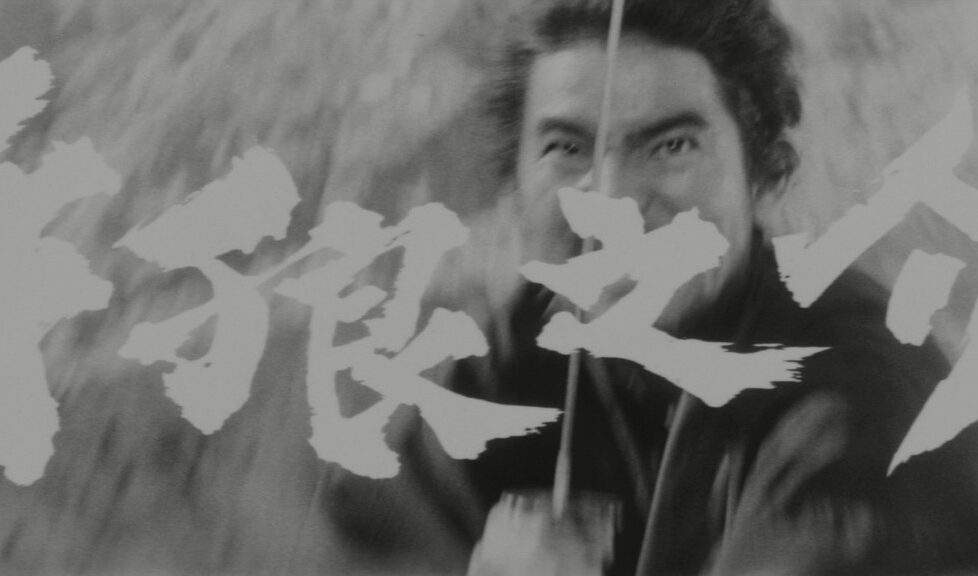

SAMURAI WOLF 1 & 2 (1966-67)

A duo of chanbara masterpieces from one of the genre's greatest directors, Hideo Gosha.

A duo of chanbara masterpieces from one of the genre's greatest directors, Hideo Gosha.

Think of an influential Japanese director… odds are, I can guess which one. Anyone not put off by black-and-white movies from 1960s Japan will have no difficulty in enjoying this double bill of what director Hideo Gosha referred to as ‘Mount Fuji Westerns’. A breath of fresh air for the rapidly tiring chanbara, he was drawing from several earlier examples, but there’s more to the genre of samurai cinema than Akira Kurosawa’s classics. With his innovative Samurai Wolf duology, Gosha mixes in many traits from Italian Westerns, completing a sort of feedback loop between the cinema of Hollywood, Asia, and Europe.

The Western is the oldest genre, enjoying its Hollywood heyday with films like High Noon (1952) and Shane (1953)—both known to have impressed Akira Kurosawa, inspiring him to rework similar tropes in Seven Samurai (1954), which was then reiterated by John Sturgess as The Magnificent Seven (1960) in the US. Then Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) was remade by Italian pulp director Sergio Leone as Fistful of Dollars (1964), making a global impact by re-mythologising the American West.

In turn, Hideo Gosha was inspired by Kurosawa’s stylish, western-influenced samurai movies to develop a chanbara series for Fuji Television. It proved so popular he was commissioned to make a cinematic adaptation, under the same title of Three Outlaw Samurai (1964), where he dealt in similar wandering rōnin archetypes as portrayed by Toshiro Mifune for Kurosawa—dishevelled, down on their luck, with nothing to lose except their code of honour and nothing to offer except formidable sword skills.

His impressive debut feature afforded Gosha a rare opportunity to transition from small to big screen and by the time his follow-up, Sword of the Beast (1965) was released, the first two of Leone’s Dollars Trilogy were hugely popular in Japan. Leone’s stylistic innovations and Clint Eastwood’s cool ‘Man With No Name’ impressed him. So, it must’ve pleased Gosha no end to see that The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly (1966), the third in the Dollars Trilogy, drew much inspiration from his own Three Outlaw Samurai and, in turn, he felt justified in borrowing from Leone. Things had come full circle and so-called spaghetti westerns and the new-style chanbara now shared many similarities. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Samurai Wolf saga, which casual viewers will enjoy as pure entertainment, while cineastes will be left with plenty to discuss.

