Karloff in Maniacal Mayhem (1936-1951)

Eureka reissues three Boris Karloff movies from the late-1930s to the early-1950s: The Invisible Ray, Black Friday, and The Strange Door.

Eureka reissues three Boris Karloff movies from the late-1930s to the early-1950s: The Invisible Ray, Black Friday, and The Strange Door.

The B Movie screenwriters of Hollywood’s Golden Age were adept at ringing the changes on tried-and-tested formulae to create storylines that, if not quite fresh, at least offered some novelty value. Thus, in this collection of three Boris Karloff movies from the mid-1930s to early-1950s, The Strange Door (1951) blends the trappings of a costume adventure with a horror atmosphere, and even includes a barroom brawl straight out of a western, complete with chandelier-swinging. The Invisible Ray (1936) begins as a Frankenstein-style horror tale before becoming out-and-out science-fiction, a rarity for the era; and Black Friday (1940) is a crime drama with elements of noir, sci-fi, and psychiatry—a popular theme at the time.

Of course, the sheer number of such films necessitated that the same elements were revisited again and again. So the genius in The Invisible Ray resentful of others for stealing his work bears a resemblance to Karloff’s inventor in Night Key (1935), just as the French chateau in The Strange Door does to the German Schloss of The Black Castle (1952). (Both those films are on Eureka Entertainment’s Universal Terror collection.) The brain-transplant premise of Black Friday, meanwhile, was a favourite topic, particularly with co-writer Curt Siodmak; several of the movies dealing with it, though not this one, were based on his novel Donovan’s Brain.

Covering almost exactly the same years as the Universal Terror release, these three films highlight the marketability of Karloff and his changing place in the Hollywood hierarchy. In the earliest of the three, The Invisible Ray, he’s so much the star that the credits simply state ‘Karloff and Bela Lugosi’; it came out only a year after the acclaimed Bride of Frankenstein (1935). But it was the last occasion on which Karloff would be billed by his surname alone, and by the time of The Strange Door he’s billed lower than Charles Laughton, despite the latter’s major successes being more than a decade earlier.

Karloff’s frequent co-star Lugosi, meanwhile, plays second fiddle to Karloff in two of these films, as he so often did; his role in The Invisible Ray is at least an important and sympathetic one, but in Black Friday he exists solely as a cog in the plot and has no meaningful interaction with the Karloff character. Still, getting both names on the poster together must have helped at the box office, and the original plan was for Lugosi to have a bigger part.

All three movies are rather bloodthirsty (discreetly so, given the Hays Code) but two of them—Black Friday and The Invisible Ray—also explore interesting ideas. Black Friday is the best of the trio, not least thanks to an outstanding performance in a double role by the last-minute hire Stanley Ridges (who replaced Karloff when the latter decided he preferred to play another character).

The Strange Door is the least successful as a film: little more than an exercise in creaky silliness, with Karloff’s skulking lackey exuding a distinctly Carry On air. He is not, in fact, the best thing about any of the films, but they all have other strengths.

A brilliant scientist’s discovery of a miraculous new element leads to medical advances… and then to murder.

The dark and stormy night in Carpathia that opens The Invisible Ray might suggest horror is to come, but then blind old Mother Rukh (Violet Kemble Cooper) recalls “it was on such a night that Janos first caught his ray from Andromeda”; and indeed we’ve already been promised, in an opening title, that the film will deal with “a theory whispered in the cloisters of science”.

Presumably, the theory was only whispered about because it was so preposterous, but The Invisible Ray at least pretends that it makes sense when the cloak-clad Dr Janos Rukh (Karloff) summons two eminent scientists—Dr Benet (Lugosi) and Sir Francis (Walter Kingsford)—to his Carpathian lair so he can explain his discovery.

They duly arrive along with Sir Francis’s wife Lady Arabella (Beulah Bondi) and young Ronald (Frank Lawton), who might as well have ‘Romantic Interest’ stamped on his forehead since his visit serves no other apparent purpose, and are soon observing as Janos uses a gigantic telescope-like device to catch a ray from the Andromeda Nebula (as it was then known).

