THE SWORDSMAN OF ALL SWORDSMEN (1968)

Two highly regarded, yet underseen martial arts movies from director Joseph Kuo are presented together for the first time by Eureka Entertainment. Still feeling fresh with its seamless blending of chambara and wuxia, The Swordsman of All Swordsmen / 一代劍王 (1968) has been digitally restored by the Taiwan Film Institute from a 2K scan of the best-surviving elements, while The Mystery of Chess Boxing / 雙馬連環 (1979) has been nicely cleaned up from a scan of the only known complete print of the cult classic.

While the latter is ostensibly included as bonus material, it’s revered as a prime example of the director’s many kung fu films—and is likely to be the main draw for fans hoping to relive their youthful enjoyment of it, alongside newcomers who only know it by reputation and its enduring pop culture legacy, inspiring songs by the Wu-Tang Clan and a favourite of one member, Ghostface Killah.

The film was a sensation in the US, enjoying a 10-year theatrical run in New York’s Times Square, but was largely forgotten by the 1990s when all but one of the distribution prints had presumably worn out. The source Eureka used for this high-definition scan was held in a private collection and is the international print with burnt-in dual-language subtitles.

Prolific writer, director, and producer Joseph Kuo (郭南宏) is among the most important figures in the history of Taiwanese cinema. However, he remains best known for action films made throughout the 1970s and 1980s with Hong Kong’s legendary Shaw Brothers Studios. Kuo began his long career in the mid-1950s by reworking his unpublished novels into screenplays. This was the dawn of the Taiwanese-language movie industry when there was a dearth of home-grown talent.

After selling his second screenplay, Ghost Lake (鬼湖) (1958), he was also invited to direct it, marking his feature film debut. At just 23 years old, the film was a resounding success. Over the next decade, he went on to direct at least 25 romantic dramas. Sadly, all but a few of these films are now lost or were deliberately destroyed. This destruction occurred during the Republic of China’s attempt to modernise the nation under post-war martial law. The aim was to eradicate the use of native dialects in favour of Mandarin. However, films promoting traditional values, including the chivalrous honour codes of ancient China, were actively encouraged. This paved the way for Taiwan’s action genre, with seminal director King Hu at the vanguard.

King Hu’s groundbreaking martial arts film, Come Drink with Me / 大醉俠 (1966), popularised modern wuxia and inspired Kuo to change tack. Reportedly, within a week of seeing it, Kuo had written his first martial arts script and sold it to Taiwan’s Union Film Company, where Hu’s follow-up, Dragon Inn / 龍門客棧 (1967), was also in production. The result was The Swordsman of All Swordsmen, an elegantly simple revenge story with a subtle philosophical subtext.

Over the next 20 years, he would establish himself as one of the most respected action directors working in Hong Kong. He secured a collaborative contract with Shaw Brothers Studios, while also making films in his homeland through his own independent production company, Hong Hwa International.

Unsurprisingly, the quality of his films varied. Many were shot on tight budgets and schedules, destined to be quickly forgotten. However, others achieved cult classic status and are recognised as significant influences on the Asian action genre. Across his three-decade career, he directed an impressive 75 films, although many of his earlier Taiwanese-language works are omitted from most filmographies.

