UNBREAKABLE (2000)

A man learns something extraordinary about himself after a devastating accident.

A man learns something extraordinary about himself after a devastating accident.

Dating back to when it seemed like M. Night Shyamalan might become one of the greatest writer-directors of his generation, before his output became erratic and sometimes repetitive, Unbreakable is an intriguing complement to his breakthrough hit The Sixth Sense (1999).

Much like that paranormal chiller, Unbreakable features a downbeat Bruce Willis as a man who’s failed to comprehend the truth of his existence. It also again pairs him with a boy who does grasp what’s going on. And it devastates the audience’s assumptions at the end, in a twist the entire film’s been quietly hinting towards, while more overtly pointing at a different understanding of the situation.

But Unbreakable differs from The Sixth Sense as much as it resembles it. Most obviously, Unbreakable has a second strong adult lead in the shape of Samuel L. Jackson, whose character’s just as important to this tale while being more charismatic. (Indeed, it’s Jackson‘s role—not young Spencer Treat Clark—that corresponds to that of Haley Joel Osment’s from The Sixth Sense, despite Clark’s resemblance to Osment in appearance. It’s Jackson who enlightens Willis, as Osment did in Shyamalan’s previous movie.)

Equally importantly, whereas The Sixth Sense was about finding a resolution, Unbreakable is about a new beginning. Willis finds closure at the end of The Sixth Sense, but at the end of Unbreakable he’s about to embark on a new life. It’s an ending crying out for a cash-grab sequel, although Shyamalan didn’t continue the story until decades later in Glass (2019), which was more interested in Jackson’s character. Split (2016) is also tangentially a follow-up to Unbreakable, but Willis only appears briefly.

Unbreakable begins in 1961 with a baby boy being born in a Philadelphia department store. A doctor is summoned to assist and is shocked to report the infant already has broken arms and legs. Later we learn this was the birth of Elijah Price (Jackson), who suffers from a genetic disorder that makes his bones exceptionally susceptible to fractures.

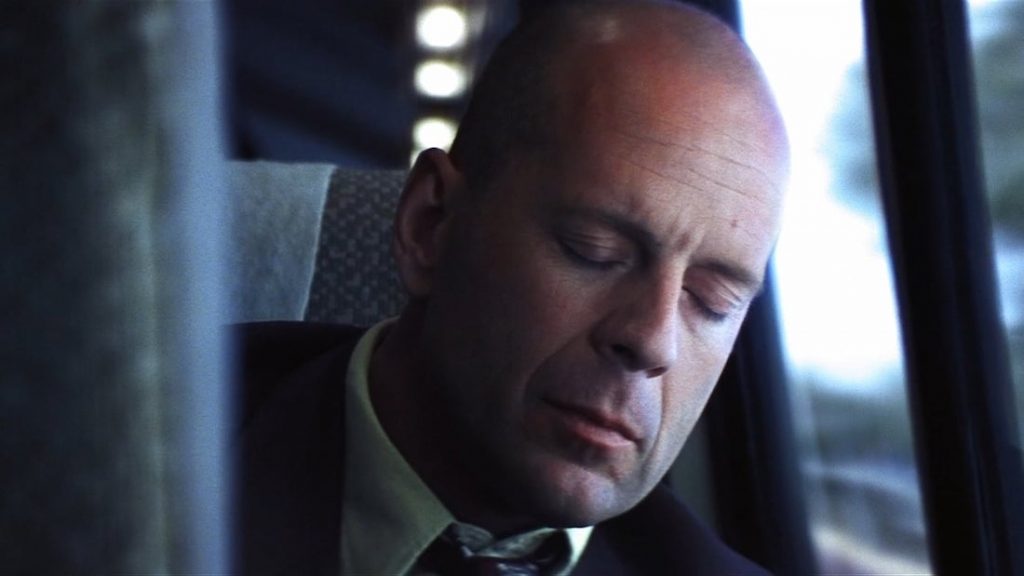

The film then switches to what’s recognisably the 1990s. A bored and unhappy looking David Dunn (Willis) is on a commuter train, when a young woman sits down beside him and he surreptitiously removes his wedding ring and chats with her. It comes to nothing and we get the impression David’s life is full of failed attempts to escape long-established confines.

