VAMPYR (1932)

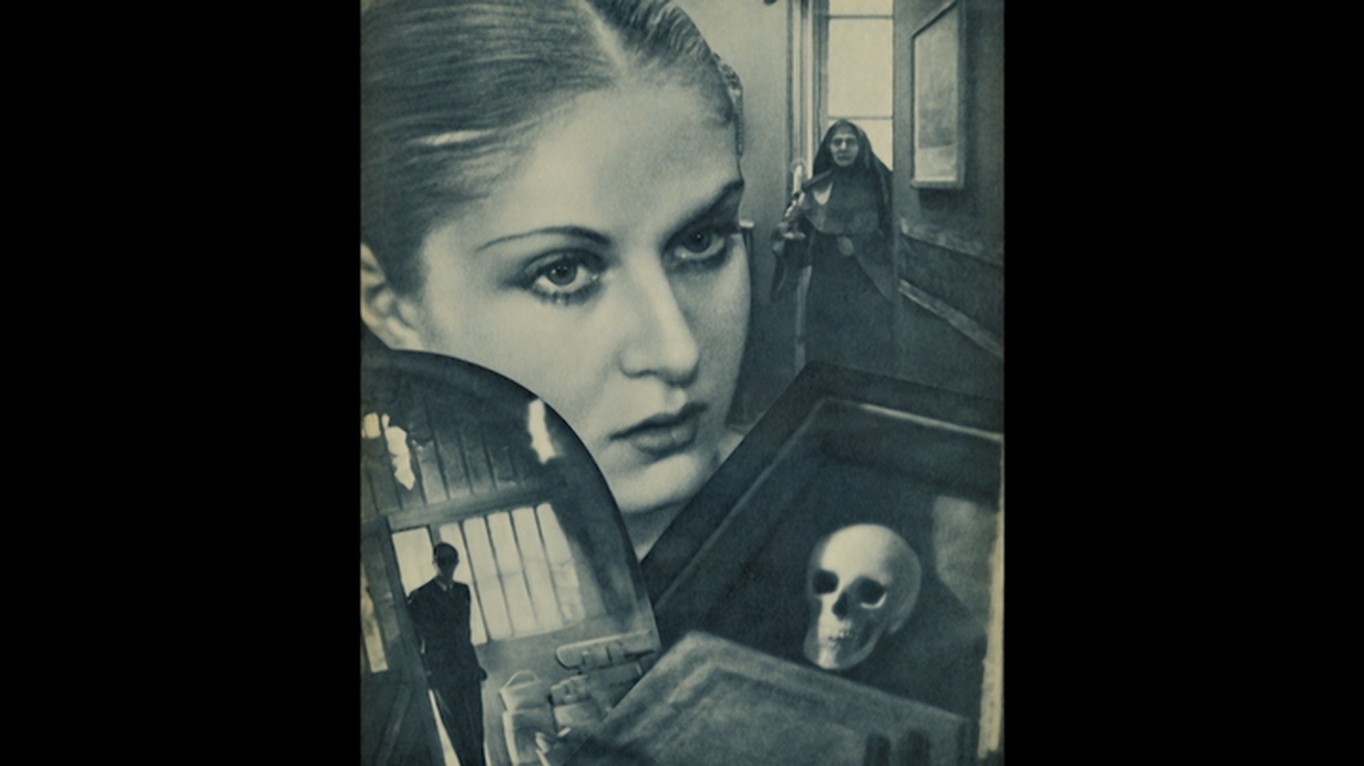

A drifter obsessed with the supernatural stumbles upon an inn where a severely ill adolescent girl is slowly becoming a vampire.

A drifter obsessed with the supernatural stumbles upon an inn where a severely ill adolescent girl is slowly becoming a vampire.

Vampyr is an unusual horror film in nearly every respect—from its troubled genesis, drawn-out production, delayed distribution, experimental cinematography, and its dreamlike narrative compiled from several vignettes of strangeness. It’s also an unusually beautiful horror film.

I first saw Vampyr in the mid-1980s when it was doing the rounds of art cinemas for its 50th anniversary. It was, and remains, a singular experience filled with truly haunting imagery: That old guy who comes into someone else’s room in the night and stares intently at them from the foot of their bed…. shadows that detach themselves from their corporeal owners and go off on their own murderous missions… the man who finds a coffin and then watches from the viewpoint of his own corpse as the lid is screwed shut, severe faces frowning down at him through a small viewing window. A film remembered as if one dreamt it.

Now, 90 years since its release, I’m grateful to Eureka Entertainment for a chance to revisit this sophisticated and seminal vampire movie. The latest in their ‘Masters of Cinema’ series, this sensitively restored Blu-ray represents a decade of international collaboration, bringing together material from several archives that have been scanned at 2K, then carefully graded and balanced by the Danish Film Institute.

Clearly, this was a huge challenge, as the film has never been seamless, revelling in its disconcertingly disjointed narrative structure and the varying textures of intentionally distressed film stock. Even when it was new, the film would’ve looked old, or perhaps ‘timeless’. Some of the scenes are so pale and indistinct that they recall the photographs supposedly produced by Victorian mediums by thought transference alone—ghostly and ethereal. Other shots are so dark that features are barely discerned, with shadows and solidity merging.

