ERASERHEAD (1977)

Henry Spencer tries to survive his industrial environment, his angry girlfriend, and the unbearable screams of his newly born mutant child.

Henry Spencer tries to survive his industrial environment, his angry girlfriend, and the unbearable screams of his newly born mutant child.

Eraserhead can be read in so many different ways, and this helps maintain its timeless appeal. So much has been written about David Lynch’s extraordinary debut feature that it’s difficult to say anything new. Yet the film itself still appears so fresh and unique it remains difficult to categorise. Usually, it gets placed in the horror genre, and that’s probably the best place for it.

Some of the scariest moments I’ve seen on screen are in Lynch films, but Eraserhead isn’t really one of those. It’s also (straight)-laced with the bleakest of black humour and one of very few films that made me laugh out loud in a cinema. Though I think calling it a comedy is a bit of a stretch!

It’s these moments of observational humour (delivered with absolutely perfect timing) that make the astonishingly disturbing sequences all the more horrific. The final act is often described as so nauseatingly intense as to be unwatchable. It doesn’t get any easier with repeat viewings…

Re-watching David Lynch’s debut after at least a couple of decades was a revelation. So much of his visual style is right there from the start. It’s saturated with his obsessions and the recurring motifs that have come to define what it is to be ‘Lynchian’. Now, after the third season of Twin Peaks (2017), it can clearly be seen that the story began here.

The nods to Monroe and Kennedy can just about be glimpsed. If you’re paying attention. The nuclear bomb is explicitly referenced. A dysfunctional relationship between parent and child runs through it. And it’s here that we first enter the Black Lodge with its distinctive zig-zag flooring. Lynch’s ensuing career seems to be one huge sequel!

I can clearly recall the first time I watched Eraserhead after hearing about it for a few years. I’d often spotted the striking image of Henry Spencer (Jack Nance), with his high hair, on T-shirts worn by people at the punk gigs I frequented. So, when it was billed at my college arts cinema, I was there.

It was sometime in the early 1980s and I’d never seen a film anything like it. After the blindingly bright final frame there’s a full seven seconds of darkness before David Lynch’s name appears. I thought my mind had snapped! It changed my whole expectations of what cinema could achieve.

This was no ordinary art film. It was filmed art.

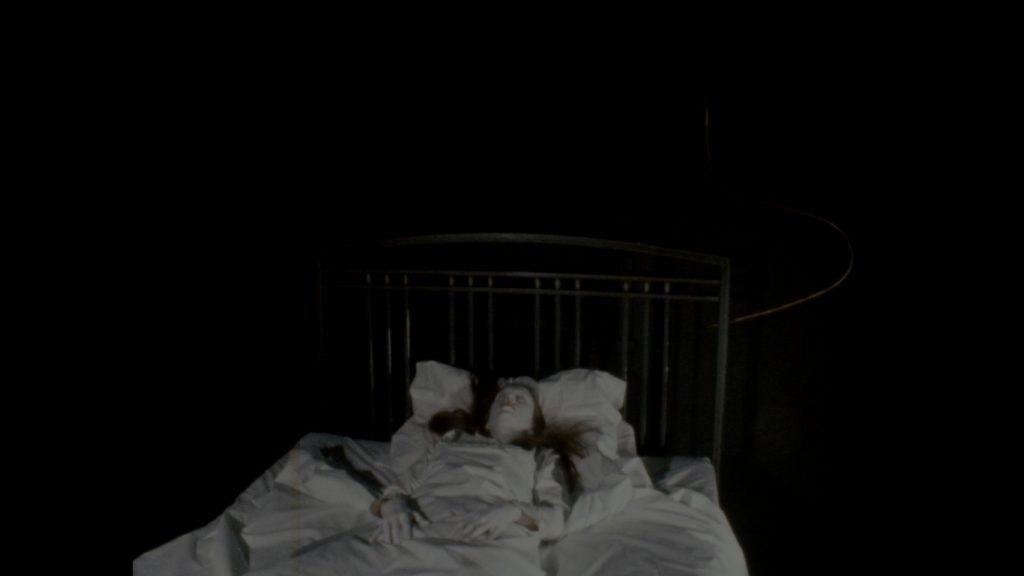

The plot is so simple that it’s almost not there. The entire script was just 22-pages long. But the scant story is hypnotically absorbing from the start as we’re assaulted by disconcerting imagery accompanied by deep subsonic thrumming and white noise. The title appears in darkness: Eraserhead. What could that possibly be about? Then the superimposed face of a man drifts upward across what appears to be a space scene, with a planet hanging among dust-like stars.

