ANATOMY OF A MURDER (1959)

In a murder trial, the defendant says he suffered temporary insanity after the victim raped his wife. What is the truth, and will he win his case?

In a murder trial, the defendant says he suffered temporary insanity after the victim raped his wife. What is the truth, and will he win his case?

I’m not saying this is the best courtroom drama ever made. It’s not a genre that I’m usually attracted to. I’m no aficionado and, scanning down the American Bar Association’s list of the 25 ‘Greatest Legal Movies’ of all time, there were only half a dozen I could recall seeing. But there’s a good reason why Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder remained at number four more than half a century after its release. To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) is the chart-topper, with 12 Angry Men (1957) and My Cousin Vinny (1992) taking the number two and three slots respectively. But it’s Billy Wilder’s classic courtroom drama, Witness for the Prosecution (1957), lagging just behind at number six in that chart, to which Preminger owes a debt.

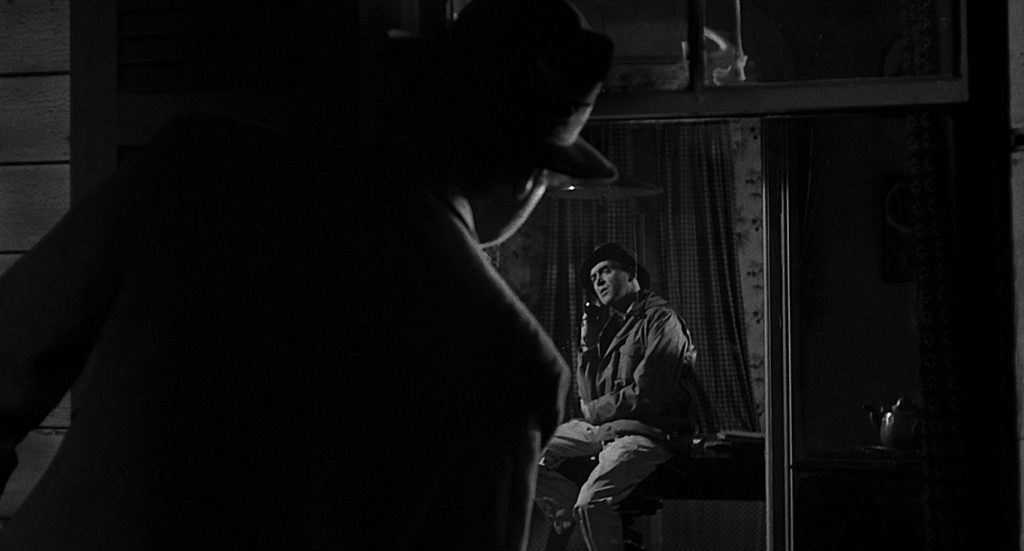

On the night of 30 July 1952, something happened between a former police officer called Maurice Chenoweth and Charlotte Peterson, in a car just outside the trailer park where she lived with her husband Lt. Coleman Peterson, an army lieutenant and veteran of the Korean War. Just after midnight, Chenoweth was lying dead behind the bar of the tavern he now ran in Big Bay, Michigan. A roomful of witnesses saw Lt. Peterson walk calmly in and, without saying a word, empty his Luger automatic pistol into Chenoweth. Surely, there could be no doubt of ‘murder in the first degree’? Here’s a tip, if you want to enjoy the film without spoilers, don’t Google any of those names!

The film is faithfully adapted from the 1957 best-selling novel by ‘Robert Traver’, the nom de plume of Michigan Supreme Court Justice John D. Voelker, who’d been Lt. Peterson’s Defence Attorney in the real trial. A year after the film was released, Hazel Wheeler, Chenoweth’s widow, and Terry Ann Chenoweth, his daughter, filed an unsuccessful joint suit for personal damages due to libel and invasion of privacy against publishers of the novel, Dell and Columbia Pictures. The story does retain nearly all the pertinent legal points of the murder trial, but names and scenarios had been changed enough. Not much, but enough.

