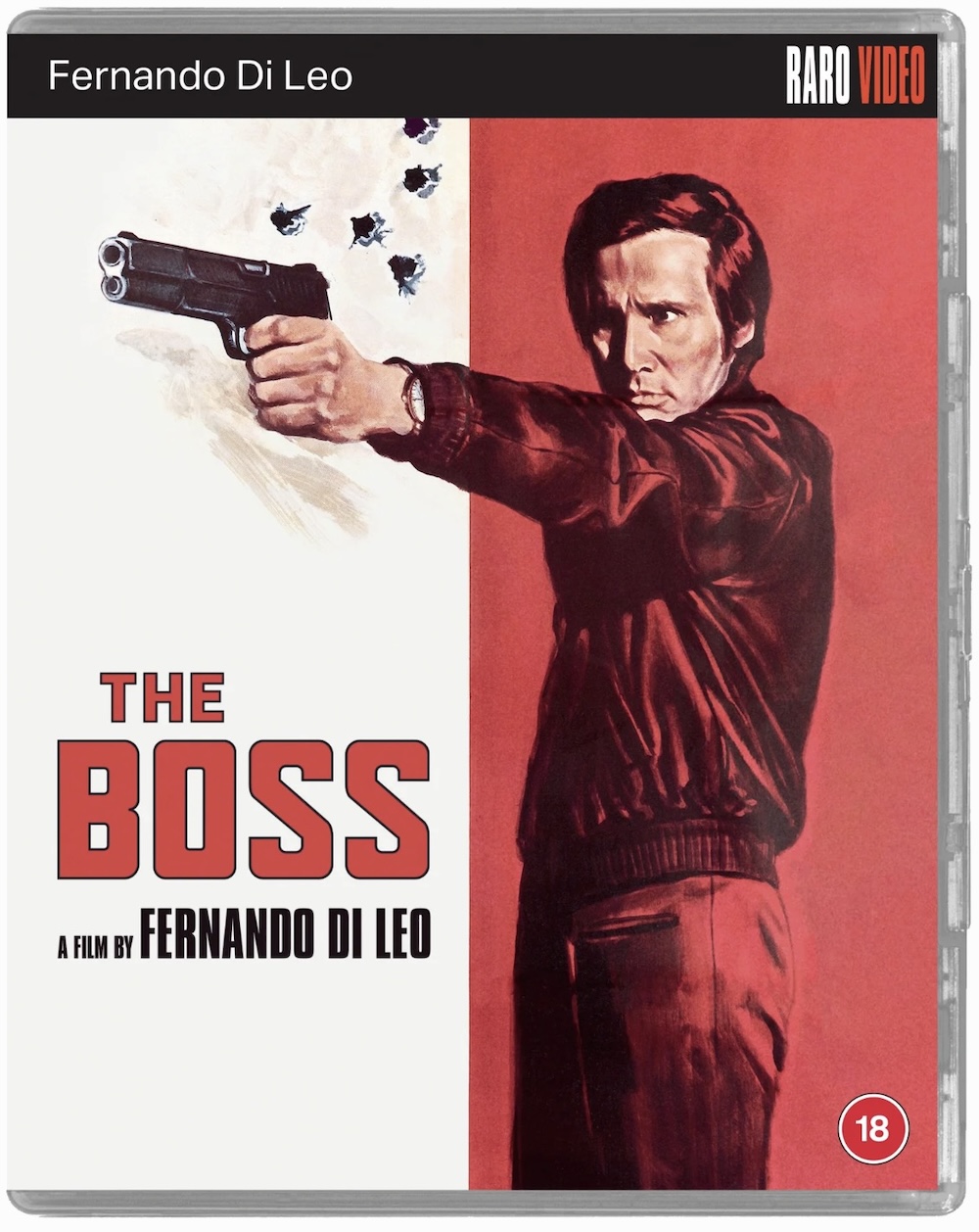

THE BOSS (1973)

A hitman finds himself embroiled in the middle of a Mafia war between the Sicilians and the Calabrians.

