TO DIE FOR (1995)

A beautiful but naïve aspiring television personality films a documentary on teenagers with a darker ulterior motive.

A beautiful but naïve aspiring television personality films a documentary on teenagers with a darker ulterior motive.

‘Don’t stick your dick in crazy’ was popular 1990s advice. And in a question of life imitating art or vice versa, Hollywood was blowing up with tales of wild women demonstrating how dangerous the ‘weaker sex’ could be.

Fatal Attraction (1987) grossed an incredible $320M and earned six Academy Award nominations. Female-led suspense films such as Basic Instinct, Single White Female, and The Hand that Rocks the Cradle dominated popular culture—and those were just from 1992! While actresses explored a whole new range of dramatic roles, characters themselves would all pay the price for their hubris.

Dick-sticking panic may have sprouted from the mainstream news chasing the new media obsession of ‘crazy’ women. 24/7 coverage began with Aileen Wournos murdering seven men at the start of the decade and her six death sentence story of rape and revenge spanned over 10 years. Lorena Bobbitt ignited water-cooler gossip in 1993 when, following years of alleged abuse, she severed her husband’s penis and threw it out of her car window. Tonya Harding is banned for life by the US Figure Skating Association after conspiring to smash the leg of rival Nancy Kerrigan to prevent her from competing in the 1994 Winter Olympics. And then there’s an inspiration for this movie, Pamela Smart, but more on her later…

To Die For is a black comedy following Suzanne Stone (Nicole Kidman), a beautiful woman in small-town America, marrying young and spending time with the in-laws in a new house. A typical family spending their time in front of the television, Suzanne grows obsessed with aspirations of world renown on the screen and goes to extreme lengths to escape her suburban purgatory.

Gus Van Sant mirrors Suzanne’s obsession by interjecting the film with talking head segments offering grim foreshadowing, contrasting with the pastel story of their white-picket early romance. Jumping right into the midst of a developing story as if following it on the news ourselves we quickly learn that husband Larry Moretto (Matt Dillon) is dead and Suzanne is being taken in as the lead suspect.

The retelling of her story is hilariously conflicted as Janice (Illeana Douglas) tearfully regrets not pushing harder against her brother’s meet-cute while Suzanne cheerfully explains that marrying an Italian is her “exploring ethnic relationships as a future member of the professional media”. Sant plays off the news’ dramatisation of real events as people speak on behalf of the dead; a battle of perspectives and opinions when hard evidence isn’t enough to tell the full story.

