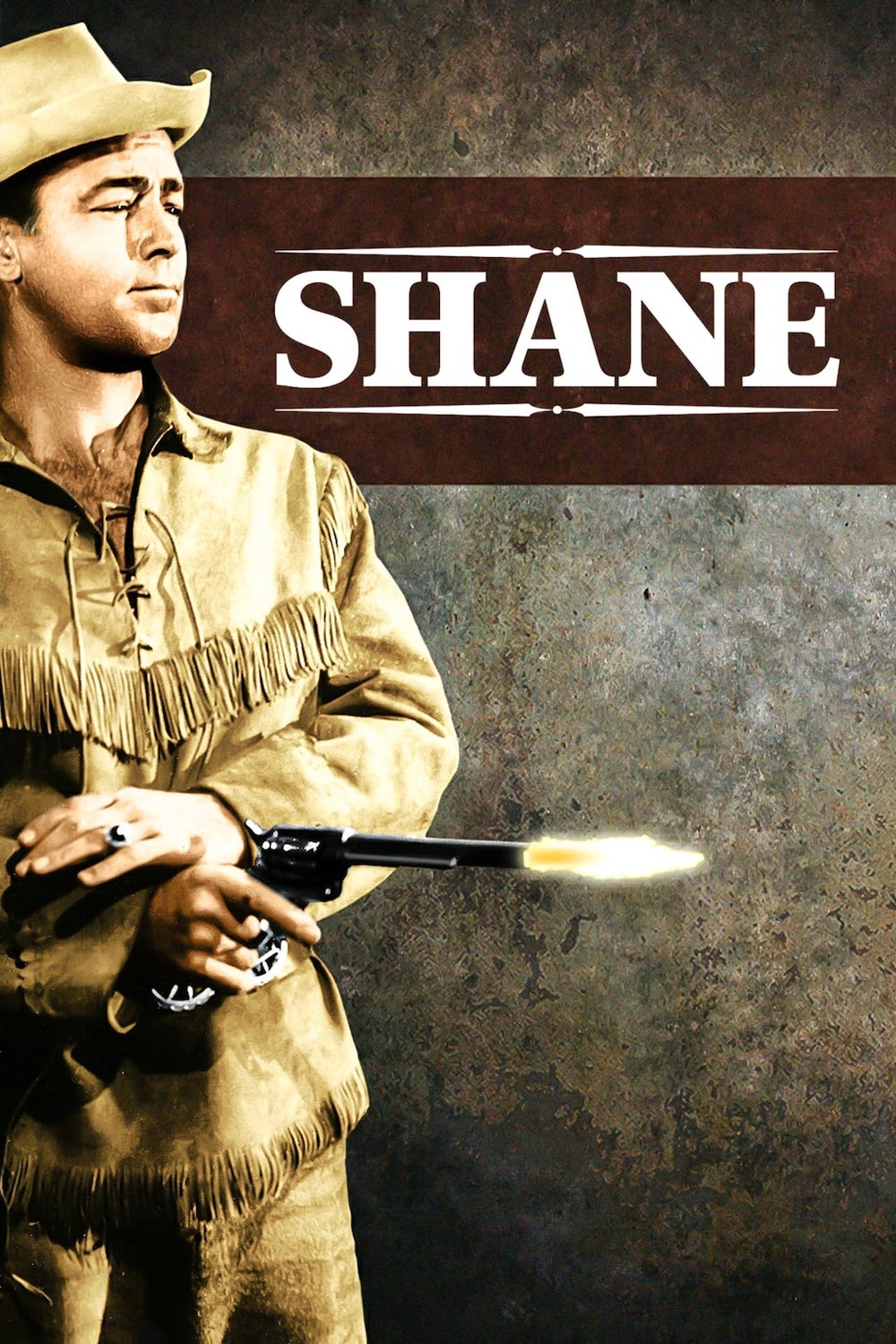

SHANE (1953)

A weary gunfighter in 1880s Wyoming hopes for a quieter life in a new community, until local conflicts force him to act.

A weary gunfighter in 1880s Wyoming hopes for a quieter life in a new community, until local conflicts force him to act.

The 1950s were a pivotal decade for the western, and George Stevens’s Shane has become one of its most celebrated examples—bracketed by two others in the form of High Noon (1952) and The Searchers (1956). Bosley Crowther wrote in The New York Times at the time of Shane’s release: “With High Noon so lately among us, it scarcely seems possible that the screen should so soon again come up with another great Western film.”