This ray is then “electrically transferred” to a projector, and in some not-very-comprehensible way that’s quickly brushed over but must be very scientific because it involves “electric magnification”, the ray allows the party to view—as if from space—an occurrence in the distant, pre-human history of the Earth: a meteor hitting the continent of Africa. They can even hear the subsequent explosion, which makes it a pretty impressive ray, all things considered!

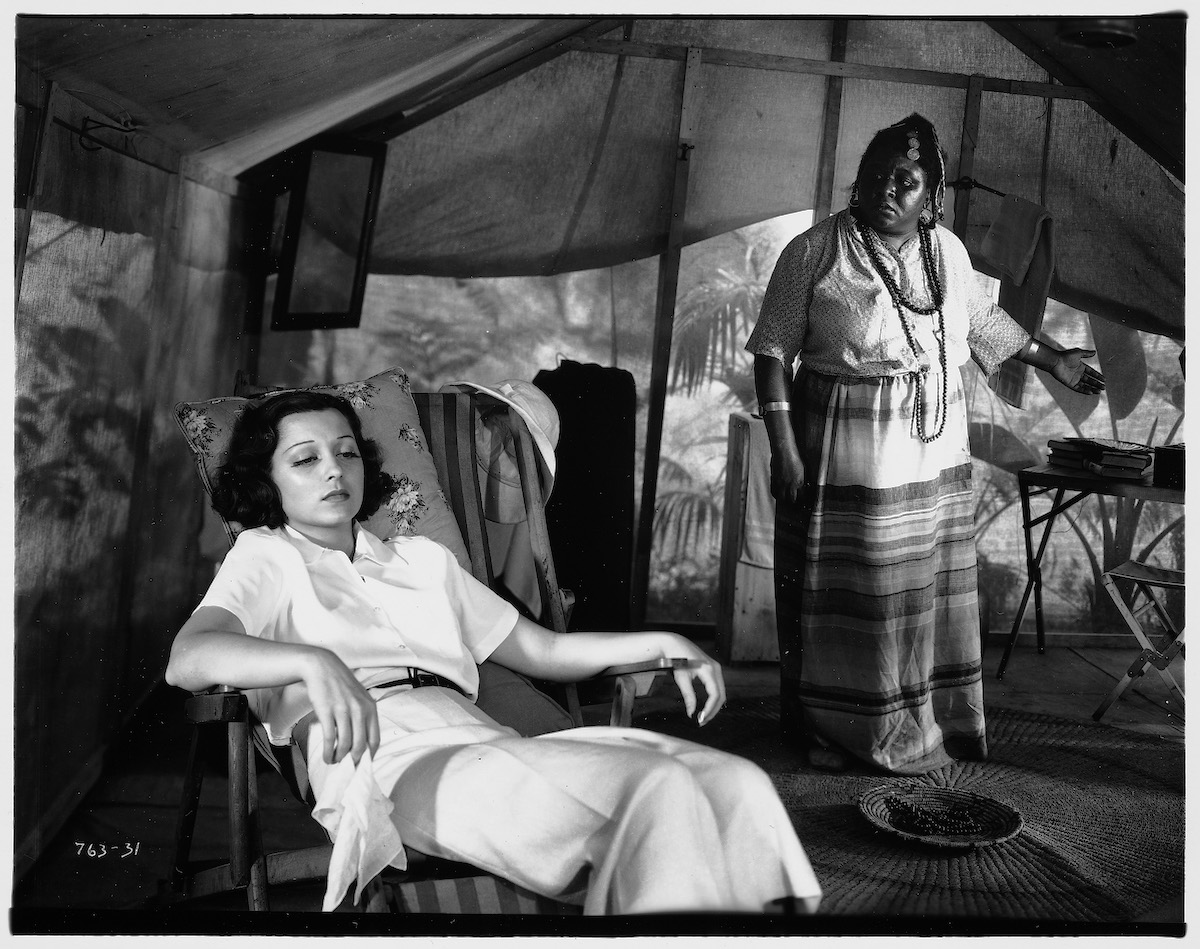

The scientists now resolve to mount an expedition to the meteor impact site in Africa; Mother Rukh warns Janos not to go but he doesn’t listen, even if the audience gets the message that he should. Before long, the group are in the Dark Continent, wearing solar topees and bossing around the natives, who prefer loincloths and bone necklaces. Some of Janos’s companions amuse themselves by hunting rhinos and leopards, but he’s busy taking samples of a new element brought to Earth by the meteor.

