THE HIDDEN FORTRESS (1958)

Lured by gold, two greedy peasants unknowingly escort a princess and her general across enemy lines.

Lured by gold, two greedy peasants unknowingly escort a princess and her general across enemy lines.

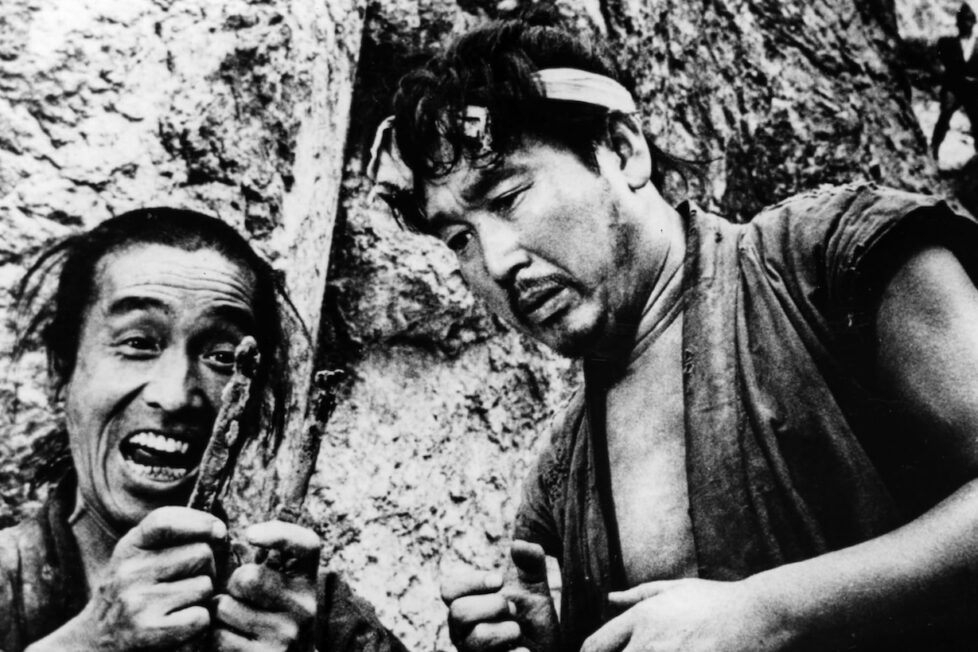

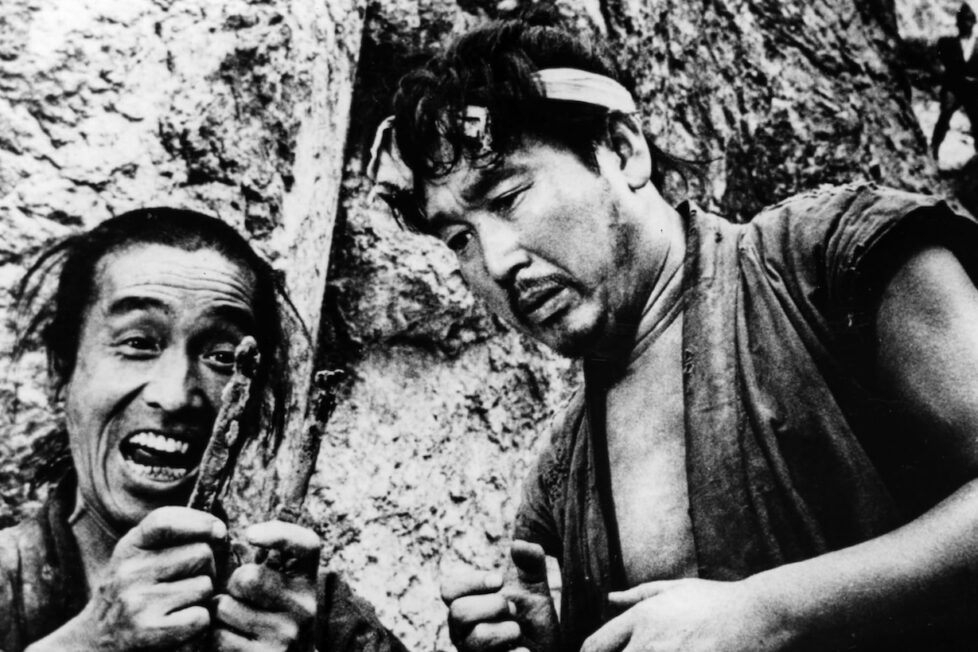

A vast, desolate wasteland unfolds before our eyes. Distant, towering mountains rise above a barren, scorched landscape. Two lowly peasants, dirty and bedraggled, begin to criticise the other: both reeking of death. Despite their attempts to participate in a conflict between two rival factions, the Akizuki and Yamana clans, they were mistaken for being members of the losing side. As a consequence, they were forced to bury the corpses of the Akizuki, while the Yamana watched. “You stink of dead bodies!” Tahei (Minoru Chiaki) exclaims with disdain. His friend, Matakishi (Kamatari Fujiwara), retorts, “We both stink of dead bodies! And it’s all your fault!”

This prologue of The Hidden Fortress / 隠し砦の三悪人 is reminiscent of a Shakespearean opening. Through skilful exposition, we are introduced into a world with pre-existing conflict like that of Hamlet. Additionally, morbid themes are loudly announced through the two peasants’ macabre preoccupation with death, which is redolent of the opening in Macbeth; Kurosawa actually adapted the Scottish play the year prior, with Throne of Blood (1957). However, though the narrative roots of Akira Kurosawa’s jidaigeki epic have a clear connection to theatre, the Japanese auteur never misses an opportunity to maximise the potential film has to offer. Our duologue is interrupted as a crazed, frenzied samurai enters the scene, and is then chased and speared down by soldiers on horseback.

Such is the scope of Kurosawa’s classic, which, much like the rest of his oeuvre has proven to be, was highly influential on Western cinema, most famously inspiring the likes of George Lucas’ Star Wars (1977). The story follows those two peasants after they’re enlisted by General Rokurota Makabe (Toshiro Mifune) to help him and Princess Yuki (Misa Uehara) cross into the safe region of Hayakawa. He promises them a fortune in gold if they succeed, but their journey will demand every ounce of Makabe’s cunning.