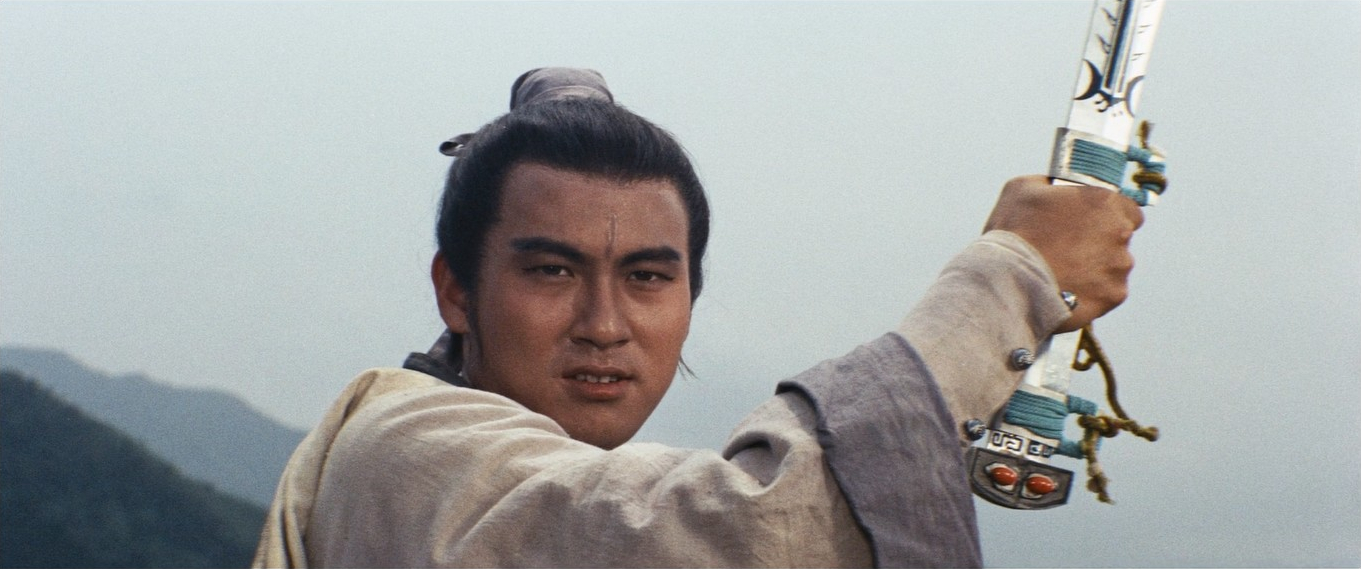

Tsai Ying-Chieh is on a 20-year-long mission of revenge against the man who killed his parents, and anyone who gets in his way must be punished by his swordplay skills.

For those who would be thrilled by a skilful fusion of chambara and wuxia, this early example from a master of the genre will be met with eager anticipation. If such terminology leaves one bemused, then Joseph Kuo’s The Swordsman of All Swordsmen is the ideal place to start. The action sequences are excellent, and the lean narrative is delivered with panache right up to its poetic and profound finale.

In essence, chambara are Japanese period dramas that focus on swordplay and typically feature samurai or ronin. Wuxia (pronounced Woo-She-Ah) is the Chinese equivalent, although it’s usually set in a mythologised past and prominently features fantastical elements bordering on the supernatural. Considered the elder genre in Chinese arts and literature, examples of wuxia can be traced back millennia, predating the very concept of genre itself.

As the rousing strains of André Previn’s theme for The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962) blare during the dynamic opening titles, a lone horseman gallops through the scene. The score continues to lean heavily on music lifted from Hollywood films, perhaps offering a familiar element for international audiences.

The rider turns out to be Tsai Ying-jie (Peng Tien), who arrives at a walled town just in time to witness a deadly altercation. Chou Hu (Miao Tien), a locally renowned fighter, has just dealt a fatal blow to a mild-mannered street performer (Ming Kao) simply to have his way with the man’s young daughter, Pearl (Meng-Hua Yang).

Initially, Tsai Ying-jie comes across as though he’s been cast from the same mould as a traditional Western hero—the lone gunslinger who rides into town just in time to rescue a damsel in distress. Only here, it’s swords, not pistols. However, things take a turn. After a display of impressive swordsmanship, Chou Hu finds himself pinned to a tree by his own blade. Through the dialogue during the fight, we learn that Tsai Ying-jie’s true motive for being there was to kill him.

With his dying breath, Pearl’s father pleads with Tsai Ying-jie to look after his daughter. He arranges for her somewhere to stay and, although there’s a hint of a potential romance, explains that he must continue his quest for vengeance before leaving. At his belt, he carries a set of tablets inscribed with the names of the men he witnessed murdering his family some 20 years earlier. Since then, he’s lived for revenge, focusing only on training and honing his swordsmanship. As each victim is dispatched, he breaks the tablet bearing their name. This is a simple but effective device that helps pace the film with an inexorable countdown.