A hitman finds himself embroiled in the middle of a Mafia war between the Sicilians and the Calabrians.

In less than two years, Radiance Films has carved a niche for itself by releasing high-quality restorations of important cult films and arthouse classics that might otherwise have been lost to a new generation. I’m delighted that they’ve made it their mission to cater to the rekindled interest in 1970s Italian genre cinema. A few years ago, the terms giallo and poliziotteschi were obscure, even amongst cinephiles, and films of those subgenres were like endangered species that had all but vanished from cinematic histories. So, hot on the heels of last month’s release of Duccio Tessari’s Tony Arzenta (1973), it’s wonderful to get the chance to see Fernando Di Leo’s The Boss / Il Boss—a crime thriller featuring another coldly efficient Mafia enforcer—with a 4K restoration of the original negative on Blu-ray for the first time in the UK.

The opening shots are beautifully composed by the assured cinematographer, Franco Villa, who exploits the stark noir shadows of a city at night as Nick Lanzetta (Henry Silva) crosses the road carrying a large, ominous case. The jazzy score by prolific composer Luis Bacalov sets the mood with its deep bass line and jarring percussion as he enters a large, anonymous building. The importance of music in the identity of 1970s Italian genre cinema cannot be overstated, and many a film has been rescued by an inspired soundtrack. Inside, a group of mafiosi are exchanging macho, innuendo-laden banter as they settle down for a private screening of a newly imported pornographic film, of which we only get to hear the sleazy jazz soundtrack.

