BLACK MASK (1996)

A survivor of a supersoldier project must fight his former comrades as a masked hero.

A survivor of a supersoldier project must fight his former comrades as a masked hero.

Black Mask / 黑俠 is a fantastic example of a 1990s Hong Kong action film, and Eureka Entertainment has put together a package that’s sure to delight completists. This is the UK and US Blu-ray debut of the definitive uncut Hong Kong version and the original US version, both restored from 2K scans. There’s also a second bonus disc featuring the alternative Taiwanese cut of the film, plus a specially reconstructed version that incorporates all the unique elements from the different releases. For anyone who enjoys fast-paced martial arts action with a science fiction twist and doesn’t mind a bit of body-horror thrown in, there’s plenty to savour here.

Manhua is the collective term for comic-books produced in China that share many similarities to Japan’s manga, and Li Chi-Tak is probably their most influential creator. He’s responsible for kick-starting the serious Chinese superhero genre with his 1992 series Black Mask and is cited as the ‘Father of Indie Comics in China’. Apparently, the title, 黑俠—literally ‘black man’, meaning a man in black—can be translated as ‘Dark Knight’ and it’s likely that Frank Miller’s Batman reboot with his distinctive, often high contrast noir-ish artwork was an important influence on Li Chi-Tak’s stark black and white aesthetic. Like Batman, the Black Mask character of the comics is an orphan who becomes a determined vigilante.

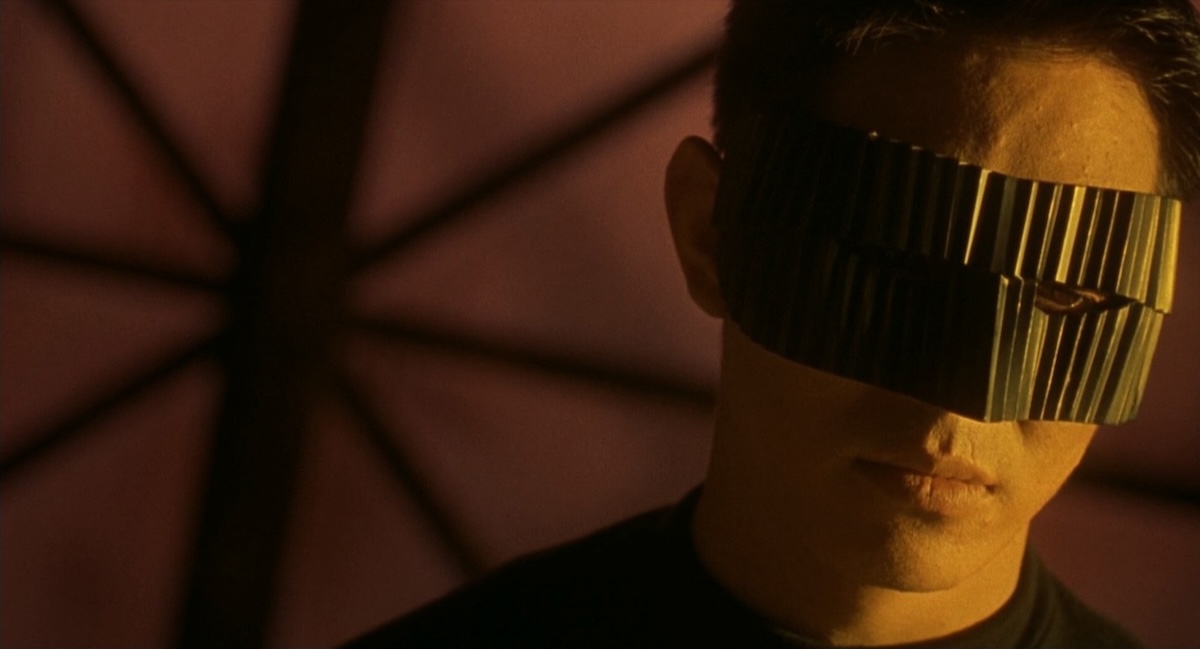

In the film, director Daniel Lee attempts to evoke this graphic novel style through extensive use of oblique lighting. This bleaches out parts of the screen while plunging others into deep shadow. While occasionally effective, it can also veer into territory reminiscent of a cheesy pop video from the era. This effect is likely amplified by the clarity of the excellent restoration.

There are a few wide shots that look like a splash page or double-spread, but for the most part, his restless camera draws on the dynamic design of Li Chi-Tak’s panels. It’s constantly tilting, tracking, and presenting a rapid array of interesting angles. However, this is a reboot and establishes a very different origin story for the seminal superhero.