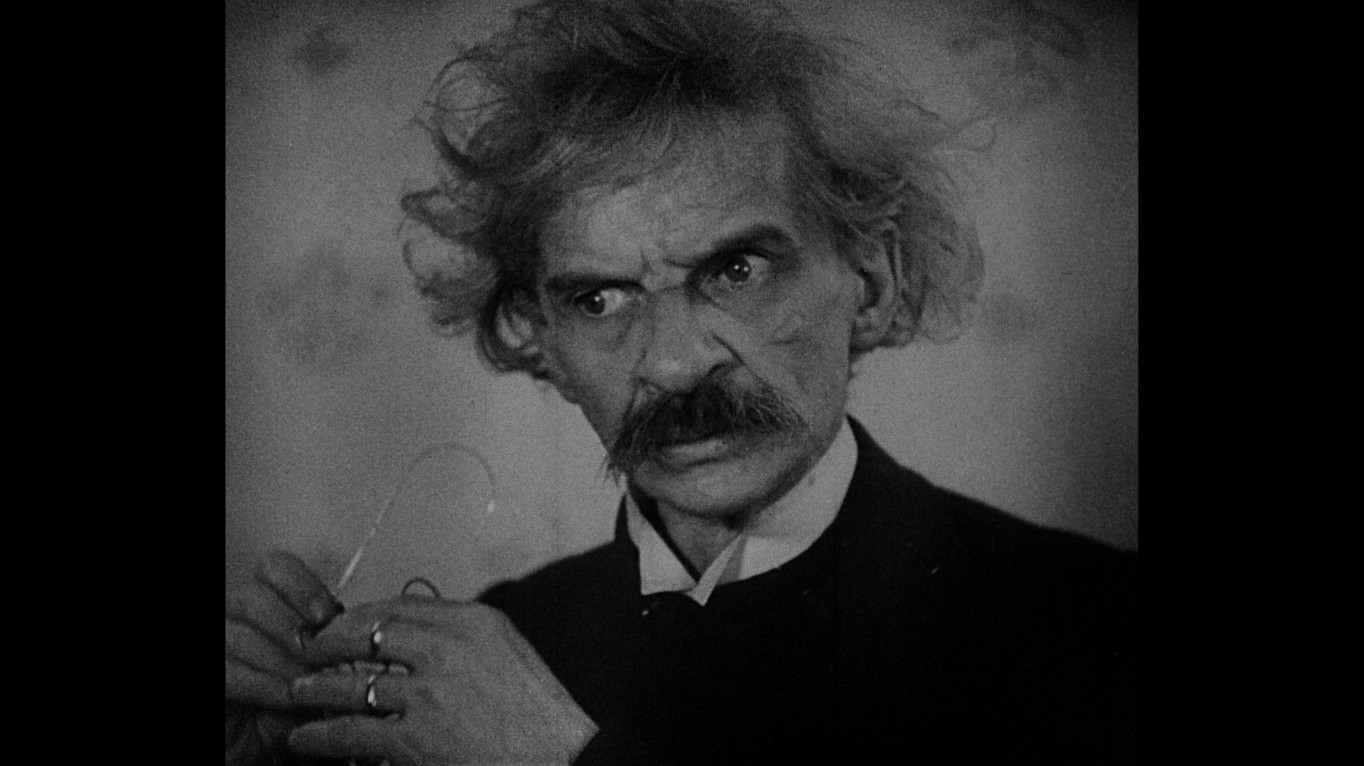

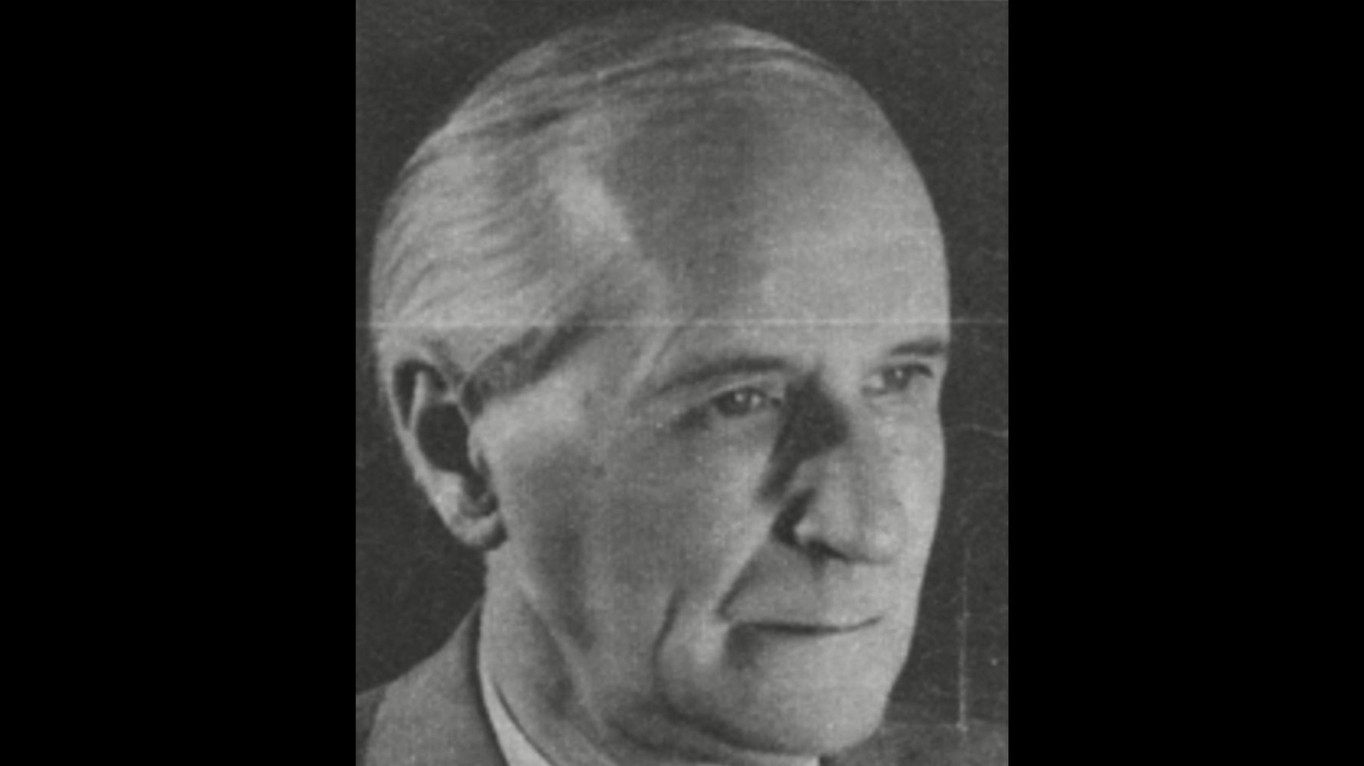

Director Carl Theodor Dreyer is now recognised as a giant of early cinema with his silent classic The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), generally cited as his masterpiece. It had been critically well-received on its release, a review in the New York Times hailing it as the greatest art film yet, and the National Board of Review ranked it amongst the top five foreign films in its inaugural awards of 1929.