The man looks perturbed. He opens his mouth in a silent scream and something issues forth. It’s a long, organic shape that looks like a hybrid of a giant spermatozoa and a foetus. The camera tracks past the face hanging in space and onto the dark surface of the planet. There’s a shack with a hole in its roof. We enter to find a skinny, scarred man sitting by a window. He’s the operator of some sort of signal box with a set of levers before him. We later deduce these levers control the destiny of the film’s protagonist, which like our own sanity, is about to be derailed.

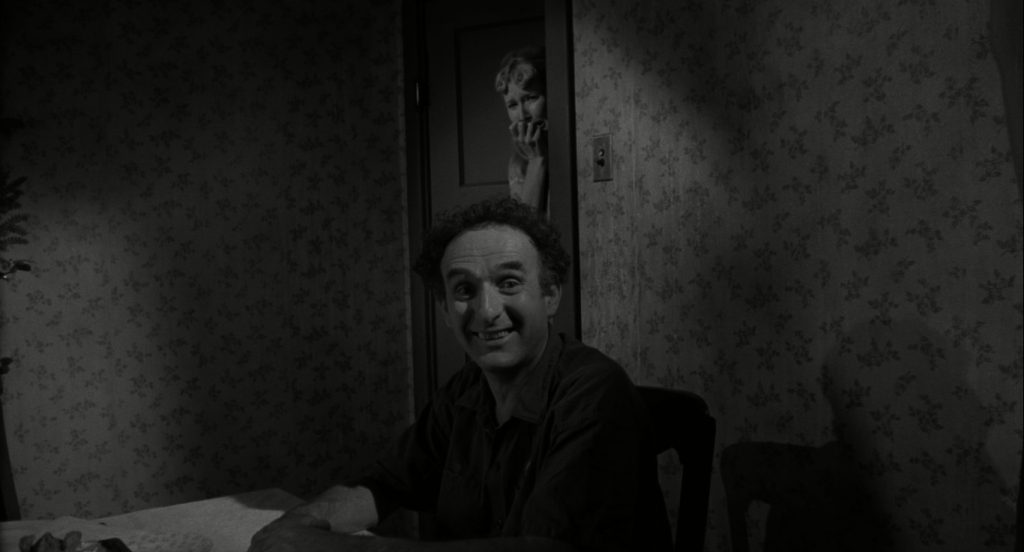

The film opens with the lone figure of Henry walking through some desolate industrial wasteland. He wears a dark suit, with trouser cuffs too short and hair standing on end, as if electrified. He looks awkward and small wandering past the grey facades of seemingly derelict warehouses to his apartment block where the hall is carpeted with the striking zig-zag design and the elevator doors leave a long, ominous pause before closing on this vulnerable man adrift.

Each change of environment is accompanied by its own unique, atonal drone. In the hands of many a director, these scenes would’ve been dull and boring. Lynch makes them dreamlike and absorbing. They fascinate and lodge themselves in memory as if directly addressing the subconscious. And that’s, literally, just the beginning.

Henry, it seems, had a dalliance with Mary (Charlotte Stewart). From the torn photo he’s kept, we gather it did not end happily ever after. Yet he hasn’t discarded the two halves of her picture and accepts an invitation to visit her at her parents’ home for dinner.

The whole scene rings true for anyone who has experienced similar social anxiety and it takes the ‘meet-the-parents’ trope to a new level of awkward. Mary’s desperately jovial dad (Allen Joseph) enthuses over plumbing, the numbness of his left arm and a new type of artificial mini-chicken they’ll be serving.

Then, there’s the decidedly oddball mother (Jeanne Bates) who interrogates Henry about what transpired between him and Mary. She wants to know if they had “sexual intercourse” and gets so emotional about the subject that she can’t help but corner the young man and lick his face. It turns out that since he last saw Mary, she’s had a baby. Well, as Mary puts it, “they’re still not sure it is a baby!” and in the next sequence we find out what she meant by that!

Simply put, it’s a film that has to be seen. You’ll either love or hate it, but you must admire its creative confidence, audacious originality and distinctive disposition. There’s no other film like it! Well, actually, there may be a few, but I wasn’t aware of them when I first saw Eraserhead.