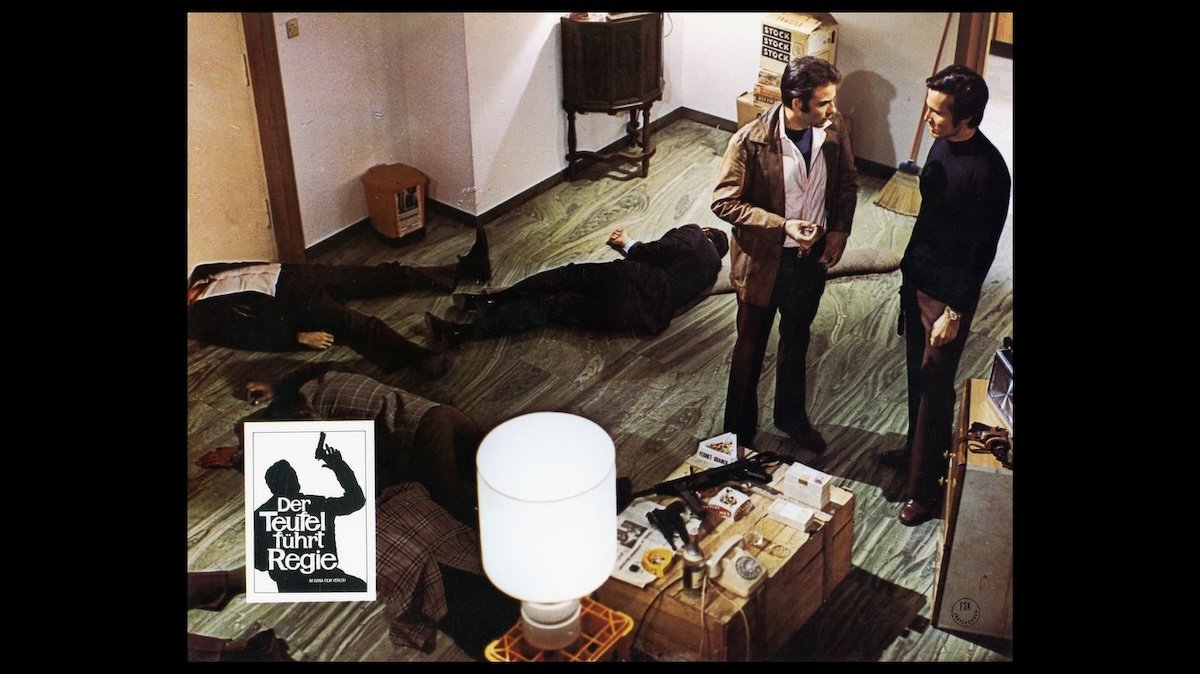

Unbeknownst to them, the projectionist has already been overpowered. Lanzetta calmly fits a grenade launcher attachment to his rifle before firing it several times into the auditorium. The scene cuts to burning corpses intercut with a montage of Lanzetta phoning Don D’Aniello (Claudio Nicastro) to coolly inform him that the ‘transactions’ have been concluded. The brutal violence of the opening scenes is only slightly mitigated by the fact that it’s clearly mannequins being blown to bits.

Here, we’re also introduced to two other key characters: Rina (Antonia Santilli), Don D’Aniello’s daughter, who answers the phone initially, and Sicilian Mafia boss Don Corrasco (Richard Conte), whom D’Aniello calls immediately to pass on the news that the ‘payment’ has been dealt with. Telephones will be a recurring motif of dehumanisation throughout the film. Orders are given, and information is received remotely, often in coded language that uses financial jargon to discuss matters of life and death.