Although The Hidden Fortress may not possess the emotional depth that characterised some of Kurosawa’s previous films, there’s still much to treasure in this story. It’s been hailed as a flawless adventure film—a fitting description, given it’s packed with exhilarating chases, mischievous ploys, daring escapes, and pulse-pounding fights. The story is further aided by entertaining characters who, despite often resembling caricatures, serve to create great conflict in every scene. Perhaps most importantly, The Hidden Fortress remains captivating even after 65 years due to its exquisite cinematography—each scene resembling a painting come to life.

When General Rokurota Makabe makes his entrance into the plot, he has ‘hero’ written all over him. While we may have spent the first few scenes with the two destitute peasants, it becomes clear they were merely a placeholder, paving the way for the arrival of the true star of the show. This is where we can observe where Lucas found inspiration: he openly acknowledged that the trope of narrating a tale through the eyes of the two lowest-ranking characters inspired Star Wars. R2-D2 and C-3PO, the iconic droids, are direct homages to Hidden Fortress’s two thieves. Additionally, Princess Leia is based on Princess Yuki, Darth Vader on General Hyoe Tadokoro, and the characters even use some kind of primitive, steel lightsabre.

Toshiro Mifune, who had collaborated with Akira Kurosawa on 16 feature films, delivers a groundbreaking performance as the crafty, wise samurai. Before this role, Mifune had played a samurai on several occasions. He first starred in Kazuo Mori’s Vendetta for a Samurai (1952), then took on a supporting role in Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai (1954), portraying the chaotic, destructive character Kikichiyo. In that same year, he appeared in Hiroshi Inagaki’s Samurai trilogy (1954-56).

While Mifune’s previous roles were often characterised by either refined manners or unruly behaviour, his performance in The Hidden Fortress marked a departure from these archetypes. Instead, his character is neither polite nor chaotic but falls somewhere in the middle to create a personality defined by churlish nobility. Both wily and cunning, he utilises his sharp intellect and vast experience to outwit a multitude of foes. His proficiency with a katana is undeniable, but he resorts to its use only when practical options fail to present themselves. This trope of the sage, gruff hero resurfaced in Mifune’s subsequent performances in Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962).

