CARRIE (1976)

A shy teenage girl, sheltered by her religious mother, unleashes her telekinetic powers after being humiliated by her classmates at her senior prom.

A shy teenage girl, sheltered by her religious mother, unleashes her telekinetic powers after being humiliated by her classmates at her senior prom.

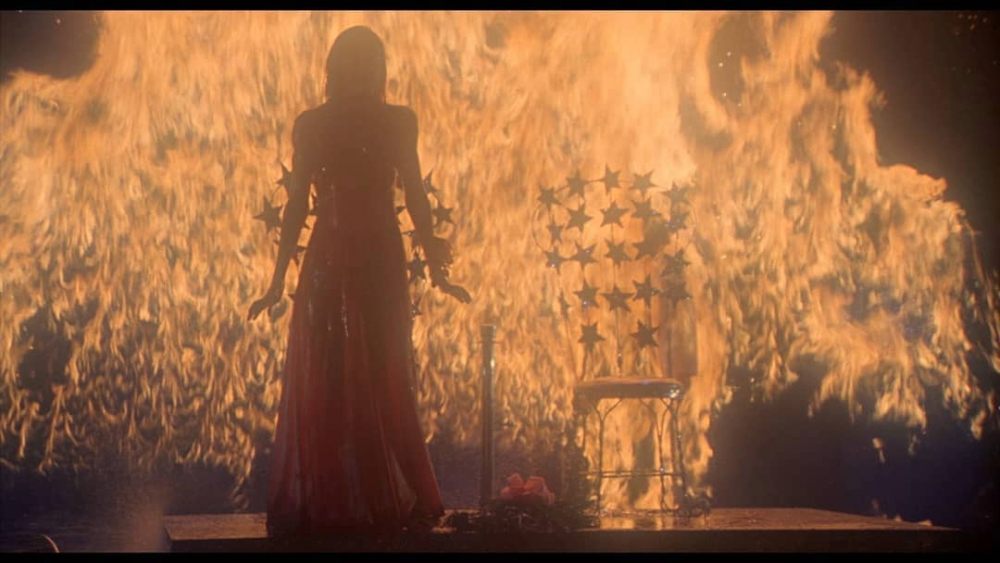

Brian De Palma’s Carrie is primarily famous for two things: the moment in its climactic scene where the eponymous Carrie White (Sissy Spacek) is drenched in pig’s blood at a high school prom, and its role as the first screen adaptation of a Stephen King novel. It remains one of the best, and what’s not so often realised is the part the movie played in propelling King himself to bestsellerdom. Indeed, the author was so comparatively little known before Carrie that his name was misspelt in a trailer.

It’s so much more than that. Most notably, the film can be seen as a “demon child” movie (the title character even toasts the devil at one point, albeit lightheartedly) where the demon child is sympathetic, and the story is largely told from her perspective. Carrie and her menstrual blood are, as far as filmic bodily substances go, as legendary as Regan (Linda Blair) and her vomit in William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973). Carrie is also responsible for more death and destruction than Regan. However, unlike Regan, she’s only a figure of terror very briefly, if at all.

Carrie is unusually notable for a horror film of the period, also due to some of its performances. Though Sissy Spacek had already made an impression in Terrence Malick’s Badlands (1973) and had major roles in a couple of other, less-remembered films today, it’s surely Carrie with which the young Spacek is most associated. The film was also a career highlight for Piper Laurie, who plays Carrie’s mother. Both actresses received Academy Award nominations, an extreme rarity for performers in horror films, then and now.

It’s also one of De Palma’s most effective films, regularly appearing at or near the top of his filmography when ranked alongside others like Carlito’s Way (1993) and Blow Out (1981). A quintessential De Palma movie, it bears much resemblance to his others. Though he’s made little out-and-out horror, of which Carrie was the first, much of his work is quite dark. Yet, the need for narrative restraint until the very end and the mostly teenage characters helped to restrain some of the excesses of violence and sexualisation that can afflict his movies.

Carrie is still a flamboyant film in style, but its scope is small-scale. It was adapted by Lawrence D. Cohen (with some uncredited first-draft writing by producer Paul Monash) from a novel that began as a short story. The storyline was so slight that King felt the need to flesh it out with quotations from fictional books, excerpts from supposed evidence given to a government inquiry, and so on.

