THE BETRAYAL (1966)

A naively honourable samurai comes to the bitter realisation that his devotion to moral samurai principles makes him an oddity among his peers...

A naively honourable samurai comes to the bitter realisation that his devotion to moral samurai principles makes him an oddity among his peers...

Tokuzô Tanaka’s The Betrayal / Daisatsujin orochi showcases some quality swordplay and boasts what is certainly the most epic one-man-versus-many sequence of any classic chanbara movie. Perhaps not the best samurai movie to come out of the 1960s, after all there’s some stiff competition, but the finale where a lone outcast makes a stand against two armies of samurai, one of them from his own former clan, is essential viewing. Along with a fine central performance from Daiei Studio’s superstar Raizô Ichikawa, it’s the reason why it’s still held in such esteem. This new HD digital transfer, overseen by the Kadokawa Corporation and presented on Blu-ray from Radiance, will be welcomed by those with any serious interest in samurai cinema.

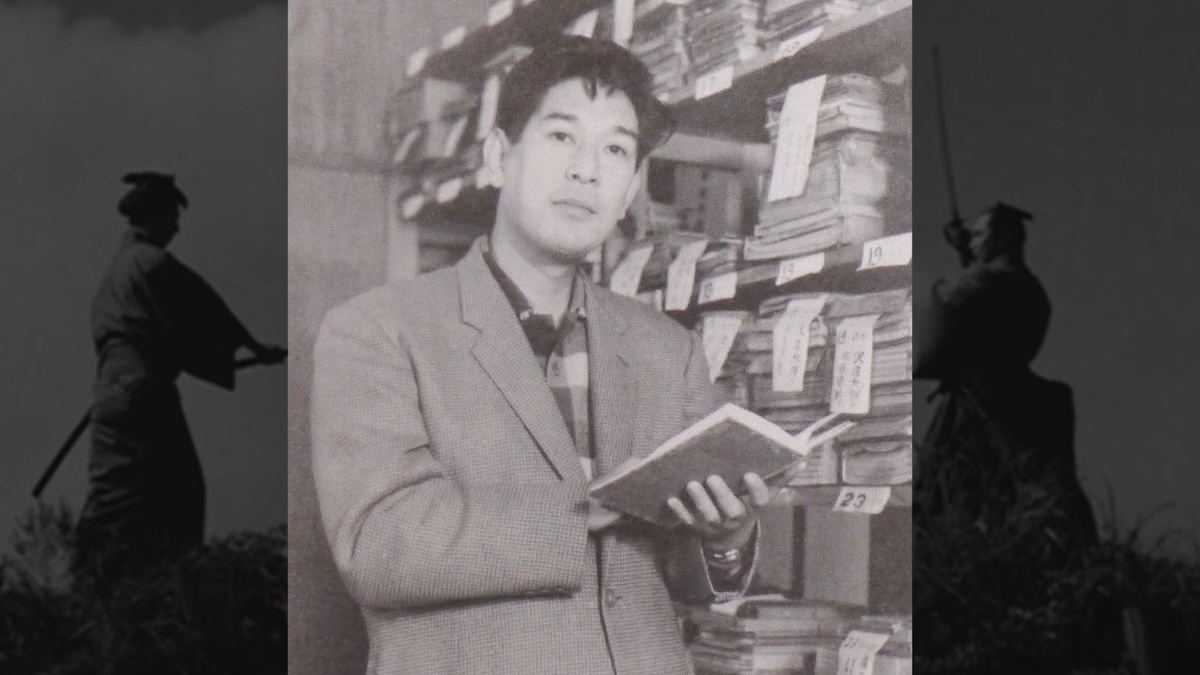

Tokuzô Tanaka had a good introduction to filmmaking as assistant director for two of the greats: Akira Kurosawa on Rashomon (1950) and then Kenji Mizoguchi on Ugetsu (1953). In many ways, The Betrayal feels like an early career movie, but he was such a hard-working director that he’d already helmed more than 30, including half a dozen entries in his Bad Reputation yakuza series, a couple of Zatoichi movies, the first in the hugely popular Sleepy Eyes of Death franchise, The Chinese Jade (1963), and Shinobi 4: Siege (1964). He’d go on to accrue some 70 directorial credits in a career spanning more than four decades, proving to be reliable across several genres but, for me, his strength seems to lie in handling poetic gothic ghost stories. One would be hard-pushed to find a more beautiful and moving movie than his version of the classic Japanese folktale The Snow Woman (1968), released as part of last year’s Daiei Gothic box set, also from Radiance. Another couple of his visually arresting supernatural films, The Demon of Mount Oe (1960) and The Haunted Castle (1969), are showcased in their forthcoming follow-up box set, ‘Daiei Gothic Vol. 2.’