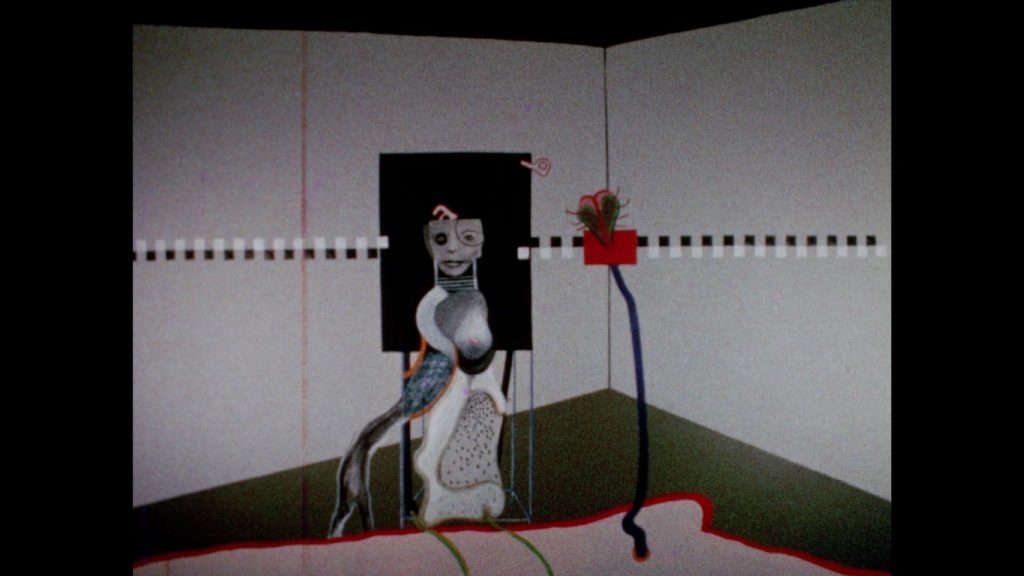

Often, it’s described as surreal and compared to the films of Salvador Dali and Louis Buñuel—Un Chien Andalou (1929) or L’Age d’Or (1930). But although Lynch embraces the absurd, I don’t think Eraserhead is surreal, at least not in the same sense. Sure, it deals with layered realities and the internal psychological landscape of the characters spills across the film’s consensus reality. But, for me, this is a step toward a deeper realism than most movies ever attempt.

Its forebears include the early works of Jan Švankmajer, though I dare say the Czech filmmaker’s later films may have, in turn, been influenced by Lynch—I’m thinking of Little Otik (2000), in particular. But to me, the obvious precursor is Jean Cocteau’s film debut Le Sang d’un Poète / Blood of a Poet (1930), and its follow-on features Orphée (1950) and Le Testament d’Orphée (1960). Having now seen Cocteau’s loose trilogy helps build an understanding of how to better appreciate Eraserhead…

Jean Cocteau was an artist who refused to be defined or constrained by any single medium. Just like David Lynch, he began his career as a visual artist before becoming better known as a designer, dramatist, poet, and film director. Apart from sharing visual resonance, and some visceral metaphor, both films deal with something intangible, yet intensely personal.

Eraserhead is so open to interpretation that it could mean almost anything. This is both its main strength and major flaw. But what it’s supposed to mean is pretty irrelevant. Like the work of many gifted songwriters, it has emotional authenticity without being particular to an individual experience.

Although expressed with blunt honesty, it’s use of universal symbols, archetypal motifs, and ambiguous metaphor makes it readily translatable to touchstones in the lives of others. Which means that, although its precise meaning is obfuscated, it can still make a deeply personal connection with the viewer. It becomes a suitably grim, modern fairy tale.

David Lynch has has summed it up simply as, “a dream of dark and troubling things,” and says that of all the many interpretations put forward by viewers and reviewers over the decades, none have hit the nail on the head. Not as far as his own intentions were concerned. He doesn’t think that diminishes its value in any respect, in fact, quite the contrary.

Possibly the most oft-repeated reading is that it’s his response to parenthood. Which is about the only interpretation he has strenuously denied. For me, it’s certainly about conception, and birthing. But not necessarily of an actual baby.

It’s about concept as much as conception. The creative commitment of bringing an idea into the world, a child, a painting, a movie. All things that others may judge you for, and more importantly, what one might use to judge oneself.

The baby in Eraserhead may well be an aspect of Henry’s self. His inner child perhaps, and maybe that’s why the seductive woman (Judith Roberts) across the hall from his apartment sees it in place of Henry in one key scene?

The film itself was conceived whilst David Lynch was living in a particularly rough neighbourhood of Philadelphia and reading some heavyweights of East European literature, like Franz Kafka. Kafka’s 1912 story Die Verwandlung / The Metamorphosis also fused realism with the fantastic as its everyman central character transforms into a man-sized cockroach and explores the darker aspects of human relationships.

