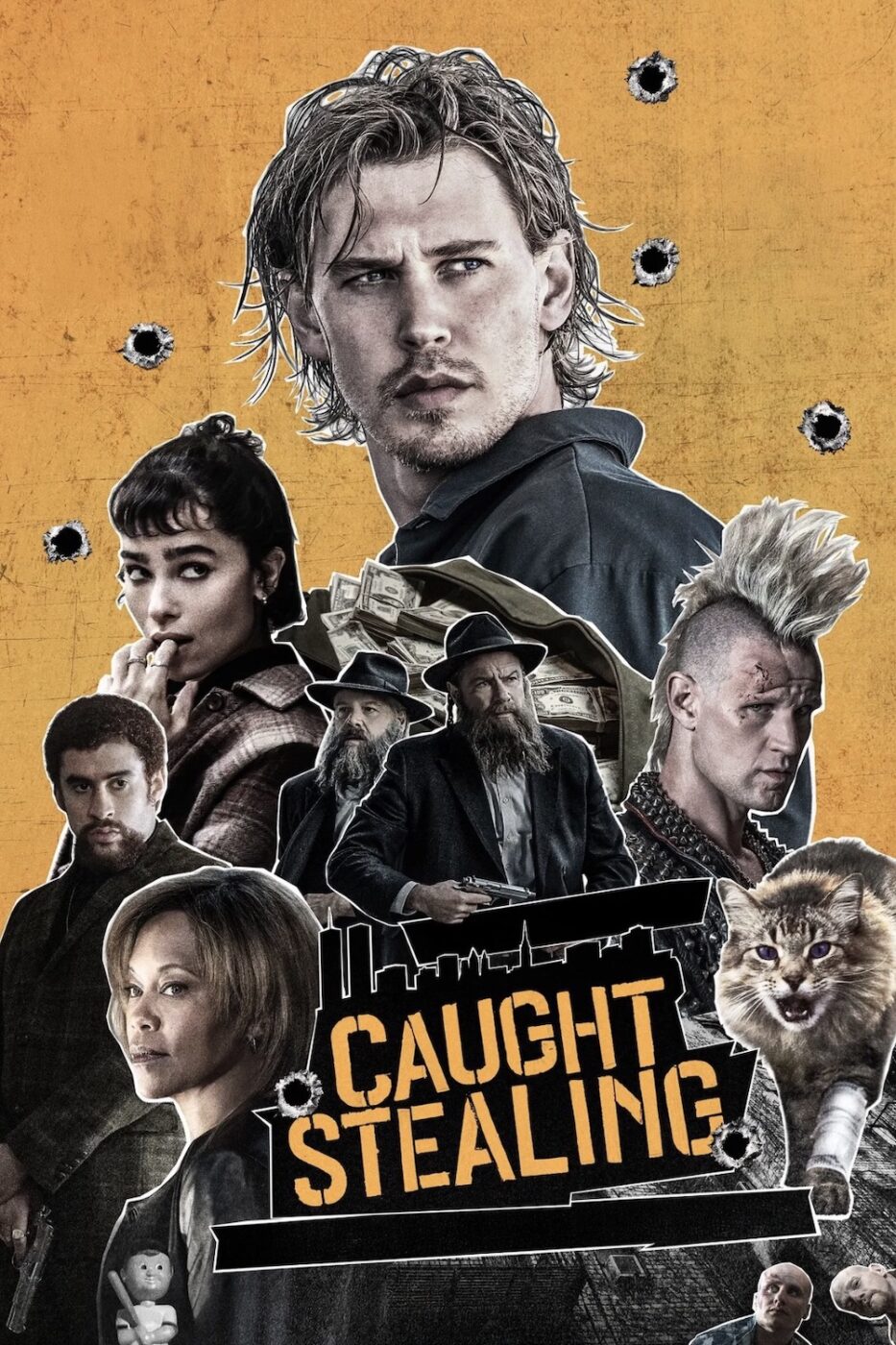

CAUGHT STEALING (2025)

A burned-out ex-baseball player finds himself embroiled in a dangerous struggle for survival amidst the criminal underbelly of 1990s New York City...

A burned-out ex-baseball player finds himself embroiled in a dangerous struggle for survival amidst the criminal underbelly of 1990s New York City...

Unless you’ve been living under a rock on an uncharted island, you should be familiar with the work of Darren Aronofsky. His career’s spanned many decades, beginning in the early-1990s with the release of a slew of short films before he refined his focus and released his first major film, Pi (1998). Aronofsky’s debut showed elements of his inspirations, mainly the late David Lynch’s surrealist body horror masterwork, Eraserhead (1977), and the films subsequently released within the cyberpunk genre—a subgenre in underground cinema whose origins are rooted in low-budget 1980s Japanese filmmaking—that influenced them.

The Japanese cyberpunk genre had a focus on urban decay, economic famine, corporate apathy and avarice, and the synthesis of flesh and machine. Films such as Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) discussed how humanity’s advancements in science and technology are fuelled by their repressed animalistic elements within their unconscious, and how this insatiable fervour would lead to humankind’s demise—a focus similar to that discussed by David Cronenberg in his body horror masterpiece Videodrome (1983).