Carrie White is an unpopular 16-year-old high school student who attracts the ridicule and revulsion of other girls when she has her first period in the school shower and doesn’t understand what is happening. A teacher, Miss Collins (Betty Buckley), takes her side and punishes her tormentors, but Carrie’s fiercely religious mother Margaret (Laurie) believes her daughter’s menstruation (like virtually everything else in her worldview) is the product of sin.

Angered by the punishment they believe Carrie brought upon them, a small group of contemporaries led by Chris (Nancy Allen) and her boyfriend, Billy (John Travolta), concoct a plan to humiliate her at the prom. Carrie, however, longs for acceptance by her peers and sees the prom as a chance to finally achieve it. Struggling with her mother for permission to attend, Carrie eventually resorts to her telekinetic powers, which she barely understands, to assert her dominance.

At the prom, Chris and Billy execute their cruel plan, despite a last-minute attempt by Chris’s classmate, Sue (Amy Irving), to thwart it. This emotional blow unleashes Carrie’s telekinesis to a far greater extent than ever before.

In most respects, this storyline follows King’s very closely, although there are some minor departures. The movie is set in California, rather than King’s usual setting of Maine. Miss Collins’s name has been changed, and so on. The novel also features more spectacular destruction at its climax and omits the rather gimmicky jump-scare ending of the film.

King’s novel also employs a technique of repeatedly inserting supposedly “objective” accounts. This technique achieves a dual purpose: it lends credibility to the story while simultaneously distancing the reader from the events described. As a result, the story of Carrie feels like something that happened to other people in another place at another time.

While the 2013 remake and the 2002 TV version employ King’s tactic (to a very limited extent), De Palma’s film eschews it entirely. The result is a movie that’s much wilder and more emotional than the more factually grounded novel. The novel’s structure also allows for a much richer backstory, which makes the destruction of the White family home in the film’s climax appear to come out of nowhere.

An already fairly forthright and unambiguous book became, in De Palma’s hands, a story with virtually no subtlety. What little subtlety remains exists in the character of Carrie herself (and Spacek’s performance) and her plight. Other potential nuances, such as Billy’s outsider status or Chris’s surely troubled psychology, are only suggested.

A few interesting ideas are hinted at here, certainly, reminding us that events can appear different depending on the perspective from which they’re viewed. Chris is slapped by both her teacher and her boyfriend (and while we might object to the teacher’s action in real life, it seems understandable within the film’s context, but the boyfriend’s slap is abusive. And Tommy (William Katt) “lies” by plagiarizing a poem for English class. We might even admire his audacity here. However, the rigging of the prom queen vote is a despicable act of deception.

Even though Sue and Tommy will emerge as relatively sympathetic fellow students, and the adults are at worst oblivious rather than actively malicious toward Carrie’s plight, the emphasis from the opening volleyball game is firmly on Carrie versus the world. Her physical positioning, separate from the rest of the group, makes this clear.

The irony of the famous locker-room sequence that follows is that it depicts Carrie, metaphorically, finally becoming more like her schoolmates with her belated first period. Indeed, this sets up an important point in the movie that’s easy to overlook amid Carrie’s climactic fury: she desires normalcy, to be like them. The importance they (and perhaps less consciously, Carrie herself) place on sexuality in their definition of “normal” is reflected in De Palma’s visual handling of this section. This section also, of course, satirises the presumed male audience’s perspective on naked young women. With its slow-motion, soft-focus presentation of Carrie, half-visible in the steam from the showers, then dreamily soaping her breasts, it’s unmistakably intended to evoke pornography.

He used a strikingly similar approach in the opening shower scene of his film Dressed to Kill (1989). In fact, Sisters (1972), which predates Carrie, also opens with what appears to be an outrageous male gaze fantasy unfolding in a locker room, only to be revealed as a game show set-up. Critic Sean Burns aptly sums up the director’s attitude: “De Palma was smart about being sleazy, always up for using gratuitous nudity as self-aware commentary on female objectification and the male gaze, while at the same time revelling in the trashy pleasures therein.”