The public didn’t agree, alas, and The Passion of Joan of Arc was a spectacular box office failure due to, or despite, the controversy it stirred up. It was banned, outright, in the UK and the Catholic Church demanded it be censored, to which the French government agreed. Société Générale des Films, its distributor, recut the film and Dreyer sued for breach of contract. The director found himself tied up in a lawsuit that dragged on for three years, making it impossible for him to embark on any further projects within the film industry. So, he looked elsewhere.

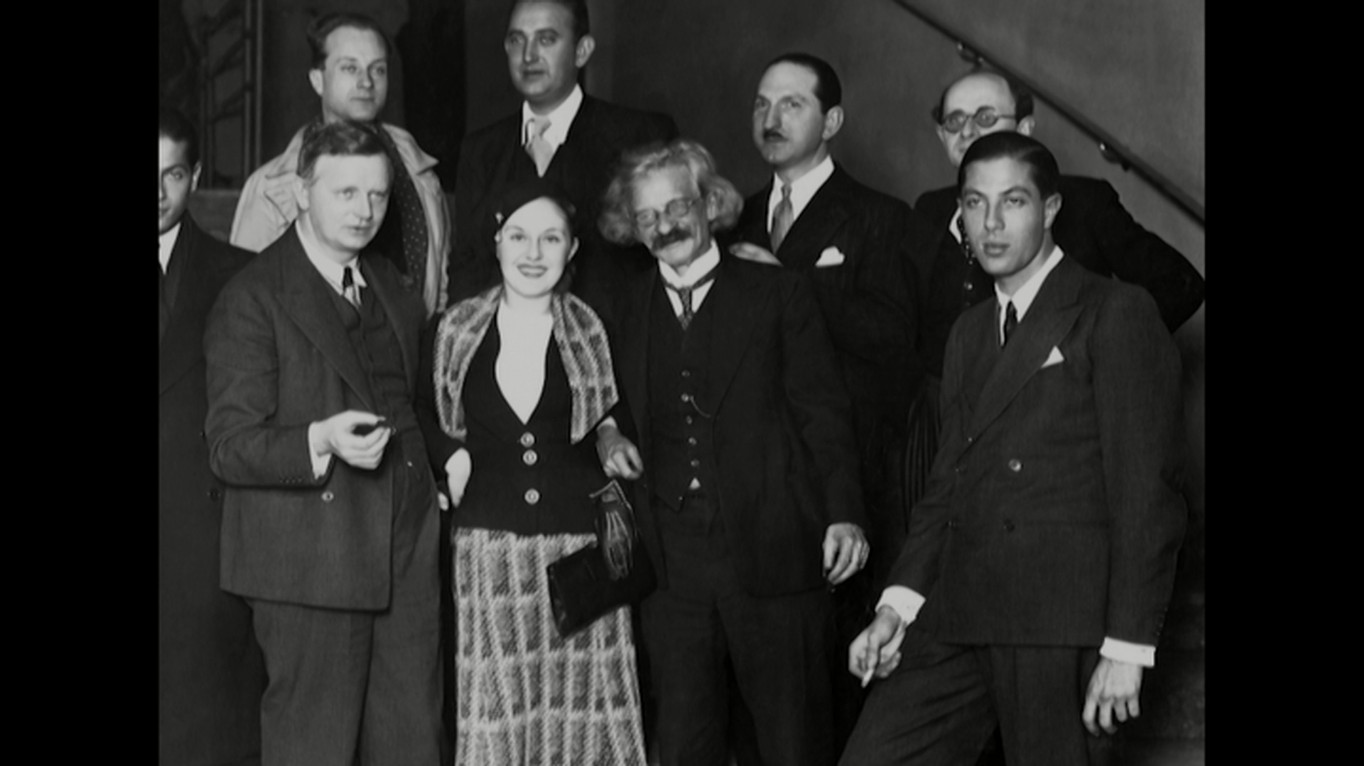

Around this time, Dreyer met the Baron Nicolas Louis Alexandre de Gunzburg, a descendent of Russian nobility, who’d been born in Paris where he lived as an exile after the Bolshevik revolution of 1917. He was well-known in Parisian society for his lavish parties hosted in huge, purpose-built environments designed by artists, sculptors, and theatrical set makers. In Russia, his family had been generous patrons of the arts and the young Baron, wanting to continue the tradition, agreed to finance Dreyer’s next film, provided he was given the male lead. Dreyer readily agreed, seeing a way to make a film entirely outside the constraints of the studio system and, by the end of 1929, Dreyer had started planning and writing what would become Vampyr.

