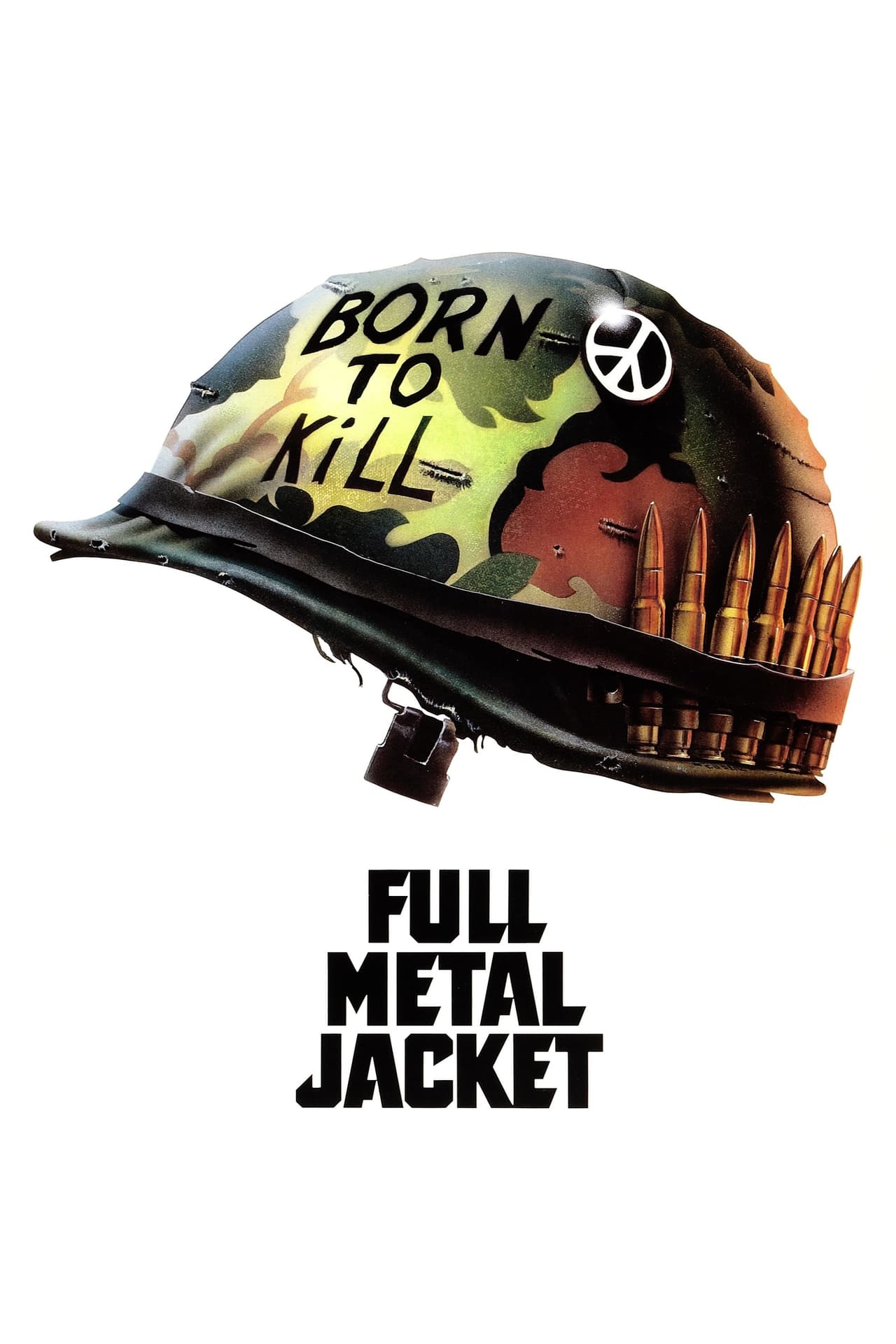

FULL METAL JACKET (1987)

A group of US Marine recruits go through basic training before being sent to Vietnam.

A group of US Marine recruits go through basic training before being sent to Vietnam.

Perfectionist as always and unable to risk anything slipping out of control, Full Metal Jacket saw Stanley Kubrick recreate a South Carolina military training facility in the fields of Cambridgeshire, England, and the Vietnamese city of Hue in an abandoned London gasworks complete with 100,000 plastic plants. It’s fitting, then, that one of the few things in Full Metal Jacket that’s almost real—the character of Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played by the ex-US Marine instructor R Lee Ermey, hired only as a technical consultant before yelling his way into the role—comes so close to destroying the film.

