THE LAST PICTURE SHOW (1971)

High school students in a sleepy Texas backwater must come to terms with life, love and loss

High school students in a sleepy Texas backwater must come to terms with life, love and loss

The first shot of The Last Picture Show gives us the Royal; an ageing, fleapit cinema in the dying Texas town of Anarene. The rise of television is one reason this picture house is on the way out in 1951, of course, but so is Anarene’s entire way of life. And while the film’s directly autobiographical for co-writer Larry McMurtry, on whose novel it’s based (he grew up in a similar town, and was born only a few years before the movie’s leads), the end of this cinema and all it stands for is clearly symbolic for writer-director Peter Bogdanovich too.

Bogdanovich, who died this week at the age of 82 and whose masterpiece The Last Picture Show is, had been a film journalist, film historian, and arthouse programmer before he turned to filmmaking himself, and much of his screen work has cinema as a backdrop if not a principal subject. His debut as writer-director, Targets (1968), features an elderly horror actor played by Boris Karloff as a central character, and has its extended climax at a drive-in theatre, complete with careful portrayals of the projection booth; What’s Up, Doc? (1972) recreates the screwball comedy genre of half a century earlier; Nickelodeon (1976) is set in the world of silent filmmaking.

Indeed, several movies are directly featured in The Last Picture Show. Its high-school characters watch Father of the Bride (1950) at the beginning and Red River (1948) at the end, a number of posters appear in-between, and the back row of the Royal is a valued refuge for making out too. More importantly, though, the cinema represents all the things that movies mean–fantasies, dreams, adventure—and the news of its closure seems to confirm that many of those will soon be shut off for young people growing up in this dead-end town.

The cinema’s owner, Sam (Ben Johnson in one of the film’s two Academy Award-winning performances)—himself once young, but now middle-aged and wiser but still stuck in Anarene—could be a role model for boys like Sonny (Timothy Bottoms) and Duane (Jeff Bridges). But he could also be a reminder of how potential for greater things might be squandered if they don’t move on while they can.

Film’s inherent capability of capturing the past permanently is intrinsic to The Last Picture Show, too. For a movie that is, on the surface, mostly about its characters looking forward to the rest of their lives, it feels much more like one preoccupied with memory.

The decision by Bogdanovich to shoot in black-and-white (as suggested to him by Orson Welles) undoubtedly contributes to this sense that the entire world of The Last Picture Show is now irretrievably behind us, and it’s difficult to imagine the movie being so poignant or haunting in Technicolor. Indeed, although it’s set far later than most westerns, The Last Picture Show has something in common with end-of-the-Old-West movies; the choice of Red River for the final show at the Royal is probably not accidental.

Bogdanovich starts with the Royal, then pans away across an empty street, finally ending up on Sonny in his truck. Even the engine seems to have given up the ghost. He’ll show us the same empty street often, blown with sand and dust, tumbleweed on one occasion. The absence of a score (the only music in The Last Picture Show is diegetic—country songs on the radio, etc.) adds to the bleakness and isolation. So does the simple, direct style of photography favoured by the director and his cinematographer Robert Surtees, a visual match to the uncomplicated language of McMurtry’s novel.

And the film will end at the Royal too, dissolving to the cinema after a final scene that is both heartbreaking and very tentatively optimistic—possibly the best scene in the entire movie, one where Sonny just might have started to understand what adulthood and responsibility and friendship really mean, and also one where another character who seemed virtually destroyed might just have found unexpected inner strength.

Released in the US toward the end of 1971, and then slowly appearing around the world during 1972, The Last Picture Show follows the lives of a group of teens in Anarene over a few months during their last year at high school.

