TOKYO DRIFTER (1966)

After his gang disbands, a yakuza enforcer looks forward to life outside of organized crime but soon must become a drifter after his old rivals attempt to assassinate him.

After his gang disbands, a yakuza enforcer looks forward to life outside of organized crime but soon must become a drifter after his old rivals attempt to assassinate him.

The first time I saw Tokyo Drifter was with friends at the college arts cinema in the late 1980s. We’d heard it was an ultra-hip gangster movie from Japan. There was a 1960s revival going on so this fitted the bill beautifully with its pop-art aesthetic and cool suits. Of course, when it was made, it wasn’t retro at all but up-to-the-minute and cutting-edge. So much so that the director Seijun Suzuki was given a proper dressing down by the executives at Japan’s Nikkatsu studios. They thought it was incomprehensible!

After that first viewing I, too, remembered it as a psychedelic, freewheeling experience, but back then we didn’t have any method of re-watching to check. We all agreed it was great fun and held our attention. It left a lasting impression. For a while after, we’d greet each other with a somewhat cheesy exchange that had struck us as incongruous yet hip: “Hey, Shooting Star!” to which the reply would be “Don’t get familiar.”

Years later, I jumped at the chance to see it again at Nottingham’s Shots in the Dark crime film festival. Quentin Tarantino was a headlining guest and had a hand in selecting the films being screened. In post-Tarantino cinema (most of) Tokyo Drifter made perfect sense as a groundbreaking work of genre-busting genius. It was clearly a major influence on Tarantino himself, which he freely admits, along with other energetic filmmakers coming out of the ‘80s New Wave like Jim Jarmusch, John Woo, and Japan’s own Kitano ‘Beat’ Takeshi.

Tokyo Drifter has now been digitally restored on high definition Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection. They’ve released DVD and Blu-ray versions previously, but this time the colours are super vibrant, as intended, and the soundtrack crisp and clear. This is great news because cinematographer, Shigeyoshi Mine, who often worked with Suzuki, pulls out all the stops with this film. There are several sets, all with distinct lighting styles and colour palettes. The scenes shot on location vary from baroque nighttime low lighting to scenes played out against a glaring snow-blanketed landscape. He utilises filters experimentally; their diffuse edges slicing across the frame to give an almost constructivist composition, splitting the expansive wide shots into sections.