While Shozin Fukui’s film 964 Pinocchio (1991) focused on how these very same advancements lead to dehumanisation—a loss of cognition and autonomy—which corporations would then use for capital, whilst those who eat at the same table as those who have been lobotomised (I’m using that term perversely) proceed to use them for their own satiation—an avant-garde representation of the cyclical economic relationship between big business and its patrons.

Based on the genre’s defining thematic elements, I’d argue that Pi is a part of the cyberpunk genre, given its low-budget, avant-garde, and sometimes guerrilla approach to filmmaking, as well as its focus on the amalgamation of flesh and technology being used as a means for X. In this case, it presents a narrative focused on how humanity can further its evolution through technological integration—a focus similar to Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell (1995).

As someone who’s been watching Aronofsky’s work since Requiem for a Dream (2000), it’s his modus operandi to wear his specific influences on the sleeves of whatever film he’s working on. Black Swan (2008) is another precise example of this, although the film seemingly bites too much from his inspirations, which essentially makes it a live-action remake of Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue (1997), except the protagonist is a ballet dancer instead of a pop idol and actor. Oh, and its themes are different, I suppose.

I’m happy to report that Aronofsky’s Caught Stealing doesn’t do anything egregious like “unintentional plagiarism.” No, this time around, he builds a narrative off what seems to be a favourite genre of his: film noir. Caught Stealing is a frenetic, appropriately violent—the type that one can feel while viewing—and, most importantly, a titillating noir indicative of the same musings and literary practices of the 1940s but placed in ’90s Giuliani-run New York.

Hank Thompson (Austin Butler) is a forcibly retired baseball player who could have gone to the big leagues had it not been for an absurd moment that occurred in his life; he’s now an alcoholic. One night, after he and Yvonne (Zoe Kravitz)—a woman Hank’s has been dating for a short while, whom he has feelings for—return to his place, they find Hank’s friend, Russ (Matt Smith), leaving his cat, Bud (Tonic), at his doorstep, as he has to catch a plane to London to visit his father, who just had a stroke.

Unbeknownst to Hank, Russ has evidently involved him in an intricate crime scheme, for which Russ is the sole person responsible for paying everyone involved, such as corrupt members of the NYPD, the Russian mafia, the Puerto Rican mob, and the Jewish mafia. No matter which road Hank chooses to take, he finds himself falling deeper and deeper within this web of criminality.

Caught Stealing embodies the essence of noir, emphasising archetypal characterisations, elements of mystery in an attempt to figure out who did what and who is worth trusting, themes of absurdity and fatalism, and the intricacies of racketeering. However, it also presents choices that challenge the conventions of the genre. These acts of literary defiance are what make Caught Stealing stand out amongst its genre-specific contemporaries—it takes risks with the roles of its characters; no one is safe.

As a period piece, Caught Stealing is highly convincing. The streets of New York in this film vividly reflect the urban decay of the era; landmarks like Shea Stadium are present, while music from artists such as Smash Mouth, Madonna, Spin Doctors, Semisonic, and Meredith Brooks fills its temporally emulated ethos. Political rhetoric within bars, subways, and in front of pavement newspaper stands hovers over social commentary rants amidst a big moment for the Giants (baseball) in the playoffs.

Even its cinematography, courtesy of Matthew Libatique, the cinematographer for films such as Requiem for a Dream, Black Swan, mother! (2017), The Whale (2022), and Don’t Worry Darling (2022), is galvanising. His compositional framing is well-executed, varied, and not mechanically arranged; complementary colours are used to further allure the viewers’ attention to the screen; and the Instagram-like visual filters used to be reminiscent of the time are completely omitted—-thank goodness!

Oh! How could I forget Austin Butler’s performance in this film? It’s easily his best performance to date. He has this approach reminiscent of Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, and Robert De Niro, in that he uses his physicality when he acts, whether strictly in the face or with his entire body. This proficiency, absent in most of his contemporaries, allows Butler to evoke feelings of both emotional and psychological frailty and the eventual frenzy that subsequently occurs once tension comes to a head, while turning so-so dialogue into gilded oration, just like the actors I mentioned previously. Hell, Butler properly embodies every facet that encompasses the characters he plays, emotional weight and all. He’s an actor I’d like to see in more films, as I find him to be one of the best in the field currently.

Outside of Yvonne’s slightly underdeveloped character, Kravitz’s acting at times looking expressionless in the eyes, and some conveniences that occur in the screenplay, my biggest gripe is how Hank’s dream scenarios are handled. In analytical psychology, dreams are seen as a means into the unconscious mind. Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud has famously said, “The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind,” exposing hidden desires and conflicts to the dreamer that are repressed in the waking world via a series of obscured representations, often associated with their sexual and/or aggressive instincts.