Furthermore, as the insightful supplement Visualizing Carrie included with Arrow Video’s disc astutely observes, the abnormally early nudity in the film also unsettles viewers. De Palma then builds upon this unease with a shocking jolt: the sudden appearance of blood. (Many viewers who first saw Carrie would not have been familiar with the novel.) He quickly piles on further signs of the film’s direction: the girls’ jeering at Carrie, the ashtray trembling on the high school principal’s desk when she’s called in to see him (foreshadowing her telekinesis, though unexplained at this point), and a similar scene with her brown-bag lunch quivering on her school desk. Carrie’s insistence on the correct pronunciation of her name when she’s with the principal also highlights another element that, alongside her unusual abilities and outcast status at school, will culminate in the film’s climax: her strong will.

Brian De Palma is quite open about seeing himself as a Hitchcockian director, and, like Alfred Hitchcock, he is often viewed as misogynistic. The accusation isn’t entirely without foundation, although this attitude doesn’t dominate his films to the degree sometimes implied. Moreover, the portrayal of women in his films was far less exceptional in the 1970s and 1980s than it is today.

In any case, it’s difficult to see Carrie in this light; the shower sequence satirises the male gaze rather than indulging it (especially since the only gazes depicted in the film’s reality are female). Additionally, no male character in the film is nearly as significant as the four main female characters—Carrie herself, her mother, Sue, Chris, and Miss Collins.

What is undeniably characteristic of De Palma’s work in Carrie is its frequently stylised and mannered approach, evident both visually and in the construction of individual scenes and sequences. It’s fair to say that he prioritises creating striking effects over achieving a wholly believable depiction of characters and events. This is apparent throughout Carrie, where almost everything is presented in a slightly (or perhaps more than slightly) exaggerated manner.

The film occasionally veers close to self-parody. This is evident in the ominous statuette of St. Sebastian in the cupboard where Carrie’s mother locks her, the lightning dramatically illuminating her mother at the dinner table, and the ludicrously overwrought death scene involving kitchen utensils near the end. At other times, the exaggeration is less obvious but still present. The vivid colours of the students’ clothing in the gym roll call scene, the mannerisms of the English teacher (Sydney Lassick), and the janitor cleaning Carrie-related graffiti off the wall—all these elements are just a touch larger than life.

Other moments are larger than life, most notably Carrie’s ascension to the stage as prom queen (aided by Pino Donaggio’s score, the rapturous glances exchanged by a couple of teachers, and a close-up of Carrie’s eye). As is often the case with De Palma, colours are used as unifying leitmotifs. While he’s frequently associated with white, in Carrie it’s the heavy use of red that lingers in the memory. The diegetic lighting of the prom is itself very artificial and stylised—as you’d expect from a movie set in the ’70s—and De Palma then takes this into completely non-naturalistic territory.

His touch isn’t always assured. He regretted the overuse of split-screen, which lessened the impact of the climax by reminding us we’re simply watching a film (though this didn’t put him off split-screen in general). The split dioptre technique, which allows the camera to focus on objects in two different planes at the same time, is far more subtle and enhances the effectiveness of individual scenes without being immediately noticeable to the viewer.

In a humorous attempt to add variety and briefly lessen the film’s emotional intensity, De Palma employs a scene where the boys choose their tuxedos for the prom. However, this sequence feels out of place and draws unnecessary attention to itself. Similarly, the almost comical skulking around the prom accompanied by cartoonish music, before the reveal of a bucket suspended high in the building’s structure, feels jarring.

Tommy’s fate, meanwhile, certainly seems like a cop-out, avoiding the question of whether Carrie’s wrath would extend to him. However, in fairness to the filmmakers, it is directly lifted from King’s source material.

More controversially, the final dream scene, said to be inspired by John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972), doesn’t work for me either. While many viewers, including King himself, like it (although it was De Palma’s idea and he would reuse it differently in Dressed to Kill), I find it ineffective. It’s cleverly put together, though… a ‘FOR SALE’ sign resembles a cemetery cross, and a character was filmed walking backwards—the film was then reversed to create a slightly unnatural feel to her forward walk.

However, it rather negates the tragedy of Carrie White’s fate. It seems to either hint at a malevolent supernatural element to her that the rest of the film doesn’t substantiate. Or, perhaps it’s simply saying that people who have bad experiences might have nightmares about them afterwards, which is hardly groundbreaking.