Lynch was also reading Nicolai Gogol, who wrote absurdist metaphor about the human condition as well as the Gothic short story of 1835, Viy, which was filmed in several versions including Mario Bava’s free interpretation, The Mask of Satan (1960). Lynch has cited Bava as an important influence and included visual references to Kill, Baby …Kill! (1966) in Twin Peaks (1990-91).

He doesn’t recall actually writing the first draft of Eraserhead, but it did come about at the time he became a father, in 1968. Being a struggling artist living in a poor and often violent neighbourhood, there was some apprehension at the prospect of raising his daughter, Jennifer, who reputedly believes her birth did inspire the film’s central theme.

By the time he moved to Los Angeles to join the newly founded American Film Institute (AFI), in 1971, Lynch had the script and had already made a few shorts that prefigured much of the audio sculpture and visual symbolism he was about to develop in his first feature film. Eraserhead is, in fact, a student film!

The relentless, ‘dark ambient’ soundtrack is one of its most distinctive elements. He’d already collaborated with sound artist Alan Splet on the short film The Grandmother (1970) which mixed animation, sculpture and live action with expressionistic sound instead of dialogue. The result is truly disturbing and Lynch’s visuals were primarily driven by the sound design. Splet had also relocated to California and joined the AFI to study sound recording and editing.

Although the innovative score seems to come out of nowhere in cinematic terms, it’s another result of Lynch coming, not from a film, but an arts background. It follows the avant-garde explorations of the mid-1960s into what would become known as ‘concrete music’. Perhaps best exemplified by John Cage, A.M.M, and especially German experimental composer Karlheinz Stockhausen.

For those familiar with the score of Eraserhead, just have a listen to Stockhausen’s offerings from the mid-1960s, such as Mikrophonie, and his 1968 album Aus den sieben Tagen / From the Seven Days. Sequences from the track “Nachtmusik” evoke a strikingly similar nightmarish vibe to the sounds that merge industrial sonics with the elongate mewling of the baby during the film’s finale. Having said that, there’s no denying that the film’s soundtrack lends a unique atmosphere and was hugely influential on underground music of the early ’80s—groups like Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV.

After “flunking” his first year at the AFI, Lynch was coaxed back by his tutor, the influential Frank Daniel, who gave him free rein to use the undeveloped stable area of the mansion house where the film school was based. He was budgeted with a meagre grant on the basis of his script’s brevity that implied a short film of just 20-40 minute’s duration. To realise his feature-length vision, he knew he’d have to work hard with a very small cast and well-meaning crew.

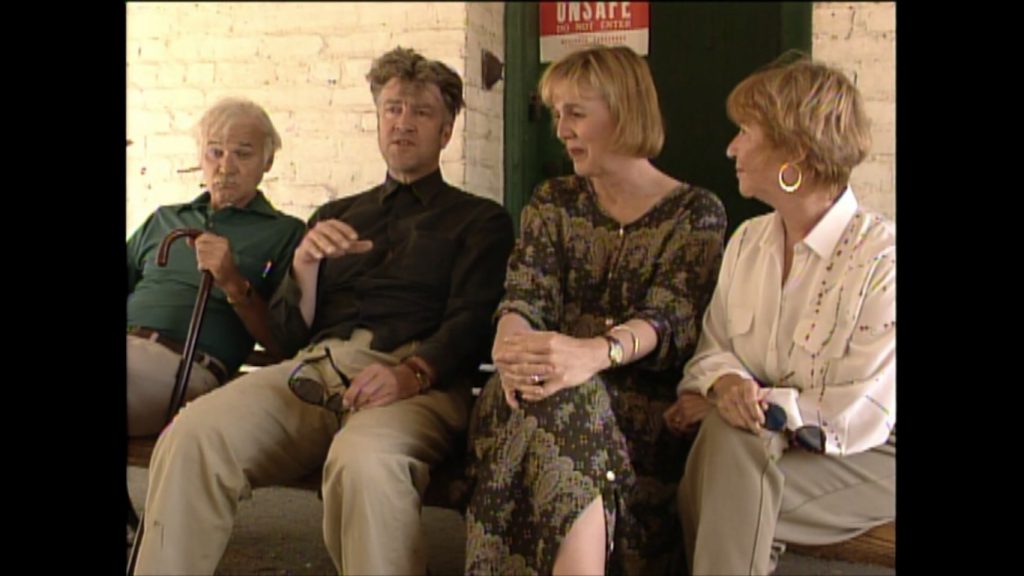

Production got underway in 1971. Alan Splet was back onboard to collaborate on the sound design. The rest of the cast and crew were all friends or friends of friends. The only part left to be cast was the lead and the first actor to audition turned out to be the perfect fit: Jack Nance.

