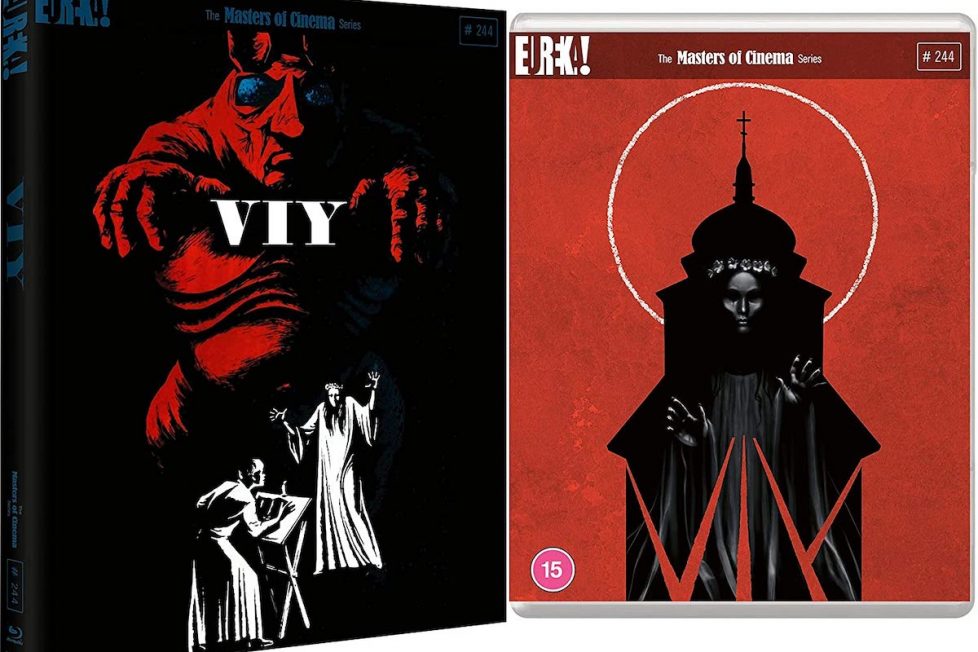

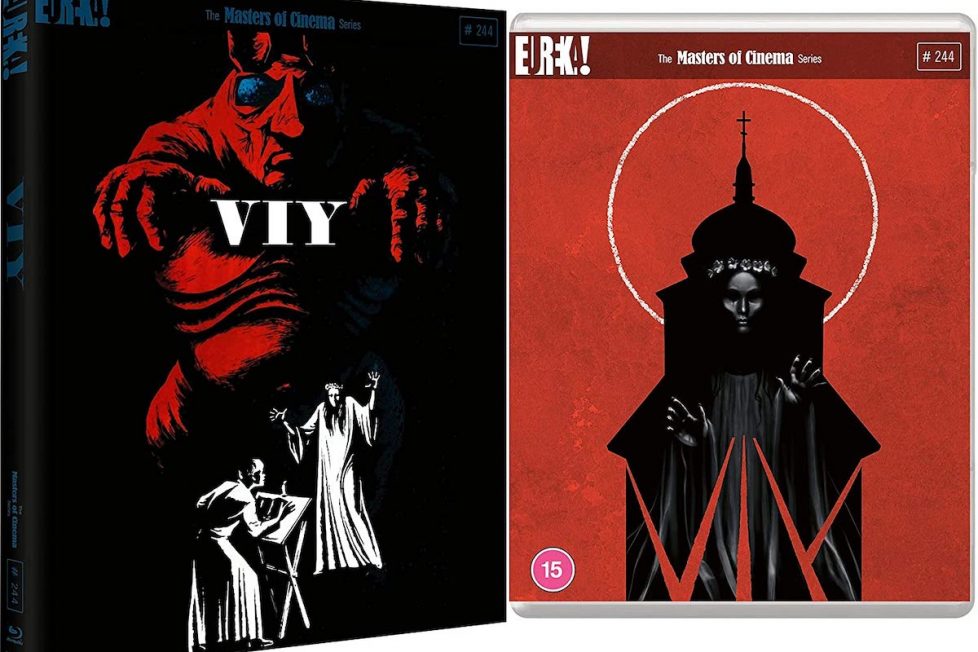

VIY (1967)

A young priest is ordered to preside over the wake of witch in a small old wooden church of a remote village.

A young priest is ordered to preside over the wake of witch in a small old wooden church of a remote village.