The odds become considerably worse when he encounters his second target, Fang Bao (Ko You-min), who’s guarded by scores of henchmen. The ensuing fight sequence is brilliantly executed, featuring ambitious tracking shots that follow the action from the courtyard of a martial arts school down through dense rushes to a riverside. With so many opponents, it’s a close call, but ultimately, he emerges victorious, once again using his opponent’s sword against them. However, his success might not have been possible without the intervention of a mysterious figure wearing a hat filled with deadly shuriken—tiny, razor-sharp throwing blades. This individual turns out to be Black Dragon (Nan Chiang), who holds the title of ‘Sword King’—similar to the Japanese honour of being proclaimed Kensei, the undisputed master of the sword. This title, however, can only ever be held by one person at a time.

Tsai had attracted the attention of Black Dragon after news of Chou Hu’s death at the hands of a skilled swordsman reached him. Now, having witnessed this newcomer defeat multiple opponents—including the one who ran the local training school—he doubts his own worthiness of the title. With great respect and courtesy, he challenges Tsai to a duel to the death, to determine who truly is the greatest swordsman. Tsai graciously accepts but requests a postponement to complete his current mission—avenging his family’s murder.

This isn’t the only trope that might be borrowed from the Western genre. It’s unclear whether the influence of Italian Westerns is direct, or whether it comes via Japanese chambara films, which Kuo was known to be an avid viewer of. There are some strong similarities with Hideo Gosha’s classic Samurai Wolf (1966-67) duology that seem too close to be entirely coincidental. In particular, there’s the presence of this honourable master swordsman, intent on pitting his skills against the protagonist and repeatedly delaying the duel. Gosha was known to be inspired by the Westerns of Sergio Leone, but both Gosha, Leone, and indeed Kuo, all cite Akira Kurosawa as their major influence.

The next two tablets bear the names Liu Xiang (Shih Lu) and Yin Shi (Han Hsieh). These men seek out Tsai of their own accord, intending to outnumber him in the confined space of an inn while he dines. This is where the more supernatural aspect of his prowess is revealed. He holds down a table with one relaxed arm, continuing his meal as four or five henchmen strain in vain to overturn it. Then comes the almost obligatory use of chopsticks as a weapon, followed by another expertly planned fight scene of impressive complexity, vividly conveyed. However, Tsai’s opponents here are the least honourable encountered so far, resorting to underhanded tactics with concealed archers and poisoned arrows. Luckily, his new nemesis, Black Dragon, intervenes once more, alongside his clan companion, Flying Swallow (Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kuan).

So far, the plot has been straightforward, and the characters haven’t shown much depth or development. We’re about halfway through when things become interesting, and a subtle subtext begins to emerge.

During the recovery episode—perhaps referencing Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) or Sergio Leone’s loose remake A Fistful of Dollars (1964), or both—Tsai discusses his motivations with the insightful Flying Swallow, who questions his lifelong obsession with an honour code that demands a life for a life. They also delve quite deeply into comparing the relative merits of gratitude and revenge, as both involve owing debts.

Later, we learn that Flying Swallow is the daughter of Yun Chung-Chun (Chien Tsao), the old man whose name is on the final tablet held by Tsai…

This was Peng Tien’s first starring role following his big-screen debut in Dragon Inn, which was also the debut of its star, Polly Ling-Feng Shang-Kuan. They weren’t the only members of the ensemble cast who appeared in several films together under the direction of either Kuo or Hu. All were under contract to the Union Film Company, making Taiwan the epicentre of the 20th-century wuxia revival.

If we’re being picky, there are a couple of minor flaws. The main one is a fumbled reveal where Tsai hasn’t grasped a key detail that’s painfully obvious to the viewer. However, this is a minor quibble and is more than compensated for by the astonishing camerawork, entertaining action, well-rounded performances, and superb fight choreography. With deceptively simple storytelling and understated emotional depth, The Swordsman of All Swordsmen remains a thoroughly worthwhile and ultimately satisfying experience.