Like De Palma’s direction, the performances are mostly big and broad, rather than finely nuanced. This is often heightened by the way the actors are filmed too. For example, shooting Laurie’s Margaret White from below when she’s berating Carrie. Many of them are still strong performances, even if they are overshadowed by Spacek’s. And although (as usual) the cast is older than the teenage characters, this never becomes a problem. It’s such a convention that it’s easy to overlook.

Particularly noteworthy are Allen as Chris, full of high emotion, and Buckley as Miss Collins. The importance of the teacher’s role is often overlooked. Her heartfelt, yet more restrained, anger at Carrie’s bullying provides a counterpoint to the girl’s unfocused rage. Similarly, Chris’s unhappiness and victimisation (for instance, by her boyfriend) mirror Carrie’s experiences, albeit in a less extreme way. Allen later delivered another notable performance in Dressed to Kill.

Irving, as Sue, one of the few sympathetic students, isn’t entirely convincing, but that’s at least as much the fault of the script as the actor’s. Her motivations, or at least her thought processes, aren’t made clear enough.

Katt, as Tommy, is also rather bland—his only real role is to be nice. Similarly, Travolta as Billy doesn’t have much to do except play the bad boy. However, their reduction to semi-caricatures is surely intentional. They might also represent boys as girls (ostensibly) see them: the closest things to movie stars their high school offers. As Pauline Kale wrote, Katt “acts like a fantasy of [Robert] Redford at seventeen,” while Travolta “might be Warren Beatty’s lowlife younger brother.”

Carrie was cast at the same time as George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977), with actors attending a joint audition for both films. It’s fun to speculate how the films might have turned out if the casting had been slightly different. Spacek could have been a captivating Princess Leia, but she was so perfect for the role of Carrie that we should be grateful Carrie Fisher landed the Star Wars part instead. (In reality, Spacek was always destined for Carrie—her husband, Jack Fisk, was the production designer.)

King purists might argue that she’s too beautiful for the role (Carrie in the book is plain and frog-like). But Spacek—with the help of hair, makeup, costume, and cinematography—pulls off magnificently the transformation from a dowdy, unhappy girl downtrodden at both school and home, to the radiant prom queen. Her character may be withdrawn, but her acting isn’t; she based it partly on Gustave Doré’s dark, theatrical Biblical illustrations, and the New York film critic Dan Callahan rightly referred to the “silent movie extravagance” of her performance.

Carrie’s distress in the opening shower scene is palpable. Her simple line, “I love you, mama,” is deeply saddening. The long hair obscuring her face is a poignant expression of her isolation. There are some differences between Stephen King’s Carrie and the movie character. For instance, it’s made more explicit that King’s character enjoys revenge. Nevertheless, despite the novel and various subsequent screen productions, it was Spacek who defined the character in the public consciousness and continues to do so, nearly half a century later.

Donaggio’s music is far less memorable than the events it underscores, but it does offer some insight into De Palma’s conception of the film. Bernard Herrmann’s score for Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) was used for Carrie as a temp track (i.e. music not intended for the final film, but used during the editing process to give it a more cinematic feel and to suggest the overall tone of the final score.) The finished score by Donaggio—who had worked with Herrmann and would later score several other De Palma films including Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, and Body Double—pays direct homage to the famous shower-scene strings from Psycho. While otherwise unremarkable, if competent, the music is the most obvious of several connections between Carrie and the Hitchcock film.

Even though the shower’s pivotal role might be entirely coincidental (and of course originates with Hitchcock), other allusions are deliberate and come from the filmmakers. For example, the overhead shot of Carrie’s mother holding a knife mirrors one of Norman Bates’s mother. Likewise, the renaming of the school to Bates High School leaves no room for doubt! More broadly, the films are bound together by the theme of a young person being dominated by a cruel and mocking mother.

However, the fairness of these parallels—particularly the equation of Carrie with Norman Bates—is debatable. Norman is a psychologically and sexually tormented serial killer. While not entirely unsympathetic, he’s never portrayed as anything approaching “normal.” Carrie, on the other hand, would be perfectly normal for a teenager if not for her telekinetic powers. She’d gladly trade them for popularity at school. As is often the case with De Palma’s work, what appears to be a powerful idea on the surface might not hold up under closer scrutiny.