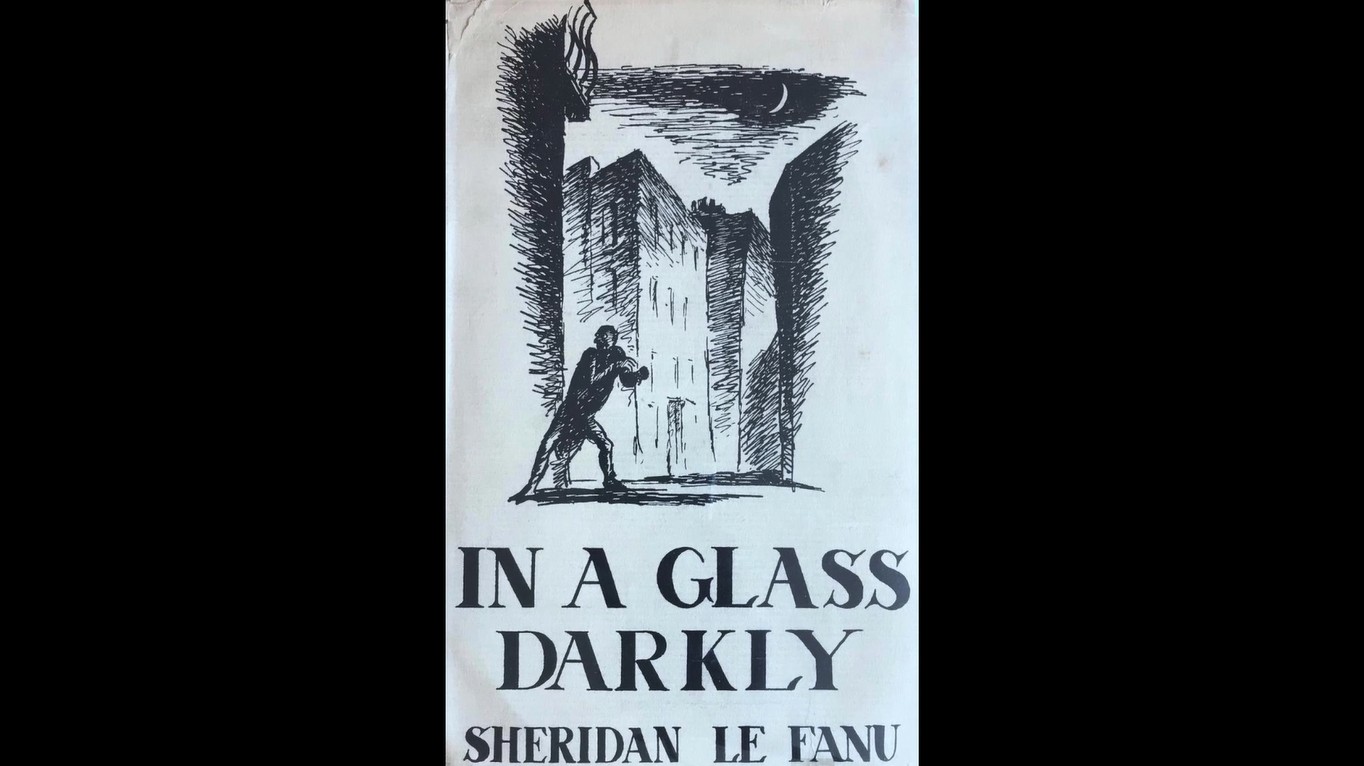

They’d found a common interest in the literature of the supernatural and Dryer began his research for their film by reading 30 or more mystery novels and tales of the imagination to analyse how they worked, noting common motifs he thought would be effective on screen. He also revisited his grandmother’s extensive collection of occult books that numbered in the hundreds. Finally, he focussed on the 1872 collection of Gothic short stories, In a Glass Darkly, by Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu, which has since become the source material for many subsequent horror films, particularly the lesbian vampire story Carmilla, which has spawned at least a dozen cinematic interpretations.

Instead of adapting just one of the stories in the collection, Dreyer’s script attempts to encapsulate the milieu of the whole book, expressing his personal response and lingering impressions left by all five stories whilst creating a new one. The two stories which contributed recognisable elements to Vampyr were Carmilla, featuring a female vampire preying upon young women, and The Room in the Dragon Volant, which has no overt supernatural elements but does include a sequence involving a paralyzed victim witnessing their own internment from within the coffin. The character that links the stories is Doctor Hesselius, an occult detective, whose character is just about discernible in Vampyr’s protagonist, Allan Gray, who stumbles upon a mystery he is then instrumental in solving.

We meet Allan Gray (Julian West, stage name of the Baron de Gunzburg) as he disembarks from a small river barge and, although this is a sound film, a lengthy caption tells us he’s immersed in studies of devil worship and vampires and his obsession with the superstitions of the past has made him this dreamer and aimless wanderer who comes to a secluded inn on the outskirts of Courtempierre. He’s travelling light with minimum luggage and carries a long-handled net which takes on symbolic meanings of entrapment as the plot develops. Later, as he becomes caught up in supernatural intrigue, he will pass the enlarged shadow of his net, seemingly big enough to capture him.

He finds the inn locked up and we see his face framed through the window of the door, another recurring motif with shifting interpretations throughout the film. Doors can be open or locked and, in some ways, resemble coffin lids. A closed window is an invisible barrier that may be looked through, but not passed through, like the intangible transition between life and death. In case this symbolism’s too subtle, a man carrying a reaper-style scythe tolls the riverside bell to summon the ferryman. Only then, is Gray granted access to the inn and shown to his room.

That night, his sleep is interrupted by an eerie predawn light that pervades his room as the key in the lock slowly turns itself and a stranger enters. The man shuffles to the foot of the bed and stares intently at Gray in discomforting silence until he blurts, “She must not die, you understand?” He then produces a package and writes something upon it before leaving, the key turning of its own accord, locking the door after him. Who must not die? And what’s more, who was that man? Gray investigates the small package left on the cabinet, it is wrapped in paper and bears two wax seals. The man had written, “to be opened upon my death.” How’s that for an enigmatic opening gambit?

Already, Dreyer has suggested two possible readings of the narrative. Has Gray lost the ability to differentiate between dream and reality? After all, the original German title—Vampyr, Der Traum des Allan Gray—translates as Vampyr, The Dream of Allan Gray. Or is he already in some hinterland between life and death, having been brought to this strange shore by a spectral ferryman across the river of death, perhaps to retrieve a soul from purgatory? There are many mythic connotations to be enjoyed and there’s also a sound grounding in folklore.