This element, Radium ‘X’, allows him to dissolve a rock outcrop (and later will also have strong curative properties); in fact, it gives him “more power than man has ever possessed”, the increasingly unhinged Janos gloats. “I could crumple up a city a thousand miles away… I could destroy a nation… all nations,” he says. Either a very prescient point for 1936 or simply a striking coincidence, given the involvement of radium in the development of the atomic bomb a decade later.

The downside is that Janos starts to glow in the dark and kill everything he touches. Even that, though, has its benefits when he becomes enraged that the others are profiting unfairly from his discovery, and travels to Paris to hunt them down.

The Invisible Ray is shot with style by George Robinson, cinematographer of a huge number of mostly forgotten pictures, and employs several ingenious effects: almost-invisible smoke coming off Karloff, for example, or a scene where statues of the saints outside a Paris church are briefly transformed into the six members of the Africa expedition. There is much use of mocked-up newspaper and magazine pages, too, to give the story verisimilitude (a technique also employed in Black Friday).

Male scientists drive the plot, but it is the women who convince most among the cast, especially Frances Drake as Janos’s wife and Kemble Cooper as his mother; May Beatty is droll in a much smaller role as an English landlady rather implausibly living in Paris. Lugosi is credible too as the honourable Dr Benet, but Karloff’s performance is mostly standard-issue mad scientist. The score by Franz Waxman is a cut above many B Movies’.

USA | 1936 | 80 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

An operation on a dying man’s brain inadvertently sets a dangerous criminal loose.

Black Friday appeared as film noir was just starting to emerge, but its tendencies in that direction are apparent from the opening scene, set in a prison where Dr Ernest Sovac (Karloff) is about to be executed. As he’s led to the electric chair, he gives to a reporter his “notes on the case of George Kingsley”, and then almost the entirety of the movie is a flashback to that case.

Kingsley (Stanley Ridges) is the archetypal mild-mannered, slightly scatty English professor, and a good friend of the surgeon Kovac. When the professor is injured in an accident involving the gangster Red Cannon (also played by Ridges) and seems likely to die, Sovac decides to save him by transplanting part of Cannon’s brain into Kingsley.

This operation might deeply mystify the audience for much of the movie, since at first (probably through a screenwriting oversight) we’re allowed to assume the whole brain has been transferred, making it rather surprising that Kingsley retains any of his previous identity. But he does.

What is less surprising, of course, is that the thoughts and memories of Red Cannon also now surface in Kingsley’s mind and before long the sweet professor is undergoing Jekyll & Hyde-style transformations into the ruthless criminal, in which his hairstyle, as well as his manner, are spontaneously transformed.

Though Sovac never intended this, he soon sees an opportunity: perhaps what survives of Red Cannon’s brain will recall where he has hidden his stash of (presumably ill-gotten) money, which would come in handy to fund a new medical institute.

Some intriguing questions are raised in Black Friday, and though the film never fully explores them, they provide a certain depth. Has Sovac given the professor a new brain, or the gangster a new body? Which is the real “self” now—can they co-exist? And is Sovac himself greedy (endangering his old pal Kingsley to get his hands on the cash), or simply reckless yet ultimately well-motivated (doing it all in the interests of medicine)?

Originally Lugosi was to play Sovac, with Karloff as Kingsley and Red Cannon; at the last moment Karloff decided he would prefer to be yet another unhinged man of science, and so the little-known Ridges was drafted in as the unfortunate brain donor and recipient.

