SEVEN SAMURAI (1954)

Farmers from a village exploited by bandits hire a veteran samurai for protection, who gathers six other samurai to join him.

Farmers from a village exploited by bandits hire a veteran samurai for protection, who gathers six other samurai to join him.

On a black screen, drums create a powerful, sinister rhythm. As the credits roll, the pulsating beat seems to foreshadow imminent violence, portending a primal struggle for survival. It’s the marching hymn of medieval warriors, clad in armour and charging headlong onto the battlefield.

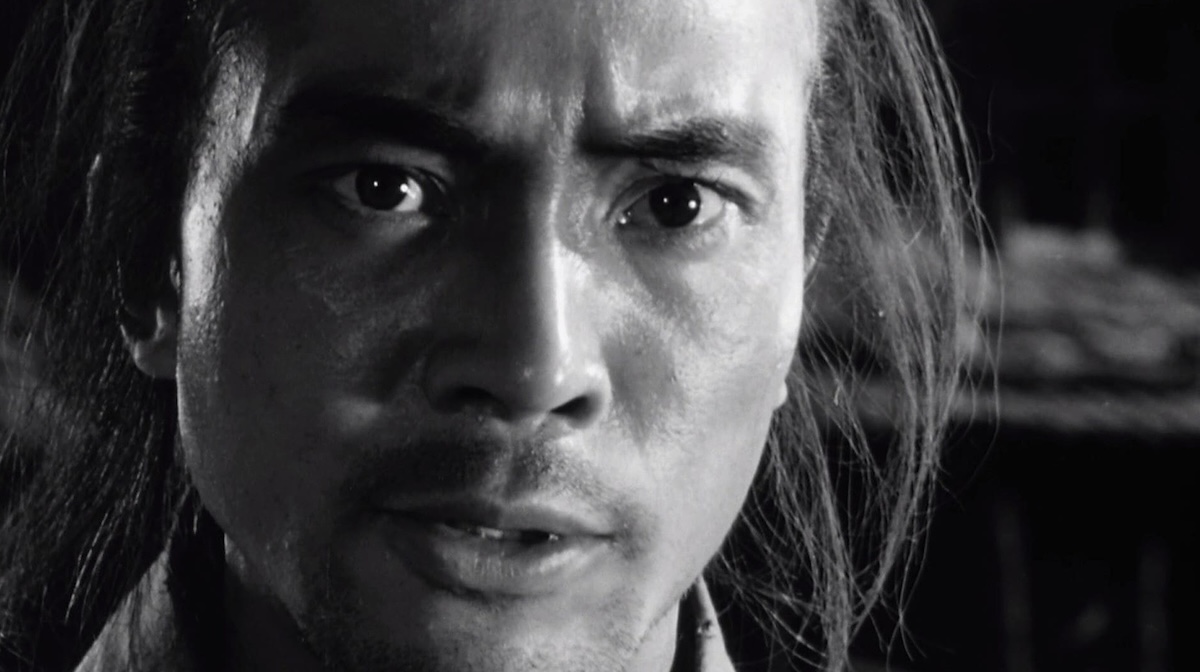

Indeed, war looms on the horizon. A battalion of bandits rides across rural Japan, slaying farmers, kidnapping women, and stealing their produce. They’re a scourge to any peasant who has to work the land for a living—and they show no signs of stopping. After a farmer overhears the bandits’ plan to attack their village in the near future, he warns his fellow villagers, most of whom fear they are utterly helpless. However, some have had enough: Rikichi (Yoshio Tsuchiya) wants to fight. “We’ll kill these bandits… We’ll kill them all!”