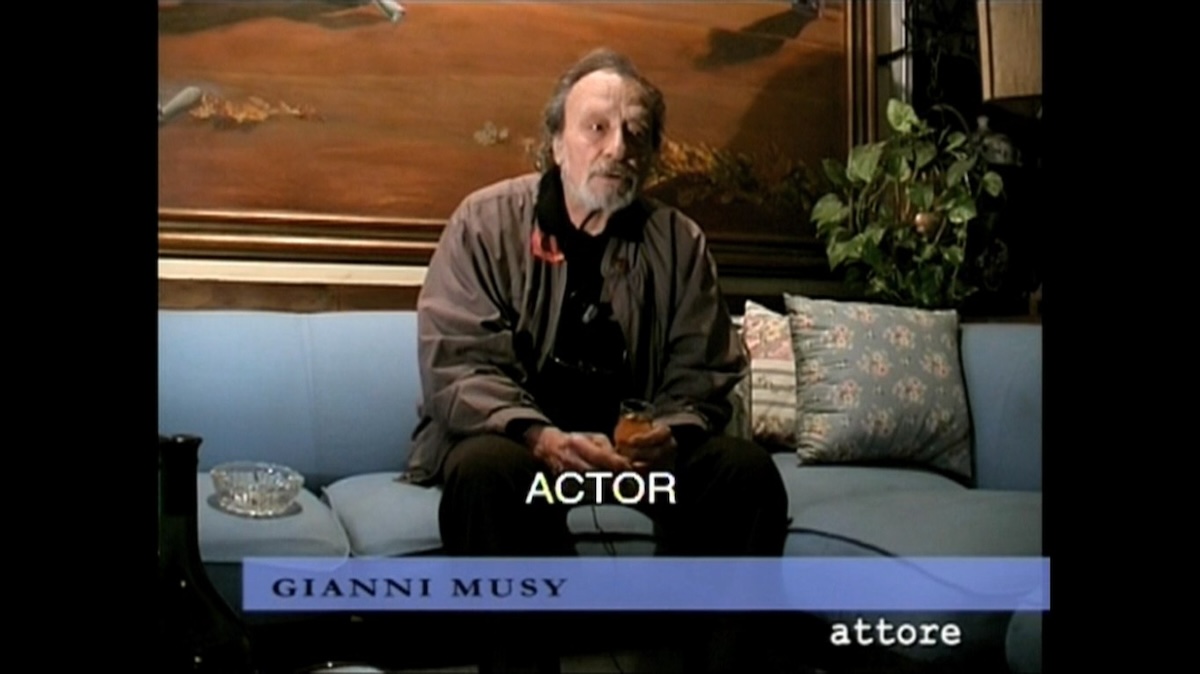

Within the first few minutes, we’ve witnessed the assassination of Don Antonino Attardi (Andrea Aureli) along with most of his ‘family’—except for his brother Carlo (Gianni Musy) who had left the screening and will return later to complicate matters. This is the catalyst for all that follows, as the eradication of one Mafia boss destabilises the hierarchy, triggering bitter rivalry in the reshuffling of power. This is what worries corrupt Police Commissioner Torri (Gianni Garko), and what the ruthless Cocchi (Pier Paolo Capponi) sees as his opportunity to move up an echelon.

The film boasts a strong leading cast. Gianni Garko plays Torri as a right-wing bigot who uses bluster and bravado to hide his weaknesses and fears. He was more used to playing less ambiguous leads in Euro-westerns such as Romolo Guerrieri’s $10,000 Blood Money (1967) and Giovanni Fago’s Vengeance Is Mine (1967) and I remember him from Lucio Fulci’s excellent giallo, The Psychic (1977).

Richard Conte was on familiar territory, having just appeared in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972). He doesn’t seem to find this part all that challenging and is, perhaps, the least convincing. He mainly acts by jabbing his fingers at people, desks, and armchairs. But he’s playing a man who is playing to the expectations of others and has already lost himself along the way. So both actor and character seem to be simply ‘going through the motions’. By the time he reprises a very similar role in Tony Arzenta, he’s honed it further and introduced a lot more depth.

