SILENT RUNNING (1972)

One man struggles to preserve Earth's last remaining forests, shipped off to deep space.

One man struggles to preserve Earth's last remaining forests, shipped off to deep space.

The two Joan Baez songs that erupt into the quiet spaceship world of Silent Running are, to put it politely, very characteristic of their time. The same might be said of the film itself, which at least on the surface exhibits that characteristic late-1960s/early-1970s fusion of cynicism and naivety. Indeed, it was one of several movies that Universal Pictures funded precisely in order to capitalise on the counter-cultural youth market whose potential had been made obvious by the success of Easy Rider (1969).

But while Silent Running doesn’t escape the charge of naivety entirely, and it’s never wholly clear whether some of the ideas it puts forward are deliberately contradictory or simply confused, it remains of great interest—both as a product of its era, and as one of only two directorial outings from Douglas Trumbull, the VFX genius famous for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and Blade Runner (1982).

Indeed, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 was directly, if inadvertently, responsible for this film. The young Trumbull, only in his mid-twenties when 2001 was released and not yet 30 when Silent Running came out, was reportedly frustrated that despite the role played by the former film’s effects, Kubrick got all the kudos. And he was also disappointed that some of the action in 2001 had been relocated from the vicinity of Saturn to that of Jupiter, after creating Saturn’s rings had proved to be an insuperable problem.

In Silent Running, though, not only could Trumbull claim authorship of the whole film for himself, but he could also ensure that the rings figure prominently. Perhaps they’re not totally convincing seen at a distance, but when the giant spacecraft of Freeman Lowell (Bruce Dern) has to pass through them, the intense, buffeting experience is vividly rendered.

