X-MEN (2000)

In a world where mutants exist and are discriminated against, two groups form for an inevitable clash: the supremacist Brotherhood, and the pacifist X-Men.

In a world where mutants exist and are discriminated against, two groups form for an inevitable clash: the supremacist Brotherhood, and the pacifist X-Men.

Superheroes were in a sorry state by the late-1990s. Batman was the only comic-book franchise Hollywood took seriously, but that golden goose had floundered with the reviled Batman & Robin (1997). That same year, a darker take on superheroes arrived in Spawn (1997), but that adaptation of Todd McFarlane’s horror-inflected comic-book was a mess of subpar VFX and dull storytelling. However, a desire to treat superheroes with more seriousness was definitely in the air as a reaction against Batman’s perceived missteps.

Blade (1998) is often cited as paving the way for the comic-book genre that now dominates the blockbuster field, and it certainly left an impression on audiences and filmmaker that saw it. The Matrix (1999) also sold Hollywood on the idea of using superheroes as a means to explore more imaginative ideas now CGI was becoming cheaper. But it was X-Men (2000) that truly opened the floodgates to mainstream dominance, thanks to it being more accessible to people compared to its R-rated forebearers.

Having been a popular Marvel title since its publication in 1963, the idea of producing an X-Men film was first discussed in the early-1980s following the success of Superman: The Movie (1978). Comic-book writers Gerry Conway and Roy Thomas turned in a script for Orion Pictures in 1984, but when the studio encountered financial difficulties the project fell apart. Carolco was courted to take over the project by Marvel top brass Stan Lee and Chris Claremont, who hoped to hire James Cameron (Aliens) and Kathryn Bigelow (Near Dark) as a producer and director respectively. Bigelow even wrote a treatment and wanted to cast Bob Hoskins as Wolverine (yes, seriously) and Angela Bassett as Storm, but Carolco went bankrupt and the rights to X-Men reverted back to Marvel.

Far from the entertainment goliath they are today, Marvel immediately wanted to sell the X-Men rights on to Columbia Pictures, but producer Lauren Shuler Donner of 20th Century Fox nabbed them in 1994 after noting the popularity of 1992’s X-Men animated TV series. Andrew Kevin Walker (a year away from his breakthrough with Se7en) was commissioned to write a screenplay that pitted the X-Men against the Brotherhood of Mutants in a story that also involved the mutant-slaying Sentinel robots. His version was extensively rewritten by the likes of Laeta Kalogridis and Joss Whedon before Michael Chabon pitched a fresh idea entirely.

As the screenplay was undergoing development in the mid-1990s, up-and-coming directors like Robert Rodriguez (Desperado) and Paul W.S Anderson (Event Horizon) turned down the chance to work on X-Men. But a young director called Bryan Singer, who’d found success with The Usual Suspects (1995) and was expected to make Alien Resurrection (1997) next, was brought onto X-Men by producer Tom DeSanto, who thought the bisexual filmmaker was a better fit for X-Men because of its themes of social prejudice.

In 1996, Singer had signed on to X-Men but was busy working on his Stephen King adaptation Apt Pupil (1998), so the X-Men script was being further rewritten by Ed Solomon (Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure) ahead of an expected Christmas 1998 release. Chris Claremont then reentered the picture and saw Fox still struggling with the story, so he wrote a long memo outlining the core strengths and themes of the X-Men characters, which helped Singer enforce the parallels to real-life figures Martin Luther King and Malcolm X through the opposing figures of Charles “Professor X” Xavier and Erik “Magneto” Lehnsherr.

X-Men’s budget had been set as $75M, so Singer had to ditch a few ideas and characters that would have inflated it to $80M. Expensive characters like furry Beast and teleporting Nightcrawler were ditched, together with a big “Danger Room” action set-piece. Christopher McQuarrie (The Usual Suspects) came aboard to streamline the screenplay for budgetary reasons, but it was David Hayter who rewrote the whole thing encompassing many changes that had been made over the years. Hayer received solo credit on the final movie despite all the hands it passed through, partly because McQuarrie kindly refused the offer of a co-writing credit because he thought the final draft was more in tune with Hayter’s ideas than his own.