Though he was never a star, he is superb in both roles (rather reminiscent of Kevin Spacey when in Red Cannon mode); Karloff, though, does nothing he hasn’t done before, and Lugosi is wasted in an uninteresting part as one of Red Cannon’s fellow criminals. John Kelly contributes an amusing cameo as a talkative cab driver, and Anne Nagel is strong as the gangster’s former girlfriend.

One of the best scenes, indeed, comes when “Red” visits her in her apartment. He’s in the professor’s body, of course, and so she doesn’t recognise him, but the transplanted brain remembers where everything is, and then she is horrified when he gives her a gift: a watch she knows was in the possession of a man he’s just murdered.

It’s a small scene, but one that succeeds very well in communicating through action rather than dialogue, and confirms that Black Friday is rather smarter than the average potboiler.

USA | 1940 | 70 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

A young 18th-century couple attempt to escape from the wicked French nobleman who is holding them captive.

The great Charles Laughton gets top billing in this Robert Louis Stevenson adaptation and dominates every scene he’s in, as well as the grand rooms of the sound-stage castle where most of it’s set. Karloff is mostly relegated to lurking in the cellars.

Like all three movies with their short running times, The Strange Door plunges straight into its narrative. The sign of a hostelry, Le Lion Rouge, tells us we are in France; horses pulling a carriage, and then Laughton in a tricorn, indicate the 18th-century.

He enters the establishment, where two other men point out to him a younger fellow at the bar, flirting with a woman. “He’ll do very nicely,” says Laughton (a line which could easily be interpreted in a different way, given the way that the English actor camps things up in the extreme for the entire film).

This young man, Denis de Beaulieu (Richard Stapley), is soon framed for an apparent murder engineered by Laughton and his cronies and is fleeing for his life across the countryside with a posse in pursuit. He comes across a door; not a particularly strange one but—it transpires—certainly an unwise one to enter because once through he finds it locked behind him.