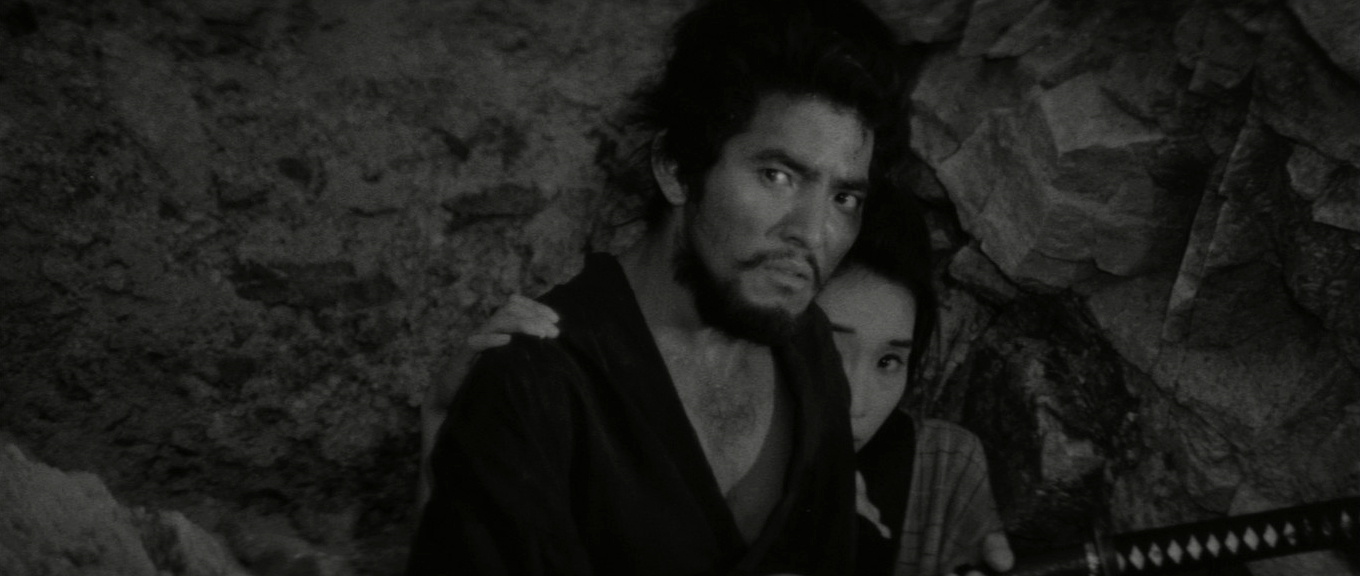

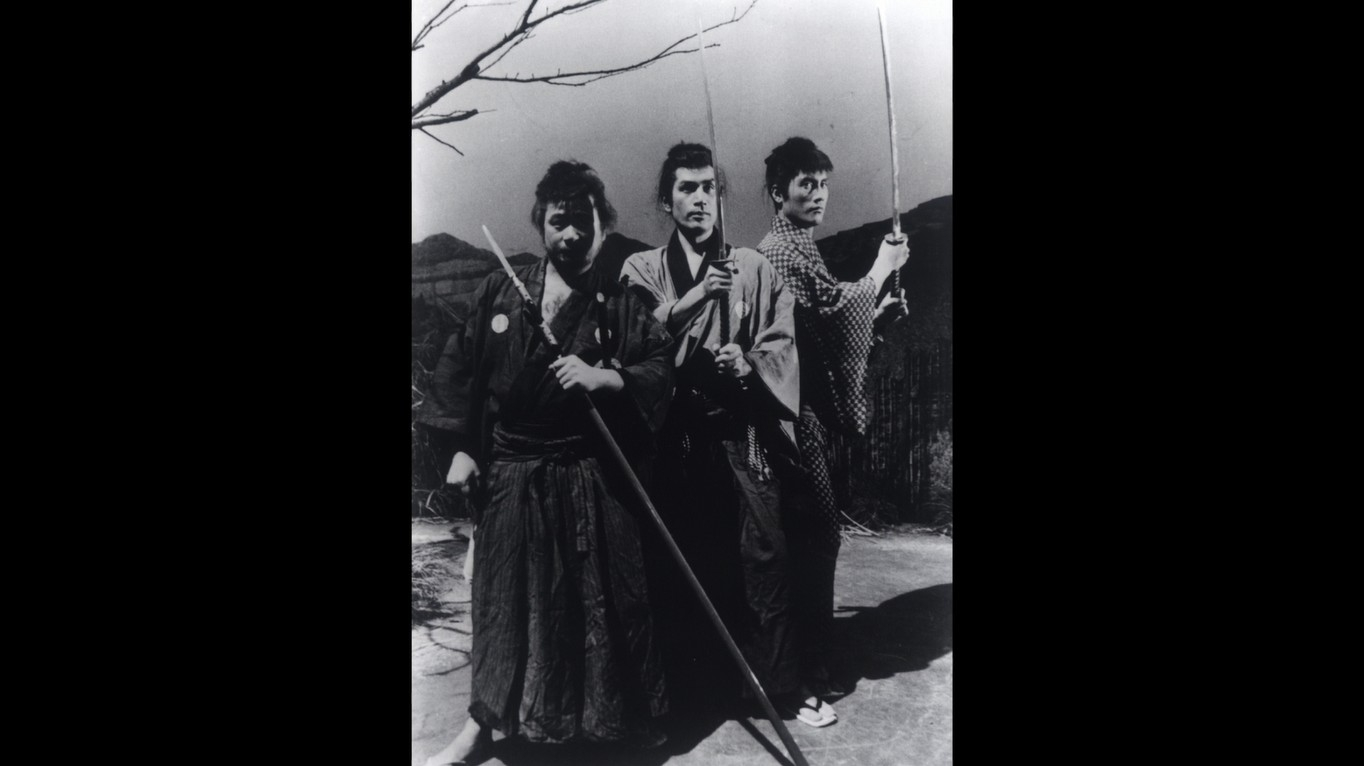

The star of both films, Isao Natsuyagi, was one of a new generation of actors who didn’t come from traditional theatre or kabuki and was fresh out of the Haiyuza Theatre acting school when Toei Studios signed him up. Impressed by Gosha’s Three Outlaw Samurai, they commissioned the director to write and direct a couple of movies that would exploit the genre’s renewed popularity and showcase their new star’s skills. Natsuyagi was young talented and hungry for success and rose to the challenge, delivering a faceted portrayal of a more ‘human’ swordsman guided by his heart, rather than the coldly calculating heroes more common in samurai cinema. He’s just as deadly but nonchalant and only furious when required. Gosha’s two films certainly set him up for stardom and he went on to notch up around 200 appearances on big and small screen in a career spanning six decades.

A charismatic rōnin gets snared into a conflict between officials at a waystation and gains the enmity of a group of thugs.

The action of Samurai Wolf / Kiba Ôkaminosuke takes place in the aftermath of the Tenpō Famine which destabilised Japan during the 1830s. The death toll from starvation and disease meant that many lords lost their peasant workforces and fell on hard times, unable to pay all their retainers and many samurai found themselves masterless, becoming rōnin. We meet Kiba (Isao Natsuyagi) in the process of devouring several bowls of rice which he then admits he has no money to pay for. He’s berated by the proprietor of the inn, an