MARRIAGE STORY (2019)

An incisive and compassionate look at a marriage breaking up and a family staying together.

An incisive and compassionate look at a marriage breaking up and a family staying together.

Marriage, or any long-term relationship, can have strange side-effects. One day you might look at your partner and be jolted into remembering they’re a separate person to you. Perhaps years of cohabiting and sharing everything (from what you dreamed about to toothbrushes) leads to this phenomenon; a jarring realisation that closeness doesn’t equal sameness, and that the person you share everything with can see you in ways that nobody else can… not even yourself.

Marriage Story is a film about this idea and the people who’ve so deeply merged with their partners, with the concept of marriage itself, that they no longer know who they are. It’s a film that poses the question ‘how do you love somebody when you no longer love what they represent in your life?’

Writer-director Noah Baumbach is no stranger to the inherent contradictions of human emotions. His previous film, The Meyerowitz Stories (2017), was an emotionally tortured look at the competitive and bitter dynamics of a fraying family, while The Squid and the Whale (2005) told a divorce story from the perspective of the troubled children. Marriage Story is possibly his most emotionally complex and moving film yet; the story of a couple going through the process of separation, then divorce. It’s a remarkably focussed work, staying almost entirely in the company of either theatre director husband Charlie Barber (Adam Driver) or his actress wife Nicole (Scarlett Johansson).

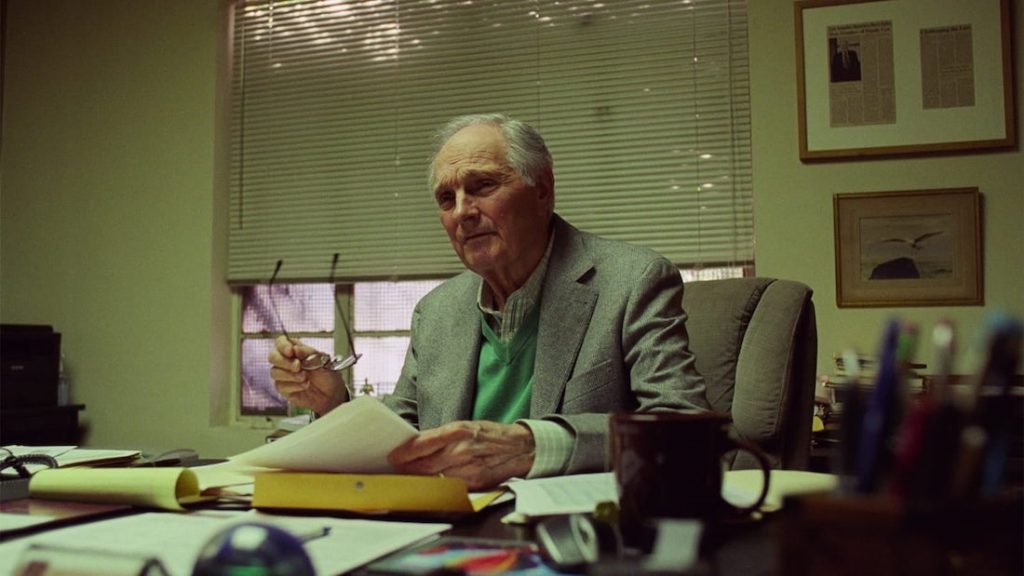

There’s an array of essential supporting characters, too—most notably a powerhouse Laura Dern and a deeply touching Alan Alda, as the Barbers’ respective divorce attorneys. But Charlie or Nicole appear in every scene. In a lesser film, this choice might become limiting, but the decision actually frees Baumbach up to dive into the mechanics of their dissolving relationship and explore their dynamic with specificity. Instead of complicating proceedings with needless subplots or contrivances, Baumbach instead ties every event in the film to the divorce, creating something so tangled and forceful that everything is viewed through the lens of Charlie and Nicole. However, while it’s unfolding, the film often feels light on its feet.

Baumbach opens the story, for example, with Charlie warmly describing the things that he loves about Nicole. Gorgeously grainy images of Nicole wandering down New York City streets (shot by cinematographer Robbie Ryan) play as he reminisces. Warmly lit scenes of domestic bliss (birthday gifts, games of Monopoly, dinners, and Sunday mornings) are so cosy and inviting they border on punchable, like an Instagram page of someone who loves their life a little too much. Randy Newman’s simple piano-based score gives it an air of throwback to something vintage, yet long-gone. The problem with the good old days is that they are old days.