Not “destroying” in an entirely bad way, though. Hartman, the training sequences he dominates, and his relentless persecution of Private Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio), are the most attention-grabbing things in Full Metal Jacket, and the pair are certainly the most interesting characters and the best-remembered. But these parts of the film are so successful that they—and their shockingly violent conclusion—severely imbalance what must’ve been envisaged as a film of two relatively equal halves. Instead, the first part depicting the Marines’ basic training comes to dominate proceedings and could stand apart as a film of its own; while the second half, which follows a couple of the recruits to Vietnam, feels more like an epilogue or reflection. It’s engaging enough but dispensable.

Kubrick had made war movies before: most obviously Paths of Glory (1957) set during World War I, but his debut Fear and Desire (1952) also dealt with soldiers in an unidentified conflict, Dr Strangelove (1964) was concerned with the military while not involving combat directly, and warfare was also a major element of Spartacus (1960) and Barry Lyndon (1975). More immediately, Full Metal Jacket also arrived in the midst of a wave of Vietnam films like Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986), and Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978).

Though Kubrick insisted he was primarily attracted by Gustav Hasford’s novel itself, and by the idea of making a war movie in general rather than a Vietnam movie specifically, he was never one to shy away from controversial issues. And with something of an outsider’s perspective after moving away from his native US to the UK nearly three decades earlier, he clearly saw thought-provoking opportunities in one of the rawest aspects of recent American history.

Still, Full Metal Jacket isn’t solely concerned with the Vietnam war itself, but with the military and militarism in general, particularly (the film suggests) their ability to depersonalise teenage boys and turn them into killing machines. The opening montage of new Marine recruits having their heads shaved, removing one of the most immediate signs of individuality, makes this apparent (as well as typifying Kubrick’s eye for the arresting image); Johnny Wright’s “Hello Vietnam” on the soundtrack for this scene, with its repetition of the word “goodbye”, underlines the point.

Kubrick’s film, Academy Award-nominated for its screenplay, starts out by following Hasford’s book The Short-Timers relatively closely, although far more of the movie than the novel concentrates on the recruits’ training. Later, the screenplay (a joint venture of Kubrick, Michael Herr and Hasford) diverges further from the novel, blending its second and third sections with much of the third discarded.

Writing the film seems to have been an iterative effort, with Kubrick repeatedly reformulating the other men’s work, and there can be little doubt that the finished script aligns with the director’s vision, for all that he was an admirer of the Hasford book and of Herr’s own Vietnam memoir, Dispatches. (Herr, a journalist whose knowledge of war reporting may be reflected in the detail of military newspaper operations in Full Metal Jacket, had also written the narration for Apocalypse Now; he and Kubrick met through John le Carré.)

The first part of the movie takes place at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in Parris Island, South Carolina, where Ermey’s drill instructor Hartman verbally—and sometimes physically— beats into shape a platoon of new recruits, many of who he gives demeaning nicknames. Most important among them are Joker (Matthew Modine), an intelligent and quiet young man who is the film’s protagonist and speaks the occasional voiceover; Joker’s friend Cowboy (Arliss Howard); and D’Onofrio’s Pyle.

Unlike Joker, Pyle is unfit and seemingly not too bright either, as he can barely manage to pull himself over assault course obstacles and rests his rifle on the wrong shoulder—so his un-Marine-like sloppiness infuriates Hartman. The humiliations he inflicts on Pyle are brutal (in one scene the recruit is made to march behind the others with his trousers around his ankles, sucking his thumb) but they appear to pay off, at least in Hartman’s terms, as Pyle starts to excel at training and reveals himself to be a fine marksman; Joker has also played a part in this, patiently coaching Pyle in small tasks.

Hartman speaks the first line in the film, and for a long time thereafter there’s no dialogue that’s not either spoken by him or in response to him (and when it finally comes, it’s Joker showing Pyle how to strip his gun). Initially, indeed, it seems Hartman might overwhelm every scene, but Joker and Pyle gradually gain more emphasis too; a close-up of Joker as Hartman lays into Pyle is a very rare example of an uninvolved individual’s reaction being shown in this part of Full Metal Jacket, while Hartman’s praise for Joker—“silly and ignorant, but he’s got guts, and guts is enough”—is pretty much the first positive thing the older man says.

In a film where few of the recruits are granted any depth of characterisation at all, Joker’s also depicted as having mixed feelings about Pyle. When the others gang up on Pyle he does participate, after some hesitation, but is soon seen covering his ears to shut out the sound of Pyle crying.