In the opening montage, we learn that in an unnamed ‘country up north’—perhaps mainland China or Russia—a top-secret military experiment created a group of super-soldiers, known as the 701 Squad, by apparently ‘removing their nerves’. What? Yes, the science is incredibly vague and leaves many gaps for the viewer to fill in. But whatever was done to this select group rendered them near invincible. The authority that created them, fearing they would become uncontrollable, now saw them as a threat. So, the programme was aborted and the 701s were set against each other with orders to eliminate their former comrades.

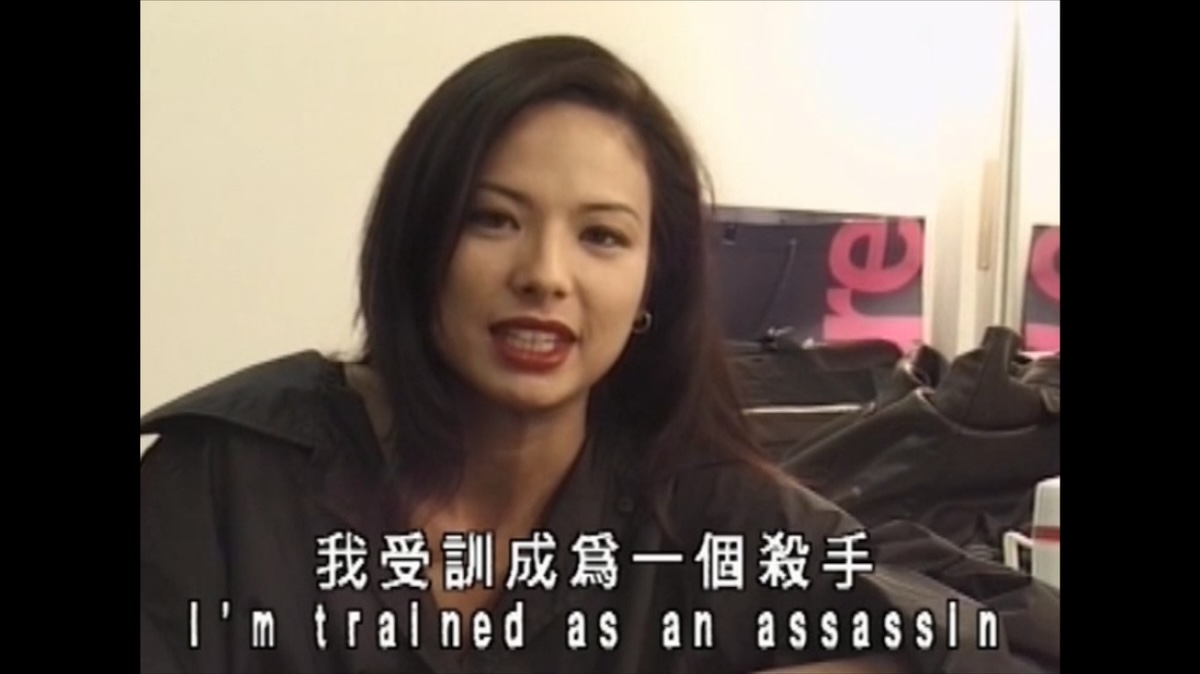

We meet two of the 701s as Yeuk Laan (Françoise Yip) breaks the news to her mission partner and combat instructor (Jet Li) that the 701 experiment has been terminated. Forewarned, he walks into a trap to confront a heavily-armed platoon and acrobatically fights his way out against machine guns, grenades, tanks, and rocket launchers. By the end of this spectacular opening scene, he’s presumed dead in a massive explosion. But of course, with Jet Li being the star, we know that’s not quite the case…