TAIWAN | 1968 | 85 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | MANDARIN • ENGLISH

Supposedly dead, embittered former official The Ghost Face Killer has returned and is seeking revenge on those martial arts masters thatonce opposed him…

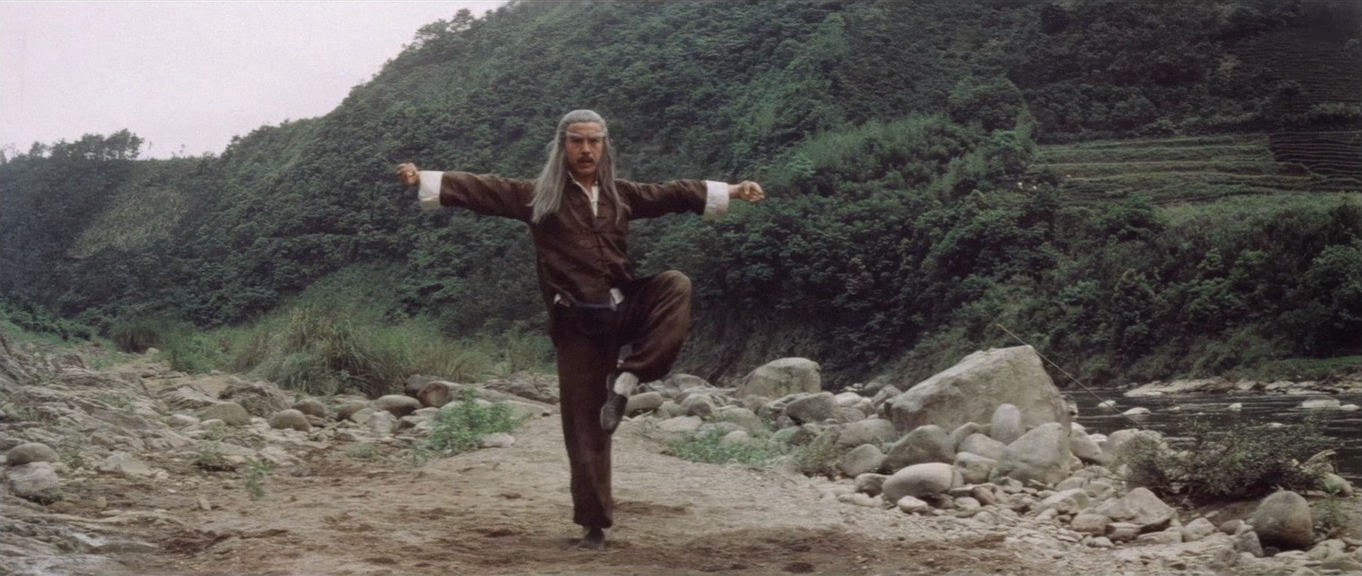

The mysterious Ghost-Faced Killer (Kuan-Wu Lung) challenges Chao Yun-Lung (Chi-Sheng Wang) to a duel to the death. However, he allows his opponent’s wife and child to escape before performing a solo exhibition of kung fu forms. Both men possess impressive fighting skills and clearly have a history together. Despite Chao Yun-Lung’s outward appearance as a humble fisherman, he displays formidable kung fu. However, the outcome proves him to be a surprisingly easy kill.

Having established our villain’s credentials with this enigmatic, action-packed opening scene, the first act takes a comedic turn. Young Ah Pao (Yi-min Li) joins a temple and is immediately targeted by one of the senior students (Hou-Tao Hsiao). However, Ah Pao sees the relentless bullying as a learning opportunity. When forced to serve his seniors in the canteen before getting any food himself, he simply throws himself into the task, becoming ever faster at serving rice. He juggles empty bowls and flips full ones back to the tables with impressive dexterity. Rather than looking inept, his antics earn him grudging respect, and eventually, friendship, from his fellow students. This positive attitude catches the eye of the cook, Yuan (Siu-Tin Yuen), who turns out to be a martial arts master in disguise. Yuan agrees to train Ah Pao in exchange for his help with kitchen chores.

This is a joyful pick-and-mix of everything the Asian martial arts genre offered in its 1970s heyday, unafraid to blend comedy with violence. The performances aren’t award-worthy, but respect is due to those acting through unconvincing wigs, glued-on eyebrows, false beards, and token attempts at ageing make-up. Everyone delivers what the story needs, and the often rice-based physical comedy is superb—particularly the scene where Yuan nonchalantly continues eating his bowl of rice after challenging Ah Pao to steal just a single grain.

