THE KNICK, 2.1 – ‘Ten Knots’

In its first season, The Knick was a series more interesting than it had any right to be. Set during the turn of the 20th-century at an early New York hospital, the Knickerbocker, it could so easily have been Holby City with period costumes; another soapy medical drama with only a unique setting to differentiate it from the Grey’s Anatomy’s of this world. But under the masterful direction of Steven Soderbergh, The Knick became a far more auspicious beast. Yes, the set-up may be familiar—Clive Owen’s Dr. John W. Thackery is yet another flawed, white, male genius protagonist—but in its presentation, The Knick struck dramatic gold.

First, the situation since last season:

As a result of his crippling cocaine addiction, ‘Thack’ has been institutionalised in a specialist hospital for addicts, which are treating his dependency with an experimental wonder-drug—um, heroin. With a fresh addiction to deal with, Thack is out of action for the long-term, and Dr. Edwards (Andre Holland) is acting Chief of Surgery at the Knick, despite suffering ocular difficulties as a result of his street fighting. As a black man in 1901, Edwards’ position is much to the continued chagrin of chief-expectant Dr. Gallinger (Eric Johnson) and most of the rest of the hospital heads, who also lump Dr Bertram ‘Bertie’ Chickering (Michael Angarano) with a hopeless new doctor who’s nevertheless well-connected to the city’s upper class, as medical and financial needs continue to clash.

Cornelia Robertson (Juliet Rylance), meanwhile, has been whisked away to San Francisco with the husband she doesn’t want, where she tries alleviate the strife of people trapped behind quarantine in Chinatown due to an outbreak of bubonic plague; while Sister Harriet (Cara Seymour) finds herself in a women’s penitentiary as a result of her illegal abortion clinic.

As is often the way with shows, The Knick’s second season opens with plenty of altered circumstances for our characters, but the show is rather too keen on quickly resetting the board. As such, by the end of this first episode, Cornelia is already back in New York, and Thack’s out of hospital and on his way back to work at the Knick, having been kidnapped and forced to go ‘cold turkey’ by Gallinger aboard a sailing ship. It might have been nice to explore those characters in their new situations for a little longer—say, learn more about Thack’s ad hoc, improvised surgeries in exchange for vials of heroin at the hospital, or Cornelia’s frustration at being forced out of the job she loved. Of course they’d never have been away from the titular hospital for long, but this seems like a wasted avenue.

Plot, though, has never been the main selling point here; it’s in the look, the feel, and the sound of the show that The Knick truly comes alive. Soderbergh’s camerawork is exceptional, while Cliff Martinez’s electronic score is a thing of anachronistic perfection. Soderbergh often shoots scenes from unconventional angles and positions, leaving characters out of focus or concealed and obstructed, or even out of the shot altogether. For example, when detailing his successes as acting Chief of Surgery, we only see the back of Edwards’ head, because Soderbergh knows that watching him delivering this speech isn’t what’s interesting—it’s in the reactions of those hearing it.

At times, Soderbergh also takes the opposite tack, and lingers solely on the face of one character for an extended period, such as when the camera dwells on Cornelia while her husband and father-in-law discuss uprooting her life once more off-screen. We don’t need to see their faces—this isn’t their moment—and keeping tight on Cornelia (or any character) allows for a much greater opportunity for these actors to show what they can do.

