THE BREAKING POINT (1950)

When his boating business starts to fail, a family man turns to crime.

When his boating business starts to fail, a family man turns to crime.

Any list of beloved movies from Hollywood’s Golden Age will surely feature Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca (1942) near the top, yet his role as director is largely overshadowed by the performances of Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. Similarly, his many successful collaborations with Errol Flynn (1935’s Captain Blood, 1940’s The Sea Hawk, etc) are usually thought of primarily in terms of their star, just as Mildred Pierce (1945) is considered a Joan Crawford vehicle and Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942) one for James Cagney.

Curtiz’s immense versatility during his long career with Warner Bros. has worked against his reputation, in a way. There’s no obviously recognisable “Curtiz style”, no overriding “Curtiz themes”, and yet he gave us, with consummate craftsmanship, so much fine work—of which The Breaking Point is yet another example.

Curtiz here turns to noir (the film was at one point intended to be called Winner Take Nothing) and elicits smouldering performances from John Garfield and Patricia Neal while telling a tight, compelling tale and providing a strikingly realistic, nuanced portrayal of a marriage that’s both strained and still loving.

The Breaking Point is based on parts of Ernest Hemingway’s 1937 story To Have and Have Not, relocated here from Florida to California but still sticking somewhat closer to the novel than the 1944 Howard Hawks/Bogart/Lauren Bacall film adaptation.

An opening voiceover—which will reappear at a few key points—introduces us to Harry Morgan (Garfield), the skipper of the fishing charter boat The Sea Queen, observing that life is calm at sea but troubled on land.

We soon enough see examples of this: at the marina, he’s denied credit for fuel, and his wife Lucy (Phyllis Thaxter) has similar problems at the local store. It becomes apparent that Harry’s business is faltering, but when Lucy encourages him to try another line of work—perhaps on her father’s farm—he’s adamant he belongs at sea and carefully, respectfully, straightens a photo of a naval craft.

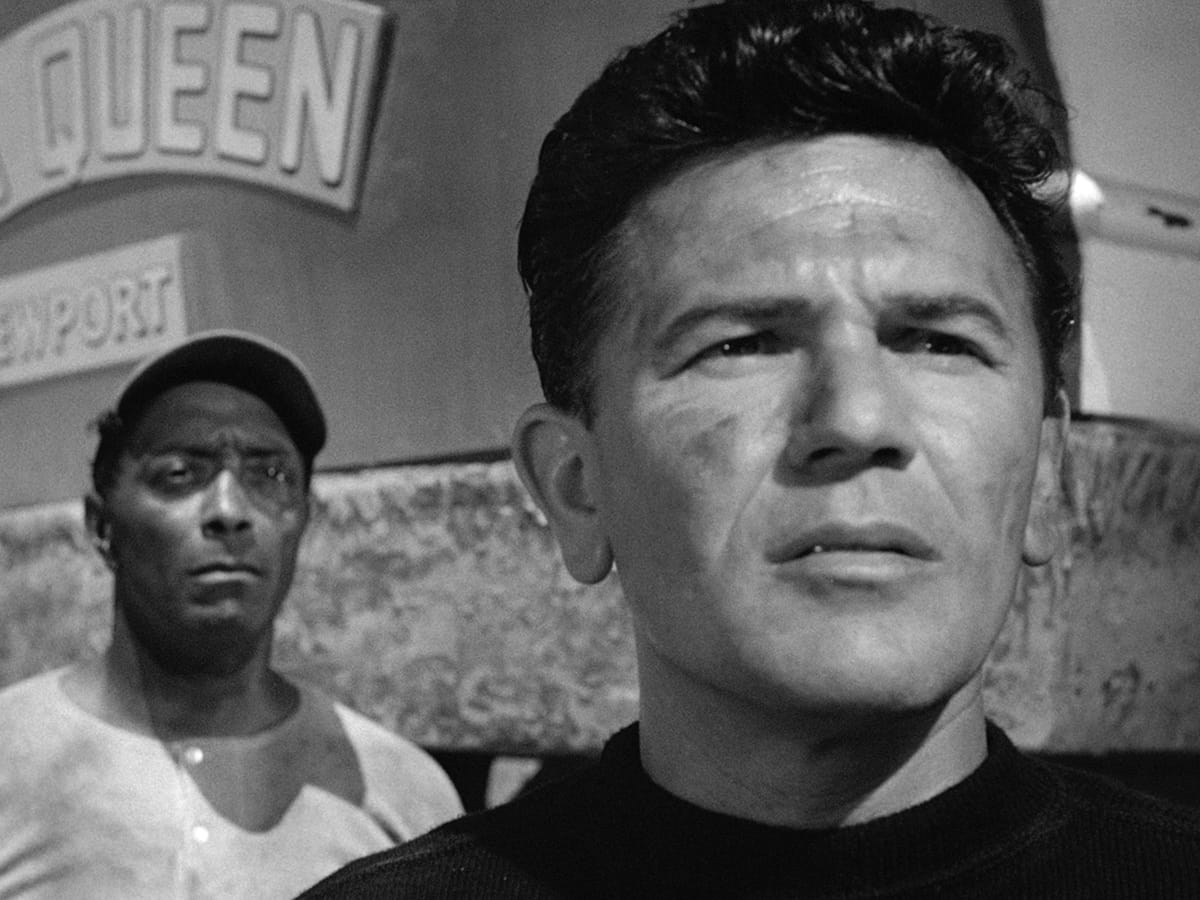

Harry, we realise, is a veteran who’s having a hard time adjusting to civilian life. Paying the bills and raising their two daughters is “the biggest war there is”, Lucy insists, but although it’s clear his relationship with his family is genuinely close, nevertheless he refuses to compromise. Indeed, this stubbornness will lead Harry to be sharp and deceptive both to his wife and to his long-standing friend and colleague Wesley (Juano Hernandez); and while later he’ll say, twice, that “a man alone ain’t got no chance”, for much of the movie his pride seems to prevent him from recognising this.