The Hartman-Pyle thread, with Joker as essentially a concerned onlooker, builds to a sudden and horrific climax that far exceeds in nastiness what has gone before. The second part of Full Metal Jacket then abandons most of the individuals from the first section as it follows Joker to Vietnam, where he becomes a correspondent (really a propagandist) for the military newspaper Stars and Stripes. Keen to report on the fighting itself, he and his photographer Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard) hook up with Cowboy’s combat unit and become involved in the battle for the city of Hue during the 1968 Tet Offensive.

The mood shifts as much as the geography. Vietnam feels less real and also less threatening than Parris Island, and the Marines seem so much more at home here. A possible problem with the film is that, since we never meet them in their pre-Marine days, it’s impossible to tell how much of that is down to their training at the hands of Hartman and how much is simply down to their nature, but the way that the first section of Full Metal Jacket concentrates so much on the scrubbing away of their personalities and their remoulding as military men imply that what we are now seeing is what Hartman has created.

To some extent, the second part is a more conventional war movie with well-handled combat sequences where Kubrick takes care to make the spatial layout clear (“the terrain of small-unit action is really the story of the action”, he said). It benefits, too, from an unusual setting for Vietnam films: urban rather than jungle, with the defunct Beckton gasworks in London (also used as a setting for 1984’s 1984) chosen for their architectural resemblance to the city of Hue. Some of them had, indeed, been designed by the same French architect.

Full Metal Jacket is also said to be largely authentic in terms of the men’s attire, equipment, and so forth, with some exceptions (for example, the helicopters). But as Rodney Hill has written, it’s “more a ‘Kubrick film’ than it is a ‘Vietnam movie’”, despite a character in Full Metal Jacket (which has several scenes of troops being filmed or photographed) declaring that “this is Vietnam: The Movie.”

The director’s signatures are unmistakable: scenes that seem more choreographed than acted, slightly unreal dialogue (“we are jolly green giants walking the earth with guns”), a pervasive sense of detachment, irony, and even parody. Kubrick denied that several supposed references to his earlier work—a leer from Pyle that strongly resembles Jack Nicholson’s in The Shining, a 2001-ish monolith shape in the background of combat, a scene recalling Paths of Glory—were intentional, but a Kubrick film it undoubtedly is.

That also means credible or rounded characters take a distant second place to the overall effect. Still, several stand out, none more than Ermey’s Hartman with his fantastically baroque abuse of the recruits: about half of it improvised, some of it genuinely alarming to the rest of the cast, some of it funny to those of us lucky enough not to be experiencing it, much of it clearly designed for impact rather than literally meant although it is never possible to know which category a given statement falls into. (After announcing that he’s not racist, Ermey starts talking about “kikes” and “wops”, and informing a black recruit that fried chicken and watermelon aren’t available in the mess.)