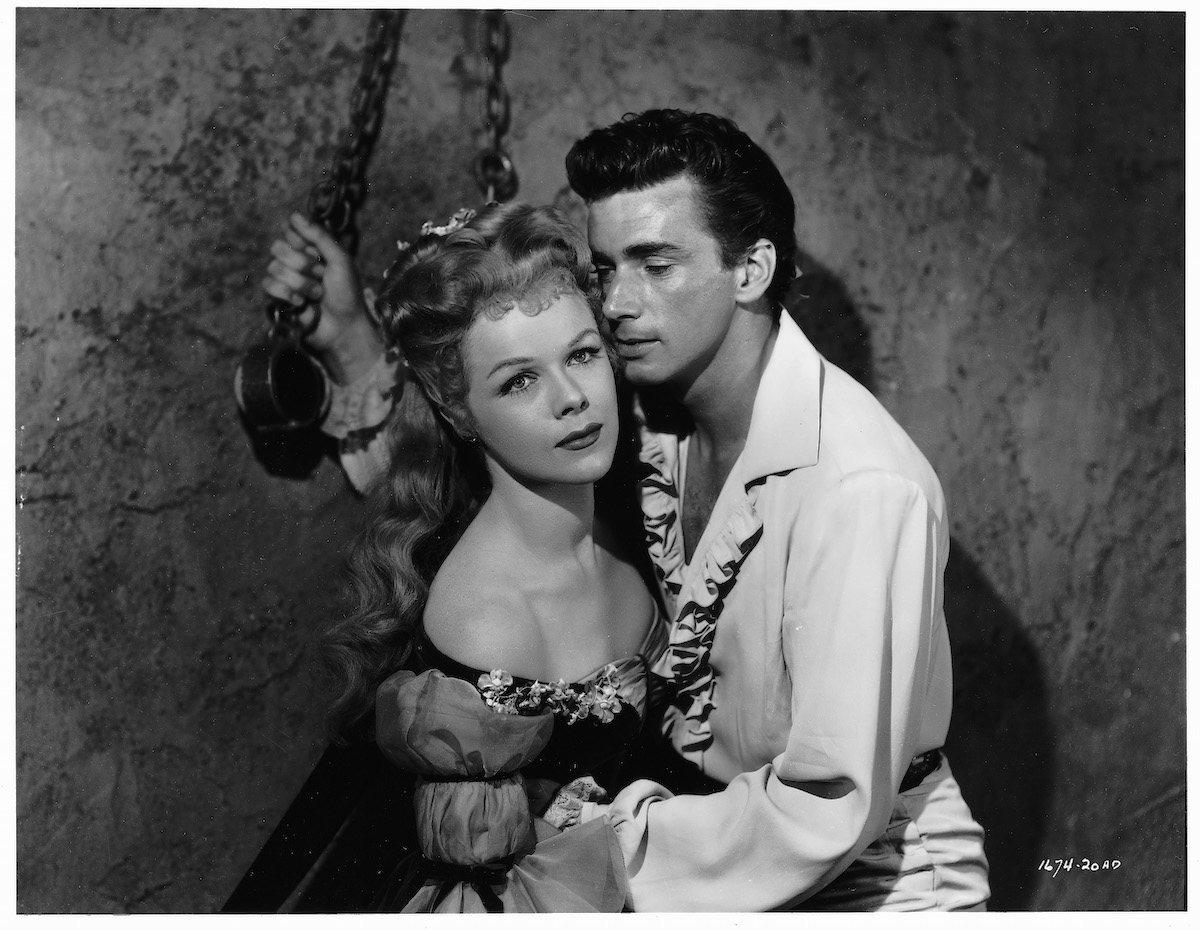

He’s now in the castle of Sire Alain de Maletroit (Laughton), whose dastardly plan involves imprisoning de Beaulieu and forcing him to wed Blanche, de Maletroit’s niece. She’s in love with another man, naturally, but he has mysteriously disappeared, and de Maletroit is determined to make her life miserable by marrying her to an unsuitable husband. Needless to add, though, his scheme starts to fall apart when de Beaulieu and Blanche fall for one another.

Meanwhile, it seems that other people—or things?—are held prisoner in the chateau too, and there are ominous comments about a medieval torturer once having worked there, which will eventually come to fruition in a clever if highly melodramatic and protracted climax.

Karloff’s role here is a supporting one, as the retainer Voltan, and it’s impossible to ever forget he’s Boris Karloff in a costume. Stapley is rather terrible, delivering his lines flatly in a thin, nasal voice; even his movements lack conviction. But Laughton is great value as always: clearly having fun in the role, by turns amused, threatening and chilling. His fake friendly smile and more genuine self-satisfied grin tell us much more about de Maletroit than any dialogue. Michael Pate as the simian servant Talon provides a sinister complement.

Laughton’s performance tends to give The Strange Door a giddily ludicrous air, but the film is also darker than it first seems, with its allusions to torture both physical and psychological (de Maletroit promises at one point that he will not inflict bodily harm, stressing the word) and—again exploiting the period’s fascination with psychology—hinting at issues related to his mother that de Maletroit does not want to face.

It is nicely shot at times, and just occasionally the period detail rings true: when de Maletroit is organising the wedding party, for example, sending out invitations and instructing the kitchen staff. But it’s very hit-and-miss, and insofar as The Strange Door is worth seeing at all, Laughton is the reason.

USA | 1951 | 81 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

directors: ‘The Invisible Ray’: Lambert Hillyer. ‘Black Friday’: Arthur Lubin. ‘The Strange Door’: Joseph Pevney.

writers: ‘The Invisible Ray’: John Colton, Howard Higgin & Douglas Hodges. ‘Black Friday’: Curt Siodmak & Eric Taylor. ‘The Strange Door’: Jerry Sackheim (based on The Sire de Maletroit’s Door by Robert Louis Stevenson).

starring: ‘The Invisible Ray’: Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Frances Drake & Frank Lawton. ‘Black Friday’: Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Stanley Ridges & Anne Nagel. ‘The Strange Door’: Charles Laughton, Boris Karloff, Sally Forrest & Richard Stapley.