While the film’s peppered with moments of earned and believable sweetness, the power lies in its sharp ability to weaponise these moments; to reappropriate them into something caustic and painful. In the opening, Nicole talks patiently with charity collectors—just another example of why Charlie loves her. Later, when a charity collector tells Charlie he looks like someone who wants to save the animals, he replies with a terse “nope” and marches straight on. When we hear Nicole describing the things she loves about Charlie, Baumbach shows us a moment from a family game night, where Charlie is endearingly passionate about the rules of the game. “He’s competitive”, Nicole reads. But we get this glimpse of the halcyon days before, supposedly, anything was wrong. We later find out that things were not okay, and now a moment of anger during a board game doesn’t feel as cute as it once did.

Baumbach masterfully makes us revisit and question everything we’ve seen. The good moments become bad, innocuous stuff becomes dangerous. As the separation drags on and as Nicole relocates with their son to Los Angeles to pursue an acting job, she and Charlie are slowly pitted against each other, aided by vicious lawyers who treat their clients like boxers before a fight. What was amicable becomes poisonous. Charlie insists they’re a New York family; Nicole’s lawyers say they’re an L.A family. The fractures become more severe as their perspectives shift, and as they gain independence from each other.

The film is ingeniously structured in a manner that lets the audience spend time on each side of the argument. The film’s first half is mostly spent with Nicole, the second primarily with Charlie. The kind of perspective this affords is much like ending a relationship: you’re finally seeing the other person for who they really are. And perhaps more daunting than that, you’re finally able to see who you are without the other. Alliances shift throughout, but Baumbach writes with a necessary nuance that vilifies neither. Real-life isn’t as simple as right and wrong, and, while the film points out their mistakes, it gestures to the idea that as glib as it might sound, sometimes these things just happen.

The film’s first half, focused on Nicole, eloquently lays out her side of things. When she first meets with her divorce lawyer Nora (Laura Dern), she tearfully unloads her reasoning for leaving Charlie, in words you can tell she’s been desperate to say for a long time. He overshadows her, makes every decision in their relationship and, most troublingly, doesn’t see her as her own person. The scene is Johansson’s best, played with the understated conversational manner of someone confessing sorrows to their best friend. She stops to praise the tea and cookies, moves around the office to grab tissues, and forcefully wipes away tears—they’re not cries for help, they’re hindrances. She wants to just get through this. Stopping to think is too hard, and she’s been doing that for too long. In this scene, Baumbach introduces the crucial third element to the marriage: other people and what they can gain from the couple.

Dern is fascinating as Nora. Seemingly warm and understanding, she initially resembles a therapist more than a lawyer. Yet the hints are there; she quietly plugs her book, and has an air of phoniness that suggests that she’s not really there for Nicole. It’s another job, and she knows how to work her client. Nicole may be an actress on the screen, but Nora is an actress in real life. There’s neat symmetry between characters here—Nora shamelessly hypes up her book, while Charlie repeatedly mentions that his last play has gone to Broadway. Nicole is surrounded by self-promotion and phoniness; it’s no wonder she’s desperate to define herself.

Meanwhile, Nicole’s mother, Sandra (Julie Hagerty), is overly attached to Charlie and treats him as her own son, only making things more difficult for Nicole. The scenes between Sandra, Nicole, and her sister Cassie (the dependably brilliant Merritt Wever) are some of the film’s funniest. Cassie and Sandra are so concerned about how they fit into Nicole’s marriage that they can’t get over themselves and do what Nicole asks. When Charlie comes to visit, Cassie is tasked with serving the divorce papers to him, in a scene that perfectly spirals into a borderline farce. That the two are still joking right up until the moment Charlie holds the papers in his hand is hilariously cruel—and an example of ow what a grip this film has on tone.

It’s the funniest moment of Marriage Story but it isn’t just comic relief. It represents the idea that, from a distance, the entire process of marriage and divorces is utterly absurd. It’s such a self-inflicted and convoluted process that it may as well be a scene from a broad comedy. And without missing a beat, the humour of it all is drained, as Nicole and Charlie talk without emotion about the next steps of divorce. It’s suddenly a procedural thing, not an emotional one. The entire scene could very well be a microcosm for the movie as a whole.

It also points towards the way these characters will interact from now on: rarely, and only when something practical needs to be worked out. Charlie picks up Henry from Nicole, and drives over to fix their gate. Nicole cuts Charlie’s hair. Sometimes they meet in lawyer’s offices. The scenes between them are icy on the surface but swelling with unspoken anger and grief underneath. They chart two people slipping away from each other’s orbit, facing into their own corners of the world. You can feel the ground rumbling before the mid-film climax, and its most praised and famous scene.