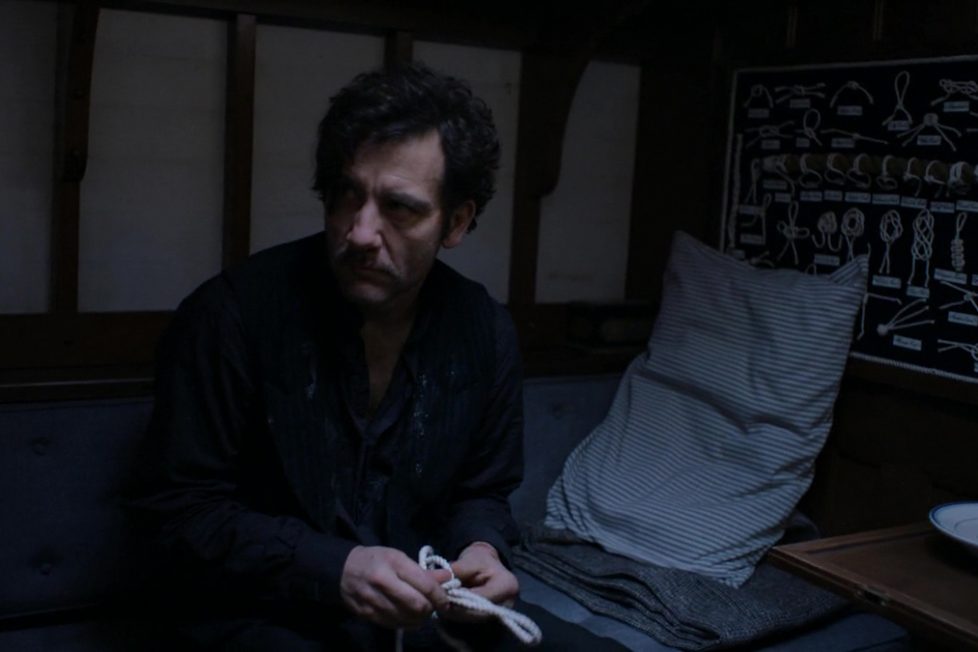

As the show’s anchor, Clive Owen continues to work wonders as Thackery, a man who’s addled as much by the myriad ideas and inspirations charging around in his brilliant head as he is by the drugs that he needs to function. Owen’s performance is unglamorous and extremely committed, and the scenes on Gallinger’s boat are a great showcase for him. While showing Thack in the throes of a heroin high allows Owen to have fun with the physicality of the role—all twitches, pacing and barely controlled mania—it’s in the more emotional areas that this episode’s best moment comes. “The need will never go away”, Thack sobs pitifully, lying in withdrawal on the floor of Gallinger’s boat. It’s pathetic and heartbreaking and perhaps the most vulnerable we’ve ever seen him.

Soderbergh’s avant-garde style of filming also lends the show a real air of authenticity. At times, the camera will follow a character down a corridor, but then stop at the door when they enter a room, filming from the outside. It gives the entire series a voyeuristic, documentary feel; which, coupled with the horrifyingly realistic surgery scenes, makes The Knick a particularly striking piece of television. And be warned—the scenes of surgery in 1901 are still horrifyingly portrayed. Whether it’s Thack chiselling a woman’s nose back into place, or Bertie draining what seems like litres of pus from an abscess, The Knick often makes for startlingly grim and difficult viewing. (When Edwards asks for an experimental procedure to fix his eye problem, the potential horrors ahead don’t bear thinking about…)

But it’s not just the incredible make-up and prosthetics that bring this world to life—Martinez’s score adds incredible vibrancy to proceedings, helping create a period show that’s as far from fusty Downton Abby-style prestige dramas as you could possibly get. Take the scene where hulking Irish paramedic Tom Clearly (Chris Sullivan) is seen hosting underground street fights: the sequence features no sound from the scene whatsoever, with only the propulsive percussion and tremulous synth of Martinez’s score to colour the moment.

Trusting the score to convey the required atmosphere is a great way to go—simply because so many other shows simply wouldn’t make that choice. It’s a far more interesting way of presenting the sequence than simply accentuating the roar of the crowds, or the impact of the punches. The Knick has a way of presenting scenes that might otherwise be conventional in pulsating and innovative ways that really bring the show to life.

The Knick still has its share of problems, of course: a surplus of characters being chief among them. Nurse Elkins (Eve Hewson) remains a resolutely uninteresting figure, both as written and as performed by the young actress, and there’s a tendency to lean too heavily on Jeremy Bobb’s hospital manager Barrow, who’s important as our window into the upper echelons of the Knick’s management, but who doesn’t command the screen as much as the supporting cast.

This first episode ends with a groundbreaking ceremony for the new Knickerbocker Hospital, the development of which will likely be one of the main threads running through the season. And while The Knick may not be groundbreaking in the stories it wants to tell, the vibrant way it tells them is utterly captivating, and that’s makes this show unmissable.