There are so many stand-out set pieces where the stunt choreography—brutal or comedic—is as good as it gets, with minimal use of springboards or wires. Some scenes do utilise frame-removal to speed up the action and make the moves even sharper, but generally what we’re witnessing are highly skilled martial artists showcasing inventive combinations of styles that can make a simple fight between two men in a field truly gripping. All are accompanied by loud impact sound effects that, of course, don’t always coincide with the blows. The death matches are so ludicrously OTT that they can’t be taken seriously. Opponents spout proverbs between blows and provide running commentaries on what moves they’re using— but that’s exactly what one wants from this golden age of kung fu cinema!

The action sequences were choreographed by Joseph Kuo, a veteran of the genre by now, having directed at least 40 films since The Swordsman of All Swordsmen—that’s an average of four per year. Here, he collaborates with three experienced fight choreographers who also appear on screen. Chi-Sheng Wang plays Ghost Faced Killer’s first on-screen victim; Tien-Chi Cheng takes on the role of a kung fu student tasked with teaching Ah Pao a lesson upon his arrival in the temple courtyard; and Yung-sheng Wang demonstrates the discipline of pole-fighting before falling victim to the Ghost-Faced Killer.

Many of the stunt performers working in Hong Kong action films trained at the Peking Opera—performing arts schools that teach martial arts, acrobatics, singing, dancing, and other physical stagecraft. Yi-Min Li isn’t the only graduate of Taiwan’s equivalent, the Fu Xing Ju Xiaosta, to star here.

After a misunderstanding leads to Ah Pao’s expulsion from the temple, the cook recommends that he seek out another Kung Fu master to continue his rigorous training. Played by fellow Fu Xing Ju Xiaosta alumnus, the grey-haired Chu Tzu Chen (Shi-Chia Lung) is reluctant to take on a pupil until his granddaughter (Jeanie Chang) convinces him otherwise. So, Ah Pao’s second stage of training commences… with months spent solely playing chess to learn calm control, analytical thinking, and that every move has a countermove. Only then can he begin with some eye-watering stretching exercises that look more like methods of torture.

By now, the perfectly paced first hour has whisked by. It’s not until the close of the second act that we finally grasp the interconnected motivations of all the characters. Ah Pao clings to the hope of one day avenging the brutal murder of his father, which he witnessed as a child. He carries a painted bronze medallion—a chilling calling card left by none other than the Ghost-Faced Killer, who’s also motivated by vengeance. We learn that Chu Tzu Chen was one of five kung fu masters who knew the man as a corrupt government official. They banded together in a failed attempt to eliminate him.

His backstory suggests the Ghost-Faced Killer profited from the decline of the Qing dynasty following the mid-19th-century Opium Wars, deliberately provoked by foreign powers to destabilise internal affairs. His presence might be symbolic of these foreign powers, intruding upon his victims’ lives and bringing violence and death. While the exact period isn’t specified, five Masters recall the Ghost-Faced Killer as a corrupt official during the decline of the last imperial government, marking the end of the Qing era.

We learn of his ruthlessness, as he orders the executions of anyone who hinders his profiteering. There’s a hint that he might have been instrumental in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, with the Masters and their disciples possibly being revolutionaries. But that’s all the historical context we’re given, which takes a backseat to the exhilarating, near-constant displays of martial arts as the Ghost Face Killer hunts down his enemies living incognito, desperately trying to outrun their past. We know he’s on a collision course with Chess Master Chu Tzu Chen, and, of course, the inevitable final throwdown with Ah Pao looms.

TAIWAN • HONG KONG | 1979 | 91 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | MANDARIN • CANTONESE • ENGLISH

director: Joseph Kuo.

writers: Joseph Kuo & Tien-Yung Hsu (based on a story by Shui-Han Chiang) (Swordsman) • Joseph Kuo (Boxing).

starring: Polly Shang-Kuan Ling-Feng, Tien Peng, Yang Meng-Hua, Chiang Nan, Tsao Chien, Wei Su & Tien Miao (Swordsman) • Yi-Min Li, Shi-Chia Lung, Kuan-Wu Lung, Siu-Tin Yuen & Jeanie Chang (Boxing).