HUSBANDS (1970)

After the death of a common friend, three married men leave their lives together, seeking pleasure and freedom and ultimately leaving for London.

After the death of a common friend, three married men leave their lives together, seeking pleasure and freedom and ultimately leaving for London.

When author John Updike was asked to explain the ideas behind his 1960 novel Rabbit, Run, he was upfront about it being a reactionary effort. “It was meant to be a realistic demonstration of what happens when a young American family man goes on the road,” said Updike. “The people left behind get hurt.” It’s not a book disgusted by the search for personal freedom, but it is one critical of the coldness and egocentrism of the middle-class men who put their anxieties before all else.

We don’t need to look far to find the cinematic equivalent of this notion. John Cassavetes’ ‘comedy’ Husband is a bitterly truthful reaction to a cinema that glorified men and their supposedly noble aspirations. The all-American cowboys and lawmen that populated the cinema of the 1950s and 1960s were slowly brought into focus as the ’60s went on, and a new breed of cinematic hero questioned it. Dennis Hopper’s iconic Easy Rider (1969) presented an anti-hero type for the new age, but some filmmakers decided to do away with the notion of heroes, anti-heroes, or even villains.

Instead, here were films illustrating a vicious truth about the average American male. They weren’t heroic, anti-heroic, notably villainous, or any of the grander ideas films can impose upon people. They were real and appalling in a manner that doesn’t fit in with a traditional cinematic notion of archetypes. Their behaviour and choices (or lack thereof) were much more in keeping with the actions of actual people. What emerges in Husbands is a portrait far more disturbing and uncomfortable than anticipated, because it’s all so recognisable.

Husbands focuses on a trio of middle-aged friends—Gus (writer-director John Cassavetes), Harry (Ben Gazzara), and Archie (Peter Falk)—as they drink, bully, fight and puke their way through the mourning process after the death of their friend. The first scene is a photo montage of the four (soon to be three) friends by the poolside; drinking beers and eating hotdogs with happy-looking families and a propulsive jazz track playing.

They could be any men in suburban America. They probably set off fireworks on the fourth of July, and have people over to watch the Superbowl. But photos are only representations of reality; a manufactured object that show a truth that the viewer wishes to see. We see what we expect to see.

When Cassavetes shows us the men in action, those images are shattered. Instead of a playful quartet of joyful but dependable patriarchs (the kind cinema had previously and subsequently portrayed), what we find is a three-legged dog; a trio of damaged and poisonous people, limping along and seemingly begging o be put out of their miseries. Cassavetes watches the trio as they awkwardly make their way through a crowd of mourners at the funeral of their late friend. The takes are long and capture their fumbles and apologies, shot through a telephoto lens that both situates the men in a location and reveals just how incongruous they are.

“People get symbolic over death. They get very formal, and it’s really ridiculous because it’s probably the most humiliating thing in the world,” says Archie. He and his friends are shooting themselves in the foot; they think everything is bullshit, yet they go along with it anyway. They have no alternative, besides utter self-destruction. There’s no process to grieve that deals with its complexities, nor any way forward that acknowledges what a farce their lives are. This is what positions Husbands as such a fascinating exercise: it presents the reckless behaviour that people use to cope, but it refuses to admonish them… because it has no answers as to how things should be done.

The trajectory of the film is circular. During long, drunken scenes, we might learn a little bit more about each of the men, yet they get nowhere, arriving at no conclusions, not anywhere close to breakthroughs. That’s because they’re not looking for them. The self-realisations that films about grief often centralise are imploded here. This isn’t a journey of self-discovery, it’s a farewell tour of self-annihilation.

In one of the film’s many prolonged scenes, the husbands sit around drinking with fellow mourners, each taking turns to sing a song. As it progresses, the men get increasingly drunken and belligerent, shouting insults, forcing kisses onto women, while Archie gets undressed. Husbands is a film of discomfort. At the funeral, it’s the men who are uncomfortable… but, during scenes such as these, audiences are made to sit in passive discomfort, made all the more intolerable by the men’s enjoyment of it all. They roar with laughter, they do ‘voices’ and acts… nobody outside of their threesome exists.

In the hands of a lesser director, situations like these might only superficially glance at what’s happening with these men. But Cassavetes is confident that the longer we sit with the husbands, the more will be revealed to us. It has the effect of taking part in a real-life conversation with someone who doesn’t quite realise how much of themselves they’re exposing. It’s only by sitting with this prolonged discomfort that we begin to see the ugly truths of these men.

Cassavetes’ style has often been described as improvisational, but this applies to him as a director, not as a writer. By accounts of actors who worked with him, the dialogue was always specific, but the actions were not. This achieves the remarkable effect of feeling both profound and totally ordinary; a precursor to independent film before it was an established market in the US.

The looseness afforded by this approach frees up the actors to present their characters as nakedly as they wish. At points, the men seem to be a three-headed monster, not so much with individual personalities but instead a collective Id. The actors play off each other with shockingly realistic chemistry, a truly naturalistic friendship bound by something unsaid but electric…. because what are friendships ever bound by? History? Location? Gender?

For some time, the husbands aimlessly drift through the typical male-bonding exercises that are supposed to build team spirit and brotherhood. They play basketball and go swimming, they play-fight in the middle of Manhattan streets; three middle-aged men dressed in suits behaving like children, playing out the absurdities of their lives. As an even more absurd and alternative comedy take on this, it’s hard not to wonder if the comedy trio ‘Stella’ consisting of Michael Showalter, Michael Ian Black, and David Wain were inspired by Husbands.