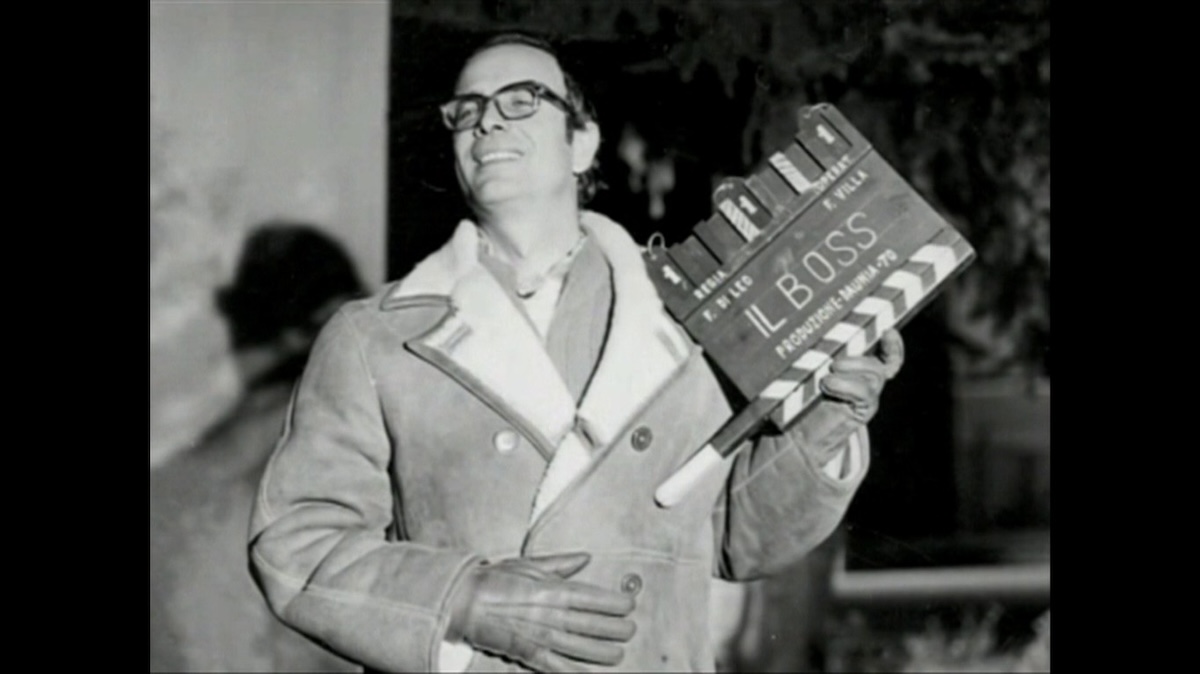

Like The Godfather, The Boss (also known as Murder Inferno) was also based on an American novel published in 1971. In this case, it was Il Mafiosa by Peter McCurtin and Fernando Di Leo’s adaptation is fairly faithful to the central story but with the action transferred from New York to Palermo. As well as a notable director, Di Leo was a respected and prolific screenwriter having written several classics that broke open the international market for Euro-westerns. These included Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and Duccio Tessari’s excellent Ringo duology (1965), among many others.

It may not be immediately apparent that all the key performances here are excellent. Some viewers might perceive them as brash and unsubtle, and, indeed, some of the characters are brash, as well as uncouth and monstrous. Nearly all the characters are conniving and deceitful, saying one thing while manoeuvring and manipulating the situation for personal gain. They lie like politicians, and there’s a deliberate blurring of the lines between the mafia, police, and government. This certainly reflects the real socio-political situation during the so-called ‘years of lead’ when activists outdid criminal gangs in terms of atrocities, the police opened fire on protesters, and politicians weren’t above having their rivals assassinated.

Pier Paolo Capponi had recently starred in several memorable gialli, including Luciano Ercoli’s The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion (1970), Dario Argento’s Cat o’Nine Tails (1971), and Umberto Lenzi’s Seven Blood-Stained Orchids (1972). He was a good friend of Fernando Di Leo, and their professional relationship had become a collaborative one. They discussed the role of Cocchi, a surviving Attardi family enforcer, at length.

Instead of the usual, ‘ready-to-wear’ villain, the character became more complex and multifaceted. His simmering violence might stem from the sense of powerlessness he felt as a child growing up in poverty. His resentment of authority is fuelled by the frustration of seeing the privileged few exploit the masses, the rich stealing from the poor. But he proclaims that pain and hunger make one stronger, and the desperate, who have nothing to lose, are prepared to do anything. His humanity has been consumed by rage, and regardless of what aspects of his past caused such deep psychological scars, he is now a monster.

Cocchi knows that Don D’Aniello ordered the hit on the Attardi family and begins to plot a suitable retribution. However, this isn’t out of a sense of righteous vengeance. D’Aniello clearly intends to take over the Attardi markets of importing drugs and pornography, but Cocchi sees himself in that role. If he can eliminate D’Aniello, he could also take on that family’s business interests at the same time. So, he recruits a new gang of street thugs, drug dealers and student activists to kidnap Rina D’Aniello. He then presents his ultimatum: Don D’Aniello must give up his own life in exchange for his daughter’s.

Don Corrasco, the boss of the Sicilian Mafia, won’t allow any concession to such intimidation, even at the cost of Rina’s life. However, Lanzetta intervenes with a plan that might save her and put a stop to Cocchi’s power grab once and for all. Instead of a life for a life, he suggests offering Cocchi a phenomenal amount of lira to buy Rina back, knowing that all criminals will succumb to the power of cash. But this is just a ruse to find out where Rina might be held captive and attempt a rescue by stealth or deadly force. Corrasco agrees to the plan but also gives Lanzetta covert orders to kill Don D’Aniello should he try to use the money to negotiate for Rina’s release. It’s a positively Shakespearean premise.

Modern audiences might still find some of the content shocking, particularly the nonchalant cruelty and dialogue riddled with misogynistic and racist remarks. But really, it should come as no surprise that 1970s mafia thugs and drug dealers weren’t at all woke.