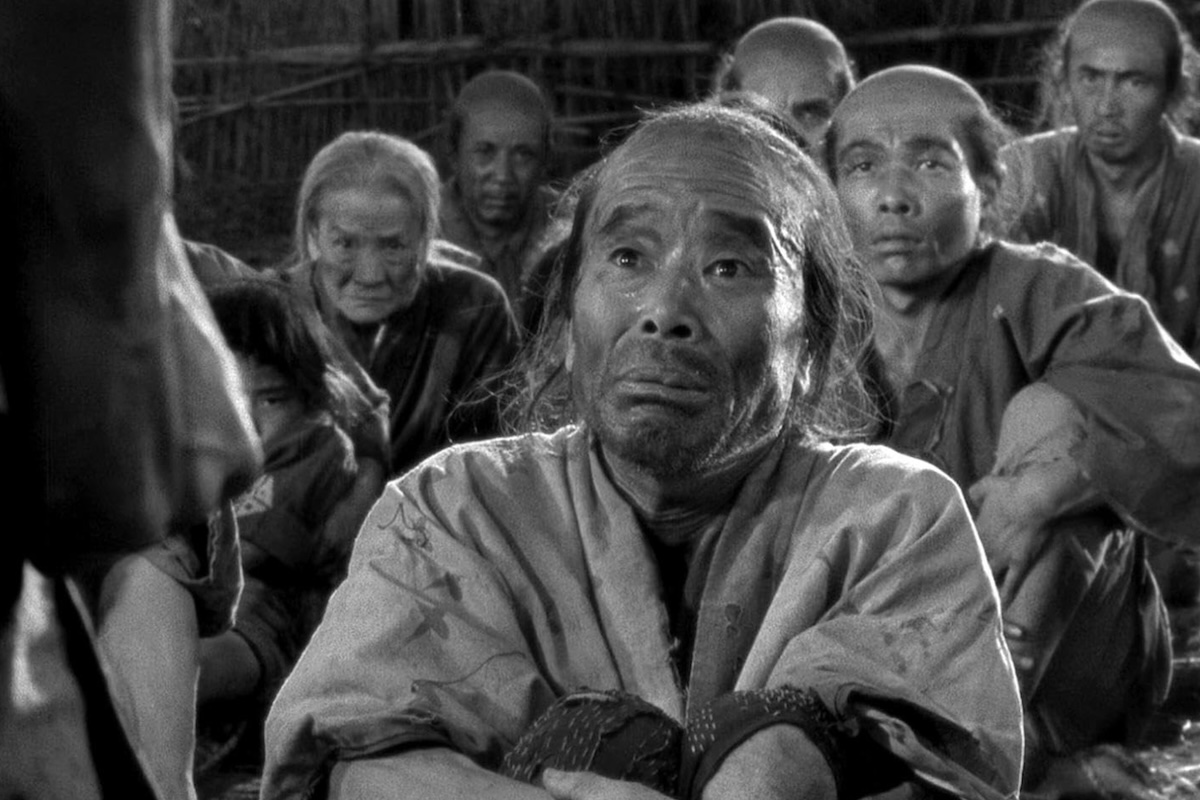

Unfortunately for the poor farming village, they are no match for a band of 40 heavily armed rogues. At their wits’ end, Rikichi seeks advice from the village sage, Gisaku (Kokuten Kōdō), in their desperate hour of need. His answer? Hire samurai to defend them from the impending attack. When Rikichi protests, claiming they’re too poor to afford protection, the village elder replies: “Find hungry samurai. Even bears come down from the mountains when they are hungry.”

Akira Kurosawa’s masterpiece, Seven Samurai / 七人の侍, is considered by many to be amongst the best films ever made. It’s a statement that’s hard to disagree with: there is simply so much that transpires in Kurosawa’s longest work, with the 207-minute runtime never feeling a second too long. It is a character-driven epic, a period drama that captures the feeling of living in such a desperate time with raw authenticity, and a story that has influenced countless imitators, from Star Wars (1977) to Home Alone (1990), from Rio Bravo (1959) to The Avengers (2012). Simply put, Kurosawa’s magnum opus, which turns 70 years old this year, is arguably the greatest action film ever made.

Truly, the story of Seven Samurai seems so perfect that it’s hard to believe it wasn’t the intended story at all. Originally, Kurosawa intended to make an anthology film, following the lives and trials of five different samurai. Scrapping this concept, he decided to make a film that focused on a single day in the life of one samurai, from the minute he woke up to the moment he lay his head down to rest again.

Having discarded both ideas, Kurosawa then came across a story set during Japan’s Warring States period, which spanned a century from 1467 to 1567. The anecdote recounted how samurai offered their protection to peasants in exchange for food. Having been rendered masterless by this tumultuous period in their nation’s history, a samurai became a ronin, forced to take whatever work they could find. In this time of upheaval, a samurai might agree to defend a peasant village in exchange for board and lodging.

Hearing this idea, it’s easy to see how the story practically writes itself. That’s because this kind of tale has a timeless appeal: the desire to protect one’s home from foreign invaders. Kurosawa’s film taps into something profoundly primal in the human condition. The villagers want to defend their homeland and the fruits of their labour from those who seek to destroy them and leave them to starve; the theme of self-preservation is immediately recognisable.

As the peasants resolve to make a stand, to draw a line in the sand and declare, “This is mine, you shall not take it,” we wholeheartedly empathise with their plight. It elicits a visceral response from the viewer because it’s easy to imagine ourselves in the same desperate situation. For this reason, the theme of borders being encroached upon and violated by malicious forces is a motif that many a war film has utilised.

Kurosawa cleverly employs this theme visually through a montage of the peasants fortifying their homes with barricades, pitfalls, and hidden dangers. All this is done under the samurai’s instruction; they are preparing for battle and we watch with anticipation throughout. Here, the parallels between Kurosawa’s jidaigeki and Chris Columbus’s Home Alone become clear: a young boy defends his home from foreign invaders, using nothing but an elaborate set of traps.