It has significant elements in common with those movies, not least the important parts played by boys (though not as important in either of the others as in Shane). All three films, too, mark the way that the makers of westerns, responding in part to competition from TV, were trying to move beyond mere genre and invest their films with greater breadth or profundity of meaning. Often at this point, the new dimension was a kind of mythic heroism rather than the deliberate undermining of the heroic image found in the revisionist Westerns of subsequent decades, but the point was the same.

The French critic André Bazin, identifying these films as “superwesterns” (“sur-westerns”), put it best: where the uncomplicated western tales of the past were characterised by cheerful naivete, he said, “the superwestern is a western that would be ashamed to be just itself and looks for some additional interest to justify its existence—an aesthetic, sociological, moral, psychological, political, or erotic interest, in short some quality extrinsic to the genre and which is supposed to enrich it”. (Bazin didn’t wholly approve of the “superwesterns”, considering that they tended toward “preciousness or cynicism”, but then he disapproved of a lot of things.)

Stevens, like High Noon’s Fred Zinnemann, was not known as a western director—yet another way in which these superwesterns of the ’50s differ from their more prosaic and formulaic predecessors—but his biographer Sinyard calls Shane “quintessential Stevens”, and if we look beneath the genre surface and recognise the extent to which it’s a film about relationships in general, and love specifically, it certainly slots coherently into the director’s output. The relationship between the mysterious ex-gunslinger Shane (Alan Ladd) and the young boy Joey Starrett (Brandon deWilde); the relationship between Shane and the homesteader Joe Starrett (Van Heflin); the relationships between Joe Starrett and his wife Marian (Jean Arthur), between Shane and Marian, between the Starretts and the other local homesteaders—these are the real drivers of the film, much more so than the antagonistic relationship between the homesteaders and the aggressive gang led by the rancher Ryker (Emile Meyer) which might have been the main focus of an earlier western.

The director himself didn’t see it solely in terms of the genre’s development. Shane was “really my war picture”, he said, and though that might well imply that the idea of the homesteader/rancher conflict was central to the film, it also surely means that the movie fits into his emphasis on more serious films after World War II—by that point most notably A Place in the Sun (1951), although after Shane he would then move on to Giant (1956), The Diary of Anne Frank (1959), and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), all of them a long way from the comedies with which Stevens had been associated before the war. Some attribute his new gravity to his wartime experiences in an army film unit, where among other things he covered the Allied liberation of the concentration camp at Dachau.

Certainly, although armed conflict ultimately comes to the fore, for much of Shane it’s more a looming threat in the background. As westerns go, Stevens’s film is notable for its lack of action; there is no violence or sense of imminent, physical threat for a long time, and very little gunplay. Much of the movie has passed before a gun is fired at all, and the whole of the homesteader/rancher conflict—in human terms, Ryker and his gang on one side versus Joe Starrett, the other farmers, and Shane on the other—is largely represented by a single fistfight in a saloon, drawn-out and far from elegant; the final gunfight is over in a few seconds. Great care is taken to show the impact of violence, though, and not to sanitise it (in fact the backwards stagger of Ben Johnson’s Chris at Shane’s first punch seems rather exaggerated); even when Shane is only shooting at a rock for the entertainment of young Joey, Stevens was anxious that the sound of the gunshot should have an effect on the audience.

So, even if Shane might look superficially like a typical good-guys-versus-bad-guys western and the character of Shane himself like the distilled essence of the white-hatted loner, what’s really interesting about the movie, and in the end powerful about it, is the way it differs from this model. And not just in the lack of action; very little in Shane is there just for superficial effect. The care taken by Stevens and his writers, A.B Guthrie Jr. and Jack Sher, is evident. Departures from Jack Schaefer’s 1949 novel seem to add up coherently; the director shot ample footage and took his time editing; the result is an unrushed, frequently almost contemplative film replete with what Bazin called qualities “extrinsic to the genre”.

Its treatment of animals sets it apart, for example. Most westerns are full of horses, and the occasional cow or buffalo might graze or stampede through a few frames, but that’s about it. In Shane, though, animals of several kinds figure a great deal more and not only as part of the scenery but almost as participants. When Shane and Joe Starrett fight, for example, the soundtrack is dominated by the frightened noises of horses and cattle and a dog. In the saloon, when the enforcer Wilson (Jack Palance) hired by Ryker rises from his chair in anticipation of trouble, a dog quickly shifts his position, just as the more timid saloon clientele might have fled in a more typical western.

