MICHAEL (1924)

Triangle story: painter, his young male model, unscrupulous princess.

Triangle story: painter, his young male model, unscrupulous princess.

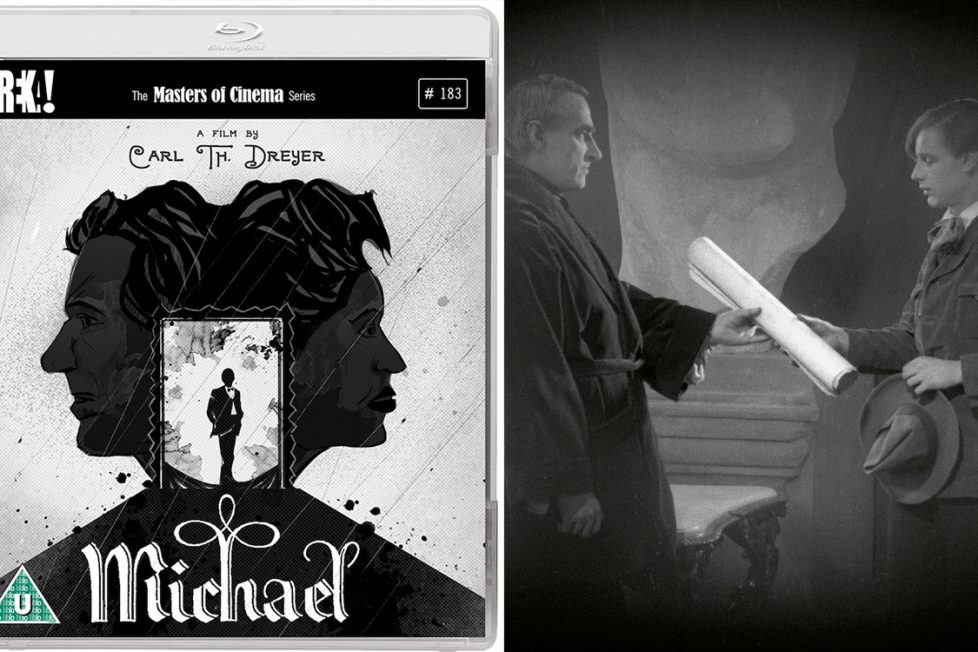

An aspiring young artist, Michael (Walter Slezak), shows some of his sketches to renowned painter Claude Zoret (Benjamin Christensen) who, in no uncertain terms, lets him know they aren’t very good. As the young man dejectedly turns to leave, Zoret asks him if he’d be interested in becoming his model. It seems the older, established artist is quite taken with the young man’s good looks, and Michael perhaps hopes to earn a little whilst he learns from the master he clearly admires. But is all as innocent as it appears?

The rest of the film is preoccupied with this question. Does Zoret really want to do more than just paint Michael? Is there a mutual respect, or a more basic attraction between the two men? Why does Zoret’s dear old friend, Charles Switt (Robert Garrison), seem to resent the younger man’s presence, and why does the later affair between Michael and Princess Lucia Zamikoff (Nora Gregor) seem to upset what on the surface appeared to be a father-son sort of friendship? As it turns out, there are more questions than answers to be found here. The plot has been described as a love-triangle, but it’s more of a love-polygon, exploring relationships between teacher, pupil, artist, muse, parents, offspring, friendship, resentment, love, and betrayal…

Some critics have hailed Michael as one of the earliest contributions to gay cinema. The central focus of the film certainly is the relationship between the three male leads: the artist Zoret, his muse Michael, and his friend Switt. But having paid close attention, I can’t say that it’s addressing homosexuality head-on. Admittedly, it would’ve been problematic to do so in any explicit way during the 1920s. To me, it seems to be dealing with the nature of yearning and how we maybe make do with substitutes, rather than spoil those yearnings by fulfilling them.

Several times, Michael is referred to as being like a son to Zoret. The artist makes remarks that equate his artistic output with offspring—the children he never had. It’s obvious that he appreciates the aesthetic beauty of Michael as a model and muse, but this ‘love’ remains chaste. He also talks of his old friend Switt, the critic and journalist, in terms of great affection, and it’s their friendship that endures to the end.