This, if nothing else, demonstrates both the universal appeal and the evergreen themes present in Seven Samurai. While Macauley Culkin’s Kevin relies on a swinging bowling ball and nails in floorboards, our samurai employ scarecrows, ditches, fences, and flooded fields to defend their village. Such tricks ensure our resourceful heroes remain one step ahead. There’s considerably more death and despair in Kurosawa’s film, but unsurprisingly these elements were omitted in Columbus’s family-friendly classic.

Kurosawa never lets audiences forget his background as a painter. The Japanese auteur creates some sequences that have a lasting impact on the viewer—the poetry of his imagery is stunning. Men wade through the water naked, fleeing attackers only to be cut down in the marsh. A woman wanders into the flames of a burning building, choosing a fiery death over life in a world filled with pain and suffering.

There are many reasons behind the enduring appeal of Kurosawa’s action epic, but undoubtedly one of them is his ability to capture scenes akin to myth. Samurai stand stoically in the rain on the cusp of battle, awaiting the coming onslaught hidden within the forest. A fire blazes in the night as two lovers embrace, both fearing they will die in the morning. Four swords thrust into the earth sway mournfully in the wind, placed in remembrance of the fallen. And a farmer-turned-samurai clutches blood-slick swords in both hands, fighting for both vengeance and redemption. The tale transcends cinema and becomes the stuff of legend.

Of course, the great director’s visual competency never overshadows his storytelling prowess. The screenplay, co-written by Kurosawa with screenwriters Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni, boasts terrific structure and pacing. It also features a plot point that has since become a hallmark of many an action film: the assembling of an elite team. The influence on films like The Avengers and Rio Bravo is evident; we’re introduced to key characters as the narrative simultaneously builds momentum.

In fact, what’s startling is how a formative action film like this one has absolutely no action until well over two hours in. Compare this to the likes of Die Hard (1988), a film that many cinephiles would place at the top of their list of best action movies. While it’s true they belong to the same genre, it seems to me that the two films are fundamentally different and can barely be compared. Die Hard is the epitome of a classic American action flick: packed with one-liners, fisticuffs, and plenty of thrilling shoot-outs. It’s terrific entertainment with a fantastic protagonist.

In the meantime, Seven Samurai feels largely distinct from this type of film. It’s the product of a genuine artist and storyteller, one who’s readily willing to forgo thrills in favour of insightful social commentary and meaningful character development. Fortunately, Kurosawa doesn’t have to make a choice—he deftly creates some of the most exhilarating action sequences ever made.

There’s so much going on beyond the battle sequences that it even feels like an understatement to label Kurosawa’s masterpiece as purely an action film. This 1954 classic straddles so many genres that it’s difficult to pin it down to just one. It’s a love story, a social drama, an epic adventure, historical fiction, and even a tale of existential exploration. As characters discuss their fears of what awaits them in the great beyond, the question of life’s meaning becomes a dominant theme in the narrative. The farmers frequently question the purpose of their lives, even contemplating suicide as a possible escape from their wretched existence.

In the same way that the peasants grapple with the question of whether the bandits will ever ransack their village, the entire story begins to take on shades of Waiting for Godot (1953). It’s unlikely, of course, that Kurosawa would have read it at the time the film was made. Nevertheless, it’s interesting to note some of the similarities between the narratives. Beckett’s play has been interpreted as a metaphor for the meaninglessness of human existence, particularly when focused on waiting for salvation from an external source. This description could be equally applied to the behaviour of the villagers, with the only difference being that the bandits do actually appear.

Of course, that’s when the action really gets going. For all those who didn’t make it to the interval, they unwittingly walked out on 90 minutes of brilliant mayhem. The set pieces are breathtaking and you’re left astonished at the scale of the production; with the scope on display, you suddenly understand why it quickly became Japan’s most expensive film.

Kurosawa captures every moment of visceral warfare: swords, fire, and men yanked from their horses. After the preceding two hours of set-up, the surge of adrenaline is palpable. Needless to say, despite all the genres that co-exist in this film, there’s a reason why it’s sincerely considered to be the greatest action film of all time.

Lacking the gift of foresight, studio executives at Toho feared they were creating a massively expensive box-office disaster. The production vastly exceeded its budget and schedule, with filming taking over four times longer than originally intended. This brought Kurosawa into the crosshairs of the executives, who threatened to cancel the film on several occasions.

In response, what did Kurosawa do? He simply went fishing. This phlegmatic reaction stemmed from his belief that, having invested so much money in the film, they would never cancel it. Needless to say, he was correct. Despite their anxieties that Kurosawa was creating a time-consuming flop, they allowed him to finish it unimpeded.