elderly woman, but swiftly assures her that he will work off his debt chopping wood and repairing the roof. She seems more than happy with the arrangement and enjoys watching the young man working hard. Right from the outset, Kiba is established as a lovable rogue with a sense of fairness.

We’re brought into the central narrative when Kiba hears a distant skirmish and rushes to intervene, arriving too late to save a couple of couriers who’ve been ambushed by three bandits. He dutifully takes their bodies to the next town presuming it to be their intended destination. There, we meet the main players in rapid succession. He’s taken in and befriended by Lady Chise (Junko Miyazono), a high-ranking blind woman who runs the relay station that the couriers work for. He has a brief confrontation with the three bandits responsible for their murders who turn out to be henchmen for the corrupt local overseer, Nizaemon (Tatsuo Endô). Their leader (Kyôichi Satô) is a deaf-mute with a trained monkey that sits on his shoulder, acting as a novel assistance animal.

However, their three-to-one stand-off—or four-to-one if we’re counting the monkey—is interrupted by the arrival of some official inspectors but don’t worry, they’ll resume later. Meanwhile, Kiba takes a room at the inn where one of the young courtesans, Oniku (Rumiko Fuji) latches onto him. She’s attracted to his physicality but the brutal house madame, Ohide (Yuki Aresa), disapproves of what she suspects to be ulterior motives as Nizaemon sends for specialist swordsman, Akizuki Sanai (Ryôhei Uchida), to deal decisively with the newcomer.