This new Viy Blu-ray package is a delight for anyone interested in Soviet and post-Soviet cinema of the imagination, not to mention those intrigued by Ukrainian literature and folklore. Niche? Perhaps. But I, for one, eagerly anticipated the latest addition to Eureka’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ imprint, and it doesn’t disappoint. Spread over two discs are two important interpretations of Nikolai Gogol’s classic tale of the supernatural, Viy / Вий (1967) and Sveto Mesto / A Holy Place (1990), plus a host of worthwhile extras, including surviving fragments from three more ‘lost’ silent films with historic relevance.

This is the earliest surviving film version of Gogol’s famous folk horror story. Viy‘s ingrained in the Russian consciousness as indelibly as Dracula in western Europe. It seems to have been remade and reinterpreted just as often—more recently with a heavily embellished 2014 version that broke Russian box office records, and again for TV in 2018. An earlier 1909 silent version, sadly lost, had been directed by Vasily Goncharov, an important pioneer of Russian cinema. His work faded into relative obscurity following the February Revolution of 1917, which ended Imperialist Russia and began the Soviet era. In the drive to establish a new regime, stories and styles associated with the past were shunned in favour of the new Socialist Realism. With the exception of science-fiction, which helped to visualise possible futures, anything with fantastical elements became a rarity. Horror and fantasy all but disappeared from mainstream Russian culture… until Viy reintroduced the genre in 1967… with a vengeance!

Bringing Viy to Soviet screens in the late-1960s, at the peak of the Cold War, was a process beset with political and practical pitfalls. It ended up in a different creative place to where it began and, in some ways, can be approached as a collage of more than one movie. Thinking of it as a kind of portmanteau enhances rather than detracts from its considerable viewing pleasures. This clash of styles is, after all, what makes the transition from real world into fantasy realm all the more abrupt and surprising when it occurs at the mid-point.

Viy, sometimes known as Spirit of Evil, began its problematic production as a student-helmed project with a screenplay by Konstantin Ershov and Georgiy Kropachyov who were to co-direct. They’d managed to get their proposal past the state censors by couching it as an attempt to reclaim Gogol for Russia. They believed action had to be taken after western filmmakers had so crassly disrespected his most popular tale in the form of The Mask of Satan (1960), Mario Bava’s superior, though somewhat tenuous, reworking of the same source material.

However, part-way into production, Mosfilm Studios weren’t happy with how things were progressing and suspended the project. The script was reworked and the concept turned on its head. All this remains evident on the screen with the first half being patchy at best. Some of the lighting is reminiscent of British teleplays from that time—obvious multiple shadows from studio lights or rather bland ambient light. Given that Andrei Tarkosvsky had already set the bar for Soviet cinema with Ivan’s Childhood (1962) and Andrei Rublev (1966), there’s really no excuse!

However, there are some gorgeous interludes here and there. I particularly enjoyed the naturalistic softness of the exterior landscapes. Cinematographer Viktor Pishchalnikov seems to relish these, too, arranging the figures in harmony with the features of the land or placing them in the fore yet dwarfed by a vast panoramic vista, fading into mist.

It’s apparent that the script is crippled by a propagandist remit that treats the Cossacks, clerics, and peasants, with open distain. They’re all blustering drunkards, arrogantly self-serving, or cowardly simpletons. It’s almost a send-up of ‘Old Russia’ and pretty much aligns the Orthodox religion with any other form of outdated superstition, before ridiculing it further for its double standards and ultimate impotence. There are a few moments among the priests at the seminary school that could be outtakes from the Soviet version of Father Ted!

But the unevenness of the first half is more than made-up for by the cast and their gutsy portrayals of the uncouth clergy and course Cossacks. We first meet Khoma (Leonid Kuravlyov) and his two priestly pals, Gorobets (Vladimir Salnikov) and Khalyava (Vadim Zakharchenko), as they’re let loose from seminary school at the end of term. After stampeding through the local market with their fellow students, stealing geese and groping young women in a most impious way, they head off to their village across rugged moorlands. A storm brings on the night sooner than expected and they fail to find the road they’re looking for. Instead, they come across an isolated and ramshackle farm where an old woman (Nikolay Kutuzov) agrees to let them shelter.

Sleeping in the barn, Khoma’ assaulted by the old woman who’s not only a lot stronger than she aught to be but has supernatural powers enough to overcome the young man and mount him! The night-hag rides him like a horse above the trees in a disconcerting VFX sequence until they fall back to earth, exhausted. The horrified Khoma seizes his chance and retaliates, viciously beating the old woman to death. This is the first scene we see that’s been added by Aleksandr Ptushko, effectively the third and most important director to work on the film, responsible for some of the most beautiful and painterly compositions throughout.