He and Wesley take a client, Hannagan (Ralph Dumke), and his younger blonde friend Leona (Neal) on a fishing expedition to Mexico, though one might suppose that angling is not the main thing on Hannagan’s mind. This customer will soon disappear from the film, but first he sets events in motion by abandoning the two boatmen and Leona in Mexico without paying his bill.

Harry now doesn’t even have enough cash to make it back to California, and so he accepts a questionable job from a corrupt lawyer whom he runs into at a bar, Duncan (Wallace Ford). This foray into people smuggling (helping Chinese immigrants, not Mexicans, evade the border controls— a sign of the film’s age) doesn’t go well, but Harry becomes further enmeshed in crime and also further entangled with Leona…

In narrative terms, The Breaking Point isn’t always what one expects. Harry’s acquaintance with Leona doesn’t develop instantly into the anticipated affair, and indeed it’s debatable whether either of them really wants anything more than mild flirtation.

Instead, his credible and unmelodramatic marriage remains the emotional focus of the movie. Indeed, the film’s producer, Jerry Wald, opined that “what makes The Breaking Point attractive to us is the freshness of having your leading man love his wife and children and not jump into the nearest bundle of hay with any dame that flops her cap in his direction.”

“Usually, when a man tells me he loves his wife, it ends up with ‘but’…,” says Leona… but there’s no “but” here. Harry does love his wife, as does she; their tragedy lies in the gulf between what she actually wants (a stable family life) and what he feels he has to provide (everything).

It’s depicted as a marriage of equals, more explicitly than was common in films of the time. “You act like you’re all alone,” Leona says. It’s this that drags him into crime (people like Harry are honest until they get into a jam, Duncan comments).

But it’s also, even if the topic isn’t openly discussed much in The Breaking Point, his difficulty in adapting to the peacetime world that makes Harry so determined to self-destructively go it alone when Lucy would gladly stand alongside him in a more cooperative effort to solve their problems. More broadly, as well, The Breaking Point may allude not only to the difficulties of veterans but to the sharp separation in 1950s men’s lives between the worlds of work and home.

All three of the leads are outstanding. Neal as Leona, described by Curtiz’s biographer Alan K. Rode (who appears on this disc’s extras) as “a cinematic harlot for the ages”, is magnificent: her face full of meaning, transforming from relaxed jocularity to hard wariness in a moment, subtly but tellingly rejected when Harry pulls back from a kiss. There is a touch of innocence to her, too, even at her most conniving moments, which gives Leona a depth and freshness some femmes fatales of the period lack.

Thaxter as Lucy is equally powerful in a less extravagant role—an episode where she dyes her hair blonde to compete with Leona is affectingly sad, but she never comes across as pathetic or anything less than strong and intelligent. Garfield, meanwhile, is completely convincing as a man impelled to do things he would not really choose to do, whose deceptions and brutalities are forced on him by his situation.

Among the character roles, Ford is terrific as the lawyer Duncan—scheming, cajoling, cynical, cowardly and ultimately a victim of his own corruption. Sherry Jackson (near the beginning of her career) is sassy and funny as the Morgans’ younger daughter, while Hernandez as Harry’s crewman provides a figure of straightforward decency to contrast with the troubled protagonist.

Hernandez’s role in The Breaking Point is interesting too. At first, he seems to add relatively little, as the film ends with his young son, implying Curtiz and Ranald MacDougall were aware of the character’s symbolic significance. Rode has also argued that Curtiz was unusually proactive for the time in casting black actors; the Afro-Cuban Hernandez, who appeared in the director’s Young Man With a Horn in the same year, suggested that “if the Negro is portrayed as a real human being on the screen, that does more than anything to make him and his problems come alive”. Real he certainly is in The Breaking Point.

Curtiz was never the kind of director to draw attention away from the players and the story toward his directing, but though The Breaking Point is unflashy it’s full of visual interest and variety (drapes and shadows in Leona’s apartment; Harry silhouetted against the setting sun).

The narrative always moves quickly (back in Hungary, Curtiz—when he was still Mihály Kertész—-had spoken of the need for concision and rapidity in filmmaking) and the dialogue is also to the point, even hard-boiled in its brevity at times. A racetrack robbery near the end is edge-of-the-seat stuff, and a gun battle on The Sea Queen is expertly choreographed.

But more leisurely sequences (for example Leona and Lucy’s encounter in a bar, or conversations at home between Harry and Lucy) are equally timed to perfection. The many scenes on board Harry’s boat, meanwhile, convince the viewer that they’re really taking place on the water, right down to the small to-and-fro movements of the craft.

The Breaking Point might have been one of the bigger films of the year but ambitious launch plans were quickly scuppered when Garfield was outed as a supposed Communist sympathiser by Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television. His Hollywood days were over and he died two years later, aged only 39.

Curtiz’s long directorial career was approaching its close, too, and although he would continue to have successes over the next decade such as White Christmas (1954) and King Creole (1958), The Breaking Point was one of his last great movies. It may not have the instant name recognition of earlier Curtiz work but it deserves to, and Criterion’s reissue is an attractive package with a couple of very worthwhile extras.

USA | 1950 | 97 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Michael Curtiz.

writer: Ranald MacDougall (based on the novel ‘To Have and Have Not’ by Ernest Hemingway).

starring: John Garfield, Patricia Neal, Phyllis Thaxter, Juano Hernandez & Wallace Ford.