So, it’s great to see more of Tokuzô Tanaka’s movies resurfacing for reappraisal after being dismissed as a B-movie director for too long. As with pulp genres such as noir in mid-century France and the US, the giallo or Euro-western in 1960s-1970s Italy, Japan has churned out chanbara movies since the dawn of cinema. In the heyday of Japan’s studio system, the two major players, Toho and, in this case, Daiei, had costumes, standing sets, and talent under contract ready to produce these crowd-pleasers efficiently and comparatively cheaply.

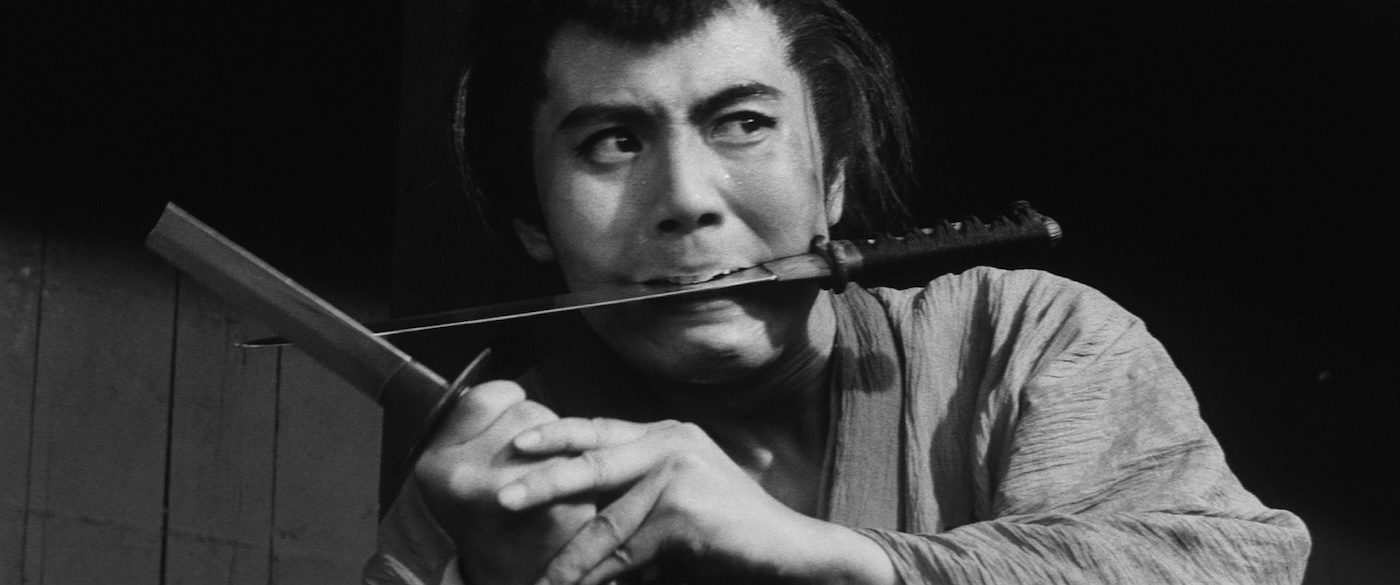

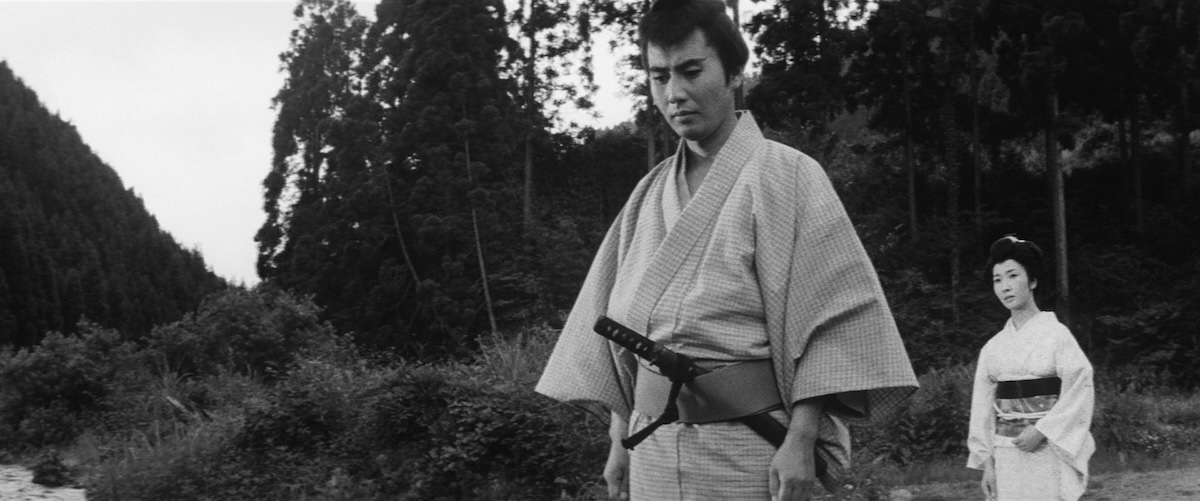

That Raizô Ichikawa, the star of both the Shinobi and Sleepy Eyes of Death franchises, is cast as the lead here indicates that the executives at Daiei believed The Betrayal to have above-average potential. Or maybe they knew it really needed the pull of their most popular superstar. Either way, he’s the perfect choice, and his central performance dominates the proceedings. It may seem easy to play a disciplined, comparatively inexpressive samurai but it takes a special skill to be able to convey emotional subtext between sparse, often matter-of-fact dialogue. A well-timed