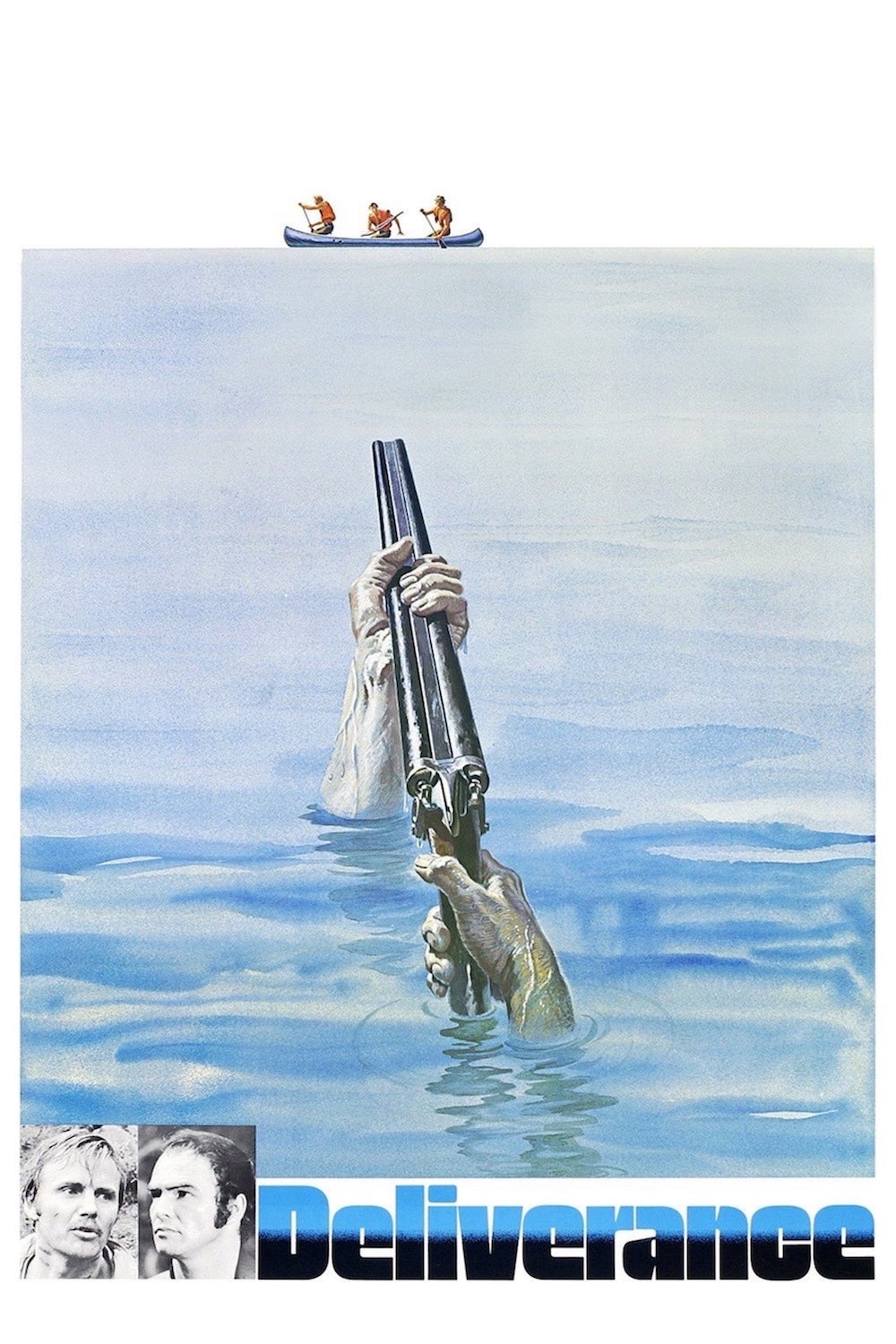

DELIVERANCE (1972)

Four city men on a wilderness canoeing trip face deadly threats from both nature and the locals.

Four city men on a wilderness canoeing trip face deadly threats from both nature and the locals.

Poet-turned-novelist James Dickey’s screenplay adaptation of his own novel, Deliverance, is mostly very faithful to his 1970 story, but the places where it differs are critically important—for better or worse—in creating the film’s atmosphere, and two of them are probably its best-remembered scenes.

First, the rape of Bobby (Ned Beatty) by a pair of mountain men in the backwoods of Georgia is more elaborately cruel in the movie than in the novel. The famous “squeal like a pig” line wasn’t written by Dickey but improvised on location, and its nightmarish quality contrasts with the devastatingly precise but dispassionate style of the author’s prose.