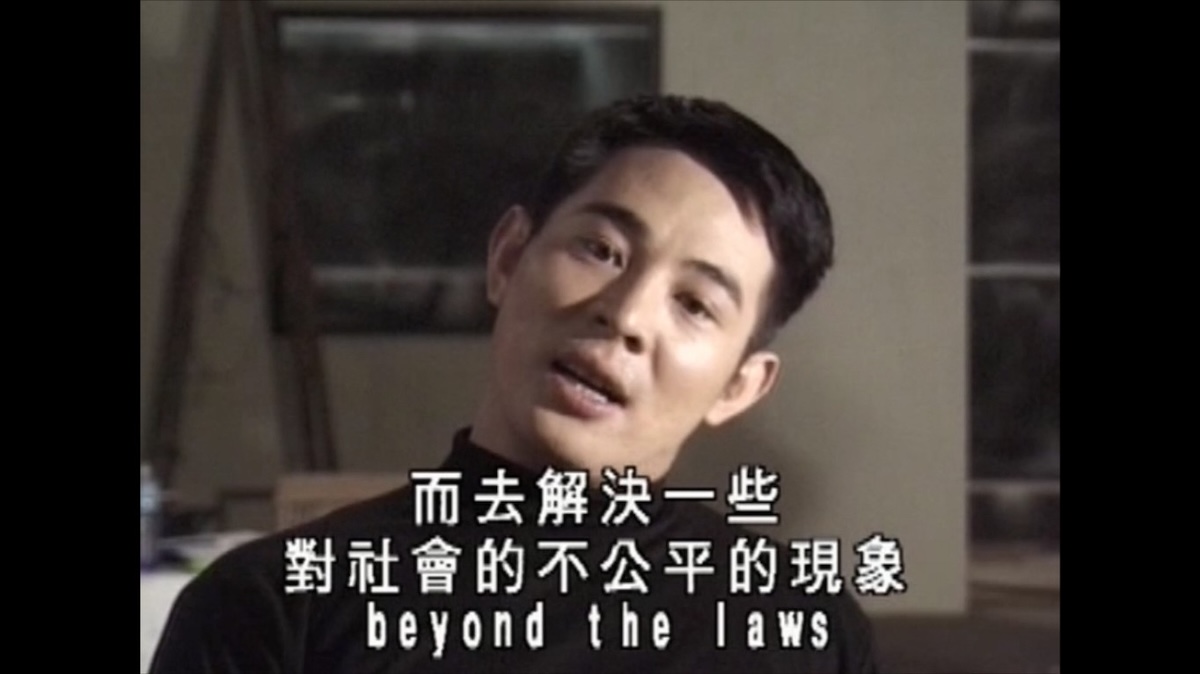

After achieving superstardom with his recurring roles as two legendary heroes—Wong Fei-Hung in Tsui Hark’s Once Upon a Time in China trilogy (1991-92) and Fong Sai-Yuk in Corey Yuen’s Legend duology (1993)—Jet Li is undeniably the main draw here. He was, at the time, looking for roles that would showcase the breadth of his talents beyond wuxia and period kung fu films, hoping to attract the attention of foreign casting directors. This ultra-violent science fiction superhero genre was relatively new to Hong Kong cinema, but it had proven popular in overseas markets since the emergence of cyberpunk in the 1980s, with films like RoboCop (1987) and Universal Soldier (1992)—two clear influences on Black Mask.

This period saw Hong Kong action cinema shedding the distinctive visual identity it had established in the 1970s and 1980s. Directors and stars faced a choice: impress the burgeoning Chinese market that was about to absorb them, or make a bid for Hollywood by appealing to Western audiences. As a result, many looked to overseas trends and attempted to emulate them.

The 1997 handover loomed, when Hong Kong would cease to be a British colony and be absorbed into mainland China. That process had been underway since mid-1985, when the Sino-British Joint Declaration came into effect. The agreement stipulated that after the transfer of governance, China would protect Hong Kong’s legislative system, people’s rights, and freedoms for the ensuing 50 years as a special administrative region. Some suspected that the terms were open to interpretation and might not even be honoured. China effectively ended that arrangement, 28 years early, when it introduced the Hong Kong National Security Laws in 2020.

After setting the scene, we rejoin the story some time later. Tsui Chik (Jet Li), a geeky librarian, leads a secret double life as Black Mask. His friend and regular chess opponent is none other than Inspector Shek ‘Rock’ Wai-Ho (Ching Wan Lau), a tough police inspector struggling to deal with rapidly escalating gang violence. Rival drug lords in Hong Kong seem to be eliminating each other. He’s also hot on the trail of a vigilante known as, you guessed it, Black Mask. The scenario echoes the familiar uneasy partnership between Bruce Wayne and Commissioner James Gordon from Batman.

In the aftermath of a bloody massacre involving an acid sprinkler system and cars being dropped from the dock cranes, Tai (Henry Fong) is the sole survivor of his gang. He was betrayed by his own henchman (Dion Lam) who implanted a bomb in Tai’s chest with some quick dockside surgery. In the hospital, the bomb disposal squad works under the guidance of a brave surgeon to defuse the device, which is rigged to explode if the patient’s heart rate falls below a certain level. Inspector Shek waits in the hope of interrogating Tai if he’s revived, but is called away after being tipped off that the bomb is a double bluff and will detonate if any attempt is made to remove it. The call is from Tsui Chik and proves to be correct, arousing Shek’s suspicions about his librarian buddy.