The location, Courtempierre, is a real French town in the central Loire region. Local folktales tell of ghostly bargemen that ferry one across the River Loire to an opposite bank that is no longer of this world. Such folktales may have several different origins. There’s the obvious link to the ferryman of Greek myth and Chris de Burgh songs. Also, smugglers who used the river to bring in their contraband may have been seen in the night, mistaken for ghostly ferrymen but never seen again in the same spot. Perhaps unscrupulous ones would offer a crossing only to do away with the hapless witness and dump the body overboard. In a way, their victims would be crossing the river into another world: the afterlife.

There’s one well-known folktale, retold and adapted in different regions, but the version linked with the Loire valley tells of the devil appearing to a town elder and offering to solve the problem of these frightening ferrymen by building a bridge to make them redundant. The price he asks is merely a single soul, of the first to cross the bridge in the morning when it is completed. The elder agrees but outwits the devil by allowing a cat to cross the bridge ahead of him at dawn. The devil gets the soul of a cat, and the town gets a safer river crossing. The tale usually concludes that the devil was ‘rolled in flour’, a common French idiom which means to be cleverly deceived or made a fool of. (No, not that very rude English-language version.) It’s believed to stem from the old tradition of medieval clowns using flour to whiten their faces—think of a classic French mime artist. In the poetic justice meted at the film’s finale, the ‘devil’ isn’t merely rolled in flour, but suffocated in it during a suitably improbable but gruesome sequence involving supernatural vengeance from ‘the other side’.

It seems that Dreyer conducted thorough research into the legends and more obscure lore of the Loire. Which, long before the internet, would’ve been quite a task. He probably made use of that extensive library of occult books collected by his grandmother, and one assumes he was regaled by such spooky stories in his childhood, too. Although Vampyr has all the visual trappings of Gothic horror—candlelight, cemeteries, and crumbling architecture—it really feels like a fairy tale and falls just as much into the folk horror tradition.

Production lasted more than a year and everything was shot on location in and around Courtempierre, with the cast and crew staying at the ivy-clad Château de Courtempierre, which is also the manor house in the movie. The exterior shots were filmed only during the first few hours of daylight when natural mists rose off the river, lakes, and marshlands, catching the low dawn sunlight that would pass as the twilight of dusk. Other nearby locations were used and Dreyer adapted his script to make better use of the opportunities they presented. For example, one of the vampires was to die by drowning in the mire, but a local flour mill, with its white dusty interiors and menacing mechanisms suggested an entirely different and memorable conclusion. Likewise, a large derelict factory found on the outskirts of Paris offered plenty of potential with its multi-levelled interior and large blank walls, many of which Dreyer had whitewashed so projected shadows would become even more dramatic.

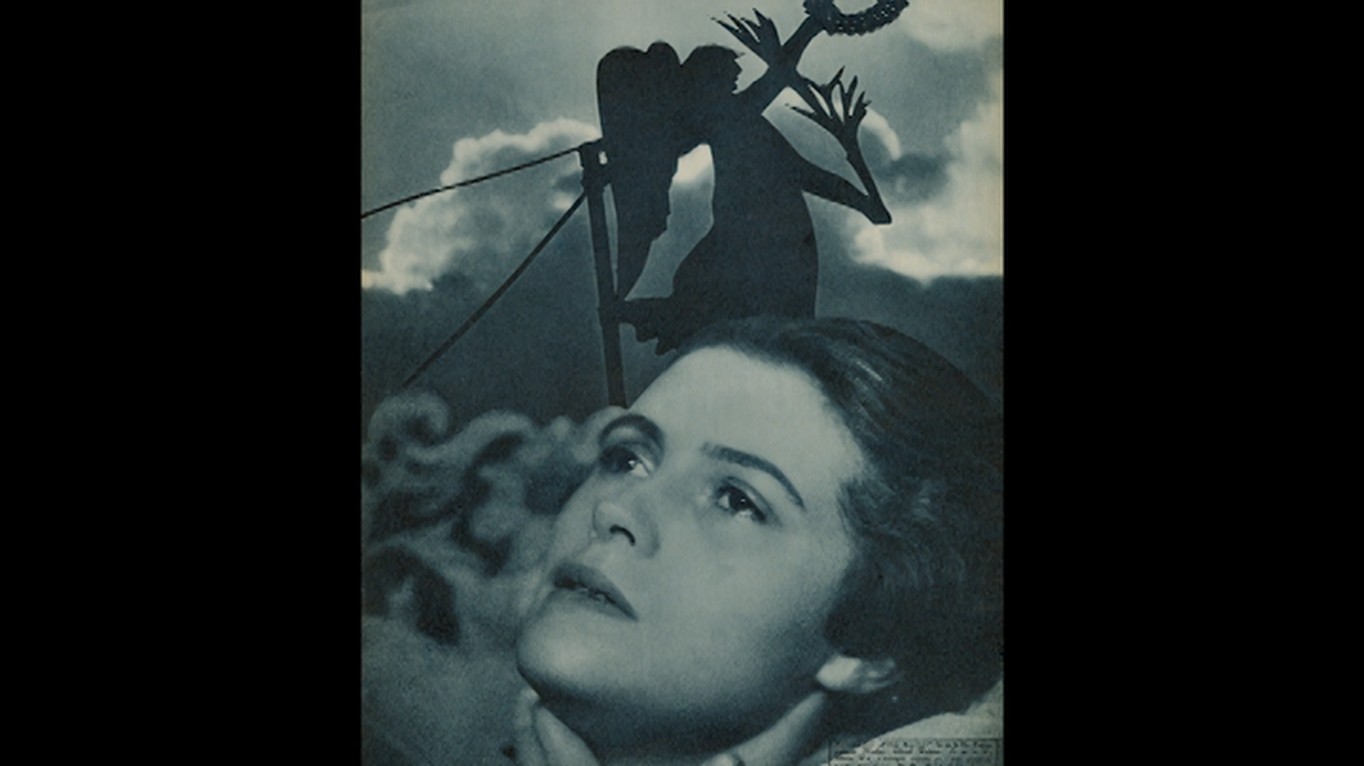

The visual theme of whiteness to counterbalance shadows may have been suggested by the flour of the mill and the folkloric phrase linked to the Devil, but also by a mistake during the early days of principal photography when some of the rushes were spoilt. The grainy, ghostly images that remained on the reel were strangely beautiful and Dreyer asked his cinematographer Rudolph Maté, who had also shot The Passion of Joan of Arc, how they could be achieved intentionally. Different techniques were tested including ‘flashing the film’, which involves a controlled exposure to dim light before loading the camera. Some scenes were filmed through layers of gauzes that were lit from the side to create the illusion of a luminous mist.