Its accurate realism and attention to the detail in the portrayal of legal proceedings in the 1950s makes it very much of its day and thus renders it a near-perfect period piece for today. It’s no wonder Anatomy of a Murder is still held in such esteem by the legal profession and remains recommended viewing for Law Students.

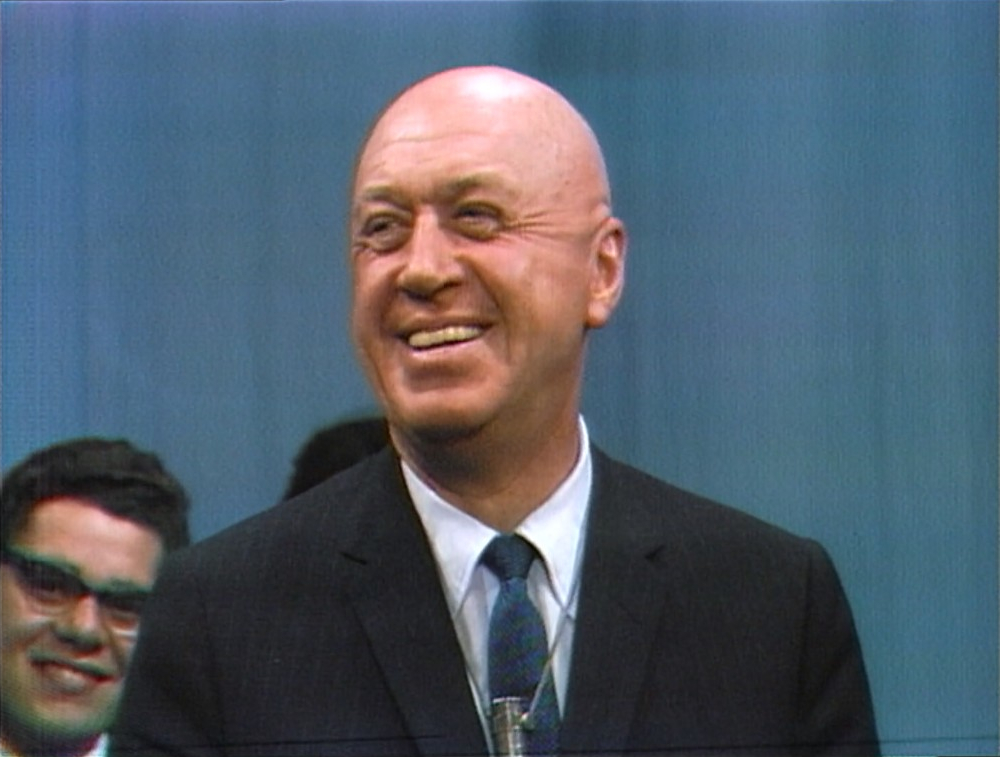

The original novel was written by a genuine high-ranking judge based on a real case he’d been directly involved with, and Voelker gave Wendell Mayes’s screenplay his seal of approval. The director, Otto Preminger, was also well-qualified, having graduated from Law School in Vienna before pursuing his stage and screen career. And if that wasn’t enough, he cast Joseph N. Welch as Judge Weaver and, at the time, the presence of Welch would’ve added a whole extra layer to the film in the public consciousness.

Courtroom dramas were a popular sub-genre in the late-’50s with America still reeling from the ‘Red Scare’ of McCarthyism (when many Hollywood stars were put on trial for being Communists or Communist sympathisers). Many actors, writers, directors, and producers were ‘blacklisted’, effectively halting their careers and forcing them to leave the US if they wanted to continue working. It was a dark stain on America’s history and was compared to a witch-hunt when a mere accusation was taken as proof of guilt.

In a string of high-profile investigations, known as the Army–McCarthy Hearings, the United States Senate’s Subcommittee on Investigations stepped in to weigh conflicting accusations between the US Army and the rampantly right-wing Senator Joseph McCarthy. This was a turning point that marked the fall of McCarthyism.