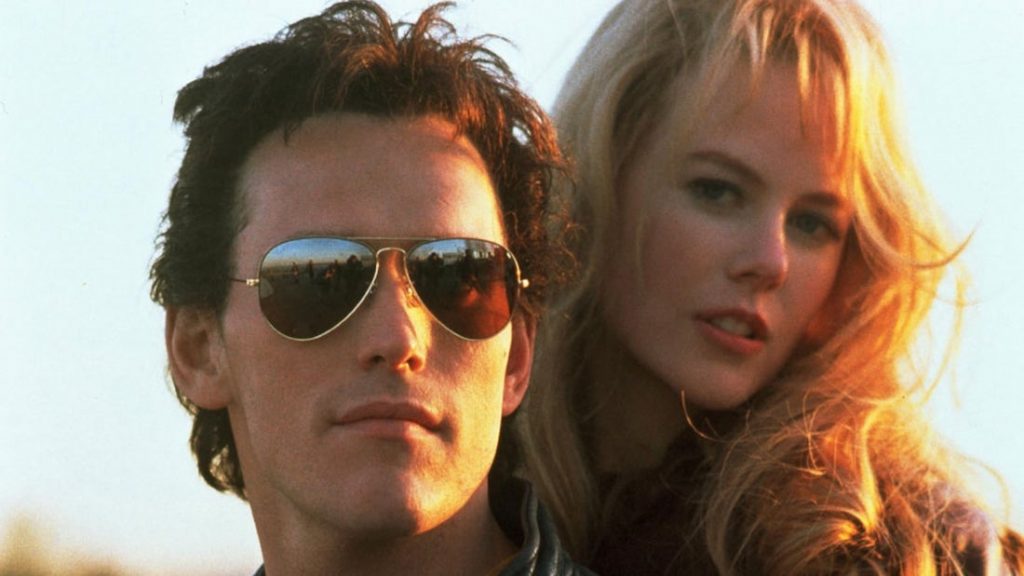

Like similar turbulent romances in Wild at Heart (1990) and Natural Born Killers (1994), Suzanne and Larry’s spontaneous lust-and-love story is an ominous Romeo and Juliet tale amplified by an aggressive hard rock soundtrack. Sant found great success in the queer cinema scene and To Die For critiques traditional heterosexual expectations in the media, becoming his subversive break into mainstream Hollywood.

Written by Buck Henry (The Graduate, What’s Up, Doc? Heaven Can Wait) and adapting the 1992 novel by Joyce Maynard, the film expertly expresses the obsessive psychoanalysing that news coverage became in it’s growing saturation. We don’t just want the facts of what happened but to discover exactly why she acted this way. Everyone has an opinion on Suzanne, not least of all herself, but the elusive inner workings of someone can never be understood as simple facts—although scientific journals have since diagnosed her with a severe narcissistic personality disorder.

“She’s like one of those porcelain figurines, you want to take care of her for the rest of your life,” remarks Larry in misguided admiration. It’s a perception of most women in Hollywood in which stars, like Kidman, were eager to escape. Developing compelling new characters rather than to be known as the wife of Tom Cruise and play love interests in glamourous Hollywood fare like Days of Thunder (1990), Far and Away (1992), and Batman Forever (1995).

People like Suzanne need no taking care of. Her eccentric determination takes her to lecherous news anchors offering advice on sexual favours (she dutifully downs her drink as we’re left to wonder if she committed) and wearing down the beleaguered manager of a local news station to try her as the weather broadcaster (when all they asked for was a secretary to fetch lunch). During her rise to success, we’re treated to many examples of her all-too-accurate understanding of the desperation of shallow content to fill the air time with anything remotely newsworthy. At one point she asks if they got “the memo on that children’s show with [her] as the hostess and live-studio animals!”