Carrie was well-received at the time and has maintained its reputation. When it came out, Pauline Kael called it “a perverse mixture of comedy and humour and tension” and particularly praised Spacek’s performance. Others have since been effusive in their praise—it’s “a pop masterpiece” according to Owen Gleiberman, “the primal school film… wildly lurid and funny” according to Kael’s New Yorker successor, David Denby, who perceptively compared it to Heathers (1988).

There have been three subsequent Carrie films—none of them entirely satisfying. (William Wyler’s 1952 Carrie of course predates King’s and has nothing to do with the franchise.) Katt Shea’s The Rage: Carrie 2 (1999) is packed with homages to the De Palma film, starting with red paint at the very beginning and even including some footage from the original. Unfortunately, the plot also tries too hard to mirror the first film, but ultimately falls short. The outsider status of the telekinetic girl (not Carrie White), played here by Emily Bergl, is unconvincing, and her “strict” parents can’t hold a candle to Laurie’s terrifying Margaret White. The climactic scene is also laughable; a few decent performances are countered by some truly awful ones. At least the ruins of the old high school provide a suitably atmospheric if somewhat implausible backdrop.

This was followed by a 2002 TV adaptation starring Angela Bettis as Carrie. Its dramatically different ending appeared to be intended as the starting point for a series that never came to fruition. Then came a remake, not a sequel, in the form of Kimberly Peirce’s Carrie (2013), starring Chloë Grace Moretz and the well-cast Julianne Moore as Margaret. While competent, it never quite captured the intensity or dread of the original.

More significant has been the wider influence of this 1976 film. Stephen King’s novel Firestarter has clear affinities with Carrie and has been filmed twice, in 1984 and 2022. Here, the influence may seem to lie solely with the literary source material. However, given the role of De Palma’s film in the novel’s success, it’s not a huge leap to see the Firestarter movies as indebted to it.

Beyond King’s work, De Palma explored similar ideas in The Fury (1978)—a girl even has a nosebleed at school, like Carrie!—and more recently we saw traces of Carrie in films like Brightburn (2019) and Eskil Vogt’s superb The Innocents / De Uskyldige (2021). The latter is particularly interesting for its portrayal of children with mysterious powers from their own perspective—exactly the same reversal employed in Carrie.

While subtlety might not be De Palma’s or King’s greatest strength in most of their work, this is one instance where understatement proves highly effective. Much of the film’s power (even more so than the novel’s) stems from adopting this unconventional perspective, but without labouring the point.

Undoubtedly, Carrie’s greatest strengths lie in aspects that aren’t necessarily the most famous. The prom scene, and its aftermath, are undeniably the most memorable parts of the film. However, the earlier sections, which resonate more with recognisable real life (albeit exaggerated), are often more successful. De Palma’s direction, particularly his use of split-screen towards the end, verges on becoming overly elaborate, which doesn’t help matters. Additionally, the element of surprise is absent for today’s audiences.

It’s perhaps unfair that the film is so strongly associated with its Grand Guignol elements, which make up a relatively small portion of its running time. As British writer Neil Mitchell suggests, “For De Palma, Carrie was a serious movie, with serious points to make about the cruelty of teenagers, the insidious effects of religious fervour, and the state of contemporary American society, regardless of it being wrapped up in supernatural trappings. United Artists, however, marketed Carrie as cheap popcorn entertainment.”

It’s superb popcorn entertainment, too. But strip away the wilder elements of the plot and storytelling, and there’s something more lurking beneath. In Carrie White’s character, we see a reflection of ourselves—child or adult—anyone who’s ever been cruelly ostracised by a group, simply for wanting to belong. And we’re forced to confront an uncomfortable truth: no matter how much sympathy we feel for the poor girl cowering in the shower, we too are capable of being part of the bullying crowd.

USA | 1976 | 98 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Brian De Palma.

writer: Lawrence D. Cohen (based on the novel by Stephen King).

starring: Sissy Spacek, Piper Laurie, Amy Irving, William Katt & John Travolta.