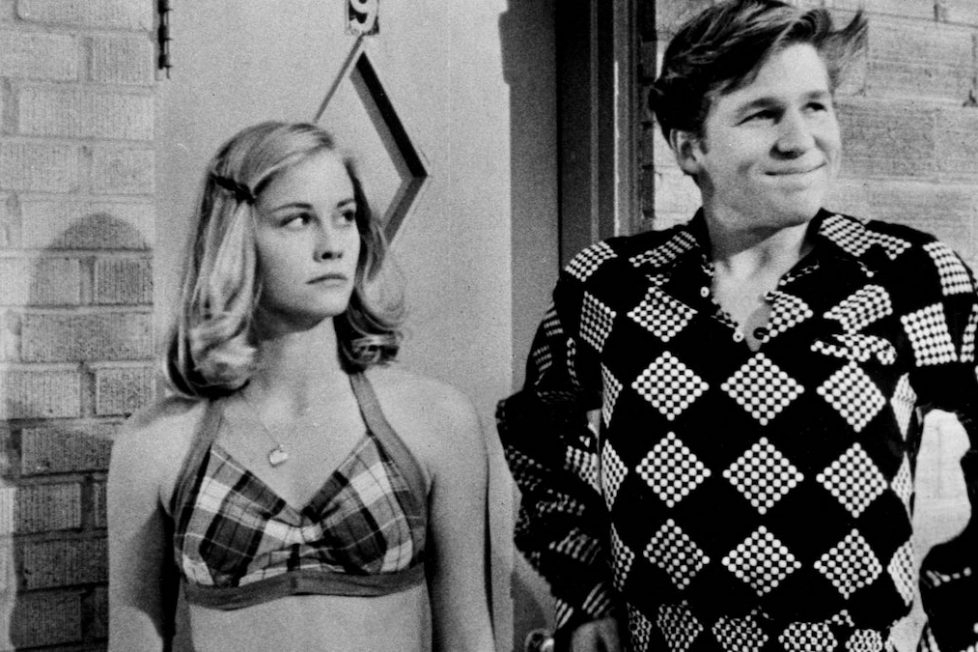

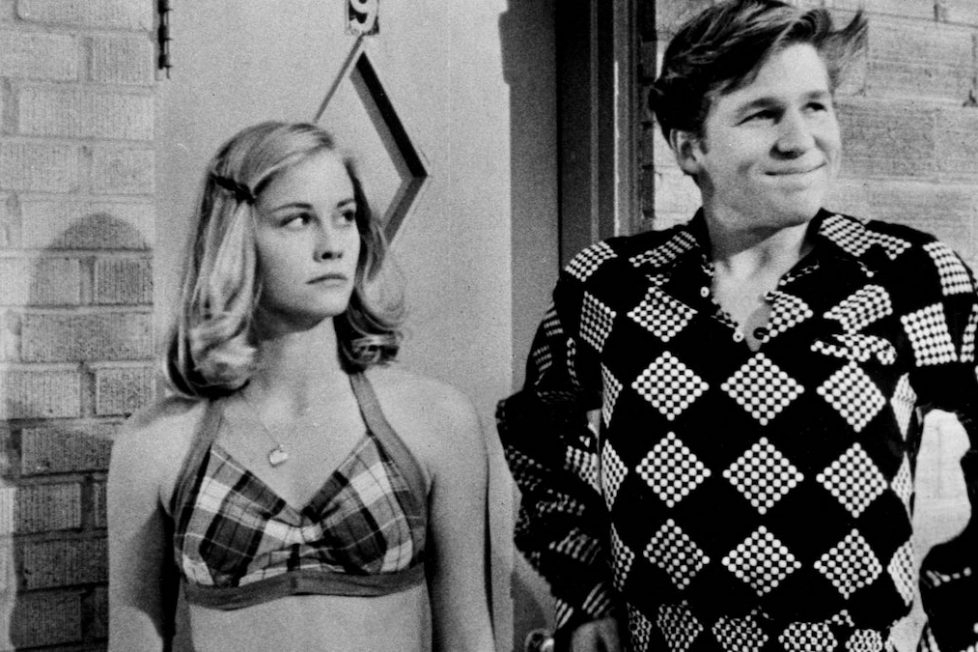

Salient among them are Sonny and Duane; also prominently featured are Jacy (Cybill Shepherd), seen as a prize by all the boys, Billy (Sam Bottoms)—a younger lad with learning difficulties—and Lester (Randy Quaid). As well as the teenagers, the film pays much attention to the adults with whom they interact, including Sam, who owns the pool hall and diner along with the cinema; Ruth (Cloris Leachman), lonely wife of the high school sports coach; Genevieve (Eileen Brennan), a waitress at the diner; and Lois (Ellen Burstyn), Jacy’s mother.

Many of the events it portrays are large to the teenagers even if they might seem trivial to the adults—who’s hooking up with who is inevitably a dominant question—but there are some genuinely big and tragic turns. Analene is “an awful small town for any kind of carrying-on, and some people got a lot of guns”, warns Genevieve, but in fact the dangers encountered by Sonny, Duane and their crowd are almost all emotional.

The plot seems to amble as aimlessly as the tumbleweed, but underneath it’s tightly constructed by Bogdanovich. Perhaps most notably, although The Last Picture Show looks at first glance like a teen movie, in reality the interactions between teens and adults are at least as important as those confined to the younger generation, possibly more so. Bogdanovich here underlines again how the film is as much concerned with memory and things past as with the present or the optimistically anticipated future.

The extreme and subtle care with which The Last Picture Show is constructed is evident, too, in the way that many scenes and even individual shots echo one another. Jacy pretends to be in love with Duane, and tells him she doesn’t want to go to a swim party with Lester, but in her face looking over Duane’s shoulder we can see the truth is the opposite; Ruth seems shy and nervous in an encounter with Sonny that’s critical to the story’s development, but in her face too calculation is visible.

Jacy gets to that swim party, where the ritual includes stripping on the diving board—a scene directed with a great sense of timing and humour, yet also with more serious intimations of the big and perhaps irrevocable step she’s taking away from Duane.

This is then mirrored in another of the film’s most famous scenes, where Sam recalls to Sonny how he skinny-dipped with another girl 20 years ago, and a key line here sums up a question repeatedly posed by The Last Picture Show: “being crazy ’bout a woman like her’s always the right thing to do. Bein’ a decrepit old bag of bones – that’s what’s ridiculous, gettin’ old…”

And this in turn is also echoed in a scene where Sonny and a woman undress. Again, there’s humour in the problems he has with taking off his boots, but for both of them, the act is also a possibly dangerous move into uncharted territory.