And if all this is hinting at the potentially Edenic aspects of the west—Starrett describes the valley where it takes place pretty much as a promised land—the setting itself underlines that. The Starretts’ homestead is located in lush terrain between the less friendly mountains of Wyoming’s Teton Range (whence Shane descends from on high like an angel) and the town, just a filthy little cluster of wooden buildings, where the Ryker gang lurk.

Love is another central idea in Shane, where the attraction—one can hardly call it a relationship, because they refuse to let it develop—between Marian and Shane is so well handled, with such honesty, and is so much more than the token “love interest” of earlier westerns, without being overdone. As young Joey says in nearly the final line, pleading for Shane to remain with the Starretts rather than move on, “Pa’s got things for you to do, and mother wants you, I know she does”. But the moment where this is most achingly apparent is one without Shane; he has just left the room and Marian goes to her husband, asking “Joe, hold me. Don’t say anything, just hold me—tight.” She knows that she is in danger of wanting to be with Shane more than she wants to be with her husband, and she needs him to tip the balance back.

Shane opens with the title character riding alone down lush slopes toward what at first looks to be a scrubby dry valley, a typically expansive western orchestral theme by Victor Young playing in the background. We see a young boy—Joey, the son of Joe and Marian—playing at hunting, stalking a drinking deer; it runs at the horseman’s approach, although the irony is it probably has more to fear from Joey than from Shane. Western genre elements soon appear: in almost the first line of the film, Shane comments that “I didn’t expect to find any fences around here”, immediately raising expectations that the movie will like so many others deal with the disagreements between those who want to divide up the land with fences and those who want it left open. Then, when Joey fiddles with his rifle, Shane instinctively goes to draw his pistol, telling us that gunfighting is almost second nature to him. And indeed both these things will turn out to be important in the film, but not quite in the ways the opening might imply.

At the Starrett homestead, where Joey has taken Shane, the gang arrives. Ryker argues with Joe Starrett over rights to the land, though Starrett suggests that Wild West confrontations are no longer valid as a way of life (or death): “The time for gun-blastin’ a man off of his own place is passed,” he says. “They’re building a penitentiary…” And again Shane—while seemingly treading a familiar path—puts a slightly different twist on matters: Ryker is not totally outrageous in his demands, and for all his verbal pugnacity, his first instincts are not toward drawing his six-shooter. The word “reasonable” is used ten times in Shane, almost always referring to Ryker’s position.

He explains that he wants to fence off his cattle to better manage their feeding. Though he says that “when we fight with them [the homesteaders] the air is gonna be filled with gunsmoke”, he actually spends much more time attempting to negotiate than fighting. He tries to hire Shane and later tries to hire Starrett, too, making a generous offer to buy his homestead and pay him a good wage. So Shane is not quite the usual conflict western where implacable bad guys will kill without a second thought to achieve their selfish ends.

Ryker is even given an understandable, if not entirely logical, basis for his position. He and his kind were there first, before Starrett and the homesteaders, people “who never had to rawhide it through the old days”. “We made this country,” he says (needless to add, no mention is made of Native Americans in this context).

And Starrett’s response is equally unusual: he doesn’t, as you might expect, argue that the valley is for the law-abiding, but that it is for families, an interesting distinction. Not only does this contrast him and his family with the Ryker gang (who seem to have no women or children, and indeed no homes—perhaps they live in the saloon) but it also contrasts the Starretts with Shane himself. After all, he does not have a family either, and one of the underlying tensions in the film is the question—unresolved until the end—-of whether he will become a permanent honorary member of the Starrett family, or remain a stranger passing through; perhaps, indeed, one who like Ryker also belongs a less law-abiding past.

In any case, Shane remains on the Starrett side of the argument for now. He and Joe Starrett uproot a tree stump that has been defeating the father, signalling the difference that Shane’s arrival might make: Joe has been stubbornly working on it without success, and Shane makes the difference. But even this relationship does not pan out exactly how you might expect. Similarly, the homesteaders’ 4th of July celebrations at first seem a jolly, down-home interlude, serving the same function as the almost random musical numbers sometimes inserted into earlier westerns. But later we realise that their bigger structural purpose was to contrast with a funeral; “Abide With Me” is played at both events, but between the festivities and the mourning a line has been crossed in the homesteader-Ryker dispute, and it’s only after the funeral that Shane, at last, becomes a man of action, urging resistance.

