REBEL MOON – PART ONE: A CHILD OF FIRE (2023)

When a peaceful settlement on the edge of a distant moon is threatened by a tyrannical force, a mysterious stranger becomes their best hope for survival.

When a peaceful settlement on the edge of a distant moon is threatened by a tyrannical force, a mysterious stranger becomes their best hope for survival.

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away… Zack Snyder didn’t rip off Star Wars (1977) to make his magnum opus Rebel Moon. Of course, that isn’t a fair imputation. After all, Star Wars itself borrowed heavily from Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954), and its iconic tropes echo a hundred different film serials like Flash Gordon. Derivation isn’t a sin, not as long as your own voice resonates through the borrowed beats. As the Bard himself, William Shakespeare, could attest, many of his plays drew on recycled plots and characters from the same creative well that now-forgotten writers shared. It’s only when the voice behind the familiar elements falters, lacking both spark and originality, that a story truly earns the derivative label.

Enter Rebel Moon – Part One: A Child of Fire.

This new space opera focuses on the eponymous child Kora (Sofia Boutella), an ex-soldier living on a farming moon. Her peace is shattered when the cleverly named King’s Gaze, an imperial warship seeking revolutionaries in the wake of the royal family’s assassination, arrives from the Motherworld to demand grain for its troops.

(The genre’s medievalist roots clash with its sci-fi trappings here. Why would an interplanetary government boasting gigantic warships and space stations, brimming with futuristic technology that would appear magical to us, rely on bushels of grain to feed its troops? It’s a well-known saying that an army marches on its stomach, but if a present-day pauper can order pizza from their phone, surely future generals could provide more than basic grain rations. Despite this familiar trope, the screenplay could have had the bad guys bartering for a unique type of ale or some rare element, adding a touch of believability and intrigue to their motivations.)

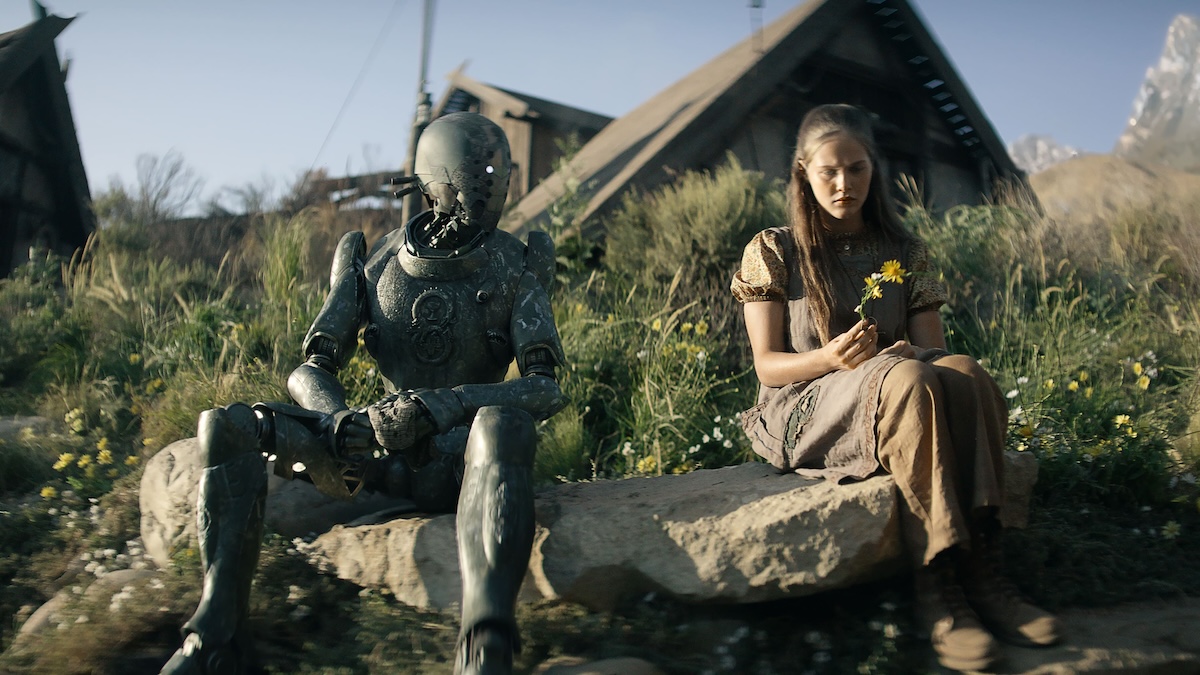

Initially hesitant to confront Atticus Noble (Ed Skrein) and his imperial forces, Kora’s resolve hardens when forced to kill a team of soldiers. Fueled by anger and a thirst for justice, she embarks on a galactic odyssey with her fellow farmer Gunnar (Michiel Huisman) to assemble a rebel force. Their ragtag crew is comprised of seasoned ex-general Titus (Djimon Hounsou), the enigmatic cyborg swordswoman Nemesis (Doona Bae), the ferocious warrior Darrian Bloodaxe (Ray Fisher), and the charismatic mercenary starship pilot Kai (Charlie Hunnam). Meanwhile, Anthony Hopkins lends his voice to a whimsical C-3PO-esque creature dispensing lore, while Cary Elwes appears in flashbacks as the fallen king whose legacy inspires the rebellion.