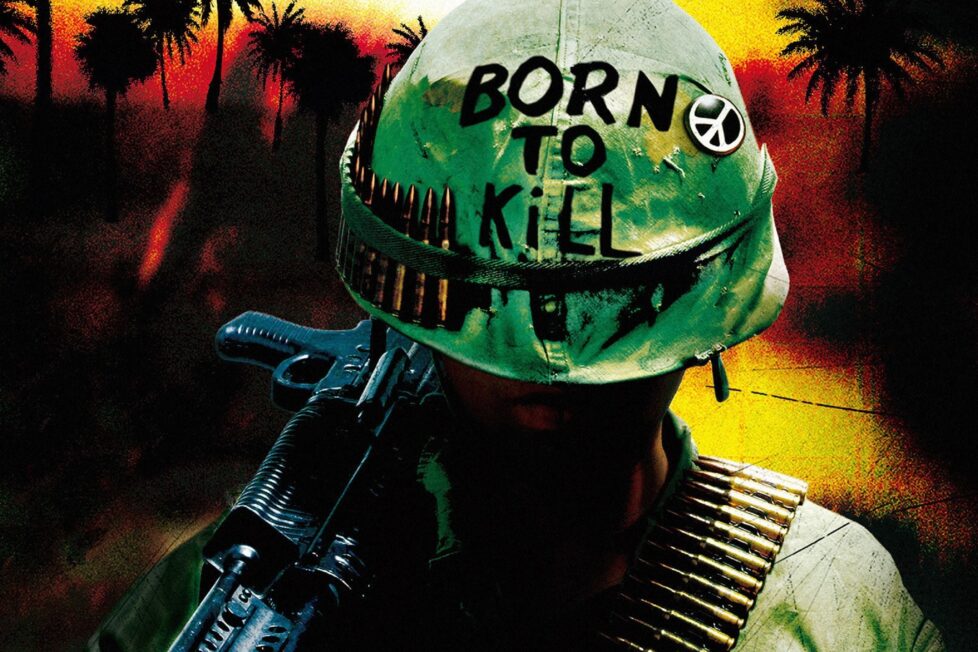

D’Onofrio’s Pyle, too, isn’t quickly forgotten and his transition from a bumbling, self-effacing, slightly comical and sad figure to an unbalanced and dangerous one is utterly devastating. By contrast Modine’s Joker, although the nominal focus of the film and the audience’s stand-in, is inscrutable; ‘Born to Kill’ scrawled on his helmet and the peace symbol on his chest cancel each other out.

Howard as Cowboy is at his best in a combat scene where he struggles to maintain control of his men, but the Vietnam sequences are more dominated by Adam Baldwin’s bloodthirsty Animal Mother; occasionally he has the same expression as Pyle, and it’s difficult not to think that this is what Pyle might have become, or what Hartman wanted him to become. The same is true, perhaps, of Tim Colceri as a kill-happy helicopter gunner.

There are few senior officers in Full Metal Jacket, though Bruce Boa’s colonel decrying the “peace craze” is amusingly reminiscent of Strangelove, and there is also some pointed humour in John Terry’s portrayal of Lieutenant Lockhart, a Stars and Stripes editor more interested in running stories about Ann-Margret visiting the troops than in rumours of a Viet Cong attack.

There are no female roles of any size at all (though a woman at the very end is significant). Full Metal Jacket hardly ever departs from the world of young Marines, and indeed Kubrick had originally intended to use actors the same age, though he eventually had to acknowledge they would be too immature for the parts and the actual cast are generally a little older than their characters.

Several of them die, but Kubrick covers this matter-of-factly, far from the tragic emphasis of Platoon. There are moments of beauty, moments of ghastliness, and some philosophising, but none of it is laid on very thick, and whereas many Vietnam films had mythologised the conflict, this dispassionate approach sharply divided critics. Janet Maslin in The New York Times called it “Kubrick’s most sobering vision… infinitely more troubling and singular than” Platoon. Jay Scott in the Toronto Globe and Mail thought it “may be the best war movie ever made”; Terrence Rafferty in Sight & Sound argued it was “one of the strangest war movies ever made” (and compared Pyle to 2001’s HAL); Pauline Kael said it “may be [Kubrick’s] worst movie” with its “emptiness.”

Perhaps because it nails no colours to the mast it hasn’t quite achieved the status of Platoon or Apocalypse Now, but it remains as influential as one would expect a Kubrick contribution to the corpus of Vietnam films to be. Just in recent years, for example, the episodic style of Da 5 Bloods (2020) and the basic training sequences in Cherry (2021) must have been influenced by Full Metal Jacket.

And even if it’s not a film that invites simple emotional takeaways or offers a clear moral perspective, it’s also not an easy one to ignore. Although it’s certainly interested in the way that the military transforms young men, its central concerns are much wider than this, and not confined to Vietnam or even to war: here we once again see the director’s characters trying, vainly, to control the world while it carries on around them in a way that often seems senseless.

The absurdity of the final Mickey Mouse song amid the ruins of Hue is not making a point about American youth or capitalist imperialism, but about the coexistence of apparently contradictory things in reality. Kubrick is not lecturing us (“you shouldn’t make a war film if all you have to say is, ‘there should be no more wars’”, he told Le Monde), just observing.

Even the final line spoken by Joker encapsulates such contradictions, simultaneously confirming how successful Hartman’s vicious training of his recruits turned out to be. Earlier in the film, when Pyle says “I am in a world of shit”, he may well be referring to the general nature of the world as well as his own position (not to mention his literal location in the barracks toilets). Lieutenant Lockhart’s observation that the latest turn in the war is “a huge shit sandwich and we’re all going to have to take a bite” can equally be given a much wider interpretation.

But at the conclusion, Joker adds a slightly different riff on this theme. “I am in a world of shit,” he says, “yes, but I am alive, and I am not afraid”. Whether this is a happy ending to Full Metal Jacket, a despairing one, or simply the statement of a man who no longer feels anything, is pointedly unclear.

UK • USA | 1987 | 116 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Stanley Kubrick.

writers: Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr & Gustav Hasford (based on the novel ‘The Short-Timers’ by Hasford).

starring: Matthew Modine, Adam Baldwin, Vincent D’Onofrio & R Lee Ermey.