The most problematic scenes involve the abuse of Rina and her responses. Presented to the camera stripped down to her underwear, she is certainly serving the male gaze as she suffers verbal assaults from Cocchi who uses the threat of rape to intimidate her. She surprises her captor by requesting some whisky so she can relax and enjoy his men. It seems she’s no stranger to drink, drugs, casual sex, and threesomes. Turns out she’s been using such behaviour to rebel against her father, his insincerity, and the double standards of a man who pretends to be a devout Catholic while profiteering from crime and ordering executions.

Despite her background in sexploitation movies and previously appearing nude in glamour magazines, Antonia Santilli found the role challenging. This was before the days of closed sets and intimacy coordinators, but others have claimed she was treated kindly by fellow cast and crew. It seems Capponi tried his best to be extra caring of her well-being after he had to berate and threaten her so cruelly. Neither he nor she were comfortable with their characters, but it would’ve been concerning if they were. Her performance is complex, unconventional, and convincing though her relationship with Lanzetta really needed more time to breathe but is instead compressed into a few sensationalised scenes. Because of this, some of her later dialogue feels non-sequitur.

The transgressive psycho-sexual subtexts could be a subject of lengthy debate in the context of post-war sexual liberation and the challenges it presented to the power of Catholic guilt and traditional masculinity in Italian society. Although Rina has been raised in an ostensibly privileged family setting, she too is damaged, though I can’t think of a character here who isn’t.

There are no good guys, just a spectrum of villainy, and we find ourselves rooting for Lanzetta, the protagonist, because he’s a cold-blooded, calculating killer. It seems he’s been raised for this role, adopted from an orphanage and all records of his existence erased. All his life, he’s been indoctrinated by mafia rules of honour, as if they’re the dogma of a secret cult. He’s the only character who doesn’t succumb to the lure of money but adheres strictly to this twisted code of ethics. Because of this, he becomes a threat when those in power resort to dishonourably double-crossing each other.

Subtext is all actors have to work with between their lines, and here that’s pretty much all they have. For the most part, the lean dialogue is expositional, but it’s what the cast does in the gaps that reveals their thoughts and motivations. Except perhaps for Lanzetta, whose expression barely changes throughout, even when he slaps vulnerable women around—possibly as a proxy for his own self-loathing. The only time he appears relaxed and allows a hint of human emotion to show through is when he looks upon Rina while she sleeps, and there’s no one else around to see his façade drop. It’s a clinically precise performance from Henry Silva that manages to convey the character’s internal world with the minimum of perfectly timed cues.

After a slew of small-screen appearances, primarily in mystery thrillers, Henry Silva’s first major supporting role came in John Sturges’s western The Law and Jake Wade (1958). His brooding presence and distinctive looks landed him a string of similar roles. He first starred as a mafia hitman in Raoul Lévy’s French noir film, Je vous salue, mafia! / Hail, Mafia! (1965). He then spent the late-1960s and early-1970s between the US, where he took on many small-screen roles, and the thriving Italian film industry, where he starred in several genre films. These include Emilio Miraglia’s Quella carogna dell’ispettore Sterling / Frame Up (1968), Maurizio Lucidi’s WWII espionage thriller Probabilità zero / Zero Chance (1969), which was written by Dario Argento, and La mala ordina / The Italian Connection (1972), written and directed by Fernando Di Leo.

The Italian Connection is the middle film of Di Leo’s violent Eurocrime triptych, which began with Calibre 9 (1972) and is completed with The Boss. These three films are cited as definitive early examples of the poliziotteschi genre, but they are a little atypical in that brutal cops are not a major element. Instead, the focus is on the unsavoury villains—drug dealers, pornographers, armed robbers, hitmen, gangsters. Although these three films work as an anthology, offering different vignettes into the world of swift violence that is grounded in the reality of the times, they can also be enjoyed as standalone stories.

Alongside the giallo, the stylistic innovations of poliziotteschi often involved cleverly staged set-pieces with audacious camerawork, and sophisticated subtexts sometimes hidden behind their brutality. This marked them apart from much of Italy’s pulp cinema and, in their heyday, these films were provocatively transgressive, brimming with political incorrectness that caused trouble with the censors and often resulted in bans in some territories.