micro-expression, or even a mask-like absence of one, must do all the emotional lifting while upholding the stoic stillness expected of a movie samurai. Raizô Ichikawa can also be convincingly dynamic in action and is one of the masters of ‘whole-body’ physical performance. In this respect, he should really come to mind as readily as Toshiro Mifune and Tatsuya Nakadai but he’s only recently getting noticed by a wider audience outside Japan.

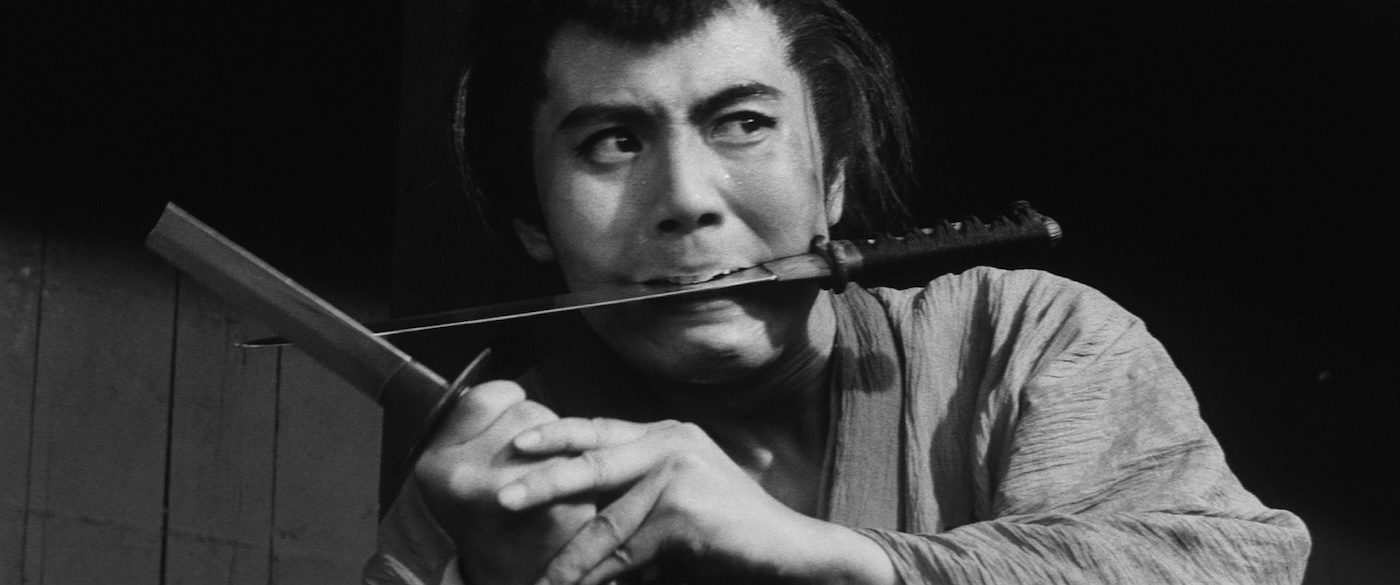

Comparisons with Kihachi Okamoto’s superior Sword of Doom (1966), released four months earlier and starring Tatsuya Nakadai, are unavoidable as both films follow a similar narrative trajectory, feature an outcast samurai, and end with brilliant battle set-pieces where one man faces insurmountable odds against multiple adversaries. However, The Betrayal’s Kobuse Takuma (Raizô Ichikawa) is a good, though troubled, man wrestling with the conflict between truth and justice versus honour and obligation. On the other hand, Sword of Doom’s Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai) is a psychotic killer with few redeeming qualities who weaponises the samurai code to enable his fetishisation of blood and death.