What seems like a visual quirk, one that lends the entire film its distinctively dreamy appeal, is one of the elements from the source material that Dreyer faithfully renders. A line from chapter two of Carmilla describes “over the sward and low grounds a thin film of mist was stealing like smoke, marking the distances with a transparent veil; and here and there we could see the river faintly flashing in the moonlight.”

Dreyer was interested in the concrete realism of actual locations being dissolved by inventive photography and broken down into disjointed space by clever editing. An actor may leave one room and enter another in a totally different place. An interior doorway may lead them onto a meadow or churchyard. He intentionally applies the logic of dreams to break down reality whilst exploring cinema’s parallel power to do the same. This places Vampyr in the arena of surrealist film, just as much as horror.

His use of non-actors helps achieve this sense of delirium. The Baron was a banker at the time with no professional acting experience and Dreyer selected others by their appearance or their willingness and availability. This necessitated a particular style of direction to restrain their movements and use their ‘blankness’. For the most part, they become surreal mannequins, statically posed as if in frames from a graphic novel, their motivations and dianoia revealed through sympathetic environments and narrative editing. They tend to move slowly, deliberately, as if in a dream, and their stilted, mistimed dialogue only adds to this. Something that would be noted by David Lynch and similarly utilised in Eraserhead (1977), and Lynch isn’t the only director to evoke Vampyr in their own work. The influence is palpable throughout Giorgio Ferroni’s Mill of the Stone Women (1960), which pretty much recycles the opening scenes, and there is plenty of overlap in Rainer Sarnet’s folk horror masterpiece, November (2017). Guillermo del Toro (Crimson Peak) cites it as a major influence and inspiration, which is why he provides one of the two excellent audio commentaries found on this Blu-ray release.

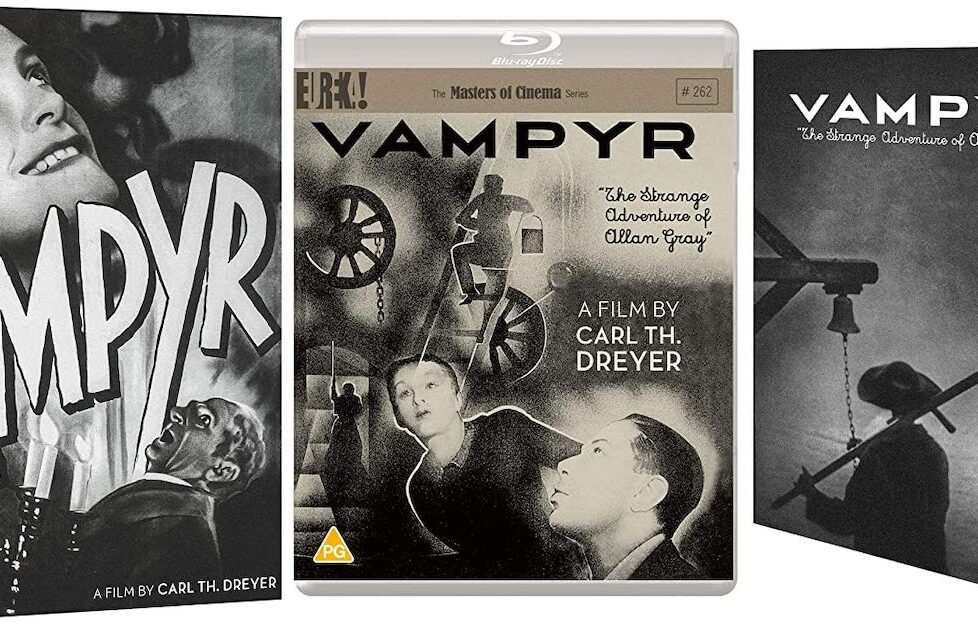

The sinister village doctor is played by Jan Hieronimko, reputedly a man spotted on a train, who does a great job as the evil vampire henchman channelling a nice set of contemporary stereotypes, remixing them into his own distinctive composite that ends up looking like a manic Mark Twain. He has the crazy intense stare and wild hair of Rotwang in Metropolis (1927), Dr Caligari’s round-rimmed spectacles and gestural tension, and the scary moustache of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Rena Mandel was a professional artist’s model, so she knew how to interact with natural light and shade and is perfect as the fragile Gisèle, the film’s damsel in distress that Gray must attempt to save from the relentlessly encroaching evil. She’s in peril from all angles and destined to become the vampire’s next victim should her sister, Léone (Sybille Schmitz) succumb to the curse.

Their father is the lord of the manor (Maurice Schutz, one of the films two professional actors) and we recognise him as the spectral stranger who visited Gray’s room at the inn. So, we may deduce that Léone, or perhaps Gisèle, is the one who “must not die.” The first act closes with his own death, seemingly murdered by an errant shadow.

This prompts Gray to open the mysterious package to find it contains a book, The Strange History of Vampires, which now replaces any captions with lingering shots of its pages as it is consulted by candlelight. The book has a chapter on the local vampire lore of Courtempierre and becomes Gray’s manual for confronting the pervasive evil. Apparently, Dreyer spent two whole days personally shooting the closeups of the pages and maintained that the meticulously constructed prop was also an actor giving a vital performance. It was so convincing that many vampire scholars took it to be the real deal and fruitlessly searched for a copy.