The most famous behind-the-scenes story of X-Men involves the casting of Wolverine. Russell Crowe (Virtuosity) was the first choice to play the fan-favourite character, but he turned it down and recommended his unknown Australian friend Hugh Jackman for the part. However, Singer opted for Dougray Scott (Ever After), only for the Scottish actor to exit the production because of a scheduling conflict on Mission: Impossible II (2000) where he sustained a motorcycle injury. Already three weeks into shooting X-Men in 1999, musical theatre star Jackman was hastily brought in as a replacement after a good audition. Oh, what might have been!

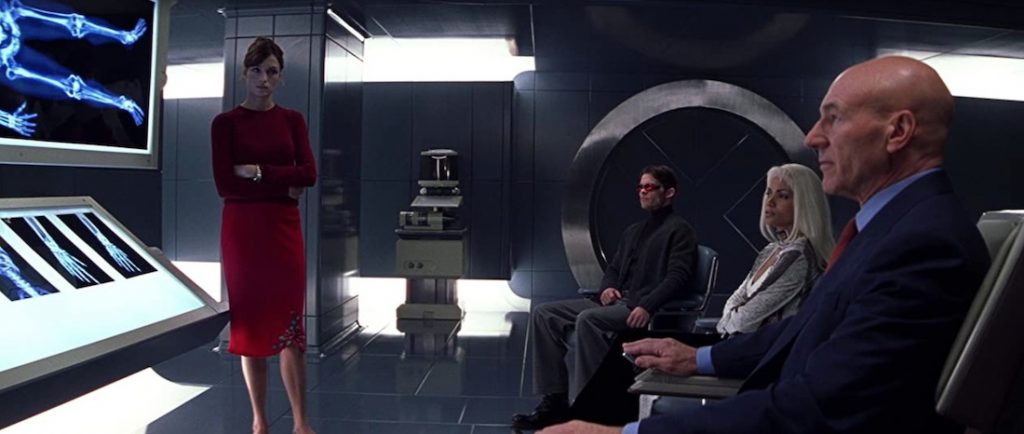

The rest of the cast was selected without as much drama: Patrick Stewart (Star Trek: The Next Generation) was the fan’s popular choice for Professor X and agreed to take the part; James Marsden became laser-eyed Cyclops after Jim Caviezel dropped out; Angela Bassett was still odds-on to play weather-controlling Storm, but Fox preferred Halle Berry because she was younger and cheaper; Natalie Portman turned down power-stealing Rogue and so the part went to Anna Paquin (The Piano); Peta Wilson would have been psychic Jean Grey if she didn’t have to shoot the fourth season of Le Femme Nikita, so she was replaced by Famke Janssen (Goldeneye); model Rebecca Romijn-Stamos underwent six-hours of make-up to play blue shapeshifter Mystique; and renowned thespians Christopher Lee and Terence Stamp (Superman II) were considered for villainous Magneto, but Singer wanted his Apt Pupil star Ian McKellen.

Filming began on 22 September 1999 and ended on 3 March 2000, with Singer having to get X-Men ready for cinemas by 14 July because Fox needed a big movie to replace Minority Report (2002) because Steven Spielberg had decided to make A.I Artificial Intelligence (2001) instead.

One notable change X-Men made was with the costuming, as the characters in the comic-books each wear different brightly coloured clothes. It was felt the X-Men had to have more subdued matching black costumes to give them a sense of cohesion as a team, prompting one memorable joke in the film when Wolverine complains about their leathers and Cyclops responds “what would you prefer, yellow spandex?”

Seeing X-Men again today, decades after it triggered the superhero-saturated media landscape we’re living in, is an interesting experience. I distinctly remember feeling underwhelmed by the action, even back in 2000, so that criticism has only doubled now we’re so accustomed to enormous spectacle far beyond X-Men’s budget and turn-of-the-millennium expertise. But there’s a focus on character and a sort of low-key earnestness that’s rather pleasant, as it’s less of an excuse for VFX and more of a character-based adventure aiming to quietly introduce audiences to a new universe of possibilities. The result is that casual audiences were intrigued to see more from these fantastical heroes and villains, while dyed-in-the-wool fans were pleased it took X-Men’s themes seriously. Both crowds were excited by the potential of a sequel with more money behind it.

The opening act of X-Men is still a masterclass in getting audiences clued up on a big new idea, with the flashback to 1944 Poland where a young ErikLehnsherr’s ability to control metal is awakened by his experience in a Nazi concentration camp. Just the idea of putting superheroes in a backdrop associated with harrowing dramas like Schindler’s List (1993) makes this sequence stand out, and it primed audiences for a different kind of film to the camp nonsense of Batman & Robin. And even the jump to the present-day with Rogue (Paquin) accidentally killing her own boyfriend by innocently kissing him perfectly explains how life as a mutant is difficult and frightening, with the obvious analogue to puberty and teenage angst.