Yet the similarities are striking enough that one can’t help thinking that maybe The Betrayal was rushed through production to ride the coattails of Sword of Doom. Possibly. But it started out as a remake of Buntarō Futagawa’s seminal Orochi / The Serpent (1925), which also builds to an epic finale of one man against many. It’s the first known movie to tell the tale of a rōnin and one of the earliest Japanese films created specifically for the screen—not an adaptation from a kabuki play. I recently viewed it in its entirety for the first time and thought it was incredibly modern for a film marking its centenary this year, as it steps away from that ‘filmed stage play’ approach, instead introducing an entirely new visual grammar. Buntarō Futagawa employed camera and editing in what was then a bold new narrative style—what would be known as montage technique, more often associated with Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, exemplified in his classic films made the same year, Strike (1925) and The Battleship Potemkin (1925). Interestingly, Eisenstein was studying the Japanese language and calligraphy as early as 1920, citing the pictorial nature of kanji and the staging of kabuki plays as influences on his own visual aesthetic.

Later, in 1928, when the great Japanese kabuki actor Sadanji Ichikawa II was performing in Moscow, Eisenstein made a point of meeting him. Please allow me to digress here for a little round of ‘6 Degrees of Raizô Ichikawa’: now, kabuki acting has a very strict structure of master and disciples. Special disciples are sometimes legally adopted by their master, changing their name to join esteemed lineages of kabuki ‘families’. One of Sadanji Ichikawa II’s disciples was Ichikawa Kudanji III who would later adopt a 15-year-old boy to be his son and disciple who then assumed the name of Ichikawa Enzō. Later, in 1951, the lad was adopted by another kabuki master, Ichikawa Jūkai III, and this time took the name of Ichikawa Raizō VIII. His stage performances garnered positive reviews, and he became a respected kabuki performer but, by 1954, he was transitioning to screen acting and had dropped the number suffix from his name to become Raizō Ichikawa.

In Orochi, the protagonist, Heizaburo (Tsumasaburō Bandō), is insulted by a samurai of a higher-ranking family but instead of simply taking the abuse, he speaks up and takes action but is then punished for his insubordination. Being a samurai, he won’t back down and ends up an outlaw, shunned by his clan and wider society. The original title was to be ‘Outlaw’ but the Imperialist regime wouldn’t allow a man who dares to question the strictly hierarchical society to be romanticised for breaking the rules. So, the film closes with a prolonged battle ending in his arrest. The story took risks in its critique of the reactionary socio-political structure, and so the film could only get past the censors if the protagonist ultimately failed to change the status quo. Thus, the narrative cleverly questions the social order of Imperialist Japan while navigating the mechanisms of censorship serving its ideology. Quite brave for its time, both in its content and creativity.

The story of The Betrayal isn’t directly transposed from Orochi but has been reworked and embellished. Kashiyama Denshichiro (Ryûtarô Gomi), a samurai of the dominant Iwashiro clan, arrives at the training dojo of the Minazuki clan demanding a contest. His request is politely declined by Kobuse Takuma (Raizō Ichikawa) who explains that their master, Isaka Yaichiro (Asao Uchida), is not available. What Takuma did there was cleverly use the samurai code to manipulate the aggressor. By reporting the master’s absence, he acknowledged Denshichiro’s high rank because etiquette dictates that samurai only engage in combat with those of similar ranking. At the same time, he’s implying that as a mere ‘assistant instructor’ it would be inappropriate for him to stand in for his master and would be an insult even to suggest this. Linguistically outmanoeuvred in a few sentences, Denshichiro leaves in a huff and as he passes a couple of Minazuki samurai they exchange insults. One of the young samurai, Mannosuke Katagiri (Sei Hiraizumi), dismounts and draws his sword but Denshichiro only laughs at his audacity. As we were just reminded at the dojo, it’s insulting for a samurai to fight another of a lower rank so turning his back on Katagiri is doubly insulting, and the young hothead deals a mortal sword slash from behind.

Killing a samurai from a rival clan over something so petty is enough to provoke a war and it seems that’s what Denshichiro was trying to engineer in the first place, to create an excuse for his bigger clan to take the land and wealth of their neighbouring lord Katagiri (Shôzô Nanbu). Yes, at least trying to keep track of the many names does pay off here as we soon realise that the murderous young samurai is the son and heir to one of the Minazuki clan’s highest-ranking families. Attempting to avert a clan war, Lord Katagiri comes up with a terrible plan.