The fulcrum on which things were seen to change was when the Chief Counsel for the Army stood up to the hysterical Senator and calmly said to McCarthy, “you’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?” The man who said those famous words, and so precipitated McCarthy’s decline into disgrace, was none other than Joseph N. Welch.

Turns out that Welch is a fine actor and his pivotal portrayal of the open-minded Judge Weaver is pitch-perfect throughout. Though it was said that he couldn’t manage to walk and talk at the same time and could only deliver his lines convincingly when seated. So, the script was adapted accordingly.

James Stewart had no such difficulty and gives a winning performance among a near-perfect cast. His performance is what keeps the film eminently watchable, lightening the mood which could’ve easily become rather dark. He plays Paul Biegler (the fictional equivalent of John Voelker), who we first meet him as he returns from a fishing trip, stuffing his catch into a refrigerator already crammed with fish and little else.

The house he lives in paints a portrait of a complex fellow living the simple life. It’s modestly furnished, with shelves piled high with law journals and classic jazz records. The wallpaper is not of the trendy 1950s ‘atomic’ patterns but has a folk-art vibe with floral and avian motifs, indicating he is a down to earth man of the people. Perhaps a man out of step with the times.

The attention to detail here is impressive. I’m not sure how much is down to the great production designer, Boris Leven, who would win an Academy Award for the next film he worked on, West Side Story (1961), and go on to be nominated for his fantastic design on The Andromeda Strain (1971). He may have had a hand in selecting the props, but the house itself was already perfect. It is was really John Voelker’s house when he lived in Ishpeming!

In pursuit of authenticity, Preminger decided to shoot the film entirely on location along the Lake Superior coastal area of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where the original events that inspired Voelker’s novel actually unfolded. Most of the filming took place in Ishpeming and Marquette and the extras, including the jurors, were all from the local communities. The trial scenes are all shot in the County Courthouse. The tavern where the murder takes place, although not the actual ‘Lumberjack’s Tavern’ is in the same lakeside resort of Thunder Bay.

Preminger capitalises on James Stewart’s popular appeal as a likeable ‘average man’. The audience’s sympathies lie with Biegler and we’re rooting for the left of centre, jazz-obsessed attorney to succeed, even when we have grave doubts about the character of his defendant. Stewart plays him as affable, distracted and slightly bumbling, a familiar sort of Stewart role that, part-way through we realise is an act intended to put his big-city lawyer opponents off their guard…

Stewart had just turned 50 so was actively seeking more challenging and complex roles that would open up opportunities for him as an older character actor. Here he’s aided by his legal team made up of his alcoholic mentor Parnell (Arthur O’Connell) and unpaid secretary Maida (Eve Arden).

After James Stewart, Arden was arguably the biggest star on the bill, having appeared in more than 50 feature films before transitioning to the new format of television sitcom as the titular teacher in Our Miss Brooks (1952-56) and then starring in all 26 episodes of her own popular sitcom The Eve Arden Show (1957-58). This experience in comedy is evident in the good-natured banter between Maida and Biegler, providing another much-needed element that lightens the tone of what could’ve become a sordid and harrowing story.

The prosecution team is made up of the local District Attorney Mitch Lodwick (Brooks West, who was Eve Arden’s husband and producer of her show), who has brought in reinforcement in the form of Claude Dancer from Attorney General’s office (George C. Scott, in only his second big-screen role). Lodwick is clearly a little out of his depth in such a case.

On the surface, it looks to be a straightforward trial to which he expects a be cut-and-dried ‘guilty’ verdict. But also knows that his friend, Biegler, is a cleverer lawyer than he pretends to be and may well have a surprise up his sleeve. In contrast, Dancer is an aggressive, point-scoring prosecutor who, without knowing Biegler, is initially taken in by his opponent’s faux naïveté.

Lt. Frederick Manion (newcomer, Ben Gazzara) is the seemingly indefensible defendant who we know from the outset did, indeed, kill tavern owner, Barney Quill. He claims, though, that he has no recollection of the actual shooting, which he perpetrated after his wife Laura (Lee Remick) claimed that Quill had raped her. It’s unclear whether his claim is genuine, or if he has been coached by Biegler to say the right thing. This kind of ambiguity runs through the whole film and is an effective narrative hook that keeps the viewer guessing until the end.