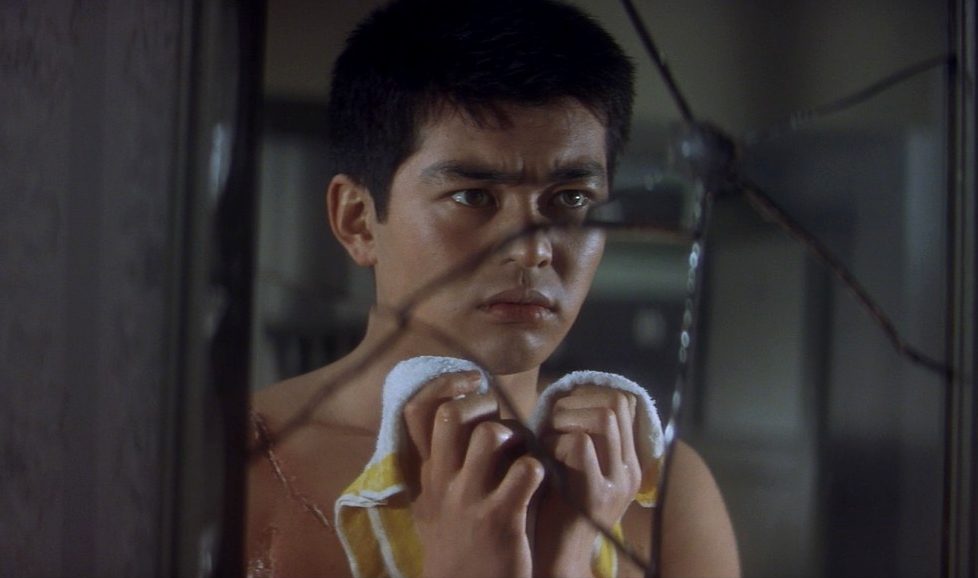

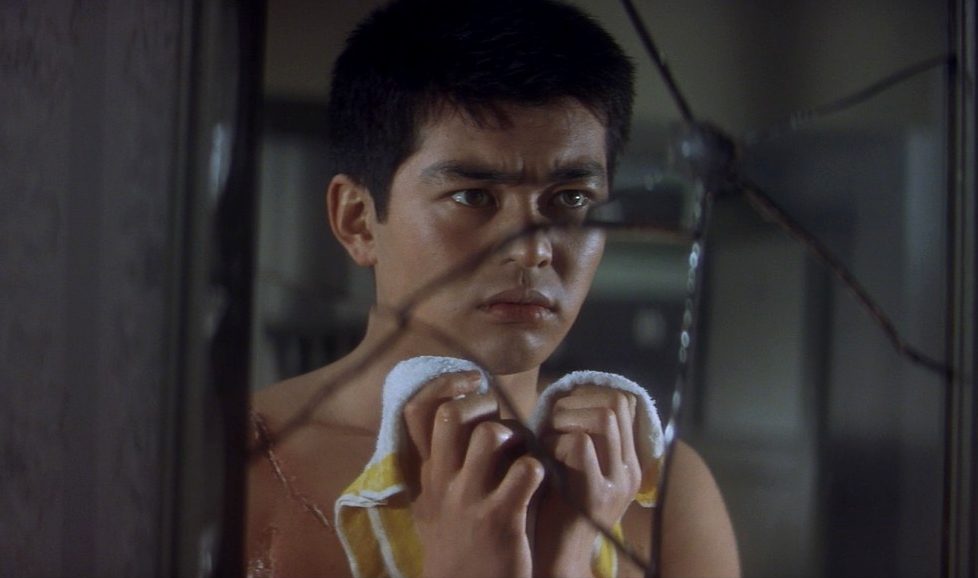

The rectilinear design of traditional Japanese homes offers plenty of opportunity for this, but Suzuki rarely misses a chance to shoot through bars, mesh, windows, doorways, even the floor! Or to use the walls of a set to divide the picture and draw the eye to the important parts. He also uses traditional triadic composition typical of classical Japanese woodblock prints—thought by some to be the origins of manga comics, which were also increasing in popularity in post-war Japan. Triadic composition achieves a sense of depth by placing figures or objects in the immediate foreground to emphasise the middle space between these and the more distant background.

This graphic influence is evident throughout and often the screen is broken down like the frames on a page. In the use of comic book aesthetics and its reinterpretation of the B Movie gangster genre, it reminds me of another colourful masterpiece of ‘60s super-cool: Mario Bava’s hugely enjoyable Danger: Diabolik (1968).

When Tokyo Drifter went into production at Nikkatsu, there wasn’t anything to suggest that it would be anything special. Still active today, the studios had a turbulent history since their founding in 1912, being one of just three Japanese studios to survive WWII. It rode out the war as a distribution company and didn’t return to film production until the mid-1950s after the construction of their new Chôfu studios as the cinema industry began to expand with an injection of investment.

The post-war years were the heyday of the B Movie. In a similar approach to the Hollywood studios model, Italy’s pulp cinema and, to some extent, Britain’s Hammer Films, they pushed out movies at quite a rate—averaging two per week at their peak. These films relied on a stable of writers, an ensemble of contracted talent with in-house technicians and directors. They exploited popular genres and, as Toho Studios seemed to have monopolised the daikaiju (a creature-feature genre typified by their Godzilla franchise), Nikkatsu went for mukokuseki akushun (crime-action potboilers often featuring Japanese yakuza gangs that paralleled Hollywood noir and Italian poliziotteschi).

As one of Nikkatsu’s contracted directors, Seijun Suzuki had already made dozens of films, many of which are now recognised as cult classics. He began to confidently assert his personal vision with the evocatively titled Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards! (1963), and started to garner a reputation as a problematic director who, increasingly, experimented with style and structure whilst disregarding the tried and tested formula. When he was assigned Tokyo Drifter, it came with a restrictively reduced budget, the studios expecting this to reign in his experimental flamboyance. It had the opposite effect!

The Japanese studio system was star-driven and the cast was more valuable than the crew. Tokyo Drifter was intended to create a new star in Tetsuya Watari, who’d recently signed with Nikkatsu. (It worked, Watari’s still a star in Japan and has made more than 100 films since.) It was written as a ‘pop-song’ film; a sort of extended promotional video intended to market a hit that rockets the singer to overnight stardom.