Sybille Schmitz was the second professional cast member and it shows. Here, she’s basically fulfilling the same role as Lucy in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, fading away from some unknown malady as she falls deeper under the vampire’s thrall. The part calls upon her to transition from virginal purity, through religious passion akin to that of Dreyer’s Joan of Arc, to demonically malevolent. All in the space of a single shot.

The sequence in which she’s lured out of her room at night into the grounds of the manor is closely echoed in Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula (1992) when the Count psychically draws Lucy to him and is caught in bloodsucking creature mode before uttering the line, “no, don’t see me,” and vanishing. The scene in Vampyr is perhaps less eroticised, though still clearly has such connotations. The position of Léone’s body intentionally mimics the recognisable pose of the woman in the famous Henry Fusili painting, ‘The Nightmare’, which was often reproduced and is now recognised as a keystone of the romantic Gothic visual identity. Here though, the young vulnerable woman is vampirised not by a demonic incubus or masculine assailant but by a frail woman, the deceased aristocrat, Marguerite Chopin (Henriette Gérard).

Vampyr marks the introduction of the vampire as crone to the cinematic canon. Sure, there are a few prior examples of female vampires—The Vampire (1913) starring Alice Hollister may be the earliest—but already the female vampire is established as a young, beautiful seductress, templating ‘the vamp’. The character of Carmilla in the original tale is ancient yet appears young, frail and beautiful. Chopin is more closely associated with the witch archetype which again lends Vampyr its more fairy-tale feel.