None of the acting performances are remarkable, though that’s not entirely the actors’ fault. Anthony Hopkins, perhaps, stands out with his dignified tones. Kora also has a more coherent backstory and motivation than Rey from the Star Wars sequels (2015-19). However, her deliberately iconic outfit and poses seem to be all the filmmakers care about. Hunnam delivers a somewhat convincing rogue, an archetype he appears to have mastered, while Skrein twirls a moustache with practised ease, a role he’s inhabited before.

At his core, Zack Snyder remains a comic-book writer. His character and scene ideas spring from pop iconography, their essence rooted in stylisation rather than deeper psychological motivation or themes.

What ultimately frustrates me about Rebel Moon and other Snyder films is that they, at times, flirt with genuine depth. For instance, Kora’s recollections of the royal family hint at a missed opportunity—-how the king leaned on his daughter’s compassion as a future leader could have explored the complexity of legacy and responsibility. Similarly, the film’s undercurrent of colonialism had the potential to blossom into a truly powerful commentary.

Snyder solely fixates on the surfaces of things, never delving deeper than surface appearances. His mode is juvenile; he confuses gritty darkness for complexity, mistaking jadedness and sadomasochism for mature character development and thematic depth

The trope of rape in fantasy fiction has sparked extensive debate, with a broad consensus forming: if the story can be told without it, then it should be. The rule arguably tends to ensure that rape is only used as an element when the story is about it, and thus has something to say. Snyder has nothing to say about rape, using it first as a “call to action” in defence of innocence for a previously jaded protagonist (an idea borrowed from countless Westerns), and then in an unfortunate callback to the homophobia of David Lynch’s Dune (1984). Scene-wise, in a riff on the Mos Eisley Cantina from Star Wars, we see a grotesque and rotund alien man try to purchase one of the human heroes as a gay-sex slave. This is all needless. Star Wars evoked the seediness of Mos Eisley without resorting to tasteless allusions to gang rape, trafficking, and so on. Lines like “turn a farm girl into a whore” belong in films with actual opinions about the attitudes that drive such horrors.

This and much of Rebel Moon represent a teenage boy’s idea of grown-up fiction, a mashup of heroic fantasy tropes and callow miserabilism. What Snyder and his team (including co-screenwriters Kurt Johnstad and Shay Hatten) fail to grasp about their source material is that science fantasy stories like Star Wars succeeded thanks to their likeable characters. Luke Skywalker was a vulnerable, hopeful protagonist; Darth Vader an exciting and mysterious villain; Princess Leia a spunky heroine; Han Solo a charming rake, etc. Star Wars had humour, joy, and suspense. Where is any joy in Rebel Moon? The mystery, the charm, the sense that this is a galaxy where something wondrous and unexpected unfolds?

While heroic fantasy might provide fertile ground for epic narratives, I argue that science fantasy simply can’t sustain the suffocating nihilism that Zack Snyder embraces unless the author possesses exceptional character development or other redeeming elements. Heroic fantasy thrives on the very existence of heroes. Yet Rebel Moon’s tagline plastered on the poster proudly declares, “There are no heroes. Only rebels.” Without aiming for malice, I can’t help but see a 15-year-old raised on sci-fi, yearning to create art, taking their familiar tropes and layering them with vaguely understood adult themes like war, oppression, revolution, sexual assault, and existentialism, gleaned from snippets of overheard conversations rather than genuine comprehension. It’s important to note that Zack Snyder is, in fact, 57.

On the upside, his basic storytelling exhibits a touch more elegance and visionary flair (of a grand vision, no less) than his detractors acknowledge. While watching Part One: A Child of Fire, I repeatedly felt that I might have enjoyed it more, or at least admired it more deeply, as a graphic novel. Many shots looked primed for vibrant comic book panels or dramatic splash pages. The slow-motion fight scenes and kills, with their exaggerated movements, even evoke those “live-action” comics where panels offer a hint of animation (think wind billowing the hero’s cape, for example).

Zack Snyder’s films often remind me of the bombastic, hyper-stylized comics that flooded the shelves in the 1990s. Sure, these weren’t the works of legendary storytellers like Alan Moore or Frank Miller at his peak, but they overflowed with outlandish “extreme” concepts. Watching a Snyder film feels akin to flipping through a Rob Liefeld or Todd McFarlane graphic novel—names that still spark groans from seasoned comic fans. It’s big and flashy and crammed with grim-dark violence, moody speeches, and nihilism… but it signifies little except, maybe, itself.

USA • HUNGARY • SWEDEN • DENMARK • UK | 2023 | 134 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Zack Snyder.

writers: Zack Snyder, Kurt Johnstad & Shay Hatten (story by Zack Snyder).

starring: Sofia Boutella, Djimon Hounsou, Ed Skrein, Michiel Huisman, Doona Bae, Ray Fisher, Charlie Hunnam & Anthony Hopkins (voice).