The fight between Charlie and Nicole is the final round in a battle that has lasted years, a final desperate hurtling of words in a deep need to hurt the other and to preserve themselves. It’s a riveting scene, as horrendous as it is cathartic. It feels like a blister finally being lanced, but nothing good comes out of it. The only positive thing is that the blister isn’t there any more. Driver, who is arguably one of the finest actors working today, plays Charlie’s whiplash emotions in this scene impeccably, as if Charlie’s an overgrown child who can’t decide whether he’s the bully or the bullied. He’s both physically imposing yet totally breakable, a wounded animal roaring once more before collapsing.

The scene carries both the relief of getting something off your chest, and the worried guilt that maybe you should’ve kept it to yourself. From the scene onwards, we follow Charlie as he tries to build something of a life between L.A and New York. The viewer sees in him all the flaws that Nicole spoke of, or perhaps we don’t, it entirely depends on our personal perspective. Baumbach never imposes his judgement, and thus allows the viewer to make their own mind up. Without question, more than a few arguments will have been sparked about rightness and wrongness. But that’s marriage, and that’s divorce: a picture so large that you can’t possibly see it all at once, and one that changes depending on how you view it.

This idea is encapsulated in another of the film’s best scenes, in which an external evaluator (Martha Kelly) spends the day at Charlie’s condo to observe his parenting. Who’s to say how Charlie would behave when unobserved? The mere act of being watched changes how a person behaves, and by this point Charlie and Nicole have both found that minor moments from their life can be weaponised by lawyers. Nicole having a few glasses of wine, when translated through the language of a lawyer, became alcohol dependency, just as a car-seat not clipped in by Charlie became dangerous parenting. A great deal depends on such banal encounters, so that a woman silently watching a guy as he looks after his son becomes as high-stakes as snipping the right coloured wires on a bomb. The scene is made uncomfortably hilarious by her utter blankness, her refusal to say much of anything, and the power placed on this unknowable, silent arbiter, an analogue for the audience.

Driver does incredible work here, as Charlie buzzes with quiet stress and a barely-hidden attitude that this whole process is stupid. However, just as Nicole is trying to establish her identity away from Charlie, Charlie is attempting to establish his identity as a loving father, which he doubtlessly is. But you’re defined by the way other people see you. Charlie knows he’d do anything for Henry, but what good is that if other people don’t. As directors and actors, Nicole and Charlie know a thing or two about performance, and so it becomes essential to perform heightened versions of themselves for others. It just so happens that in this scene, a stunt that he performs for Henry goes very wrong and Charlie is left bleeding on the kitchen floor. It’s a perfect, funny, tragic way to remind us of where Charlie is at that moment: trying to keep up an act, but accidentally revealing to the world that he is a walking wound, bleeding all over his faceless condo.

Who isn’t pretending, in some way, that everything is alright when they know full well that it isn’t? Marriage Story is a film about admitting things, to ourselves and others. No matter how agonising the process, it’s only after this that we can begin to get close to something like contentment. Charlie and Nicole may have destroyed each other, often against their wishes, but the film suggests that they can also rebuild and that their lives don’t have to exclude each other. Of course, there is still love, and you understand why. Never do you doubt that Nicole and Charlie adored each other and perhaps still do. And there’s hope in this. It’s not a cynical film. It holds a strong belief that people don’t want to do the things they do to each other.

But there exists an irony: for “somebody to know me too well”, as Charlie sings, you have to knock down a barrier. You have to change your way of living to let somebody in, and once you’ve done that, you’re no longer the person you were before. The singular you is not the same as the partnered you… you change when observed, and when married you’re always observed. You will always give up a part of yourself to be seen by another. But Baumbach doesn’t suggest that this is inherently a bad thing. It can be. But it also can be beautiful to be acknowledged on such a deep level. And there will never stop being a part of us that longs for it. It’s just a question of how you balance the contradiction of wanting to be your own person, while yearning to be validated by your proximity to another. To love and be loved despite that, despite all the confusion and complications and mistakes is, as Charlie sings, “being alive”.

USA | 2019 | 137 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

While Criterion Collection editions of Netflix Originals has been debated far and wide, this release should put to rest any argument that it’s a pointless endeavour. This release of Marriage Story feels much closer to how the film should be viewed, with richer picture quality than is afforded by streaming services, and a fuller sound mix. The film’s frequent use of music is wonderfully vibrant with this DTS-HD 5.1 Master Audio, while the 4K scan is crisp but keeps the 35mm film stock that the film uses looking faithful and textured.

writer & director: Noah Baumbach.

starring: Scarlett Johansson, Adam Driver, Laura Dern, Alan Alda, Ray Liotta, Julie Hagerty & Merritt Wever.