Di Leo had already been cleared of obscenity charges concerning the content of his sexploitation film, A Woman on Fire (1969). However, Christian Democrat politician, Giovanni Gioia, pressed charges against him for referencing his name in The Boss, implying links to the Palermo mafia. Di Leo stood his ground, insisting he would only remove the reference if it were untrue. Consequently, Gioia withdrew the charges and faced scrutiny from the Parliamentary Anti-Mafia Commission. Di Leo, ever the opportunist, was grateful for the free publicity the case generated for the film, further highlighting how closely the narrative mirrored reality. Upon release, The Boss became a major domestic success, with reports of fights erupting between cinemagoers desperate for a seat in the sold-out screenings.

ITALY | 1973 | 109 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN • ENGLISH

director: Fernando Di Leo.

writer: Fernando Di Leo (based on Peter McCurtin‘s novel).

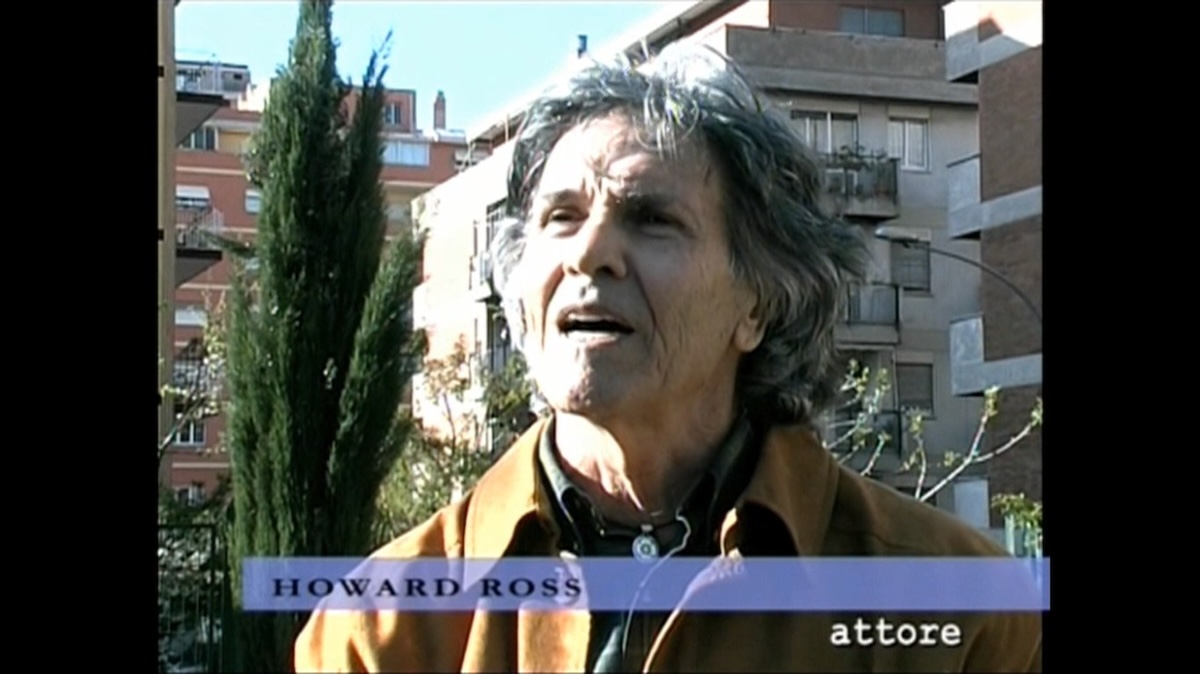

starring: Henry Silva, Richard Conte, Gianni Garko, Antonia Santilli, Pier Paolo Capponi, Claudio Nicastro, Howard Ross & Gianni Musy.