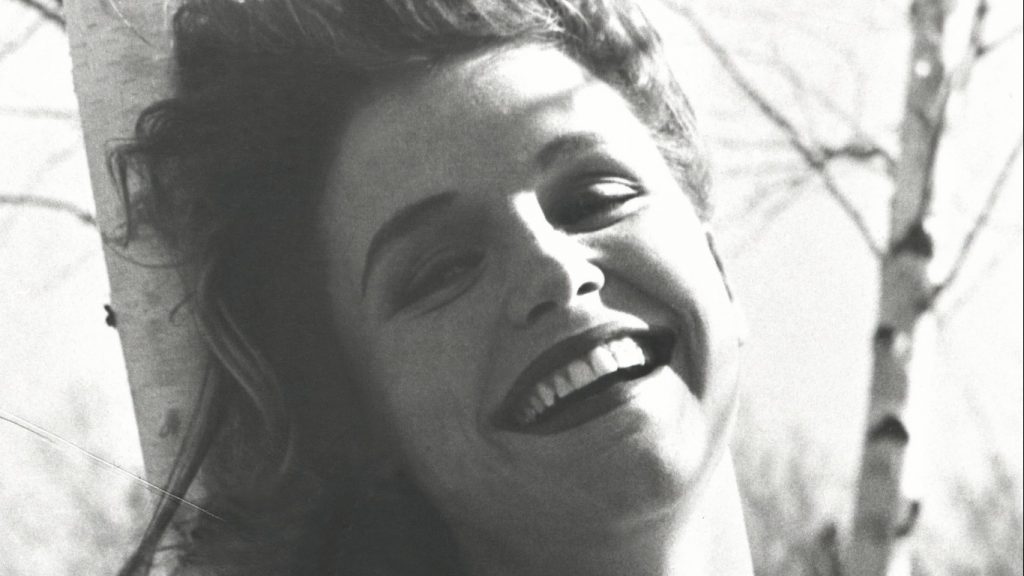

Make no mistake, although it’s Lt. Manion in the dock for murder, his wife Laura is also on trial and certainly judged for her fun-loving ‘unladylike’ reputation. The young Lee Remick is excellent here in an early role that marks her transition from supporting roles to leads. She plays Laura as easy-going, likeable, yet morally questionable.

She almost fits the bill as a femme fatale, but we’re never sure how scheming she might really be as she flirts with Biegler. It becomes clear that her marriage is far from idyllic and she and Frederick were already having relationship problems. There’s even some doubt as to whether her bruises were due to the assault by Quill or her husband’s reaction when he suspects her complicity…

Part of Dancer’s prosecution narrative is that Laura had dressed provocatively. He infers that the stance required for her play pinball in the tavern was calculated to show off a woman’s curves. This is added to the fact that she often went ‘bare-legged’, wearing a tight skirt and sweater and, what’s more, habitually went without a girdle.

Well, he implies that the murdered Quill, was acting in an understandable, manly way and it wasn’t his fault that he assaulted her and then got shot by her husband. Obviously, her attractiveness and attire were to blame. Surely, her rape and the rapist’s murder were both her fault, weren’t they? And the lieutenant deserves to be convicted if only because he had married such a floozy and not controlled her properly?

Unfortunately, this attitude was pervasive in the ’50s and, of course, many a lawyer would use it to sway opinion, often despite any hard evidence being offered. George C. Scott plays his part well, exploiting his strikingly sloping nose and jutting chin to invade the personal space of those who take the stand, particularly the women, Laura and a later a ‘make-or-break’ witness with an undisclosed relationship to Quill, Mary Pilant (Kathryn Grant). Grant, who I remember best as Princess Parisa in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), had just become better known as Kathryn Crosby, having married Bing and was soon to ‘retire’ from her promising acting career.

