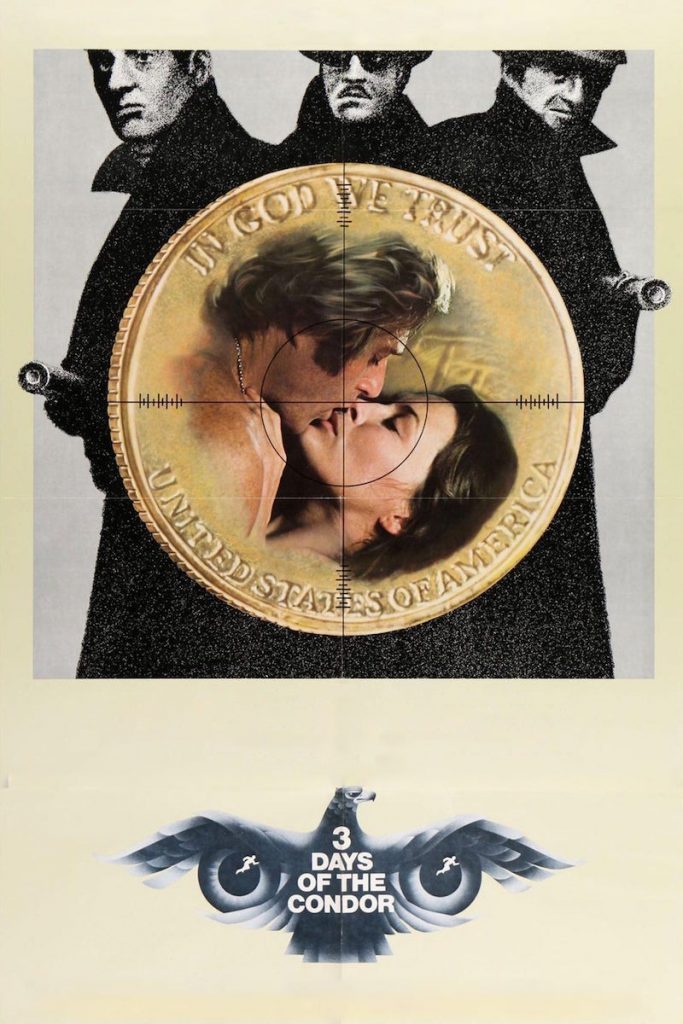

THREE DAYS OF THE CONDOR (1975)

A bookish CIA researcher finds all his co-workers dead and must outwit those responsible until he figures out who he can really trust.

A bookish CIA researcher finds all his co-workers dead and must outwit those responsible until he figures out who he can really trust.

In 1974, James Grady released his novel Six Days of the Condor. It was a taut political thriller about an ordinary office worker Joe Turner (Robert Redford), codename Condor, with the inconspicuous job of reading mystery books and sending off tips and tricks to the CIA. Then, one day, he returns from lunch to find his colleagues massacred, so must apply the skills he’s only read about when the agency itself tries to assassinate him next.

The book was 192 pages of suspense and espionage, adapted by Sydney Pollack the following year as Three Days of the Condor. But a far more interesting and true to life book was being written at the same time, whose contents got teased when leaked to The New York Times in 1974. The ‘Family Jewels’ documents compiled illicit and illegal activities committed by the CIA, recorded by the CIA, to keep track of all their corruption post-Watergate. Compared to the svelte Condor, this was 693 pages of “skeletons”, released many years later in 2007.

Mark Twain once said “truth is stranger than fiction” which led to the underperformances of both Breakout and The Killer Elite in 1975 (both featuring the CIA as an enemy), as once fantastical paranoia pieces became familiar stories in the current culture. But while Peckinpah released a dud with Elite, Pollack delivered another powerhouse thriller with an all-star cast. The director himself is a 48 time Academy Award nominee, with 11 wins, and that talent shines through in Three Days of the Condor.

The style is wholly 1970s with a wonderful contrast of high-tech government technology scored to the Lalo Shiffrin-esque music of Dave Grusin. A standout sequence highlights this involving some wiretapping wizardry with a stolen phone line-tester and some recorded dial tone frequencies—although, at this point, I realised almost every surveillance trick in the movie involves people making phone calls.

For a story told often through telephones, five-time Oscar nominee Owen Roizman captures the wintery themes of isolation and paranoia through his cinematography, bolstered by Pollack’s confidence in long and unflinching takes. There’s a moment admiring art depicting “not quite autumn, not quite winter… feels like November” which transcribes the mood of Condor, between the almost snug and cosy interiors and its cold and vulnerable ventures out into the city.

What was the weather like in Norwood, Massachusetts, back in 1976, when Aleksandras Lileikis moved there to work for the CIA? This was after his immigration status got challenged for “known Nazi sympathies”, but the CIA hired him anyway up until 1996 when he got charged with genocide in Lithuania for his involvement in World War II death squads. He was one of “at least a thousand” Nazis brought into the country to work for the CIA.

Their misunderstanding of one man is the same with Turner, who appears the opposite of Hollywood’s representation of a CIA man. Unlike Jack Ryan, Pollack introduces him bicycling in the midst of heavy traffic at odds with the world around him but weaving through the established grind. Redford’s natural charm shines even when threatening the government and does well to represent the majority of ordinary Americans serving a system corrupted by a few higher-ups. He likes Dick Tracy comics, ignores stifling protocols, and when reporting the massacre he almost can’t recall his colleague’s codenames.