It’s a big dollop of characters quickly established with broad strokes that all turn out to have more complicated, entwined backstories that finally fit together like a pleasing jigsaw thanks to a highly focussed script by Gosha and regular co-writer, Kei Tasaka. The story turns out to be surprisingly cogent with some clever and unexpected developments as Nizaemon conspires to bankrupt Lady Chise so he can take control of the strategically placed relay station where all travellers on its route must rest their horses, stay, and pay pretty much whatever price is asked for lodging and ‘protection’.

The relay station is honour-bound to insure the value of goods being transported by its couriers, so when a large shipment of gold is coming their way, Nizaemon plans to steal it. The gold would pay his gang and its loss obligate Lady Chise to cover an amount exceeding anything she could afford, forcing her to relinquish control of the outpost. Suspecting this conspiracy, she retains Kiba to help protect the shipment.

The same story could easily be transposed to the Wild West, but Gosha manages to make it his own with some striking set pieces and stylistic innovations. Harking back to his beginnings in radio, the sound design may be the most distinctive aspect as the fight scenes take place in total silence and sometimes in slow motion. The only, quite jarring, sounds are heard when blades ring against blades or cut through a body. This expresses the kill-or-be-killed stakes and the focus of a swordsman, as well as referencing the graphic conventions of manga which had exploded in popularity during the early-1960s.

Visually, he borrows the dynamic deep focus of Leone, with big faces in the foreground and tiny figures in the distance. To this visual grammar he and his cinematographer of choice Sadaji Yoshida, add some distinctive camera work, using top views and low angles through obstructions that work perfectly with the meticulous fight choreography. Apparently, in pursuit of authenticity, Gosha had metal swords made that better matched the weight of a real katana. This meant that the actors had to respect the very real danger of injury while placing their trust in the precision planning of stunt coordinator, Kentarô Yuasa, who’d been working with Gosha since their television days and would become a regular collaborator.

To some extent, Gosha is dealing with the same gendered subtext as the American Western. The masculine heroes revel in dominance to hide their weaknesses through strict adherence to a hierarchical code. In Japan’s patriarchal society of the time, this placed men on a higher rank than women of the same class as them. Though, here, there are some strong female characters bravely challenging the societal codes that bind them, whilst remaining believably within those boundaries. Junko Miyazono stands out as Lady Chise, who’s far from the stereotypical woman in jeopardy one may expect.

The other method of obfuscating weakness is through rigorous martial practice demonstrated by the defeat of other men in combat. Kiba is an anomaly who expresses the Confucian philosophy of respecting others, despite their social rank. Although he’s not a genuine samurai, he respects their code and demands the same in return and, coming from lowly beginnings, also looks out for the vulnerable and socially disadvantaged. A trait that, although perceived as a weakness by his adversaries, turns out to be his enduring strength, ensuring his survival for the sequel…

JAPAN | 1966 | 73 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

Kiba is caught in the intrigue between a crooked goldmine owner, a betrayed swordsman, a manipulative lady, and an arrogant dojo master.