Later, we learnt hat shortly after their conversation the train crashed (though we don’t see the event), with David being the sole survivor. “You didn’t break one bone,” a doctor marvels to him. The contrast with the shattered body of the infant Elijah is blindingly obvious.

It’s obvious to Elijah, too, as he quickly makes contact with David. Elijah’s theory, to which David is initially resistant to (unlike his young son), is that David has superpowers and can’t be physically hurt. Elijah reveals he’s been investigating disasters with only one survivor, reasoning they might be the invulnerable opposing force to his own extreme vulnerability. A successful dealer in comic-books, Elijah also has a theory they pass on a folk memory of real life superheroes, and he gradually makes David become aware of abilities he never knew existed in himself.

Unfortunately, Unbreakable isn’t entirely clear why Elijah believes comic-books are evidence of superheroes rather than works of imagination. There may be an element of wishful thinking on his part, but this idea is so much at the heart of the film that it’s disappointing it’s not fully developed. And that may contribute to the nagging feeling that Unbreakable, for all its style and beautiful filmmaking, isn’t wholly satisfying as an experience. As with The Sixth Sense, it’s almost entirely concerned with concept rather than developing a real “plot” in the sense of challenges, setbacks, and triumphs. Little in terms of anyone’s relationships or personal situations change from beginning to end, other than David’s better understanding of himself.

This can give Unbreakable the feeling of a static work, like a sculpture, more than a narrative. What we remember isn’t the way the story unfolds and broadens, but of a single idea linking events together. And a fundamental weakness in that idea (the lack of a coherent connection between the factual David and the fictitious comics) undermines the movie as a whole.

There are other weaknesses that make Unbreakable less than it might have been. The scene where David falls into a swimming pool (water is shown to be his “kryptonite”, as it was for the aliens in Shyamalan’s Signs) seems contrived, as does the ludicrous coincidence that Elijah is sent to David’s own physiotherapist wife Audrey (Robin Wright Penn) for treatment after an accident.

More broadly, the last act of Unbreakable is less engaging than what came before, thanks to the extended absence of Elijah. It’s Elijah’s interplay with David that gives the film its spark—and with Elijah kept offscreen for so long, the Dunn family’s story pales in comparison. This was perhaps an early hint of a problem affecting many of Shyamalan’s subsequent films: the notion that a great concept is enough to run with, and that if it’s sufficiently striking the nuts-and-bolts drama doesn’t matter too much…

But while its storytelling is sometimes iffy, Unbreakable is far from slapdash on a technical level. On a scene-by-scene and shot-by-shot level both the direction and the cinematography by Eduardo Serra is outstanding.

Shyamalan’s skill with a camera is also evident early on, best exemplified by a sequence in the train before it crashes. We see David about to fall into a doze, his eyes closing briefly, but then the train starts getting faster, the other passengers grow visibly anxious, and David comes back to alertness, his head turning in slow motion inside the hurtling carriage (though the sound of the clanging wheels remains just as rapid). It’s a brief, masterful encapsulation of a critical moment in a man’s life—perhaps the very instant prior to the crash—through the most mundane of actions.

Equally impressive is the aftermath of another accident, one that involved David as a younger man, shown in flashback. He’s asked “are you hurt?” and instead of hearing his reply, we see his mouth move and unmistakably form the ‘o’ of “no”. It’s one of the key lines of the movie, confirming that David is extraordinary. And yet putting so much meaning into a single, short, common word might be risky, as the audience might miss it. Instead, Shyamalan astutely draws our attention to what David is saying by not letting us hear it.