Swiss psychoanalyst Carl G. Jung—a follower and collaborator of Freud—believed that dreams serve as a means of communication between the conscious and unconscious realms of the human psyche. He proposed that dreams are laden with symbols that unveil hidden truths about a person’s psyche and facilitate personal growth. This makes dream interpretation a vital therapeutic tool for exploring unresolved issues and gaining insights into one’s emotional and psychological journey toward wholeness—a process referred to as individuation.

In films that utilise these psychoanalytical elements, they’re often presented in a surreal manner, sometimes darkly, à la the work of Lynch, who would often use the teachings and theories of both prominent figures in analytical psychology in his work, though he would focus on a singular figure’s teachings for a singular film. Their imagery is usually varied, twisting, turning, and metamorphosing into distinct yet obscured ways, sometimes coalescing with other elements or existing amongst them. The chromatic presentation varies, too, but their tonality can be volatile, turning any dream into a nightmare and sometimes back again, potentially repeating the process.

Based on this, the use of surrealist imagery to evoke the profundity of dreams in cinema makes for the most compelling moments within a film, if the film isn’t already based in it. Unfortunately, that isn’t the case for Caught Stealing. Instead, Charlie Huston, the author of the novel that this film is based on, and Aronofsky present Hank’s dreams as a flashback, one concerning a moment of cold indifference that he has been repressing since it occurred.

There’s nothing surreal about how it’s presented: no altering of characters or the existence of symbols, nothing. They’re simply flashbacks, specifically the same one just cut up into portions. Each time Hank falls asleep, we’re given the next serving, but it’s obvious to me from the first dream as to what had occurred that shaped Hank into who he is at the start of this film.

Personally, I find it a bit surprising and underwhelming that Aronofsky went this route, as he treats the profundity of dreams as a mere device to relay the most comprehensible repressed trauma I have ever seen. Anything repressed that comes up to one’s conscious mind isn’t always effortless to handle. This is why it’s imperative that one should go through the process of individuation to help strengthen their egos to better handle whatever resides in their shadow. Dreams abscond with details or the entirety of one’s trauma.

He has no issue presenting films, such as Black Swan and mother!, in surrealist imagery; however, Caught Stealing doesn’t go this route. Was it to remain faithful to Charlie Huston’s novel? I don’t believe that a screen adaptation of a novel needs to adhere to its source material entirely, as not all literary elements within a novel can properly translate over to the silver screen. Appropriate adjustments must be made to better suit the medium.

Was it to prevent the film’s imagery from suffusing out of film noir? If so, shame on Aronofsky. Film noir became dormant for many years due to how trite and repetitive the genre became. Risks weren’t taken, and the genre became formulaic. What was the point of seeing X film when its structure, characterisations, and thematic identity mirrored a classic revered within the genre?

Can you imagine an entry into the genre of film noir where, for one to figure out the dark past of its protagonist, one must have a keen sense of visual analytics and a solid understanding of analytical psychological theories concerning dreams and the human psyche? I can, as Lynch certainly did exactly that with films like Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Drive (2001), and Inland Empire (2006). He’s been inspired by his work before, so I can’t comprehend his disinclination with this film.

That doesn’t necessarily mean I think Aronofsky should go full Lynchian with the dream sequences; that’s not what I’m trying to say. What I am trying to say is that there’s a literalness to Hank’s dream sequences that I find evocative of torpor. They’re the most underdeveloped portions of the screenplay, especially when contrasted against how well-written the rest of the film is, especially how it both plays into and defies film noir conventions.

It doesn’t matter. Whatever the reason, it holds Caught Stealing back from being a more fully realised version of itself. However, despite this, it’s still one hell of a watch. Watching this film made me question the quality of other contributions to the medium that are also meant to be titillating but fail in any attempt to woo the audience, and I’m speaking about those who aren’t satiated by the watered-down, lifeless, semi-icy taste of Kirkland vanilla ice cream. Films that follow a corporate template of the “good guys” always winning and the villains having the same plans for world domination or the extinction of the human race, or life within the universe if the filmmaker really wants to get spicy!

I’m referring to big film companies, like Disney, with their contributions to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. It’s their adherence to their banal formula that prevented Sam Raimi from creating a version of Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022) that was heavily Lovecraftian and indicative of his filmmaking style, or from The Fantastic Four: First Steps (2025) from fleshing out its existential philosophical thematic identity, as well as its other cinematic elements, such as narrative and editing, for it to not be the second most abhorrent piece of filmmaking I’ve seen this year—the first being Rich Lee’s Amazon-funded remake of War of the Worlds (2025).

Big-wig film companies need to get their rear ends to the cinema, watch Aronofsky’s latest film, and take notes! Although, on second thought, they’re too blinded by capital to understand the elements that encompass a well-executed, thrilling, and engrossing cinematic experience, like Caught Stealing.

USA | 2025 | 107 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • SPANISH • YIDDISH

director: Darren Aronofsky.

writer: Charlie Huston (based on his novel).

starring: Austin Butler, Regina King, Zoë Kravitz, Matt Smith, Liev Schreiber, Vincent D’Onofrio, Benito Martínez Ocasio, Griffin Dunne & Carol Kane.