Freelance assassin Joubert (Max Von Sydow) judges his target “lost, unpredictable, even sentimental. He could fool a professional, not deliberately”, and despite Turner’s best efforts the world around him constantly calls him Condor when he wishes to be simply Joe Turner.

In the same year, the CIA initiated ‘Operation Condor’, which played out the international conspiracy of political repression and state terror Turner threatened to expose as Condor. A declassified FBI report detailed several levels of implementing right-wing dictatorships across South America; mutual conspiring with military intelligence agencies of surveillance, abductions and disappearances of dissidents, and a rotating cross-border league of assassins to remove “subversive enemies”. Deaths attributed to Condor are disputed, though some estimates are shocking—like the ‘Archives of Terror’ listing 50,000 dead, 30,000 disappeared, and 400,000 imprisoned.

One of the CIA agents in Condor argues all governments “play games” and some take those games too seriously, but that the innocuous work Turner did for them are necessary precautions in case other countries play out their own games first. The argument is made on whether the American public deserves to know what’s being played. Though this is left as food for thought rather than explored discussion as Condor focuses more on a relationship of trust between Redford and Faye Dunaway.

Some other complicated issues are the sexual politics explored in Condor with Kathy Hale (Dunaway); a stranger ‘kidnapped’ by Turner desperate for a hideout nobody would think to search. While sceptical, she comes to believe him and share his newfound confidence aiding in his counter-espionage against the men hunting him. Dunaway is an equal star among Redford and Sydow but the Stockholm Syndrome subplot feels especially rushed opposite the played out thriller aspects. Redford seems less charming in their shared scenes given that he’s always tying her up and questioning her relationship status.

The aforementioned scene of her “lonely” photography asserts a strange and uncomfortable assumption that all women are waiting for some man to bring adventure into their otherwise boring lives. Clumsily cross-cutting between a love scene and her photos to insinuate being taken hostage is the best thing to happen in her life. It reminds me of the incredibly unearned romantic subplot in an otherwise fantastic Blade Runner (1982), in which pulp detective males discover they can’t trust anyone except the woman whose simple, surface emotions are easy to read a lack of any underlying motive in them. Also, the film opens with an existing love interest who gets murdered so Turner’s moved on within three days. A disappointing and distracting emotional middle act in a tight political thriller.

A woman far more independent in her own actions was Gina Haspel, the CIA’s first female and current director—who not only oversaw the secret Thailand prison, Cat’s Eye, which utilised newly-developed ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’ in the hunt for Bin Laden (see Zero Dark Thirty for more girl-boss action) but further advocated for the destruction of video evidence of said techniques that could’ve been “devastating to the CIA”. It was torture.

The violence in Condor is shocking, if brief, but I hesitate to describe the inciting catalyst as Pollack’s unflinching direction is better seen than described. In general, the balance is well-handled by screenwriters Lorenzo Semple Jr. (Parallax View, Flash Gordon) and David Rayfiel (a ten-time Pollack collaborator). The emphasis lies far heavier on the possibility of violence rather than protracted action, and I’m sure without watching that the 2018 TV adaptation, titled Condor, injects some modern-day adrenaline.

That said, anyone expecting a juicy conspiracy will be let down, as Turner’s personal journey takes focus, whereas the CIA plot is a McGuffin explained rather boringly at the very end. Ending on an ominous note aids in the staying power of the story; Turner threatens to expose all their secrets in The New York Times only for the CIA to shake his trust in even the free press. Unlike Bourne-style thrillers in which the hero foils a scheme and one-ups the shady governments, Condor ends with Turner learning a truth that will haunt him for the rest of his life.

Now, the biggest criticism of Three Days of the Condor and many Hollywood ‘takedowns’ of the government is the revelation of a “CIA within the CIA”, as people keep forgetting that the point of ‘a few bad apples’ is that they ‘spoil the orchard’. Joubert’s assessment on Turner’s sentimentality comes true who mourns “I was born in the United States, I miss it when I’m away too long” because even when a country is trying to kill him, he remembers the good times. At the time it got criticised as political propaganda, such ideas of evil conclaves being a way to minimise responsibility, Pollack himself “intended it always a movie.”

I’m reminded of Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), an obvious homage to Condor in casting Redford in an antagonistic role as part of the insidious HYDRA infiltrating SHIELD. In contrast to Condor’s contemplative conclusion, Winter Soldier ends with the cinematic destruction of colossal government airships that provide Big Brother oversight with a massive loaded gun at every possible threat. When the former Nazi organisation gets revealed, they must be stopped! But SHIELD leader Nick Fury introduces the whole concept to the superhero Captain earlier on, and when America is in charge of such monstrous potential all we can do is tut in disapproval.

I pepper this retrospective with declassified, public information on the CIA because Condor questions if The New York Times would publish such material when they did at the time of release, and every time this story repeats itself we all tut in disapproval.

USA | 1975 | 117 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • FRENCH

director: Sydney Pollack.

writers: Lorenzo Semple Jr. & David Rayfiel (based on ‘Six Days of the Condor’ by James Grady).

starring: Robert Redford, Faye Dunaway, Cliff Robertson, Max von Sydow John Houseman, Addison Powell & Tina Chen.