Watari plays Tetsu ‘the Phoenix’, an ex-yakuza assassin whose boss, Kurata (Ryûji Kita), has decided to give up crime and deal in legit real estate. One of the operations is a nightclub where Tetsu’s girlfriend Chiharu (Chieko Matsubara) sings torch songs—well just the one song it seems, “Tokyo Drifter”, written by Hajime Kaburagi who’d already composed music for more than 60 films and would go on to write another 160 in a career spanning 50 years. Tetsu also sings and whistles the song at various key moments in the film and Suzuki said he liked how it reminded him of the musically inclined heroes of classic westerns. The Paleface (1947) or Johnny Guitar (1954), perhaps?

Cinematographer Shigeyoshi Mine shot the opening sequence using spoilt monochrome stock. This made the start seem overly serious, almost expressionistic. It also features suited heavies walking toward the camera in a row—Tarantino did say this was a favourite, right? There’s a prolonged beating during which there’s the first hint we’re in for something a little bit weird and wonderful as the action is intercut with a hip figure in a yellow jacket shooting off-screen in various directions against a black background. When the recipient of the beating staggers off among the rolling stock of a rail yard he looks down to see a broken plastic gun at his feet. It’s the only thing in colour and it’s bright 1960s orange…

It turns out that it’s not so simple to walk away from a life of violent crime, and rival boss Otsuka (Eimei Esumi) is pressurising Tetsu to join his gang. When Tetsu flat refuses, Otsuka decides he’d be too big a risk to have around as a free agent, partly because if he ever turned evidence, he could sink both gangs, and partly because Otsuka intends to muscle-in on Kurata’s legit business. He knows that Tetsu’s sense of duty to his old boss would be a problem. So, Tetsu leaves Tokyo to live the life of a drifter until it all blows over. Not happy with that outcome, Otsuka sends his best assassin, Tatsu ‘the Viper’ to track down and neutralise Tetsu ‘the Phoenix’.

Here the story veers away from the yakuza genre and starts to feel more like a modern western, especially with the introduction of a third rogue assassin, Kenji ‘Shooting Star’, who steps in to help his old rival, Tetsu. We pretty much have a three-gun setup like The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), which itself had drawn inspiration from Japanese samurai films…

Just like in spaghetti westerns, there are some beautifully staged shoot-outs. One memorable scene against a backdrop of snow involves a showdown on a railway track with an approaching train in the background. Tetsu must calculate the speed of the train, the range of his pistol and how fast he can run. We see through his eyes as he counts the railway sleepers, the one marking the mutual range of his and his adversary’s pistols has been painted red for us.

The only scene that really doesn’t gel is a sort of slapstick bar brawl in which drunken Japanese hoodlums take on some GIs in a Western-themed saloon. It’s exuberant and included for two reasons: as light relief, we get to see three of the protagonists having a laugh together, and as a sort of big neon sign to point out the central subtext. Post-war Japan was having an identity crisis. On one hand, there’s so much heritage to be proud of, yet the old way of life led to a war with a very bad outcome and the influence of western culture was growing. They were now a protectorate of the US, which meant their military budget was freed up for regeneration through commerce.

Seijun Suzuki isn’t on a soapbox with Tokyo Drifter but it’s considering how the traditional culture was being swept aside by imported western values. The script reflects this with the new, younger gangs breaking old agreements to turn a profit and declaring quite openly that money and power are all that matter now. Although it never really becomes deeply philosophical, much of the dialogue between the rogue assassins is addressing the potential goods and evils of duty and honour.

The plot has often been criticised for not making sense and playing second fiddle to the cool style and clever set-pieces. Before viewing this version, I’d be inclined to agree, but this time through, the story seemed to make perfect sense. True it never gets bogged down with joining the dots in real time and we do tend to skip along to the interesting bits. Isn’t that a strong point and something a lot of other filmmakers could learn here?

In Seijun Suzuki’s own words, “viewers don’t care about anything except if the film’s interesting or boring.” Tokyo Drifter is never boring. The brand-new subtitle translation certainly helped it work even better. This time around, the story’s solidly constructed and told very clearly, albeit with what was such a cool narrative style it’s remained fresh to this day… Sadly, though, at the expense of the line “Don’t get familiar!”

director: Seijun Suzuki.

writer: Yasunori Kawauchi.

starring: Tetsuya Watari, Chieko Matsubara, Hideaki Nitani, Tamio Kawaji.