He asks Kobuse Takuma to postpone his pending marriage to his daughter, Namie Katagiri (Kaoru Yachigusa), so Takuma can leave and go into hiding. In samurai circles, an ask from a superior is pretty much the same as an order so he agrees. The plan is to imply that Takuma is responsible for killing Denshichiro to divert suspicion from Mannosuke. Lord Katagiri promises to find a solution and make peace between the clans over the year and if it doesn’t work out, he will clear Takuma’s name and commit seppuku. However, the plan didn’t have a contingency in the event of Lord Katagiri’s sudden death from natural causes…

So now Takuma is on the run from his own clan who feel the only way to restore their honour is to deliver the head of Denshichiro’s murderer to the Iwashiro clan. The only people who know he’s innocent are his fiancée, who wouldn’t be believed, the actual killer, Mannosuke, who’s fine with keeping quiet to save his own dishonourable neck, and the other samurai at the scene of the crime, Jurota (Ichirô Nakatani), who covets Namie and wants to marry her in Takuma’s absence.

Some of the plot points seem a little contrived at times but only because the narrative is so honed that every event and line of dialogue is deliberately there to pull the story along. This sense of artifice gets in the way of viewer immersion. Also, the pacing slows in the second act to convey that passing of time, but this inevitably slows things down in a narrative sense, too.

There are enough brilliant swordplay set-pieces to satisfy fans of the genre. These fight scenes aren’t only for show as each propels the narrative, especially when Takuma’s own clan catch up and his sensei, Master Isaka Yaichiro, chooses to honour him by being the one to finish it. Without giving too much away, Takuma narrowly escapes with a severe injury. The how and why this happens only really sinks in when we see him in action during the final battle.

The cinematography of Chikashi Makiura is so uneven I wonder if some of the scenes were handled by a second unit supervised by the less experienced Showa Ota, but they were up against a tight schedule and probably had to go with what they managed to capture on the day. Some of the camera work is rather jerky in a way that doesn’t seem intentional, whereas the shots zooming from extreme wide to medium or even close-up shots remain impressive to this day. The interiors are beautifully framed and lit and there are some strong visual compositions throughout. Clearly, though, the most time, effort, and budget went into the amazing finale, trying to clear the high bar set by Akira Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai (1954) with spectacular swordplay sustained through an epic fight sequence. The scene blocking and filming of the epic fight is superlative with stunt design and fight choreography by Shôhei Miyauchi.

The finale is as realistic in some respects as it is unrealistic in others. The idea that a single samurai stood any chance at all against around 200 opponents is not as far-fetched as it sounds. In his classic treatise on samurai strategy and combat with the long sword, The Book of Five Rings, Miyamoto Musashi reasoned that, “If he attains the virtue of the long sword, one man can beat ten men. Just as one man can beat ten, so a hundred men can beat a thousand, and a thousand can beat ten thousand. In my strategy, one man is the same as ten thousand…” Thus, he extrapolates that the number of assailants that can engage a samurai in combat is limited by the length of a katana, and the radius of its swing. One warrior can only be attacked by a circle of eight or ten adversaries at a time. So, it doesn’t matter how many there are, a swordsman can only fight ten at a time and the number of enemies they may dispatch is limited only by their stamina.

The last stand of Takuma against the men of two clans displays both his samurai sword skills and waning stamina as he repeatedly staggers and slumps under the relentless onslaught. There’s an unrealistic absence of blood and severed limbs, which some viewers may be thankful for. Really that doesn’t detract from the dynamic fight choreography, but it does remove any visceral sense of realism and reduces emotional engagement. Ichikawa’s performance more than makes up for this, though, and it’s still gripping. Luckily none of those involved resort to archery and no one brought a musket or cannon otherwise the film would’ve been about 20 minutes shorter.

Sword of Doom has a more intense and emotionally engaging finale fight, and the moderate blood spray has an effect on the viewer that just isn’t there with The Betrayal. The epic battle may not appeal to the same audience who enjoyed the quieter philosophical narrative, just as that may bore those here for the fight sequences. It delivers both aspects with above-average competence and should still appeal to anyone who enjoys quality chanbara and jidaigeki.

JAPAN | 1966 | 87 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

director: Tokuzô Tanaka.

writers: Seiji Hoshikawa, Tsutomu Nakamura (from an idea by Rokuhei Susukita, based on the 1925 film Orochi / The Serpent).

starring: Raizô Ichikawa, Kaoru Yachigusa, Shiho Fujimura, Ichirô Nakatani, Ryûtarô Gomi, Taketoshi Naitô.