By the time we’ve met Wolverine (Jackman) as a dispirited cage-fighter earning beer money by beating up Canadian truckers, we’re sold on the idea of a world where mutants are a mysterious new species coming to widespread attention. A lot of X-Men is simply about explaining this ‘us and them’ social dynamic, with Senator Kelly (Bruce Davison) as an anti-mutant campaigner intent on banning mutant kids from schools. Kelly represents a challenge mutants are split on how to handle appropriately, with Professor X (Stewart) preferring to alleviate human concerns that mutants are a danger to people, while his old friend Magneto (McKellen) takes a more aggressive approach and hatches a plot to mutate the world’s leaders at a United Nations event.

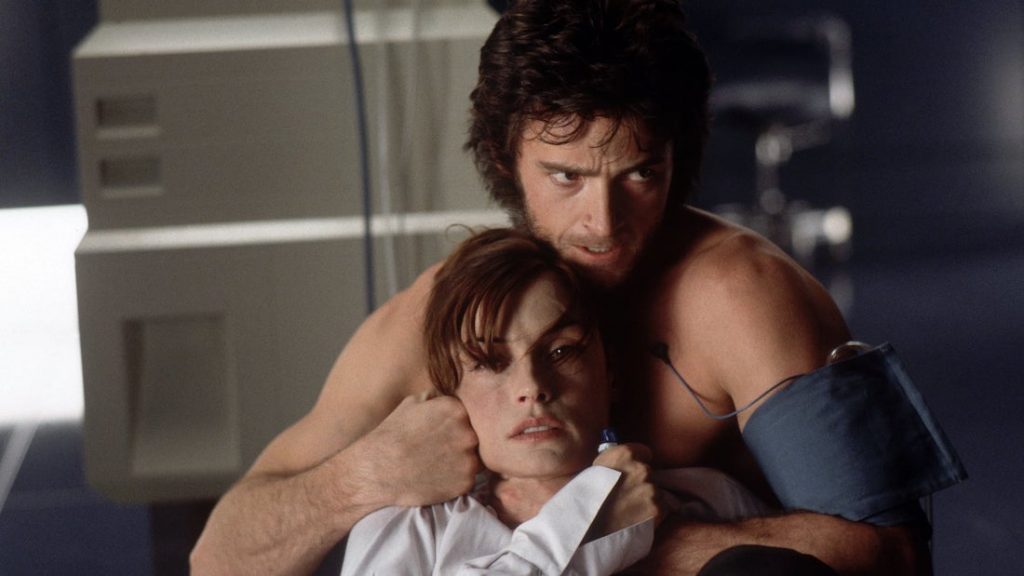

Considering the opposing views of Professor X and Magneto is a real cornerstone of X-Men lore, and fuels much of the drama in the sequels, it didn’t feel as central in this movie as I’d remembered. Stewart and McKellen don’t actually share many scenes together, although this is where those two actors met and began a strong friendship. The emphasis is more predictably on Wolverine, who was always the most popular character and works as the audience surrogate as he’s shown the curious world of Professor Charles Xavier’s School for the Gifted and how it doubles as a superhero training HQ. Rogue’s also a useful character for him to take under his wing, as she essentially turns him back from a life of selfishness and isolation to being a team player who values his new friendships.

Jackman certainly had a lot resting on his shoulders with X-Men, but he’s a remarkable screen presence from the beginning. Any concerns fans had over petty things like his height (Jackman’s a tall 6’2″ and Wolverine is supposed to be a squat 5’3″) quickly melt away, such is his innate charisma and gruff persona. He’d certainly portray the character more effectively in later films, particularly his gritty swansong Logan (2017), but Wolverine still steals the show from under the noses of more established actors here.

It’s also fun to see how young everyone looks, too. Even Stewart and McKellen look comparatively youthful, despite both being in their early sixties at the time. There’s a sharpness to their features and strength to their body language that’s more noticeable a few decades later, as both are now in their eighties. Magneto is more of a threat and cold-hearted adversary just to look at, with the sequels turning him into more of a meddling old man audiences love-to-hate.