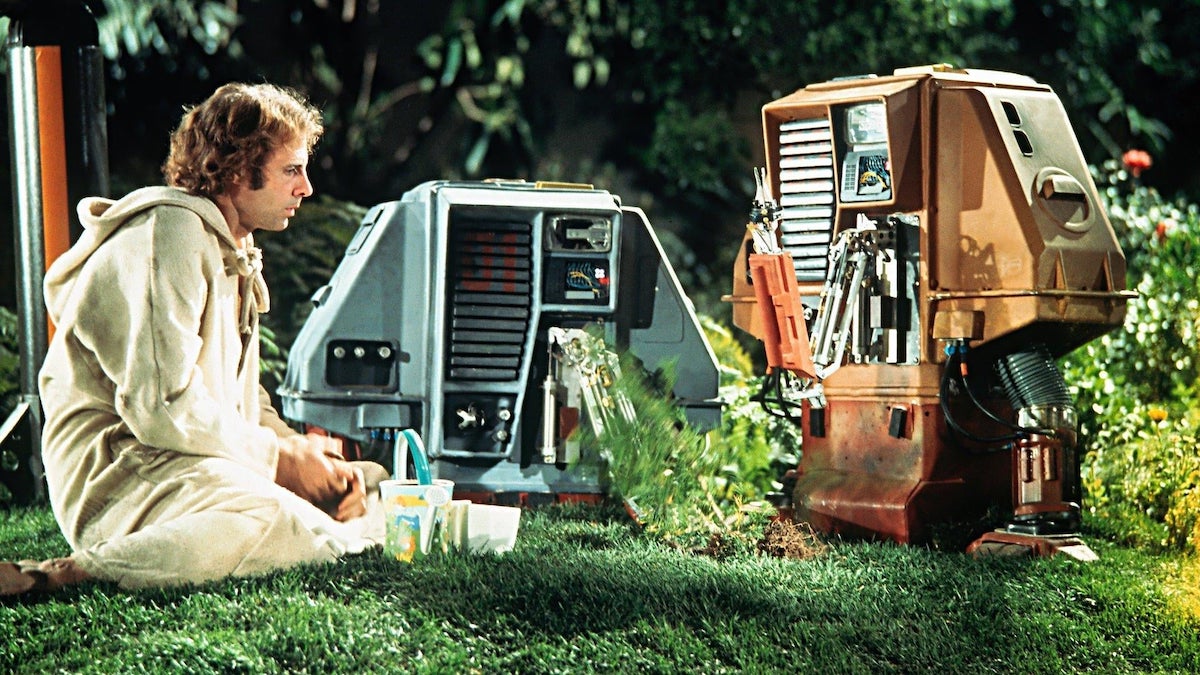

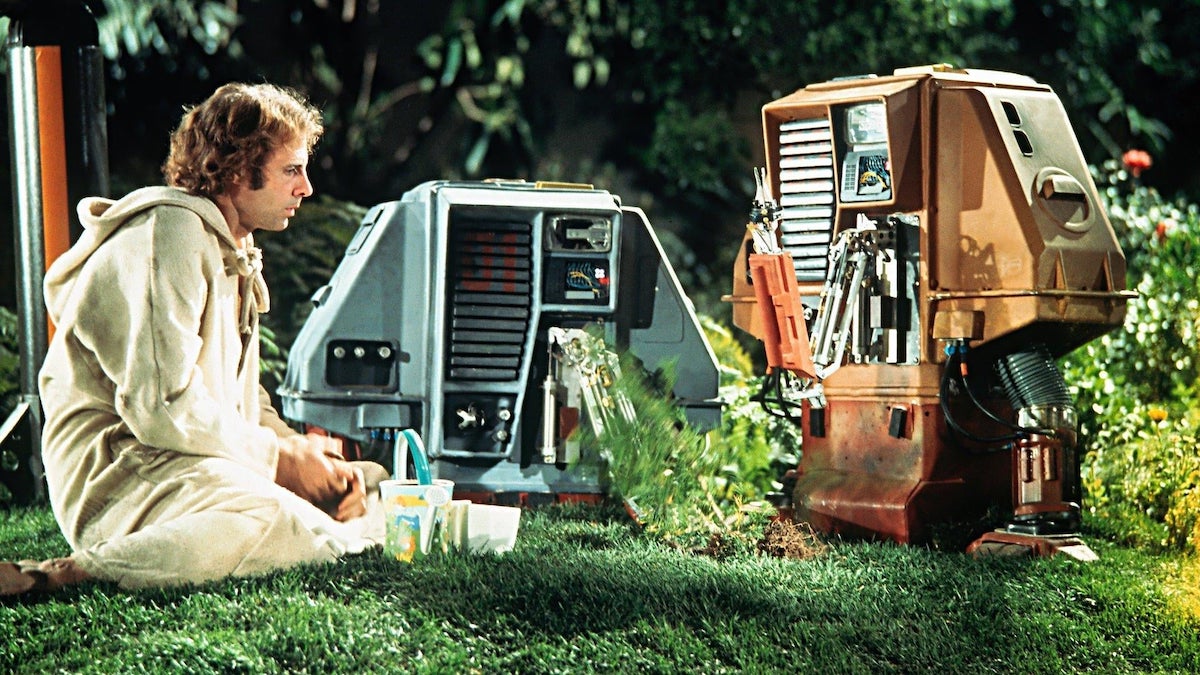

Despite this, however, Silent Running isn’t a VFX-led film at all, and it opens—very intentionally—with a scene that doesn’t even suggest science-fiction. We see flowers, foliage, some small animals… a man bathes in what appears to be a pond… rabbits gambol… but then the camera pulls back to reveal a structure, and soon it’s apparent this is a vast geodesic dome.

Freeman (besides its obvious symbolism, does his name echo 2001’s Bowman?) and three other crew members (Cliff Potts, Ron Rifkin, Jesse Vint) are, we now learn, piloting one of several enormous craft on which the flora and fauna of their home planet are stored. The year is 2008 (the future for Silent Running, of course), and one day these plants and animals will be returned to repopulate a world shorn of them by unspecified (but surely profit-driven) environmental disaster.

Their craft, the Valley Forge, is almost literally a “spaceship Earth” (to use the phrase created by Buckminster Fuller, champion of geodesic domes)—and in this, no doubt, Universal hoped to tap in to the ecological awareness typified by the celebration of the first Earth Day in 1970 and by reactions to the Apollo programme’s pictures of a small, vulnerable Earth from space.

The mission of Valley Forge and its fellow craft feels almost sacred, and Freeman seems appropriately almost Biblical in his long white cloak.

But there’s scepticism in Trumbull’s film too; snakes in this Eden. While Freeman tends his plants, his colleagues tear through the spacecraft (in fact a decommissioned aircraft carrier) on motorised buggies. They prefer the artificial food prepared by the craft’s machinery to the fresh meals that Freeman prepares with the vegetables he grows.

Most importantly, before long comes the order to nuclear-destruct the floating gardens and “return our ships to commercial service”—this one is operated by American Airlines. And thus Silent Running sets up a conflict between Freeman on the one side, and his colleagues and their employers and their orders and (presumably) the whole establishment of Earth on the other, all of which boils down to one thing: should he destroy the last remnants of the natural world in order to return some expensive property to its legal owner?