Mifune’s monosyllabic performance exemplifies an anachronistic masculine ideal. He never reveals any weakness, is taciturn, and occasionally even exhibits cruelty. He uses his intelligence to manipulate those around him, but this is never framed as being duplicitous; as his goal is just, so are his methods. Furthermore, he’s only manipulating the base and ignoble peasants, who are slaves to their fears and impulses. Since they’re unable to govern themselves, the superior Makabe must. This archetype has much in common with the terse John Wayne, while it can also be seen to have directly inspired Sylvester Stallone’s John Rambo and Clint Eastwood’s laconic character in The Man with No Name trilogy. Indeed, the plot elements and main character of the latter were so similar to Kurosawa’s Yojimbo that a lawsuit was filed against Sergio Leone!

The stoic demeanour of General Rokurota Makabe is symptomatic of a problem in The Hidden Fortress: there is no emotional resonance. The film’s narrative places an emphasis on intelligence and fortitude triumphing over fickle desires, effectively suppressing any expression of genuine human feeling. This lack of emotional catharsis, while not entirely detrimental to the film’s entertainment value, prevents it from penetrating deeper emotional levels. Despite its superb plot, the film’s clinical approach to storytelling inadvertently downplays the gravity of suffering and existential turmoil, presenting them as mere transient challenges to be faced with a detached, phlegmatic disposition. Even amid their demise, Princess Yuki sings a ballad with unwavering poise, while Makabe listens in stolid respect. We are not moved because neither are the characters.

Owing to this, the film occasionally gives the impression of being merely a plot; comparatively, there’s rather little story. There is no backstory provided for the two peasants, nor a ghost haunting Makabe, nor any dramatic character growth for Princess Yuki. One of the chief antagonists experiences a moment of redemption, but beyond this, the characters remain mere archetypes and little more. They may be convincingly performed, but their portrayals are destined to be superficial as there’s no material for deeper insights into their characters. The narrative then becomes a basic parable, albeit one that’s wholly entertaining. It conveys the importance of nobility and stoicism while condemning sinful desires such as lust and greed. While various aspects of the plot feel as though they only take place on the surface level, there’s enough thematic didacticism to provide substance, even if the characters do not.

If a film is to take place primarily on a surface level, it would behove it to have an appealing and visually striking surface like that of The Hidden Fortress. The cinematography is simply stunning. Kurosawa’s background as a painter shines through. Shot in Tohoscope, the Japanese equivalent of the US anamorphic widescreen format, the film boasts an expansive aspect ratio of 2.35:1. This results in a cinematic experience that feels more like viewing a tapestry than watching a movie. Sweeping landscape shots are mesmerising, almost overwhelming in their grandeur. The scene depicting the prisoners’ uprising is jaw-dropping in its epic scope. As the slaves storm the castle steps, the legions of extras contribute to a monumentality reminiscent of Metropolis (1927). One can only imagine the experience of witnessing this scene unfold on the big screen.

Beyond its narrative brilliance, The Hidden Fortress showcases truly remarkable action sequences. Despite being over six decades old, its battle scenes retain an exhilarating intensity that rivals modern action films. In the opening scene, a team of samurai on horseback relentlessly pursue and slay a runaway soldier, providing a thrilling prelude to the film’s epic horse chase that would put any sequence in the Fast & Furious franchise to shame.

As Makabe realises their position is about to be exposed, he mounts a horse and gallops after his enemies, sword raised high. This daring stunt is filmed from a distance, emphasizing the rawness and immediacy of the action. While strategic editing adds to the chase’s intensity, the majority of the sequence is captured from afar, allowing us to marvel at the authenticity of the stunt. The Hidden Fortress’s action scenes stand as a testament to the enduring power of cinematic storytelling, proving that age is no barrier to producing thrilling and impactful visual sequences.

The film may not be particularly poignant, but it doesn’t have to be. It’s a simply excellent adventure movie. With a compelling plot and a few superlative action sequences, the movie is further elevated by breathtaking cinematography. When combined with its significant influence, the film’s quality becomes even more apparent. The film simultaneously serves as a master class in composition, plot structure, and direction. While it may not be Kurosawa’s finest work, that’s by no means a criticism; the Japanese auteur contributed so many diamonds to cinema that a few are bound to shine less brightly than others. The Hidden Fortress may not sparkle as brightly as Seven Samurai or Ran (1985), but it remains a jewel nonetheless.

JAPAN | 1958 | 141 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

director: Akira Kurosawa.

writers: Ryūzō Kikushima, Hideo Oguni, Shinobu Hashimoto & Akira Kurosawa.

starring: Toshiro Mifune, Misa Uehara, Minoru Chiaki & Kamatari Fujiwara.