There are certainly many weaknesses to X-Men, which were obvious at the time and compounded today. For instance, there’s a weak lineup of henchmen for Magneto in dull Sabretooth (Tyler Mane) and silly Toad (Ray Park). Plus there are some awful lines of dialogue—like Storm’s infamous “do you know what happens when a toad gets hit by lightning?” zinger. The portentousness of the opening flashback to a concentration camp is also never echoed in the present-day drama, as it all becomes quite tame and silly. And the action sequences ring a little hollow and don’t build up much momentum, meaning it’s a rare comic-book film where the best moments are the quiet moments of character introspection!

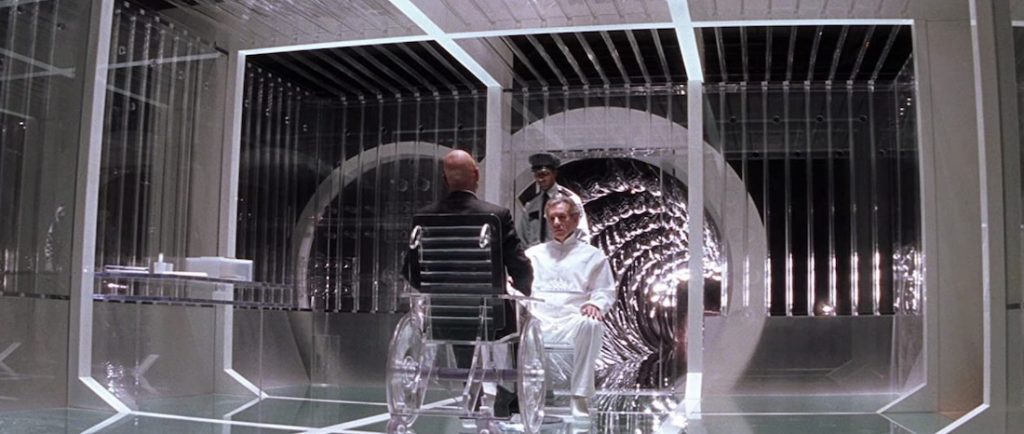

But what X-Men did perfectly was present an intriguing alternate world that made audiences hungry for more, and the casting was exemplary—although I think we can all agree Angela Bassett would’ve been a better choice for Storm, and worth the extra money. John Myfre’s production design also proved to be enduring, as important sets like Xavier’s school and the Cerebro chamber didn’t get tweaked in any of the subsequent X-Men movies and spin-offs. It got a lot of important designs and details correct at the start and surprisingly little was overhauled.

The film’s world premiere was held at Ellis Island (one of the locations in the climactic set-piece) on 12 July 2000 before opening wide in North America a few days later. It grossed $157M in the US and ultimately earned $296M worldwide, making it the eighth highest-grossing film of 2000. At the time it also broke the record set by Batman Forever (1995) for the highest-grossing weekend for a superhero film, taking $54.5M to Batman Forever’s $52.7M. The reviews were mostly favourable and X-Men’s success led to two direct sequels—X-Men 2 (2003) and X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) —a spin-off trilogy for Wolverine, and four prequels with a younger cast that all exist within the same canon.

Of course, X-Men made a superstar of Hugh Jackman and turned Ian McKellen into a household name (although The Lord of the Rings also helped in that), and for a while, director Bryan Singer became a big name in Hollywood. However, that ended in 2019 when allegations of sexual misconduct arose while Singer was shooting Bohemian Rhapsody (2018). These weren’t the first time allegations had been made against him during his career, but occurring during the #MeToo movement finally made him a pariah. And considering X-Men’s themes of tolerance and acceptance of all people despite their differences (which Singer seemed well-placed to champion due to his bisexuality), it’s disappointing to see these sorts of compelling allegations arise about his behaviour.

X-Men kickstarted the superhero films of the 21st-century, undoubtedly helping Spider-Man (2001) to become an even bigger success. And its superior sequel in 2003 helped lay the groundwork for Marvel Studios’ dominance since Iron Man (2008). And now that 20th Century Fox has been bought by Walt Disney Pictures, who own Marvel Studios, there’s every chance the X-Men will return for a whole new generation to enjoy very soon.

USA | 2000 | 104 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Bryan Singer.

writer: David Hayter (story by Tom DeSanto & Bryan Singer, based on ‘X-Men’ by Stan Lee & Jack Kirby).

starring: Patrick Stewart, Hugh Jackman, Ian McKellen, Halle Berry, Famke Janssen, James Marsden, Bruce Davison, Rebecca Romijn-Stamos, Ray Park & Anna Paquin.