More overtly, it seems to be the passing of his own youth and impending mortality that drives Zoret to capture Michael in his prime, through art. Also, when Michael finds he can get by on his looks alone, the youth relinquishes his own artistic aspirations and becomes quite materialistic. Interestingly, it’s not Zoret’s portraits of youth and beauty, but a grand painting of a wizened old man “who has lost everything” that eventually wins Zoret the applause and accolades of society. He is toasted as “the painter of suffering…”

Dreyer was, perhaps, exploring the ever-present problem for any artist using visual media: how does one express anything beyond the surface, when all you have to work with is ultimately another surface? Here he aligns the new expressive mode of cinema with the long-established tradition of painting. So, it’s fitting that his main character is a painter of a very traditional style. How does an artist capture anything profound when all they can record is the appearance of a model, or actor, and then represent it on canvas, or screen?

The whole production feels more like a stage play recorded on film, but with the lighting and dark vignette frames lending a more painterly feel. Most of the action takes place in the interior sets of Zoret’s studio or his rooms, making it feel staged. Dreyer has yet to develop the mastery of the medium seen in his acclaimed breakthrough The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), and particularly in his most distinctive work, the visually inventive and truly haunting Vampyr (1932).

When viewed in context with what Sergei Eisenstein had just done with Glumov’s Diary (1923) and was achieving with Strike (1925), Michael was not adventurous at all. The most striking innovation with Michael is the effective use of the close-up in lieu of dialogue. Not that this is by any means the first use of close-ups, but here Dreyer lingers on the faces of the actors as they express a complex parade of emotions—a mobility not at all available to the easel painter and something that didn’t exist in the vocabulary of theatre. It allows the more able of the cast to go beyond the melodramatic style and introduce a touch more subtlety. People sometimes think one thing, yet say another. It reminded me of the way Andrei Tarkovsky often lingers on the silent, yet profoundly expressive faces of his cast, allowing the viewer time to connect with their often ambiguous inner turmoil…

Ambiguity. That seems to be at the core of Michael. Dreyer has chosen to express things poetically, rather than pragmatically, allowing each of us to connect with whatever seems most personally relevant. A technique more often exemplified in the lyrics of poignant songs. (So, that’s why the songs of Momus were running through my head whilst watching!)

The screenplay was adapted from Herman Bang’s 1902 novel by the hugely influential Thea Von Harbou, who also wrote Metropolis (1927) and later married Fritz Lang. Apparently, the original novel is also very ambiguous and seems focussed more on friendship and betrayal, rather than gender identity. Bang is known to have been homosexual, so this slants any readings, but he may well have been going for something much more universal about the nature of platonic love along with the torment of unrequited desire. The film remains open to interpretation and, just like the fluidic nature of gender identity, does not allow itself to be simply polarised.

One appealing aspects of this, and indeed most films from the silent age, is the visual qualities, not least the stylised face make-up. Actors powdered their faces into a flat white, with eyes, lips and other features emphasised with outlines of dark kohl. This was partly a hang-over from the theatre, where features would need to be highly visible in the relatively dim lighting. Back then, all professional actors were theatre-trained and film hadn’t been round long enough for them to adapt to it as a new medium.

Sufficient lighting was hard to come by. In a studio, artificial light wasn’t quite enough, and outdoors the direct sunlight was too much. So the actors fell-back on their stage make-up techniques, with minor adjustments. The reactive chemicals of early celluloid were blue-sensitive and warmer colours came out darker. Reds came out black, for example. So, healthy, rosy cheeks would appear dirty grey. Also features could be easily lost, either to lack of shadow, or too much contrast. The solution was to re-draw the actors’ faces in a way that was more camera-friendly. After all, in a silent movie, it’s very important to be able to read expressions, and there are plenty of expressions to be read in Michael. The entire cast give a tour de force of face acting. I think nearly every character gets a turn to do some crying, and lots of looking wistfully off-screen.

The mise en scène had to be just as carefully considered in terms of colour and contrasts. The sets and costumes were in the hands of Hugo Häring. His background as a stage designer for the theatre, specialising in grand opera productions, is palpable throughout. The sets and costumes are reasonably realistic, but many of the props are at a more theatrical scale—the huge crucifixes, Greek-style statuary and a colossal head. Michael was his sole venture into the world of filmmaking.