Second, the impromptu “Dueling Banjos” duet, performed by Drew (Ronny Cox) and a local boy (Billy Redden), has more ominous import in the film, presaging the conflicts that’ll erupt between the four city men visiting the Georgia wilderness and its locals. In the novel, both Drew and the boy Ronnie seem to be united in musical delight rather than competition; a point that’s important both in establishing the character of Drew and in underlining that Deliverance the novel doesn’t by any means portray every local as hostile. (Nor does the movie, to be fair, but its positive depictions tend to be forgotten.)

Perhaps the most important change of all, however, and the one that signifies the biggest difference with the film adaptation of Deliverance, is the cliff-climbing scene where Ed (Jon Voight) must force his way up the steep sides of a river gorge on a mission to kill the second of the two rapists. This scene—for which Voight actually performed the climb, director John Boorman having decided to save money by not hiring stuntmen—takes up around 5% of the book and is an intense, minutely observed sequence where the character’s struggle with the rock is a clear encapsulation of all four men’s struggle with the wilderness, and his triumph in eventually reaching the top is the moment where Ed finally becomes the purely physical, pre-civilised man that his idol Lewis (Burt Reynolds) has always claimed or aspired to be.

“The whole thing is going to be reduced to the human body, once and for all,” Lewis says in the novel. “The character of Lewis has a baleful fascination for the other kind of soft-jowled suburbanites that he leads into the expedition,” Dickey has commented. For Ed, that fascination is now a reality.

But in the movie, this sequence is less to the forefront, taking up less than 2% of the runtime, and the cliff feels like merely another obstacle to be overcome.

Deliverance the film, then, is more of an action thriller than its source material. Indeed, Dickey and Boorman argued over the director’s insistence on reducing a long early sequence in the screenplay showing the men back in the city (intended to heighten the contrast between their safe lives and their dangerous expedition), and to place the focus squarely on the way they change as individuals. Instead, the movie is less concerned with the men as people and more with what happens to them. It thus lacks most of the exposition on their backgrounds and personalities that the book provides.

The narrative is simple. Ed, Lewis, Bobby and Drew—all of them urbanites, although Lewis is fascinated by survivalism—set out on a short canoe trip in northern Georgia, hoping to experience the fictional Cahulawassee River before it’s drowned in a huge damming project. (The river was actually the Chattooga, which became a popular rafting destination after the success of Deliverance, and the site of several fatal accidents.)

Their initial encounters with sceptical locals are humiliating, as the men’s image of themselves as intrepid explorers isn’t shared by those who actually know the river. Bobby in particular seems physically and temperamentally unsuited to the trip. But all goes well, at first, until the four become split up and two of them meet the rapists.

Almost a trivial scene in terms of theme and character development, the rape is nevertheless pivotal for the rest of the film. One of the assailants is killed and divisions emerge among the four on whether to report the incident to the police or simply hide his body—a blatant choice between obeying the laws of civilisation or following the ways of nature, red in tooth and claw. Shortly afterwards, one of the four men is also apparently killed (it’s not clear quite how) and another is injured. So it falls to Ed to get to the top of the cliff and eliminate the remaining mountain man, who he and his surviving companions assume is trying to pick them off.

There are plot ambiguities. For example, is a character shot, or does he just fall out of a canoe? Does Ed eventually kill the right man? Were the mountain men planning the rape all along, or was it just happenstance that they stumbled across the visitors? But despite all the attention paid to these issues (inevitably) in discussion amongst fans, they don’t really matter to the experience of Deliverance. And indeed, the fact we don’t know with certainty everything that’s going on adds to the effect by putting us in the same boat (figuratively) as the four men. A question asked near the end by a sheriff (played by Dickey after he’d patched up his differences with Boorman) does provide the key to at least one of the “mysteries”, but they’re not the point.

What really matters are the relentless progress of the narrative, its onward push as ceaseless as the river’s, and Boorman’s direction. Like the novel, the film is largely matter-of-fact; as things get worse and worse for the four men there’s no substantial change in mood apart from more kinetic white-water scenes… but this is a strength rather than a failing, adding to the impression that their fate might have been preordained from the moment they stepped into the river.

And although David Thomson has argued that the movie “does not fully catch Dickey’s troubled apprehension of nature” (and there’s a little truth in this, for example in the way the cliff scene is downplayed), Boorman and his director of photography—the great Vilmos Zsigmond—nevertheless successfully convey the peril beneath the idyll. Despite the widescreen format and the use of arcing shots (becoming popular at the time), Deliverance is claustrophobic. The depth of the gorge is key to the story but isn’t depicted for a long time. We literally can’t see a way out; the four men are enclosed rather than liberated by the wilderness, and the colour scheme of green-brown and grey-blue suggests death, decay and unfeelingness more than the joys of nature. Even when Ed reaches the top of the cliff, there is no sense of escape; his surroundings exude hostility.

