HIM (2025)

A young athlete descends into a world of terror when he's invited to train with a legendary champion whose charisma curdles into something darker.

A young athlete descends into a world of terror when he's invited to train with a legendary champion whose charisma curdles into something darker.

Dreams, desires, and hopes—we all possess them. They start at a young age and are usually brought upon by people whom one looks up to, like members of their family—a father, mother, or sibling perhaps. Sometimes it’s through inspiration, such as a form of art, like painting or music, or even something performative, such as a sport. Sometimes, it can be a culmination of the two—a family member has an affinity towards X, and in turn, their kin or sibling picks up on it, too.

Some people’s dreams are simple, like mine: I’m an oil painter at heart, and my dream is to create work and share it with others through exhibitions at galleries willing to showcase it—nothing more. I have no interest in the glitz and glamor, the interviews in art magazines that people who shop at stores like Blick or Michael’s read, or the large circle of “friends” that includes trust fund kids and celebrities who indulge in this peculiar cultural pastime.

While I’m confident in my aspirations, I can’t speak for everyone else. There are plenty of people who desire notoriety and the gilded opulence that comes with it. Some are even prepared to do anything necessary to achieve that goal. This brings me to Justin Tipping’s latest film, HIM—a psychological, occultist horror film centered on chasing one’s dreams and the sacrifices one is willing to make to obtain them.

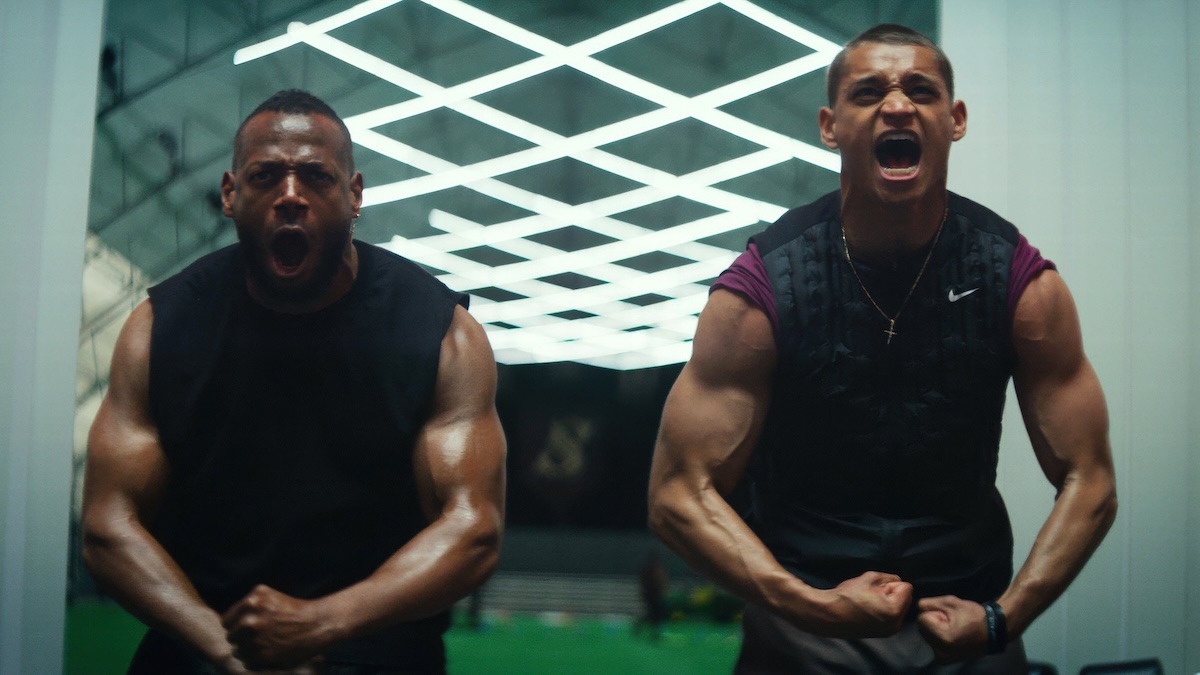

HIM begins with an adolescent, Cameron Cade (uncredited), sitting in front of a television, watching football in the living room of his parents’ home. His father cheers for the family’s favourite team and their star player, Isaiah White (Marlon Wayans). Young Cameron is in love with this player and aspires to play football one day, to which his father preaches inspirational words into his ear ever so intensely after their team won the game—words that will inspire Cameron to become the best athlete he can be.

What follows is one of my most despised practices within the entire cinematic medium: the montage. I find its use to be rather lazy. Most filmmakers rely on it as a crutch to cover a long measurement of temporal occurrences without having to dedicate the appropriate time to properly flesh it out pragmatically. There are exceptions to its use, such as Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980), where he uses the montage to cover a significant moment in Jake LaMotta’s life that isn’t related to his passion for boxing: his wedding, honeymoon, and post-matrimony days of his newly evolved relationship with a minor.

While this element in Raging Bull’s screenplay facilitates its character study and biopic genre classification, I do not consider it the most important element within its screenplay; rather, it’s a complementary one—it doesn’t detract from nor undermine the importance of the screenplay’s meat. The same can be said with Tipping’s use of the montage in HIM, as the meat of this film is one being at the cusp of obtaining a dream and what they would be willing to do to obtain it.