Superficially, the answer looks as obvious now as it would have in 1972, but Silent Running’s creators are sophisticated enough to inject some difficulties into the situation and its development.

First, the world from which these pockets of nature have been salvaged may be environmentally despoiled, but it is not quite a hellhole of the kind portrayed in films like No Blade of Grass (1970) or Soylent Green (1973). Instead, it owes more to the Brave New World vision of dull, sterile perfection. As Freeman’s fellow crew members observe, the temperature on Earth is a balmy 75 degrees (presumably Fahrenheit!) everywhere, while disease, poverty and unemployment have been eliminated.

However, counters Freeman, so have beauty and imagination. And as Silent Running progresses, it becomes evident that simply making Earth a better place for humans again is not the movie’s only desideratum.

Freeman himself may seem to be saintly at first, but once he’s alone in part of the ship, he starts racing a buggy too, remembering his colleagues wistfully, playing cards with robots as he used to play cards with them—is he, underneath, much more like the other guys than we (or he) had realised?

These accumulating hints that the problem may lie in humanity generally rather than in specific attitudes of specific humans are among the more thoughtful touches in a film that sometimes seems to beat you over the head with its ideas. They’re confirmed when Freeman starts messing up his own environment (never mind the notion of him being unaware of photosynthesis is far-fetched; the shots of dying plants and accumulated human detritus are effective).

And they are emphasised at the end of the film, in a single brief scene following a powerful zoom-out climax, which appears to imply that the real win is the natural world surviving for its own sake.

It’s never clear whether Silent Running is supporting the idea that the Earth would be better off without humans, or satirising it, or both. This may partly derive from a change of focus during the film’s production—it was originally intended to build up to an alien encounter, which doesn’t occur in the released version—and the performances aren’t much help in making sense of it all, either.

The key issue here is that Dern’s Freeman isn’t a particularly likeable character: he seems arrogant and close-minded, and Dern’s over-emoting exacerbates this (though he does do nervousness well, and scenes where he’s dissembling to his superiors over the radio are more convincing). The other three members of the crew, meanwhile, are simply wooden. So there’s nothing in the acting to suggest where, if anywhere, we should empathise.

Or not in the human acting, at least, because many of the best moments (including the burial of a human) belong to the little robots (or “drones”), which Freeman names Huey, Dewey, and Louie and which become real characters in the latter parts of the film.

Clear antecedents of R2-D2 and WALL-E, they aren’t too humanoid in their appearance—and while they’re occasionally too anthropomorphic in behaviour to take seriously, for much of Silent Running they provide the third point in a triangle of human life, non-human life, and technological “life”. Just once, a great cut to a drone’s-eye-view suggests that there is a whole other perspective on all the film’s events.

It may be the biggest irony of this film concerned with the preservation of life, then, that the inanimate components—the production design (utilitarian spaces jammed with CRT monitors) and the robots—are so much more believable than the living people.

Critics were broadly positive at the time, even if Dern’s performance divided them, as did the question of whether Silent Running is profound or simply muddled. Dern rapidly solidified his claims to stardom, if never quite its highest level; Trumbull, though, directed only one other movie, the now little-known Brainstorm (1983).

Two of the screenwriters went on to greater things: Michael Cimino (here “Mike”) briefly so with The Deer Hunter (1978), Steven Bochco for a longer period with a career that included Hill Street Blues. The composer of the original score, Peter Schickele, left the movies and created the successful, long-running classical music parody character P.D.Q Bach.

Their work on Silent Running created a film that’s far from perfect. Much of it is frustratingly indistinct (ranging from the meaning of the title to the moral agenda, if any), and not all the pieces fit well together. We can guess at what it all means, certainly, but there’s a nagging suspicion that some of the perceived meaning might be inadvertent.

But it’s a haunting film, perhaps in part because it touches on so many questions, even if it leaves them unanswered. One exchange, over the radio between Freeman and his superior elsewhere, typifies this; “You’re a hell of an American,” says Freeman’s boss, to which the now-renegade botanist replies with an irony unsuspected by the other man “Thank you, sir, I think I am.”

What it meant to be a good citizen of the United States was much in contention in 1972; and what it meant to be a good citizen of Earth was starting to be discussed too. Silent Running, for all its flaws, at least tries to take an honest look at that, and faces up to some uncomfortable implications.

USA | 1972 | 89 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Douglas Trumbull.

writers: Deric Washburn, Michael Cimino & Steven Bochco.

starring: Bruce Dern, Cliff Potts, Ron Rifkin & Jesse Vint.