Tsu Chik had recognised the modus operandi and knew some survivors of the 701 Squad were plotting to eliminate all the drug dealers and their entire infrastructure. However, their motive wasn’t to clean up Hong Kong, but to create a power vacuum they could step into. Their Commander (Patrick Kong Lung), who’s now more of a cult leader, was orchestrating this masterplan ostensibly to fund research into a cure for their inhuman condition. But the idea of taking over the international crime network was becoming increasingly attractive—a way to rule the world ‘from the bottom up’. Realising that Black Mask was their only serious obstacle, he dispatched his disciple, Yeuk Laan, to bring him on side or execute him.

The plot offers maximum opportunity for mayhem, and anyone looking for excellent stunt work and impressive Hong Kong-style action won’t be disappointed. The fight scenes are fast, intricate, and precisely choreographed by Yuen Wo Ping, a master of the craft who had already worked repeatedly with Jet Li, most notably on the Once Upon a Time in China films and Fist of Legend (1994). Although he’s now better known for his later work on Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and the Wachowskis’ Matrix trilogy (1999–2003).

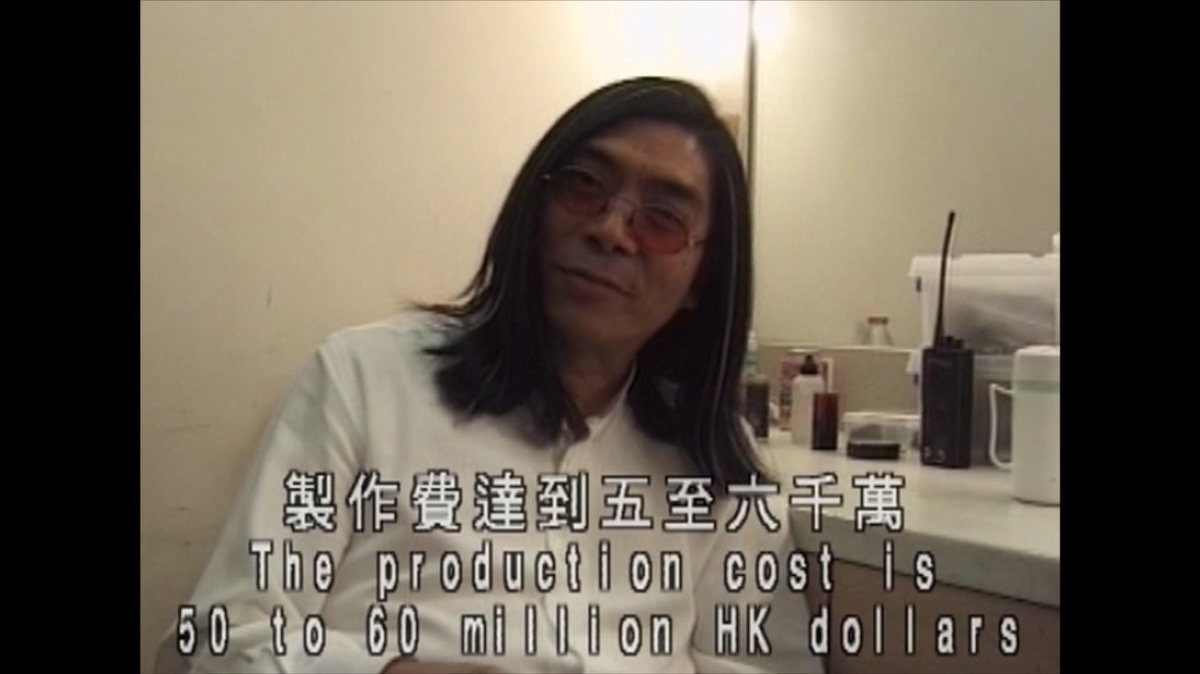

It’s a Hong Kong cinema tradition that the action sequences are supervised by the action director and here that’s a little too obvious. Black Mask is a patchy film, with elements directed by three different people. Daniel Lee’s roving camera, Yuen Wo Ping’s tight action choreography, and producer Tsui Hark’s influence are all evident. It’s a talented trio, but their styles sometimes clash and the film never quite gels as a cohesive whole.

There’s no doubt that the explosive—often literally—action will be the main draw for most fans. However, for me, I would have enjoyed more time delving into the three key relationships. The buddy dynamic with Inspector ‘Rock’ Shek follows a satisfying though predictable pattern. Yeuk Laan’s mutual respect with Black Mask is more intriguing, as they share a past. Though it’s implied they can’t have romantic feelings, they both fail to kill each other when given the chance and even rescue each other on a couple of occasions. Their relationship is, as they say, complicated.