Clearly, this dreamlike sequence is a metaphor and plays with all sorts of conflicting notions: age and youth, old religion versus the new, sadism and masochism, sex and death. Pretty much the standard fare of folk tales and old fairy stories! It also questions binary gender as the old woman is initially played by a man, throwing in homophobia on top of the usual witchy misogyny. However, as she lay dying, the hag changes into a young beauty (Natalya Varley), and only then does Khoma feel remorse and runs back to the sanctuary of the seminary.

Shortly after, the Rector (Pyotr Vesklyarov) receives news that the local Lord’s daughter was found terribly beaten by an unknown assailant and her dying wish was that Khoma be sent to pray for her. It’s a mystery to the Lord and the Rector how the young noblewoman could know of Khoma by name… Khoma, of course, has his suspicions and refuses. Under threat of a good leathering from the Rector he’s handed over to the Lord’s men who are waiting outside to escort him, led by the formidable Dorosh who, in a nice twist of meta-casting, is also played by Vesklyarov, unrecognisable without the huge orthodox beard of the Rector. Instead, he now sports the drooping moustache and top-knot of a Cossack as portrayed in classic book illustrations for Viy.

When Khoma finally meets Lord Sotnik (Aleksey Glazyrin) he learns that he’s arrived too late to perform the last rites and must now pray for the salvation of her departed soul. He tries once more to back out but is again threatened with a whipping if he doesn’t comply. Sotnik senses something is awry and knows that his daughter’s dying wish must be some form of retribution for the priest, who must now be locked in the decrepit, obviously neglected, church with her body from dusk till dawn for a three-night vigil.

When dealing with the dead, the film really comes alive and completely changes character. Effectively, creative control had now been wrested from the nominal directors and handed over to legendary Soviet special effects maestro Aleksandr Ptushko, who’s been described as Russia’s answer to Ray Harryhausen. We saw his influence begin to edge its way in with the earlier flying sequence. Now in the wonderful church interior set, designed with Nikolay Markin, Ptushko brings his years of experience to bear with an array of ingenious effects combining every technique at his disposal.

Central to these memorable church sequences is an early appearance for Natalya Varley as the undead daughter and although it’s not a speaking part (her minimal dialogue was overdubbed by Nadezhda Rumyantseva) her physical performance is a highlight. She’d trained as a trapeze artist and does her own somewhat ambitious stunts here. Despite her circus skills, she was almost killed when one of the frenetic ‘coffin-surfing’ scenes went wrong. She gets a bit ‘Kate Bush’ at times, which for me is a plus point, and is joined by an increasingly weird array of otherworldly beasties and demons. These nightmarish scenes draw from the imagery of Francisco Goya’s ‘Black Paintings’ as did Benjamin Christensen’s silent horror classic Häxan (1922) to which I believe Viy owes a great visual debt.

Ptushko rewrote the final act and brought his own production team with him including his favourite cinematographer, Fyodor Provorov, and a band of specialist puppeteers and performers. There’s a clever mix of in-camera trickery, inventive costumes and puppetry, miniature effects that play with perceptions of scale, rear-screen processes and ground-breaking post-production composites.

Night one is a fairly modest sequence except for some frenetic camera choreography which at times swirls around the action in dizzying 360-degree sweeps. Nights two and three ramp-up the supernatural onslaught into a crescendo that puts the similar finale of The Devil Rides Out (1968) to shame. By the time the titular spirit of evil shows up, the audience of the day must’ve been reeling with shock and awe.

The final act is as weird and wonderful as anything found in a classic Hammer or Corman movie. I loved the folkloric backdrop and everything that occurs the cursed church during Khoma’s three-night vigil and, really, the rest of the film is just a way of getting us there. However, it never manages to gel into a cohesive whole and can’t settle on whether to compete with its contemporaries in the horror genre, be a political satire, a Rabelaisian comedy, a fairy tale… Instead, it ends up being an uneasy mix of all those things, which I suppose is some kind of achievement in itself!

SOVIET UNION | 1967 | 77 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | RUSSIAN

The second feature in this double-bill, starts out just as faithful to Gogol’s original story. Some of the scenes and dialogue are near matches though the atmosphere is more subdued and grimmer from the start. The first marked difference is the animalistic ferocity, of the old woman’s attack upon the young priest, Toma (Dragan Jovanovic). It’s far more intense and nightmarish than the man-hag of Viy, for whom we could feel some sympathy. From that point on, Sveto Mesto / A Holy Place begins to veer off along its own path to explore themes that would’ve been just too transgressive for the sixties. They were darn ‘close to the bone’ for the 1990s and may well shock the more politically correct among audiences nowadays. But Serbian writer-director Djordje Kadijević‘s no stranger to controversy having caused a stir straight off the bat with his debut The Feast (1967), coincidentally released the same year as Ptushko’s Viy.