One can imagine that, for the time, the film’s content would be contentious. Using the word ‘panties’ was problematic enough, so dialogue that frankly addressed rape, its definition and how it can be medically evidenced was sure to fall foul of the Motion Picture Association of America Production Code, better known as the Hays Code.

It wasn’t just the use of language. Jazz legend Duke Ellington composed the score for the film, which has earned a reputation as one of the best jazz soundtracks of all time. In one scene set in a swinging ‘juke-joint’, James Stewart joins the Duke at the piano. At the time, though, merely having a white actor sit and play jazz with a black musician was an edgy thing to do. Remember, this was just a couple of years ahead of terrible and tragic race riots that plagued the US throughout the 1960s.

Having seen his homeland suffer under Nazi rule and, as a Jew, what the erosion of freedom can lead to, Preminger was a stalwart of free speech. He’d already had a few run-ins with the Code, most notably for his film The Moon is Blue (1953), a comedy-drama over which he defied the censors by famously refusing to cut just 15 seconds of dialogue that demonstrated “an unacceptably light attitude towards seduction, illicit sex, chastity, and virginity.” It has been suggested that it was the words “virgin”, “seduce”, “mistress”, and “pregnant” that caused the most trouble. Well, they do kind of form a narrative of their own!

Without approval of the MPA, no distributor would take the movie until the offensive dialogue had been removed. Did Preminger remove the offending words? He did not. Instead, he lodged an official appeal against the MPA’s decision, which aggravated them all the more. But then he turned it all to his own advantage, formed an independent distribution company and released the film himself, riding the wave of publicity generated by the controversy. It was a big box office hit and made his name as a maverick film director, his notoriety rivalling that other envelope pusher, Alfred Hitchcock.

By the time he made Anatomy of a Murder, the Hays Code was rapidly losing sway over the Hollywood studio system, in no small part due to Billy Wilder’s deliberate challenge thrown down by his classic courtroom drama two years earlier, Witness for the Prosecution, which set a sort of precedent, if you like.

Wilder had deliberately targeted the core guidelines of the Code and openly transgressed them whilst making a very successful mystery thriller. Unlike Witness for the Prosecution, which was based on a play written by Agatha Christie and so had an audacious twist in the final act, Anatomy of a Murder never resorts to such sensationalism in its plot. It stays well within the bounds of believability whilst masterfully maintaining its grip of suspense…

By broaching subjects of rape, murder and mental illness, Anatomy of a Murder still caused enough controversy with dialogue that included words previously unheard in cinema, such as “spermatogenesis”. The censors finally approved it uncut, but it still provoked the ire of the Catholic Legion of Decency who lobbied for its ban.

The Mayor of Chicago, Richard J. Daley, invoked police powers to prevent the film’s distribution in his city, but Preminger took him to the federal court and the mayor’s objections were overturned as the judge deemed that the use of such authentic clinical language was appropriate within the film’s context of showing the legal process of a trial. I wonder if the legal prestige of the original novel’s author and the on-screen presence of Joseph N. Welch had any influence over that decision?

Usually, crime films based on true scenarios are too unsavoury and unpleasant to be enjoyed as entertainment. They may be worthy, they can be challenging, but unless handled as cleverly as this, are certainly no fun. Anatomy of a Murder may have set the bar for the kind of crime series so popular today. TV dramas like the CSI franchise, Bones, Body of Evidence, and Silent Witness, which often deal with some truly unpleasant and gruesome crimes and follow a similar procedural template, but at least attempt to entertain with elements of suspense and an array of interesting characters.

It’s certainly, the most entertaining film I’ve seen about rape and murder. It’s perfectly paced, Sam Leavitt’s cinematography is starkly beautiful, the sound design subtle and innovative, Ellington’s musical score a classic in its own right, the dialogue is naturalistic yet sparky, the finale is astutely ambiguous, and the performances leading up to it are all consummate… to say nothing of the dog!

director: Otto Preminger.

writer: Wendell Mayes (based on the novel by Robert Traver).

starring: James Stewart, Lee Remick, Ben Gazzara, Arthur O’Connell, Eve Arden, Kathryn Grant & George C. Scott.