (Matsuko Oka) who still lives with him, and the runaway Oshiga (Maya Kitajima) who has returned to ask for the loan of a substantial sum of money. She won’t say what she needs it for, but we later find out she intends to buy the debts of the madame of the brothel where she now works, so she can take over. Soetsu flatly refuses her request.

Next, things get really messy when he turns up to collect back payments from a struggling samurai (Saburô Date) catching him in flagrante with the housemaid (Reiko Kasahara) while the man’s neglected wife (Teruko Omi) listensfrom the other room. Undeterred, Soetsu presses for his payment and the irritable samurai tells him that his wife will pay their debt. Of course, with no money and few possessions, how can the wife pay up? So, she offers herself to the landlord. In addition to an opportunity for a little, decidedly unerotic raunch, this becomes the inciting incident. The samurai makes a point of entering the room and, as was the right of a samurai, killing the adulterous wife and her lover. A neat solution to his present predicament.

Here, we have a repeat of the blind bald man being struck down by a sword strike that leaves a cleft in his pate. Visually, it’s the same trope as we just saw in The Haunted Castle. Okuma, who is perhaps the one character without any bad intentions, witnesses the murder and provides a moral lens for the viewer to take in and consider the situation. She will appear later at another pivotal point to directly challenge the morality of another character, with tragic consequences.

The samurai orders his two henchmen to dispose of the bodies in the nearby swamp. But even if we didn’t know this was a ghost story, the title is a dead giveaway so, we can be sure that the spirits of the landlord and the wronged wife will not rest easy. It isn’t long before they return and cause the samurai to fall on his own sword. This is all in the first act, so where do we go from here? Well, the samurai’s son arrives to identify the body. Initially, it appears that he’ll fulfil the role of amateur sleuth, but it’s soon made clear that he’s only interested in collecting any inheritance.

He’s furious that his father has already squandered it all and when he hears that Soetsu had been miserly, stashing away vast amounts of cash, he sets his sights on stealing that. His henchmen, sent to search the debt collector’s home, fail to find the cash, which has already been taken by Oshiga to buy her brothel. However, they do find the husbandless Osono, now fatherless and defenceless, and while they’re there both take turns to rape her…

From the outset, it’s made clear that the overarching belief of nearly all the characters is that life is cheap and both cash and flesh are currency. This pervading pessimism is the narrative’s main problem as it becomes increasingly difficult to like any of this array of unsavoury, morally bereft characters. There are no good guys here except the supernatural forces of karma that ensure everyone finally gets some comeuppance.

The bold cinematography by Chikashi Makiura goes part way to mitigate the unrelenting misanthropy by keeping things visually interesting. Some scenes are played out with no set at all. The actors are picked out by spotlights that bring them in and out of total darkness. It’s a very theatrical effect and would also create the same effect we saw in the far superior The Haunted Castle where characters would become untethered from materiality and seem to hoverin the same empty void we occupy. There are also some surprising, visually abrupt uses of freeze-frame combined with graphics, such as an illustrative blood splash superimposed over the face of Suetso’s ghost, and the samurai’s madness represented by his lone figure seemingly falling through a lava lamp. Clearly, this is of its time and director Kimiyoshi Yasuda embraces the experimentalism of the new wave which is also enhanced by a great experimental score from one of Daiei’s more prolific composers, Hajime Kaburagi who provided the music for Seijun Suzuki’s excellent, and truly avant-garde, Tokyo Drifter (1966).

JAPAN | 1970 | 84 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

directors: Tokuzô Tanaka (Demon, Haunted) • Kimiyoshi Yasuda (Swamp)

writers: Fuji Yahiro (based on Ōeyama Shuten Dōji by Matsutarō Kawaguchi) (Demon) • Shôzaburô Asai (Haunted) • Shôzaburô Asai & Enchô San’yûtei (Swamp)

starring: Kazuo Hasegawa, Ichikawa Raizō VIII & Shintaro Katsu (Demon) • Kôjirô Hongô, Naomi Kobayashi & Mitsuyo Kamei (Haunted) • Saburô Date, Kenjirô Ishiyama & Teruo Ishiyama (Swamp).