In HIM, the montage is used to show adult Cameron (Tyriq Withers) training to be able to be in a position that is near that cusp while simultaneously showing blips of Isaiah’s career that are occurring simultaneously via the use of avant-garde editing techniques to allure and fixate the viewer’s gaze to the screen. I will admit, the editing and visual direction are easily the best parts of the film. It’s odd, as many who have seen HIM have criticised it for its visuals and editing being indicative of something akin to practices used in music videos, to which I agree to a degree; however, their subsequent remarks state that the employment of said practices has no cinematic value. This I do not agree with.

HIM does have a music video-style identity to its editing that I feel is approached cinematically. There are moments where the tempo of the score paired with a specific scene matches the tempo of the movement of its characters and/or editing, yet the shots are appropriately framed and intertwine with editing that is akin to ones employed in the various new wave movements throughout cinema history, such as static tracking cuts, interesting and unconventional transitions, secondary imagery appearing and disappearing, and what have you, along with some advancements in the avant-garde, such as using the editing and control of the camera to evoke the character in focus’ current emotional state, or even something entirely fresh, such as cuts shot entirely in x-ray vision.

Others may have disdain towards HIM’s visuals and editing, but I was entertained. Well, for the most part. There’s an element in its visuals that I felt was immensely lacking, and that was its leaning towards occultism. HIM’s premise of sacrifice for fantasy fulfilment aligns with the idea of the socioeconomic elite partaking in occultist practices, à la Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999); however, it only exists as aesthetics.

There is some pagan imagery, if that, as well as the unicursal hexagram used in Thelema—a Western esoteric socio-spiritual occultist philosophy by Aleister Crowley—and some unknown, bizarre, and seemingly custom occultist imagery, yet it doesn’t go farther past what is picked up via the audience’s optics. There’s never any insight into the occult practices used in the upper echelons of the film’s world’s socioeconomic hierarchy, nor the overwhelming feeling of stumbling into a world beyond one’s comprehension, like in Eyes Wide Shut. It’s all flash and no substance.

Unfortunately, that happens to be the case for the entire film. HIM is all flash and no substance. It doesn’t start off that way, as the imagery and what transpires throughout the first act are intriguing; however, both lose their lustre once the film’s direction begins to meander about. There’s no meat, no direction in its screenplay, nor themes that the audience can latch onto.

HIM feels like a freshman film that has little to no confidence in what it’s trying to do, so it instead relies on its high budget to persuade someone adept in cinematic visuals, in this case Jordan Peele, to be a producer of the film and use their prowess to hide its lack of confidence with mostly alluring imagery. In fact, had it not been for Peele’s prowess, HIM would have been the worst film of the year for me, and I’m not being hyperbolic.

Tipping wears his inspirations on his sleeve—Satoshi kon’s Perfect Blue (1997), Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010), Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, and Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain (1973)—yet doesn’t present exactly what he wants to do. Cameron gets the chance of a lifetime to train with his idol at his private abode, which is equipped with its own football field, but he spends most of his time there.

In an attempt to facilitate its themes of sacrifice and occultist foundation, during Cameron’s five-day training bootcamp of sorts, weird things begin to happen, and we’re unsure if they’re real or not, whilst simultaneously real things do occur that are abnormal and unsettling to him. Whether the imagery that is presented is real or not, they’re approached in a highly edgy manner. At points, the events that occur feel as edgy as the ones that transpire in Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn (2023), such as when, to show the profundity of his psychopathy, Fennell writes Oliver Quick to lick semen off the bottom of a bathtub. Again, I’m not being hyperbolic. A lot of the occultist imagery used equates to hot, stylised flatulence, and nothing more.

This film gallivants about without a care in the world until its end, where Tipping includes contrived conflict and a contrived resolution, which the latter nearly contradicts the purpose of the entire film. I’ve spent most of this write-up doing my absolute best to release faecal matter all over it, but I have to state that it has the potential to be such an interesting piece on how subsets of cultural elites groom those with prowess to become the best, which in turn begs the question if they’ve really earned their success or not.

This reflection hit close to home, as I wondered if my placement in the New York Academy of Art was fully earned by myself, as one of my professors, who was also one of my mentors, was friends with the dean of the NYAA, which landed me an interview with him before I was accepted into the school. So, that’s something that HIM has going for it outside of its editing and non-occultist visual direction.

Then there is the acting prowess of both Withers and Wayans, who both do a pretty good job with their performances in this film. If anything, I feel bad for Wayans, as this has been, to my knowledge, his first non-comedic role since Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream (2000). He does his best to play a severely dedicated, almost cultishly obsessed football athlete whose characterisation tends to be unhinged, facilitating the film’s fine balance of comedy and horror. He does a good job here, but it’s unfortunately tied to something as aimless as this film.

While it had promise in the front half, the latter half proves to be unfocused and edgy. Tipping shows that he has no confidence as a filmmaker and chooses to make a film that relies on visuals and musical score as a means of distraction from how atrocious the screenplay for HIM is. In art school, I was taught that if I were going to explain the artistic theory behind my work, I’d need to do it within an elevator pitch’s worth of time, as gallery owners and collectors alike rarely want to hear an artistic diatribe about one’s own work, nor do they have time to. Well, if I had to approach my thoughts on HIM in that same manner, it would be as such.

USA | 2025 | 96 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Justin Tipping.

writers: Skip Bronkie, Zack Akers & Justin Tipping.

starring: Marlon Wayans, Tyriq Withers, Julia Fox, Tim Heidecker, Jim Jefferies, Naomi Grossman, Maurice Greene & Norman Towns.