By the 1920s, not many actors would have had long film careers, but Benjamin Christensen had already proved himself to be more than an expressive actor, having written and directed the ‘documentary’ about witchcraft through the ages, Häxan (1922), which was a far more visually remarkable film and for which he is better remembered. And deservedly so.

Dreyer and Christensen are among the most important directors to come out of Denmark. So, to have both involved on this single project is remarkable. The country didn’t really produce any of similar stature until Lars von Trier came to prominence in the 1980s. Interestingly, Trier would direct the TV movie Medea (1988), using Dreyer’s unrealised screenplay of the classical Greek play.

Of the cast, Walter Slezak was the only one to demonstrate any real career longevity after Michael. Unlike many silent actors, he adapted to the new talkies. He left Germany in the 1930s and successfully transitioned to more international productions like Jean Renoir’s This Land is Mine (1943) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944). He starred alongside Douglas Fairbanks Jr in Sinbad the Sailor (1947), and with Ronald Raegan in Bedtime for Bonzo (1951), establishing himself as a character actor and enjoying a prolific career. His final performance was in a two-part 1980 episode of TV’s The Love Boat.

Michael is a tragedy full of emotional theatrics, exploring the intersections of love, the creative spirit, melancholia, and human frailty. On the whole, it’s not a very uplifting experience and has to be approached in the context of its time. By today’s standards, it’s no great shakes, but for the time it was made, it was a solid achievement. I still can’t help thinking that there must have been sources out there with more potential than Bang’s novel to express similar sentiments. The works of Oscar Wilde spring to mind, particularly The Picture of Dorian Gray, which, coincidentally, had first been adapted for the screen by another Danish director, Axel Strøm, in 1910.

Michael will mainly appeal to those interested in early cinema as an emergent art form, aficionados of Danish cinema, and fans of Dreyer interested in understanding the development of his work. I’m guessing that if you’ve read this far, then you may be in that demographic! If so, you can’t go wrong with this impressive high definition 2K restoration from Eureka Video. There’s no way it could be made any clearer or have a better range of grey tones. It’s hard to believe a print from that era could retain so much for the restorers to bring out.

The 2006 score by Pierre Oser, presented in uncompressed clarity, sounds authentic and is suitably disconsolate and moody. There’s also a full-length audio commentary by Casper Tybjerg, Associate Professor in the Department of Media, Cognition and Communication at the University of Copenhagen and a scholar of the life and works of Dreyer—so I guess he’s pretty qualified for the gig, and will not disappoint those with a genuine interest in getting ‘under the surface’ of the film.

The accompanying collectors’ booklet is also a lovely little thing showcasing some archival imagery and promotional material. At 56 pages, it’s not just a token insert, either. It includes a translation of the text from the original Danish cinema programme and gathers some archival essays about the film: Tom Milne’s The World Inside Me from 1971; a tribute by Jean Renoir, Dreyer’s Sin, written in 1968; a reprint of Nick Wrigley’s essay from the film’s 80th anniversary DVD release; and a brand new essay by film historian Philip Kemp.

There is also a fascinating video essay included as a bonus on the Blu-ray disc, in which David Cairns applies auteur theory to track Dreyer’s career and the development of his recurring themes. It draws quite a bit from Jean Renoir’s essay and, like the film itself, this short video is rich and poetic.

It’s also quite amazing that, for this Masters of Cinema edition, Eureka have managed to dig up an archival interview with Carl Theodor Dreyer, from 1965 when he was aged 76. The audio interview was recorded when he was in America for the release of his final film Gertrude (1964), and he talks mainly about that film and his acknowledged masterpiece The Passion of Joan of Arc. He makes many a pertinent comment about most of his major works. His admission that, “I think it is not on purpose, but I have always been attracted [by] people’s sufferings, and in particular women’s sufferings…” might give us a glimpse as to why the narrative of Michael fascinated him.

director: Carl Theodor Dreyer.

writers: Thea von Harbou & Carl Theodor Dreyer (based on ‘Mikaël’ by Herman Bang).

starring: Benjamin Christensen, Walter Slezak, Max Auzinger, Robert Garrison & Nora Gregor.