Nance brought along his then wife, Catherine Coulson, who turned out to be super supportive. Not only did she do the hair and make up (yes, including that hair), she became the production assistant, sorted the catering, operated boom and learned on the job to be camera operator before stepping-up as assistant director! She also took a job as a waitress to top-up the budget. She would repeatedly work with Lynch over the next five decades and may be better known as ‘The Log Lady’ of Twin Peaks.

Lynch was working as a delivery driver for local newspapers and cutting corners where he could. He quit smoking and drinking and saved on rent by living on site, literally inhabiting the world of Eraserhead as he built the sets, usually with the assistance of Jack Nance.

Apart from the establishing shots of its barren industrial environment, all of Eraserhead’s world is entirely constructed. This gave Lynch total control over every aspect of the mise-en-scène. Just like his preceding short films, he incorporates his sculptural art, harking back to Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s Futurist film Thais (1914), which was one of the first genuine ‘art movies’ to intentionally incorporate sculptural sets.

Approaching the sets as an extension of sculpture ends up with a feel not unlike the German Expressionist films of the silent era. The minimal dialogue and long pauses between lines, filled with lots of emotive facial expressions, only adds to this effect. Henry looks like he may have walked straight out such a film and, throughout, the face of Jack Nance is almost the definition of expressionism!

The slowness of the pre-production meant that Lynch could treat the construction in much the same way as an artist approaches an installation. His ideas could ferment further as he and his team assembled the necessary equipment. The cameras were borrowed from the AFI and the stock scavenged from the bins of the Warner Bros. Studios. They bought up some extra props and equipment from an old studio that was closing down, and some antiquated but effective lighting gear was donated. And yet, they run out of money.

Famously, there is one edit in the film where Nance opens the door to his apartment, but the shot when he steps through it was shot a year later after one of the several hiatuses. Apparently, the project was only completed with the help of Lynch’s old friend from his art school days, Jack Fisk and his wife Sissy Spacek. The halting production finally sprawled across six years.

It was eventually premiered, with little fanfare, at the 1977 Los Angeles International Filmex Festival. Like a nervous father, Lynch paced back and forth outside the Theatre throughout the screening. The audience didn’t react how he’d hoped, and the press reviews ranged from dismissive to damning.

Believing the version he’d shown was too long, he immediately recut it and jettisoned whole scenes, reducing its duration by 20-minutes to the 89-minute version we know today. It would’ve been interesting to have those deleted scenes as extras on a special edition Blu-ray one day but, unfortunately, he’d cut the final composite print and discarded the footage.

…and that was nearly that for Eraserhead, and probably the career of David Lynch.

Fortunately, it had captured the imagination of alternative film distributor Ben Barenholtz, who had an innovative idea. He managed to interest cinemas in showing arthouse, exploitation and alternative films in an additional midnight slot and selected Eraserhead, along with John Water’s Pink Flamingos (1971), to show at the Cinema Village Theatre in New York.

The first few nights were sparsely attended but well received by a handful of punters. The film rapidly built a cult following and soon it was packing the auditorium. The cinema kept it in its midnight slot for a whole year, before the film moved on to another New York cinema, screening at midnight for nearly two years straight. Barenholtz had invented ‘The Midnight Movie’ and Eraserhead became a staple, earning his distribution company $7M over the first few years and twice that through overseas sales.

Eraserhead can be considered seminal in every sense. It certainly reminds me of many moments from films made since by David Lynch, and its influence is tangible in the work of so many others—‘Lynchian’ is now a term used when discussing cinema. Only a handful of directors achieve the accolade of having ‘ian’ or ‘esque’ suffixed to their names: Hitchcockian, Wellesian, Felliniesque… Tarkovskyesque.

It’s not only Henry’s hair that’s accrued iconic status over the 43 years since it was first screened to small, baffled audiences. The man-made menstruating chickens, the unnamed mutant baby, and not least the singing lady in the radiator (Laurel Near), have all escaped the confines of their original context to become cultural memes.

In 2010, the Online Film Critics Society ranked Eraserhead as the second best directorial debut of all time, after Orson Welle’s Citizen Kane (1941). In 2011, The Guardian invited a panel of international critics to rate the top 40 directors in the world, using a point system. Lynch topped the list, beating Martin Scorsese by one point. This is how Lynch’s score panned out: Substance 17, Look 18, Craft 18, Originality 19, Intelligence 17, Total 89 out of a possible max of 100. Personally, I think they were being a bit stingy!

USA | 1977 | 85 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

writer & director: David Lynch.

starring: Jack Nance, Charlotte Stewart, Allen Joseph, Jeanne Bates, Judith Roberts.