None of these activities appeals quite as much as drinking, and that’s mostly what the husbands get up to. Their decisions are reactive and impulsive. They’re not following ideals, they’re doing whatever they can to make their unhappiness end or for everyone else to feel as lousy as they do. They end up in London, a destination arbitrarily chosen by Harry after he attacks his wife and walks out on his job. But London doesn’t end up being too different from New York. The men go gambling, where they play up their Yankie charms to English women who, perhaps tricked by their international allure, can’t quite see the ugliness in front of them.

The men cheat on their wives after bringing the women back to a hotel room. The interactions between them are confrontational, cruel and deeply uncomfortable. Mary (Jenny Runacre) is at the receiving end of Gus’s endless harassments which he tries to frame as ‘playful’. Meanwhile, Archie verbally attacks Julie (Noelle Kao) for kissing him back when he kisses her. Mary ends up telling Gus she hates American men (“you’re always smacking people on the back and calling each other pal”), while Julie would rather wander out into the pouring early morning rain than spend more time with Archie.

It’s the point at which Husbands highlights just how intolerable the husbands are, and what an utter misery it is to be around them. They’re a perpetual-motion machine, spurring each other on and fuelled by each other’s laughter. “Like I’ve been telling my wife for years,” says Harry, “aside from sex, and she’s very good at it, goddamn it, I like you guys better.” Perhaps this is the case because people will always value their enablers over their victims. Their friendship is a close and ugly vessel that each of the three men can dump their sadness and anger into, without really dealing with it. When they’ve purged, they wander home with gifts for the kids and sheepish ‘honey, I’m home’ smiles.

When Gus’s son calls into the house for his mother to come out because dad’s home, she never emerges. For all intents and purposes, she doesn’t exist to Gus. None of the wives to these husbands do. Nor the children. They only exist in the form of guilt. What kind of ego does it take to disappear across the sea for a week and return with a bag full of airport-bought gifts, and expect your wife to run out and hug you, and for your child to do anything but cry? If Husbands is a comedy, then it’s a comedy of the absurd and the pathetic.

Later comedies would turn the sharpness of Husbands into something cuter and digestible with the emergence of the ‘bromance’ subgenre. It would gently mock, then coddle, the American man-children (Judd Apatow is on the record as a huge fan of Husbands) that Cassavetes’ film eviscerated.

The title ‘Husbands’ implies a generality that says, yes, these are any and all husbands. If that’s the case then the film is even bleaker than it first appears, suggesting a spiritually bankrupt and broken nation of people—self-appointed as leaders, bread-winners, pillars of communities, lawmen, cowboys, fathers and husbands—lost in self-imposed roles and given permission to express their misery. It’s ugly to look at, but it’s a truth that few filmmakers would be bold enough to exhibit. Husbands, in the very best and most necessary way, is a mess.

USA | 1970 | 142 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

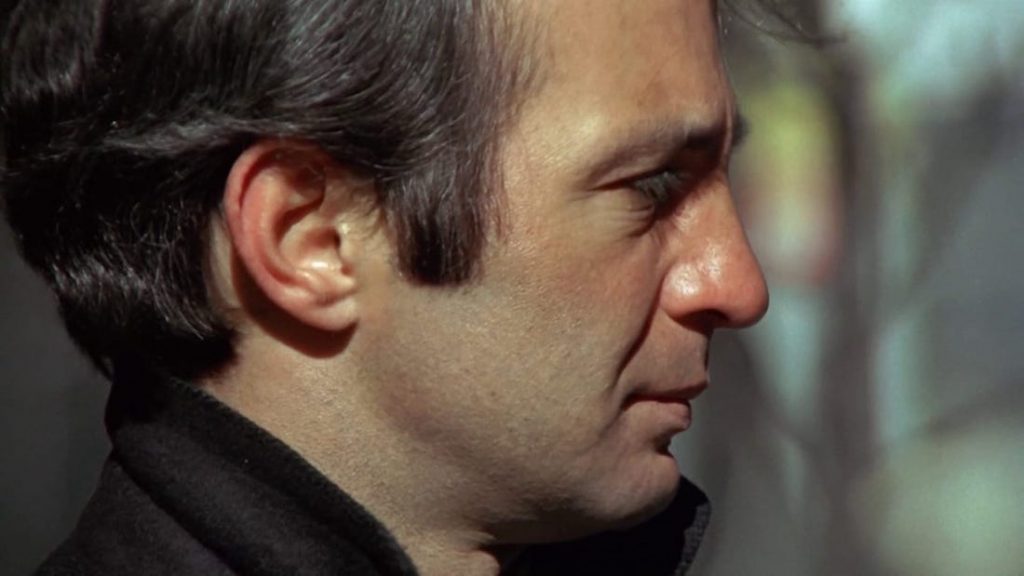

Criterion’s release of the film is impeccable. The transfer is beautifully handled, with colours reproduced realistically. But most essential is that the cleanup doesn’t remove the grit and texture of the original film. Much of Husbands is supposed to look grotty, and that is presented in this release faithfully. The scenes set on the rainy streets of London are particularly engaging, while closeups of the actors look sharp and beautifully detailed. The audio remaster is also fairly clear, with the few jazz needle-drops sounding particularly great.

writer & director: John Cassavetes.

starring: Ben Gazzara, Peter Falk, John Cassavetes, Jenny Runacre, Jenny Lee-Wright & Noelle Kao.