Meanwhile, through all of this, young Joey Starrett’s idolisation of Shane provides a counterpoint (Schaefer’s novel is told from Joey’s point of view). Joey even ends up wearing near-identical clothes. But he has a very set idea of what Shane ought to be like, different from Shane’s own and certainly not compatible with his father’s conviction that “the time for gun-blastin’” is over. Though Shane initially wears no hat and no gun, when he does pick up a firearm Joey opines that it “goes with him”; he wants Shane to be aggressive; while Shane insists that “a gun is a tool… a gun’s as good or as bad as the man using it” (a line the National Rifle Association must love), Joey clearly believes that the gun makes the man. In one of the movie’s most effective scenes, he gets carried away shouting “bang! bang! bang!” until his mother can bear it no longer.

Narrative and themes apart, one of the first things to stand out in Shane to modern eyes is the exaggerated, heavily saturated Technicolor so typical of the time. Indeed, though it was filmed on location in Wyoming and is presented in a widescreen format, this (and the soft focus sometimes used for Marian) can have the peculiar effect of making it feel like a studio-shot exercise in visual unrealism. But Shane also gains a great deal of impact from other filmmaking decisions by Stevens and his team, even if they are not quite so immediately obvious.

It is, in visual terms, very fast-moving for a western of the time; the average shot length, according to the Cinemetrics database, is only 4.9 seconds (compared with almost 10 for The Searchers, 6.8 for 1950’s Broken Arrow, and 7.8 for 1953’s The Naked Spur, for example). It has been suggested that Stevens took this route because he found it challenging to handle movement within a single shot, but whatever the reason, it works. In fact, it may well be this comparative hyperactivity that allows Shane to move fairly slowly in plot terms without coming across as draggy, and to give a persistent impression that something is happening, even when the actual on-screen action seems mundane.

The compositions by Stevens and cinematographer Loyal Griggs are also striking—Crowther thought the film had “the quality of a fine album of paintings of the frontier”—and especially those involving people: they make clear that Shane is never quite one of the homesteader group, for example.

This is most impressive, perhaps, in the key scene where Palance’s Wilson confronts the homesteader Torrey, nicknamed Stonewall for his Southern affiliation during the Civil War and played by Elisha Cook Jr. Wilson is higher up than Torrey, standing on the boardwalk while the latter is at a disadvantage down in the muddy street, and already we can tell that Wilson is likely to have the upper hand metaphorically as well; then as Wilson moves to a higher level still it becomes clear that Torrey has in fact walked into a trap, a psychological as much as a physical one (Wilson will taunt him into a fight he cannot win). Shortly afterwards, when the homesteader Shipstead (Douglas Spencer) returns with Torrey’s body—and a horse seemingly reluctant to carry it—the slow pan across a waiting family group (dog in the centre) makes it clear that the violence just erupted in the valley does not only threaten the menfolk.

All these characters are secondary, and a strength of Shane is that even the more minor people are so well sketched. Shipstead and his wife (Edith Evanson) are to some extent the comedy Scandinavians familiar from other westerns, but the film treats them with respect too, and though Torrey also has his comic side he is one of the most sympathetic individuals; we can readily believe how the combination of his small stature and the constant teasing he receives over the Confederacy’s defeat has made him so prickly. Among the other secondary roles, Palance (billed here as Walter Jack Palance; it was only his fourth film, only a couple of years later than his memorable debut in Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets) is chillingly calm, quiet and self-assured, while Paul McVey is convincing as the saloon owner Grafton: a responsible man, middle-aged and non-violent but not weak—perhaps what Shane himself might aspire to be if he could ever shake off the gunsmoke of his own past.

Heflin as Joe Starrett, though in some ways less developed than Marian and Shane, is at least equally interesting and his actions in the final act raise nagging questions. Is he just “doing the right thing” in standing up to Ryker? Or is his bigger motivation that he thinks he needs to prove his courage is equal to Shane’s, given his son’s and even his wife’s adulation of the newcomer? Or does he, just possibly, actually want to die at the hands of the Ryker gang and leave them with Shane, convinced (or disheartened enough to believe) that Shane would be the better husband and father?