Indeed, there are many points where the way we see things is as important as what we see. When a young Elijah is introduced by his mother to the comic-books that’ll become his life’s passion, the camera watches from overhead as the boy unwraps a copy of Active Comics. He’s opened it such that it faces away from him, so he begins to turn it 180 degrees, while at the same time the camera, still pointed directly downward at the book, rotates 180 degrees in the opposite direction. The result is that although the page is coming into its correct orientation from Elijah’s point of view, for the audience it’s still upside-down and unreadable. And it’s then Shyamalan and Serra pull off their real coup: the boy stops moving the comic-book but the camera continues its own rotation through another 180 degrees, until we finally have the same perspective as Elijah. For us, as for this boy discovering the power of superhero stories, all is now clear. (This occurs 24-minutes into the film, if you want to check it out.)

Scene composition is often superb, too. It’s only a short while after this scene, in fact, that one of Unbreakable’s most commanding images occurs, when David and his son go to visit Elijah in the latter’s comic-book store. The building is grand and the scene’s shot so that Elijah’s framed by a magnificent arch—like a judge or king might be in classical art—with a panel of hieroglyphics behind him (also arch-shaped), reminding us that the communication of myth through drawing long predates the era of DC Comics and Marvel.

Here, David sits in front of Elijah, his back to the audience, like a supplicant. But the shot is echoed minutes later by another in the football stadium where David works as a security guard, and now both Elijah and David are standing together with an arch in the background, although it’s Elijah who’s dead-centre within its curve while David is slightly off to the side. They’re slowly becoming equals, though Elijah still dominates. Indeed, this visual theme may be deliberately referenced yet again in a much later scene at David’s home, where several arches form a more complicated, even confusing backdrop to a conversation between him and Audrey. Real domestic life is ambiguous in a way that superheroics aren’t.

None of this is to imply that Unbreakable needs scrupulous visual decoding; there’s symbolism in the photography, undoubtedly, but it adds depth rather than being essential to enjoying the film. So do Serra’s frequently inventive (but never intrusively wacky) camera angles, and the painterly use of colour—whether in the grading of a scene or the clothes of one person—that lends grandeur and significance to the drab and unspectacular Philadelphia settings, as befits a superhero tale. (“These are mediocre times,” says Elijah.)

In the same way, Unbreakable’s many long takes (a reported 30 single-shot scenes) help create an atmosphere of solemnity and importance, as do the Old Testament names of David and Elijah.

Competing with all this, and with only a terse script to exploit, the acting doesn’t have much of a hope of standing out, though all four of the main players do their best. Jackson has the flashiest role and delivers it with the panache one would expect, rendering Elijah as intellectually assertive while physically cautious. Willis plays David in the opposite way—browbeaten by life, seemingly only confident in the context of work. It’s a departure from this actor’s famous action heroes which underscores Unbreakable’s central idea of a superhero who doesn’t realise he should be behaving heroically.

Clark, meanwhile, is convincingly frustrated as a young boy who believes in his father’s greatness before his father does, and Penn is affecting as David’s wife sadly coming to terms with the fact her marriage is ending—though her part is underwritten. Still, she gets Unbreakable’s funniest line (in a film with more humour than one recalls), during the best of the family scenes, where David’s son suggests shooting his dad to prove he can’t be injured.

Shyamalan himself appears in a small cameo, as he does in many of his movies, playing a drug dealer questioned by David in the stadium.

Unbreakable did decent business (grossing $248M from a budget of $75M), though it wasn’t a cultural phenomenon on the scale of The Sixth Sense (which grossed $672M and only cost $40M to make). Critics felt it didn’t live up to the promise of its predecessor, despite being an entertaining film. Today it stands up adequately, even if it’s the kind of movie that loses some emotional power once you know the twist.

What it isn’t, though, is a great movie. There’s flair to the filmmaking and a potent underlying idea, but once that idea is revealed, Unbreakable wastes time parading it over and over again and never moves forward or develops the story or its characters. This lack of progress isn’t utterly fatal because Unbreakable is never boring, and so many individual scenes are absorbing, but it’s so dependent on the premise and the twist that those two things are what one takes away from it. Everything else seems like colouring-in the conceptual outline.

USA | 2000 | 106 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: M. Night Shyamalan.

starring: Bruce Willis, Samuel L. Jackson, Robin Wright, Spencer Treat Clark, Charlayne Woodard, Eamonn Walker & Leslie Stefanson.