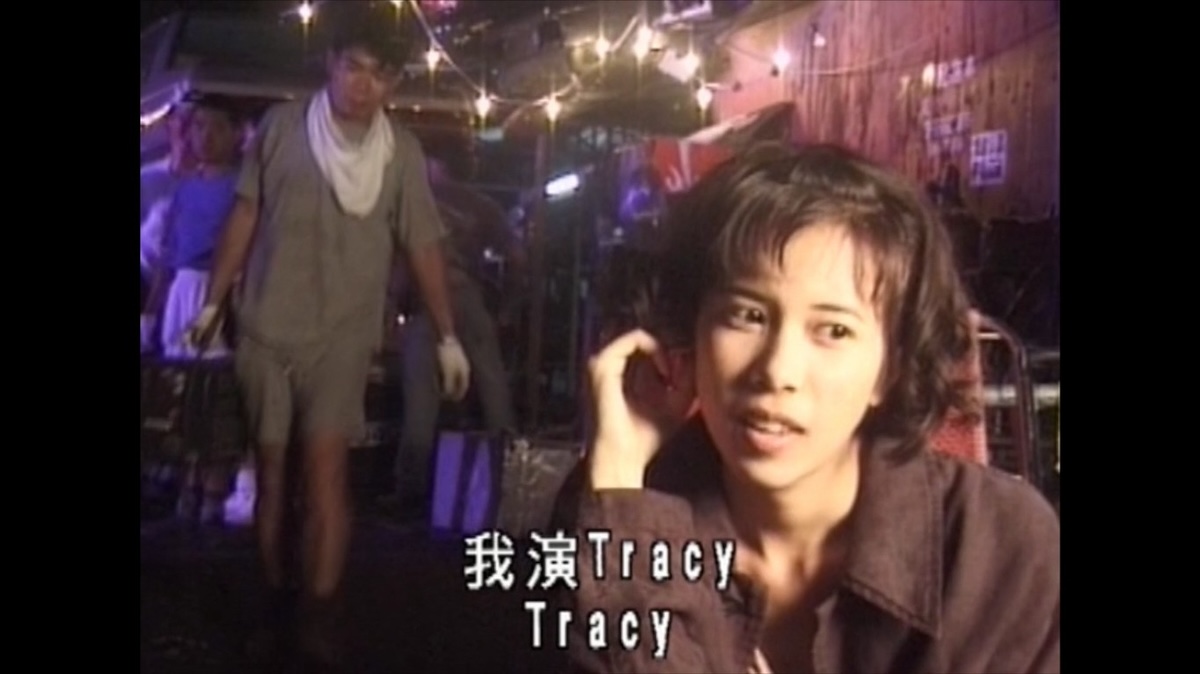

When Tsu Chik’s secret identity is inevitably compromised, he’s left with no choice but to rescue his innocent library colleague, Tracy (Karen Mok), who we know harbours feelings for him. As Black Mask, he keeps her captive at his secret lair, where he’s conducting experiments to reverse his super-soldier conditioning. Tracy soon realises he isn’t a threat and brings out his gentler side in a fun scene where they share a takeaway, and another where he talks to her on the phone as Tsu Chik. In turn, she shows her feisty side and becomes an unlikely accomplice to Black Mask. It’s a quirky romance that truly brings the characters to life, provides some light relief, and sets the film apart from many of its genre contemporaries.

There are rich subtexts to be mined, but they certainly aren’t foregrounded. Perhaps the most obvious is this: if one doesn’t recognise their own pain, how can they empathise with another or be sympathetic to the suffering of others? The nature of the neural adjustment the 701 Squad’s super-soldiers underwent is never made clear, but it seems that as well as making them unable to feel pain, it also rendered them incapable of processing grief, guilt, and remorse. They were made literally devoid of feeling.

In common with other cyberpunk predecessors that feature heroes who must resist the control of their corporate or military masters, those who are ultimately redeemed manage to delve deep and resurface an aspect of their humanity, rekindling their capacity to understand the feelings of others. This redemption comes about either through recognising those feelings within themselves, or at least, a desire to restore them.

HONG KONG | 1996 | 99 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | CATONESE • ENGLISH

director: Daniel Lee.

writers: Tsui Hark, Koan Hui, Teddy Chan & Joe Ma (story by Li Chi-Tak & Pang Chi-ming; based on the comic-book by Li Chi-Tak).

starring: Jet Li, Lau Ching-wan, Karen Mok, Françoise Yip, Patrick Lung, Anthony Wong, Xiong Xin-xin & Moses Chan.