Kadijević was a war veteran who had fought as a partisan against the Nazi forces in German-occupied Yugoslavia. He’d witnessed atrocities and seen man’s inhumanity to man and this affected his output as an artist. The Feast had been the first in a series of tragic war dramas that don’t end well for the protagonists. He became associated with the Yugoslav-Serbian ‘Black Wave’, made up of a group of avant-garde auteurs that also included Dušan Makavejev who had to flee the country after his infamous political satire WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971) was banned by the Communist censors.

The state also disapproved of Kadijević’s early war films because they showed the Slavic people behaving unscrupulously, their moral fibre tested by deprivations of war, and portrayed the German forces as terrifying, formidable adversaries. He found it impossible to continue making films that spoke his truth. So, he changed tack and made A Virgin Concert (1973), a Gothic mystery horror, and Leptirica / The She-Butterfly (1973) inspired by After Ninety Years, a folktale of vampirism and shape-shifting written by a nineteenth century Serbian author, Milovan Glisic.

At the time, simply stepping away from Socialist Realism was an act of rebellion and with supernatural horror, Kadijević found he could still address darkly soul-searching psychological material. He became known for horror and historical dramas, mainly made for state television, though he found it increasingly difficult to make any films against the political turmoil of the 1980s and Sveto Mesto was to be his return to cinema after a hiatus of seven years. As it turned out, the political tensions escalated to armed uprisings and conflicts between the states that comprised Yugoslavia. Rivalry between Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina was constantly in the world news and there was no interest in domestic cinema at the time, particularly Gothic horror. Sveto Mesto couldn’t attract a distributor and faded into obscurity.

This is a far darker reworking of Viy and though it remains true to the original themes of Gogol’s folktale, it takes them to greater and more explicit extremes. The story remains a simple one, but the extra runtime is justified by deeper character development and the inclusion of vignettes illustrating the stories retold by the characters. Some of these tales are obviously embellished in the recounting. Others appear to be flashbacks, adding greater complexity to their backstories. Just like the protagonist, Toma, we are left to judge the reliability of the different narrators as things get stranger and rumours of cruelty, incest, and devilry become increasingly believable.

This time round, the undead ‘witch-girl’, Katarina (Branka Pujic) is a less sympathetic character who, whilst still portrayed as a victim, has certainly made a deliberate choice to perpetuate the abuse she’s suffered in life. We also have a different version of our protagonist. In the earlier film, the priest is unrepentant for murdering the witch—after all, isn’t that what the church did as a matter of course! He’s presented as an orphan who joined the priesthood to keep a roof over his head and food on the table and clearly has not heeded any ‘calling’ and this lack of faith proves to be his undoing.

The hapless clergyman in Sveto Mesto seems to make a genuine effort to redeem the soul of Katarina, the damned dead girl, but his undoing weakness is one of gendered psychology rather than absence of belief. Probably the biggest difference between the two versions here is that Viy is actually a great deal of fun and the retro effects are a magical joy to behold! Whereas Sveto Mesto is unrelentingly grim with a conspicuous absence of visual effects. Ultimately, the real horror is of human, rather than supernatural making… even Viy refuses to show-up, which explains the change of title.

The incestuous relationship between the Lord and his daughter is barely hinted at in the first movie. There’s even a chance he’s being manipulated himself by the spirit of his dead wife with underlying hints of vampiric possession. This time, nobleman Gospodar Zupanski (Aleksandar Bercek) is a much creepier character and definitely the villain of the piece. This is confirmed when we finally see the highly inappropriate full-length, life-size portrait he’d had commissioned of Katarina. Another painting plays a prominent plot point here, too, as it becomes apparent that the portrait of his late wife, Gospodarica (Mira Banjac) is indeed haunted.

Perhaps this is what brought to mind the similar ominous atmosphere of Leslie Megahey’s memorable arthouse horror, Schalcken the Painter (1979), along with the shared theme of necrophilia. And maybe, the overt lesbian subtext is what reminded me of Harry Kümel’s Daughters of Darkness (1971). Throw in the ponderous melancholic beauty of Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) and you’ll have a pretty good idea of what you’re getting into when you sit down to watch Sveto Mesto, which really deserves to be talked about just as much as those three classics.

YUGOSLAVIA | 1990 | 90 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | SERBO-CROATIAN

directors: Konstantin Yershov & Georgi Kropachyov.

writers: Aleksandr Ptushko, Konstantin Yershov & Georgi Kropachyov (based on the novella by Nikolai Gogol).

starring: Leonid Kuravlyov, Natalya Varley, Alexei Glazyrin, Vadim Zakharchenko & Nikolai Kutuzov.