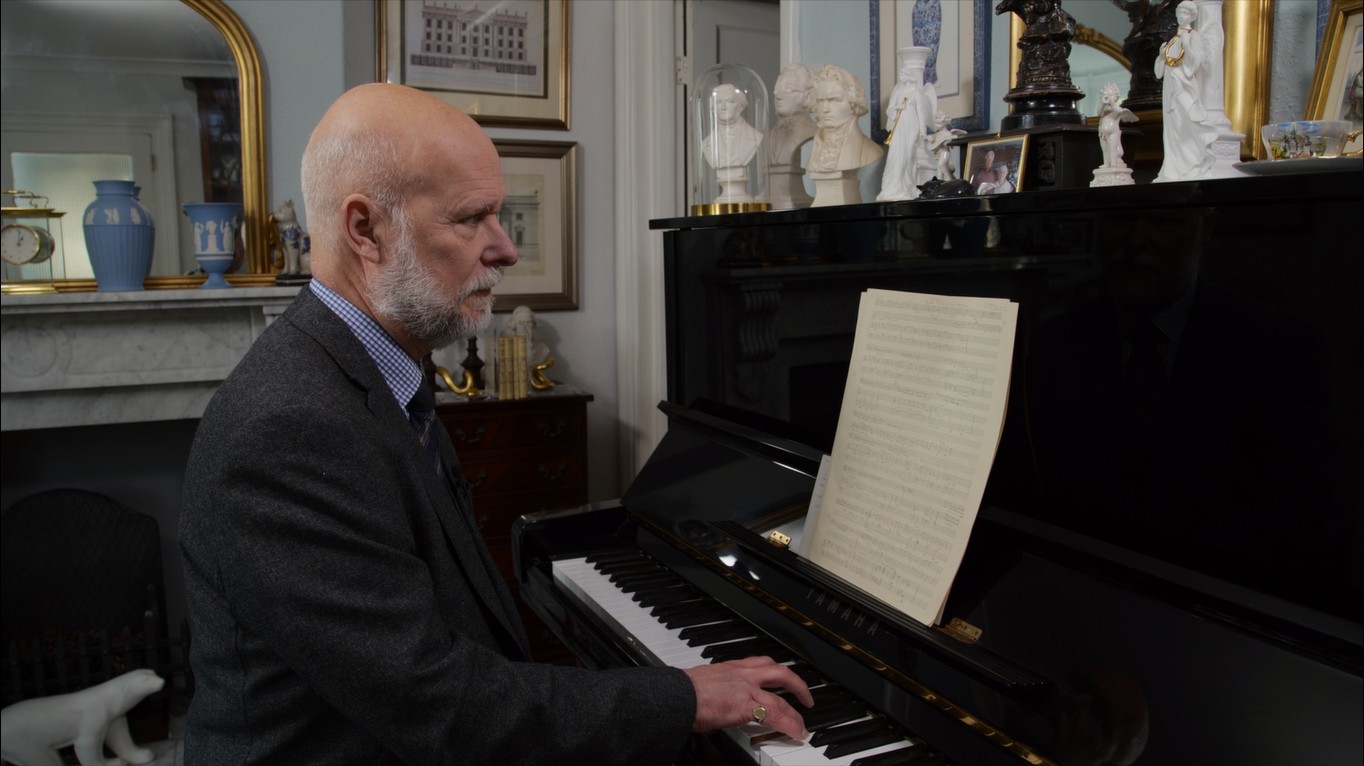

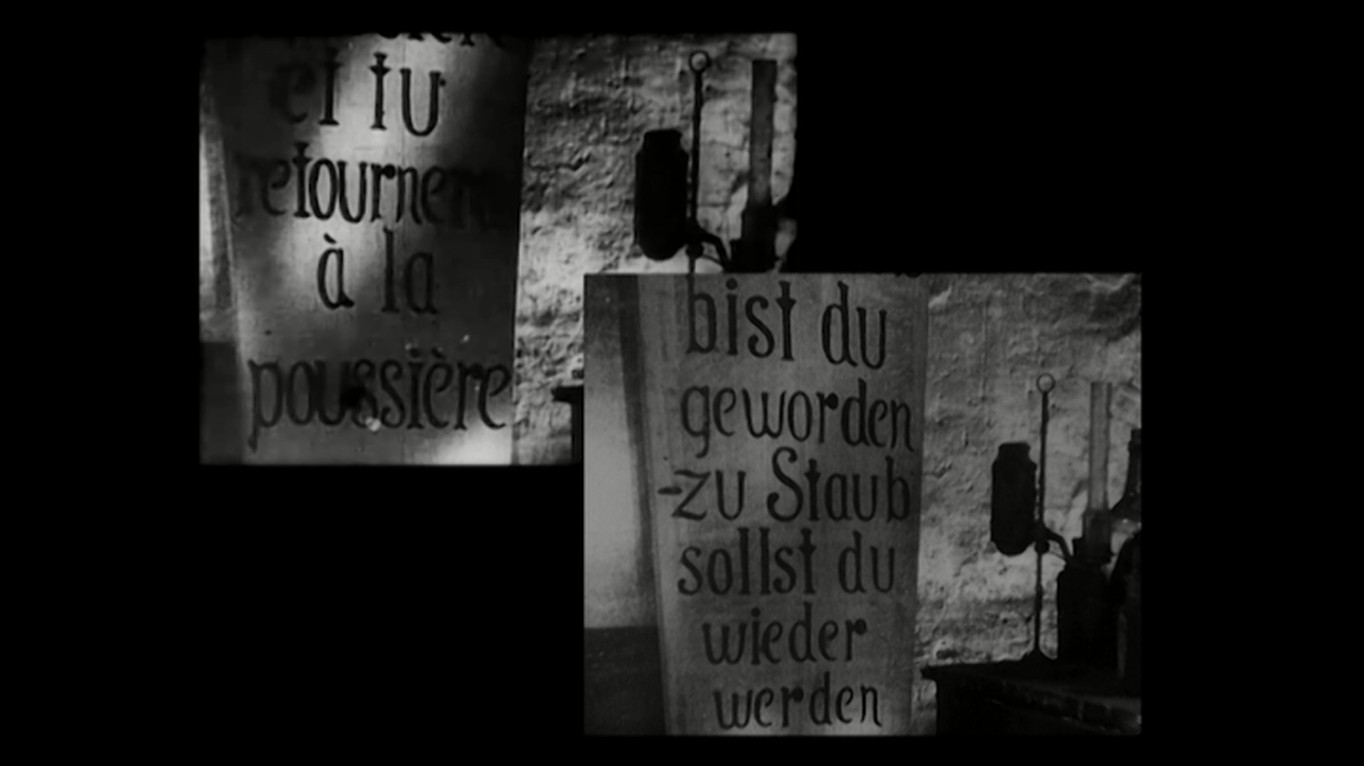

Vampyr was also Dreyer’s first sound film, though he approached it as a silent and employed the same visual grammar, sometimes it feels like a visually degraded extension of his earlier film with Gothic undertones, Michael (1924). That’s not to say he neglected the sound aspects. He shot each dialogue scene in three separate takes, to which the actors were intended to later add French, German, and English translations that matched with their mouth movements. He also uses sound to add an extra dimension beyond the boundaries of the frame. There are inexplicable, non-diegetic noises, muffled mutterings from other rooms, animal calls, all subtly unobtrusive, yet adding to the general unease. He also makes brilliant use of the original score by Wolfgang Zeller which plays a huge part in evoking an immersive atmosphere with its melancholic beauty.

After a long production, involving cleverly manipulated shadows and experimental processes such as stop-frame animation, mechanical in-camera effects, double exposure, and reversed footage, Dreyer obsessively edited and re-edited the results. He fluently combines the language of cinema and dream, constructing an unreal world from real-world locations. Some threads he jettisoned entirely, including a complex sequence involving a shepherd being chased by a pack of dogs under remote vampiric control. Though there remains a reference to the sound of hounds when Gray first meets the doctor, the noises being partly explained by the presence of a parrot, implying the bird mimics the baying of dogs and crying of children. However, Dreyer’s elective cuts were not the only ones to be made…

Vampyr was completed ahead of Tod Browning’s iconic Dracula (1931), and James Whale’s famous Frankenstein (1931), but the European distributors decided to delay its release until after these two films had increased audience acceptance of the horror trend. The plan backfired as Dreyer’s masterpiece has little common ground with its Hollywood contemporaries that trained cinemagoers to expect something quite specific from the genre that the more ponderous and engrossing Vampyr refused to deliver.

The first screenings were poorly received, to say the least. The Berlin premiere in May 1932 was booed and many walked out! Another screening ended in a riot when the audience, en masse, demanded their tickets refunded and the police had to intervene to disperse the disgruntled punters. The German censors ordered two key scenes to be significantly cut. The pinioning of the vampire to the earth with a long iron spike was deemed too shockingly explicit, and the asphyxiation by flour in the mill too prolonged and gruesome. These cuts necessitated further cuts that Dreyer elected to make to maintain narrative integrity. The planned Danish and English-language versions were aborted and, shortly after release, the distributors lost interest. Vampyr faded into obscurity like a vampire in the light of day. Dreyer suffered a nervous breakdown, and it would be more than a decade before he recovered enough credibility to make another film, Day of Wrath (1943) set in 17th-century Denmark and sharing some themes of witchcraft. Of Dreyer’s more than 20 films, he’s best remembered for Vampyr. It was such a weird and wonderful creation that it refused to die and although not prominent enough to make a major impact on the early development of horror, its influence has gradually emerged and it can now be considered among the few truly seminal contributions to the genre.

GERMANY • FRANCE | 1932 | 74 MINUTES | 1.19:1 | BLACK & WHITE | GERMAN

director: Carl Theodor Dreyer.

writers: Carl Theodor Dreyer & Christen Jul.

starring: Julian West, Maurice Shutz, Sybille Schmitz, Rena Mandel, Jan Hieronimko.