Sonny may learn an important life lesson here: however young and good-looking you might be, there is no way to remove socks while remaining cool, enigmatic and sexy. For The Last Picture Show, however, the significance of the scene is in the way that it thematically links apparently disparate incidents, as happens so often in this movie. (And there are other connections between the three cases I’ve mentioned here, though explaining them would risk spoiling.)

Besides the writing and Bogdanovich’s unostentatious direction, The Last Picture Show gains much from a terrific array of central performances, many of them by actors at the beginning of their careers who went on to be notable names. None are one-dimensional, none are overdone.

Bridges’s Duane and Bottoms’s Sonny are best friends but a study in opposites as well. Duane is straightforward and direct, perhaps not terribly bright, often positive in his outlook but changeable too, and crafty at times (alone among the group, he manages to avoid a stiff rebuke from Sam by hiding). Sonny is more intelligent, though certainly not academic, and more introspective; quite likely he will turn into Sam some years down the line.

Leachman is outstanding as the coach’s ignored and desperately sad wife; she “can’t seem to do anything without crying about it”, she says, and the aching need is visible in her face when we first see her kiss another man (a terrific brief scene). In a very different way, Burstyn excels as the much more confident mother Lois; her problem is not so much loneliness as boredom in this declining oil town where a visit to the Rig-Wam drive-in counts as excitement.

Jacy herself is perhaps taken a bit too far by Shepherd; this manipulative teen goddess is maybe too bad to be true. But she’s got great screen presence, as you’d expect from someone Genevieve describes as “the kind of girl that brings out meanness in men”. (Film critic Pauline Kael saw it slightly differently, considering Jacy “a projection of men’s resentment of the bitch-princesses they’re drawn to”.)

Brennan as Genevieve, for her part, balances Leachman and Burstyn with yet another kind of adult woman, one who seems to be happy in Anarene. Tolerant and perceptive, she is in many ways a female equivalent of Johnson’s Sam. In smaller roles, meanwhile, Barc Doyle as a preacher’s son and Sharon Ullrick as a girlfriend of Sonny’s are both amusing and affecting in their cameos, while Quaid’s Lester is memorable for his goofy grin.

The Last Picture Show was strongly applauded at the time, and was a big hit on a small budget (in the US it earned a lot more than the same year’s Shaft, for example, and wasn’t far behind A Clockwork Orange and Dirty Harry). Johnson and Leachman won Oscars; it was also nominated for ‘Best Picture’, ‘Best Direction’ and ‘Best Screenplay’, as well as for the performances of Burstyn and Bridges.

The film made Burstyn’s name, and Bridges was the biggest star to emerge from it. His performance is arguably better than Bottoms’, even if the latter’s character is more interesting. But for many others in The Last Picture Show’s cast it was also a major step forward.

Bogdanovich struck the right note with audiences again with What’s Up, Doc? (1972) and Paper Moon (1973), but then found it difficult to rebound from three successive failures in Daisy Miller (1974), At Long Last Love (1975) and Nickelodeon (1976), and is now best remembered for The Last Picture Show.

A Director’s Cut was released in 1992 (the most important addition being a scene where Jacy has sex with an older man and is then disappointed he won’t follow it up with affection, saying much about her real needs). The 1990 sequel Texasville—also written and directed by Bogdanovich, based on another of the five McMurtry novels set in The Last Picture Show’s world, and featuring many of its principal cast—wasn’t well received at the box office or critically, and is all but forgotten now.

The Last Picture Show, though, will not be forgotten. There are many films about growing up or growing old, or about loss, and many elegies to vanishing ways of life. What distinguishes Bogdanovich’s great movie is not what it has to say, but the utterly honest way in which it expresses that. As David Thomson wrote it is “a French film made in the West, with few illusions and no concession to romance”.

Not a thing in this film comes even close to being overstated, and that makes the emotional experiences of its characters—occasionally shouted about, but often unsaid—all the more powerful. Equally importantly, Bogdanovich and McMurtry never judge them (and there are certainly some bad things done in The Last Picture Show).

There may not be a “message”, but if there is one perhaps The Last Picture Show is almost making the case against nostalgia, and saying that—as Sam hints—it’s better to live in the now rather than gnawing at the past, or scheming for the future.

The last words of the movie go to Ruth, consoling another character, and she could well be making that point too. “Never you mind,” she says. “Never you mind.” This is life: worth it, whatever it throws at you, even in dusty Anarene.

USA | 1971 | 118 MINUTES • 126 MINUTES (DIRECTOR‘S CUT) | 1.85:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Peter Bogdanovich.

writers: Larry McMurtry & Peter Bogdanovich (based on the novel by Larry McMurtry).

starring: Timothy Bottoms, Jeff Bridges, Cybill Shepherd, Ben Johnson, Cloris Leachman, Ellen Burstyn & Randy Quaid.