Heflin does a great job of conveying the doubts and determinations of man who can’t, or at any rate won’t, overtly express them. That applies to Arthur’s Marian as well, and (as often with Stevens, though less often in earlier westerns) she is every bit as important as the men; in her case, though, the problem is not so much a lack of self-awareness as too much. Again, as with Heflin’s Joe, Arthur in her last feature film captures the character’s dilemma poignantly.

Such inhibitions about self-expression certainly don’t affect the boy Joey, and deWilde—only just past his eleventh birthday when the movie was released—is an unforgettable character, not strictly involved in the main plot at all yet absolutely essential in expressing the mythology (or what would become the mythology) of the west, making us wonder whether Shane is being forced to play a role he doesn’t really want to, making us appreciate that Joe Starrett’s less glamorous approach to life is in the long term more worthwhile. DeWilde, who continued acting until he died in a road accident shortly after his 30th birthday, was the youngest person ever nominated for an Academy Award, for his role in Shane.

The child star was described later as “small for his age and a bit too pretty” to be taken seriously as an adult performer, and the adjectives could easily be applied also to Alan Ladd. A well-established actor who had for a long time been more associated with drama, crime and noir and had only recently started starring in westerns, he was not the first choice for the part of Shane but was an inspired one: at around 5’5″, with slightly bouffant blond hair, his distance from the physically imposing square-jawed stereotype makes his potential for violence instantly intriguing.

Stevens then adds to the contradictions by repeatedly filming him almost as if he were Jesus; his self-sacrifice on behalf of the homesteaders, when a fight turns against him and the Ryker gang beat him up, only reinforces this air of saintliness and near unreality. We never feel we truly know Shane in the way we do the Starretts or indeed Ryker, and the question lingers as to whether the entire film’s presentation of him is a reflection of Joey’s hero-worship rather than the “truth” in the fictional world. The boy repeats the man’s name over and over again throughout the movie, like an incantation. Shane finally twirls his gun at the end; is he doing it for himself, for Joey, or for us?

Indeed, though the Shane of the novel is more obviously dark, there is an extent to which the character in the film is a canvas on which other people and the situation itself can express their own meanings; Philip French wrote that “perhaps no other actor could have given the character quite that quality of blank, ethereal detachment which Ladd brought to the part. He is like an angel in an otherwise realistic medieval painting, and sets off the earthy realism of Van Heflin’s father, Jean Arthur’s unfulfilled pioneer mother and Brandon deWilde’s deprived, yearning child.”

Shane was Ladd’s biggest hit to date and a major critical success too; Griggs won an Academy Award for his cinematography and Stevens, Palance and screenwriter Guthrie were all nominated, as well as deWilde. Its reputation has only grown in recent decades, and although there have always been dissenters (Pauline Kael thought it “sluggish”), if anything it has become so celebrated that even those few elements which don’t work so well have gained in reflected glory: Young’s score, for example. The main theme is strong in a conventional way, musical comfort food, but for the most part, the music is excessive and the composer is rather too fond of a descending three-note “sinister” motif and other commonplace material. Stevens actually used part of Franz Waxman’s score for Rope and Sand (1949) for the scene where Shane rides into the town, suggesting he wasn’t wholly satisfied with Young’s work, and the most effective music in the whole film is the simple performance of Dixie and Taps on the harmonica in the funeral episode (after which Young promptly comes in over-strongly again).

This is a minor shortcoming, though. And if Shane probably does not seem as original now as it might have in 1953, that is because it and particularly the title character himself influenced so many westerns that came in between, from Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) to Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) and Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider (1985). John Frankenheimer was a big fan; so is Woody Allen, who cherishes its portrayal of relationships.

Shane may not seem the obvious inspiration for the director of desperately sophisticated urban relationships movies like Interiors (1978) and Manhattan (1979). But then like Shane himself, the archetypal western man of mystery, Stevens’s beautifully crafted, multi-layered, exploration of the relationships underpinning a small incident in a small Wyoming settlement in the 1880s is not quite what it seems when you first meet it.

USA | 1953 | 118 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: George Stevens.

writer: A.B. Guthrie Jr. & Jack Sher (based on the novel by Jack Schaefer).

starring: Alan Ladd, Jean Arthur, Van Heflin, Brandon deWilde, Jack Palance & Ben Johnson.