The final product was revered abroad (although 50 minutes had been cut from Kurosawa’s version). However, it wasn’t appreciated in Kurosawa’s native Japan by critics, who were perhaps blissfully unaware of the fact that they were living through the Golden Age of Japanese Cinema. The disdain from critics could be a result of Kurosawa’s rather merciless view of their national history. Indeed, our heroic samurai, who are the very embodiment of Japanese militarism, are revealed to be contemptible figures, ostracised by society.

When the samurai discover that the villagers may have killed samurai, taking their armour and weapons in the aftermath, they’re appalled. But Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune) is quick to remind them: “But then who made them such beasts? You did! You samurai did it! You burn their villages! Destroy their farms! Steal their food! Force them to labour! Take their women! And you kill them if they resist! So what should farmers do?”

The world-renowned warriors, whose very name has become synonymous with nobility, discipline, and skill, are shown to be little more than thugs. Here, the samurai occupy a contentious position in history. Certainly, they weren’t held in high regard by the peasants of medieval Japan, who felt oppressed by an elitist, class-based society, with samurai acting as brutal mercenaries for whichever tyrant happened to be in power.

Kurosawa, however, tackles this issue head-on. The samurai are forced to confront the reputation their class has earned. Much like some of the gunslingers in Western films, our samurai heroes are depicted as violent forces seemingly only capable of brutality. Similar to our eponymous protagonist in the classic Western Shane (1953), once the need for violent upheaval has passed, our heroes become redundant figures in society. Adrift once more, they are left without purpose.

There’s a tinge of melancholy in Kurosawa’s film, consequently. The work occasionally feels like a love letter to a bygone era: we’re witnessing the epilogue of samurai culture. The arrival of new technology is shown to be the downfall of the samurai class: it’s the power of the musket that fells each of our heroes.

They are more skilled with a sword than any living man, but it’s a skill that has become practically valueless in the modern era. The Last of the Mohicans (1992) explores a similar theme, where all the attributes the Mohicans possess cannot protect them from the unstoppable march of colonialism, fuelled by powerful new technology. Though the samurai are victorious, it’s a Pyrrhic victory. They have secured the survival of the village, yet their own future remains uncertain at best.

They become tragic heroes. Indeed, the power of archetypes is present in many of Kurosawa’s films, but it’s particularly noteworthy here. Earlier, I mentioned how the film feels akin to a myth, and this can be seen in how the characters are shaped: the wise man, the stoic leader, the mercurial wildcard, the young hero, the jester with a heart of gold, and the disciplined assassin. Each plays an integral role in the story.

Kambei Shimada (Takashi Shimura), who speaks in aphorisms as though directly quoting Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, acts as the father figure for our ragtag band of misfit samurai. Through him, we also experience the sense that his way of life is reaching its end: his culture is dying, presenting a conclusion that both confuses and frightens him. At the other end of the spectrum, Kikuchiyo acts as a bridge between two cultures—that of the peasant farmer and the elitist samurai.

As the first half of the story is essentially devoted to character development, it’s evident that Kurosawa is deeply interested in everything that happens in the lives of these protagonists. Though they are archetypes, he simply uses these readily comprehensible character templates to explore a theme or a deeper personality beneath the surface. As a result of this, each death feels like a tremendous loss.

Kurosawa’s film has probably influenced your favourite movie or filmmaker in some way. The battle sequences in both Braveheart (1995) and Gladiator (2000) bear a striking resemblance to these epic films, while American filmmakers like John Sturges simply remade the entire film with a Western setting in The Magnificent Seven (1960). This wouldn’t be the last time Kurosawa’s cinema was copied—we’re looking at you, Leone…

But, unsurprisingly, filmmakers have taken so much inspiration from the Japanese director. Despite the legions of imitators, his films are wholly inimitable. His cinema was starkly unique, filled with both emotion and adventure. From his action films like The Hidden Fortress (1958) to his character-driven tales like Ikiru (1952), no one quite had the same magic touch as this singular auteur. But when he combined character and adventure, he created something altogether unparalleled. And that, precisely, is what Seven Samurai is: an unrivalled, untouchable masterpiece.

JAPAN | 1954 | 207 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHTE | JAPANESE

director: Akira Kurosawa.

writers: Akira Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto & Hideo Oguni.

starring: Takashi Shimura, Yoshio Inaba, Daisuke Katō, Seiji Miyaguchi, Minoru Chiaki, Isao Kimura, Toshiro Mifune, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Bokuzen Hidari, Yukiko Shimazaki, Kamatari Fujiwara, Keiko Tsushima, Kokuten Kōdō & Yoshio Kosugi.