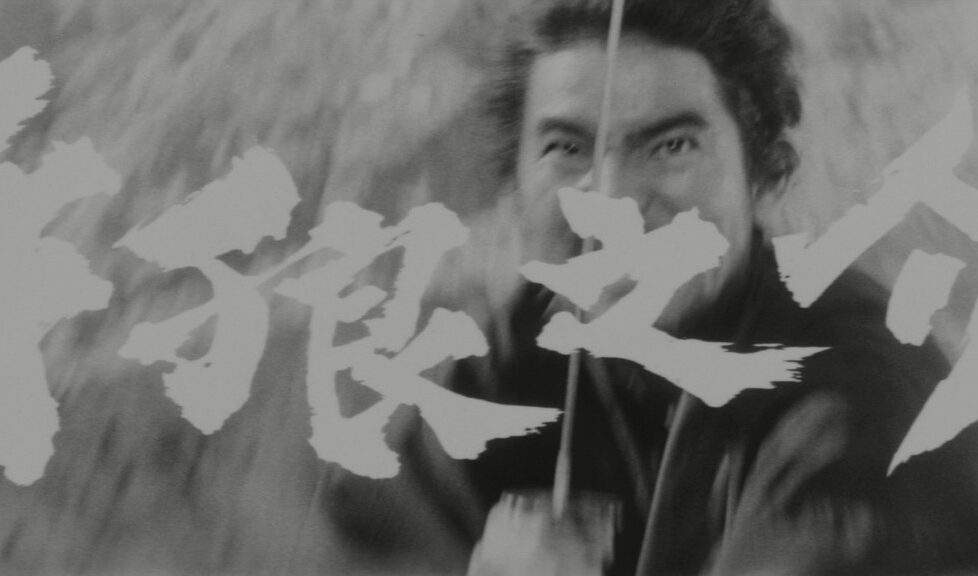

Samurai Wolf II / Kiba Ôkaminosuke: Jigoku Giri—which refers to the ‘hell-slash’ style of decisive sword strike—is more of a continuation than a sequel, though both films have their self-contained narratives. Kiba, the wandering swordsman, is sleeping in a hay loft when he’s awoken by screams of distress and comes to the aid of Oteru (Rumiko Fuji), a young woman being abused by a gang of ruffians. We’ll learn later that she’s the daughter of the boss of a local yakuza clan who has illegally reopened a gold mine thought to be exhausted. This links in with the main drive of the narrative involving an unscrupulous rōnin, Magobe (Kô Nishimura), hired to kill one of the Shogun’s inspectors—who’d discovered the unlicensed mining operation—but was then betrayed by the gang.

Magobe is one of three prisoners on their way to trial and almost certain execution when their armed escort is attacked by men intent on assassinating him to prevent him from giving up the whereabouts of the mine. Kiba intervenes and is then retained to help protect the prisoners from further attacks. The other prisoners are a petty thief and Oren (Yûko Kusunoki), a woman accused of seduction, arson, and murder. Seemingly because Magobe reminds him of his late father, Kiba helps facilitate escape for the prisoners and in return, Magobe offers him partnership in a plan to avenge his betrayers and take the gold fortune still hidden in the mine. The other key player is a dojo master, Ikakku (Ichirô Nakatani) who is brought in to defeat both Kiba and Magobe in some memorable fight scenes, including one in beautifully lit heavy rain and another in a very dark forest at night.

There’s plenty of action and character-driven interactions, but the narrative is far more convoluted than the first film and some sub-plots seem a little superfluous, if not downright confusing. Perhaps the most interesting treatise is concerned with morality and sanity. Oteru is presented as a mad woman but is the most emotionally honest, Magobe is portrayed as sane, but only out for himself and completely pitiless, Ikakku is obsessive, and Oren is deviously manipulative. Again Kiba is positioned as a compassionate man in a ruthless world and his rejection of societal bondage could also be seen as a form of madness in a world where sanity can be a disadvantage. And, again, the entire cast gives worthy performances with Yûko Kusunoki and Rumiko Fuji both shining in their supporting roles.

In the first movie, all the characters were given full backstories that truly underlined their motivations. All, that is, except Kiba. This time around we get his origin story in flashbacks and learn that he isn’t a real rōnin at all, as he was never a samurai. Yet the two genuine rōnin he must face accept his adherence to honour codes and treat him accordingly as one of their ranks. Their ruthlessness and obsessiveness act as a mirror to Kiba’s compassion and quest for selfhood.

This subtext deliberately resonates with the real-life problems faced by a post-war generation who had to seek their own way to gain respect (of self and others) after the age-old traditions had been swept aside with the defeat of Imperial Japan. The young, moral character surviving in the shadow of a corrupt medieval Shogunate can also be read as a metaphor for the young rejecting the corruption of mid-20th-century industrialism and unscrupulous businesses which included chemical companies knowingly flushing toxic waste into rivers that then affected the health of tens of thousands. Having said that, foreign audiences can enjoy both Samurai Wolf movies with little or no understanding of such context or Japanese history, making them far more accessible than many earlier chanbara and period dramas—and a great introduction to the genre.

JAPAN | 1967 | 71 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

director: Hideo Gosha.

writers: Hideo Gosha & Kei Tasaka (Part One) • Hideo Hosga, Kei Tasaka, Norifumi Suzuki & Kiyoko Ôno (Part Two)

starring: Isao Natsuyagi • Ryôhei Uchida, Junko Miyazono, Tatsuo Endô, Kyôichi Satô, Misako Tominaga, Yuki Aresa, Rumiko Fuji (Part One) • Kô Nishimura, Ichirô Nakatani, Bin Amatsu, Yûko Kusunoki, Chiyo Aoi, Rumiko Fuji (Part Two).