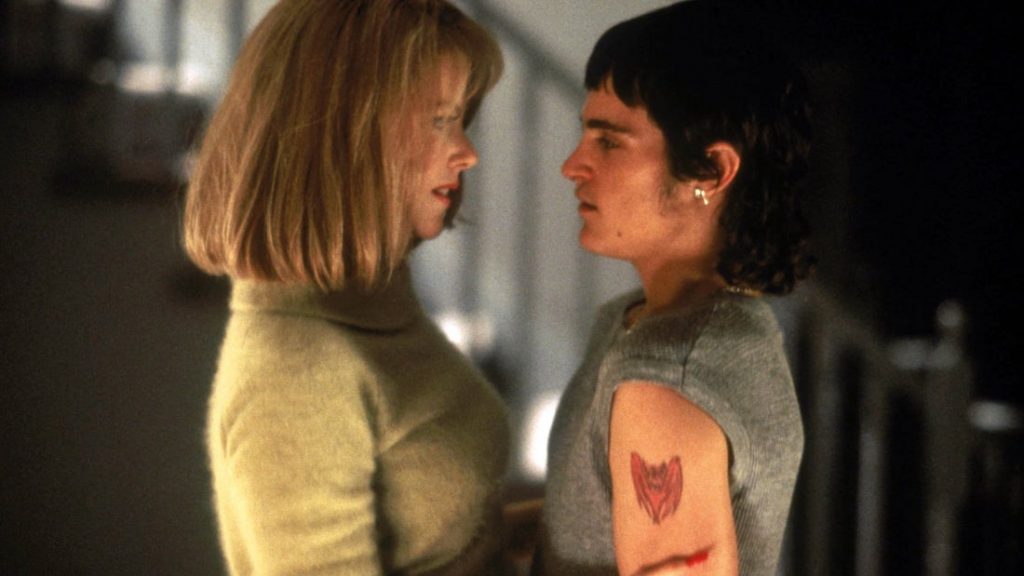

So who is the aforementioned Pamela Smart? In 1990, Smart’s husband Greggory was murdered by 15-year-old Billy Flynn and his three friends. An investigation was shared with the American public as the bizarre conspiracy of murder and manipulation revealed that 22-year-old Pamela was using underage sex with Billy to coerce him into an act he believed was freeing her from a troubled marriage. The analogous teenagers in To Die For are Jimmy (Joaquin Phoenix), Russell (Casey Affleck), and Liddy (Alison Folland); total opposites to the ambitious Suzanne, these three delinquents are anarchistic burnouts who spend their time smashing cars at the junkyard.

Joaquin’s introduction is fantastic. “Any time it rains, or when there’s thunder and lightning, or when it snows, I have to jack off”, is a shockingly blunt line but demonstrates the absolute hypnotic spell placed over him. He’s spurred into action when Suzanne suggests a real man like Russell could kill for her, who’s even more of a neanderthal than him. Meanwhile, the non-feminine Liddy feels instantly comfortable with Suzanne and is alluded as potentially lesbian though she’s really in need of any female friendship. Blatantly insincere, they nevertheless each fall for any hint of interest shown by an adult and like the grown-ups on TV they take her authority figure as gospel.

The second act follows their burgeoning friendship until an incredibly uncomfortable seduction sequence (with Liddy in the house, no less) and the assignment of cold-blooded murder. A wonderful moment of cinematography when Jimmy commits the crime while transfixed by Suzanne live on TV, removed from any sense of culpability but still looking on to make sure it happens.

The separation between screens is what connects everyone. Suzanne wants to be known everyone through broadcasting; believing in an intrinsic power that media shows people who they really are. It’s why she becomes fascinated in her personal project of recording hundreds of hours of interviewing today’s youth; unedited raw footage of messy, complicated lives and yet presented through a screen becomes something else.

Suzanne teaches us that “you’re not anybody in America unless you’re on TV […] if people are watching it makes you a better person”. She wishes to escape her humdrum marriage because these people content to just watch aren’t ‘people’. She seeks identity only found in a performance on-screen. When the grieving parents are sat in front of their TV playing the once standard national sign-off; Suzanne is drawn outside by the wave of news cameras all while the national anthem scores her ascension.

Pamela Smart is not like Suzanne Stone. Her story gained considerable attention as the first US. trial to allow cameras inside the court, but she has since resisted the spotlight. She argues that her conviction came not just from the institution but the audience transforming her into the movie monster that would become Suzanne.

For all those ‘crazy’ women in the ’90s, they were granted freedoms of equality by the second wave of feminism and aggressively liberated by the third wave. But it’s the now emerging fourth wave that seems to be critically addressing their plight. Second wavers sought to stop derogatory terms but third wavers reclaimed them, as Amy Dunne declared “I’m the cunt you married”. We’ve seen a lot of women explore the freedom of being a cunt and now with the likes of Monster (2003), the docuseries Lorena, and I, Tonya (2017), we’re breaking through those blanket representations of gender and mental health. Each person has their own incredible, strange, and sometimes morally questionable tales and yet even with 24/7 media, we’ll never truly know that crazy bitch.

USA • UK • CANADA | 1995 | 106 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Gus Van Sant.

writer: Buck Henry (based on the novel by Joyce Maynard).

starring: Nicole Kidman, Joaquin Phoenix, Matt Dillon, Casey Affleck, Illeana Douglas, Alison Folland, Dan Hedaya, Maria Tucci, Wayne Knight, Kurtwood Smith & Holland Taylor.