This creation of unease extends to the filming of the local characters, too. From the first time we meet them up to Ed’s climactic confrontation at the top of the cliff, they frequently make their appearance by drifting into the background of the frame, almost unnoticed. It’s as if the film draws no distinction between the threat of the environment and the threat of the humans within it.

The four city men, however, have the only large roles. They too are often diminished almost to nothingness by the sheer scale of the wilderness and the implacable nature of the dangers they are facing. But still, the performances of all four manage to create clearly distinct individuals and do much to make up for the elimination of most of their backstories.

Voight was the only one at all well-known on film—mostly for Midnight Cowboy (1969)—and the shift in emphasis from Reynolds’s Lewis to Voight’s quieter Ed is central to the movie. It’s Ed we come to identify with more than the rather domineering Lewis (Ed even narrates the novel), and the differences between them are made obvious physically by the actors as well as by the screenplay.

The most memorable of the leads, however, is Beatty’s Bobby: though primarily remembered as the unfortunate rape victim, he’s drawn with more complexity. He’s a boorish and insensitive man, albeit in a jolly way, and fond of his creature comforts. At first, he seems destined to be the weak link, but in fact he does master rowing. And in a late scene at a motel, we see how easily he gets on with strangers, more so than Ed. It’s Lewis who’s preoccupied with self-sufficiency but Bobby has strengths of his own.

Cox’s performance as Drew, meanwhile, is often forgotten, but again he harbours surprises. At first, he strikes the viewer as almost too straightforwardly good, to the point of weakness, but his own forcefulness emerges when he is arguing with Lewis about what to do with the mountain man’s body.

And again, it’s Ed who seems at a loss here. Deliverance is often much subtler than it appears on the surface: Ed’s acquisition of the kind of manliness that Lewis fetishises is certainly something that happens in the film, and the stage where his desire to go to the police and do the legally right thing is overtaken by a more elemental survival instinct is key. But it’s not put forward as the only virtue, by any means.

In the much smaller other roles, meanwhile, it’s Redden’s banjo-playing boy with his ageless face who sticks in most people’s minds. He stayed in the area after Deliverance was filmed rather than succumbing to the allure of showbiz, but did go on to play the instrument in several other movies.

It’s tempting, but almost certainly wrong, to reduce Deliverance to a single-idea movie. Is it a parable of America’s settlement, a warning about man’s inability to tame the wilderness (“wilderness” here including inbred hillbillies)? It might look like that superficially (“you don’t beat it”, Lewis says of the river), but the argument isn’t tenable; the city men do mostly make it through their ordeal in the end, and the river is dammed.

Is it a mythic tale of self-realisation, its four men discovering “inner selves” only discoverable through encountering nature? Perhaps to an extent, but if so it doesn’t put a simplistic value on one inner self over another. The men aren’t divided into winners and losers. What ultimately gives such an uncomplicated narrative such strength is that all these themes are present, but none dominate—they’re more powerful just hanging in the background—and nothing’s as clearcut as it first seems. The city men use “primitive” bows and arrows while it’s the rural men who use more “sophisticated” guns, for example.

Deliverance was a major box office hit (grossing $46M) on a rather small $2M budget (which makes it surprising there were no sequels or remakes), and it was generally applauded by critics, with a few dissenters. Pauline Kael, for example, thought it impressive but sterile, saying its “mannered, ghastly-lovely cumulative power” were offset by “the formality of a nightmare” and constant awareness of actors acting, criticism with some justification.

It received Academy Award nominations for ‘Best Picture’, ‘Best Director’, and ‘Best Film Editing’ (losing to The Godfather on the first and Cabaret on the others), it turned Burt Reynolds into a superstar, and made Georgia a favoured location for filmmakers.

It doesn’t have quite the impact of Dickey’s novel, however. With a 109-minute runtime, it can’t quite fully immerse us into the experience of being trapped on a river, and of every small thing being magnified and threatening. But it remains both a terrifically watchable movie—for much more than a few legendary scenes—and also a troubling one, questioning whether both civilisation and nature are everything we assume them to be, and resolutely refusing to answer that question.

USA | 1972 | 109 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: John Boorman.

writer: James Dickey (based on his novel).

starring: Jon Voight, Burt Reynolds, Ned Beatty & Ronny Cox.