POLTERGEIST (1982)

A family's home is haunted by a host of demonic ghosts.

A family's home is haunted by a host of demonic ghosts.

They’re still here! 40 years on, and murmurings continue about remaking the 1980s classic Poltergeist. Even after the lukewarm reception the 2015 Sam Raimi-produced rehash received, the Russo brothers (Avengers: Endgame) have been talking about their love for the movie and teasing a possible reboot. Poltergeist is one of those films that, if seen at the right age, embeds itself into the psyche and gets mixed up with one’s own half-remembered childhood dreams and nightmares. It’s like a revenant that won’t stay buried.

Poltergeist managed to see off stiff competition to become the most successful horror movie of 1982, and one of three genre films to make the box office top 10 that year—the others being Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and E.T. the Extra-terrestrial, which outperformed everything else to take well-over twice as much as its closest rival, Tootsie. Poltergeist is very much a product of the ’80s, often recalled with so much associated nostalgia it’s difficult to understand how refreshing it was at the time. After a decade of increasingly extreme horror movies, it reclaimed the genre for the mainstream, demonstrating to distributors that it could still be lucrative.

Steven Spielberg was already being called Hollywood’s new wunderkind after he’d smashed box office records with a string of hits including Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) which had been written and co-produced by fellow golden boy George Lucas. Between them, they ushered in the age of the mega-blockbuster and pretty much saved cinema. Raiders of the Lost Ark was the most successful film of 1981 and producer Frank Marshall was eager to strike while the iron was hot. So, although Spielberg was already underway on a follow-up to Close Encounters, they also began parallel development for the Spielberg-scripted story that became Poltergeist. Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre) was hired as director while Spielberg got busy developing and directing E.T.

Once again, we’re in the company of ‘the Spielbergian family’. The Freeling’s dynamic is almost the same as those we see in Close Encounters, until Roy Neary becomes obsessed with UFOs, and very much like the Taylor’s before Elliott finds a little alien in the shed. The Poltergeist family even have what could be the same golden retriever! A Spielbergian family is painted with attention to domestic detail: it satirises middle-class, aspirational America, but its also laced with sentiment as they face adversity to come through it together with their familial bonds tested and reaffirmed.

The Freelings are unremarkable—wholesome in the way they care about each other and want the best for each other and will stand together in a crisis, yet not so stereotypical that they don’t enjoy a beer or relax with the occasional joint after the kids are tucked-up for the night. But they’re as far removed from the dysfunctional Gothic family as their home is from the crumbling castles and debauched aristocrats found in the tales of Edgar Allan Poe and the films of Roger Corman. They could just as easily be your neighbours.

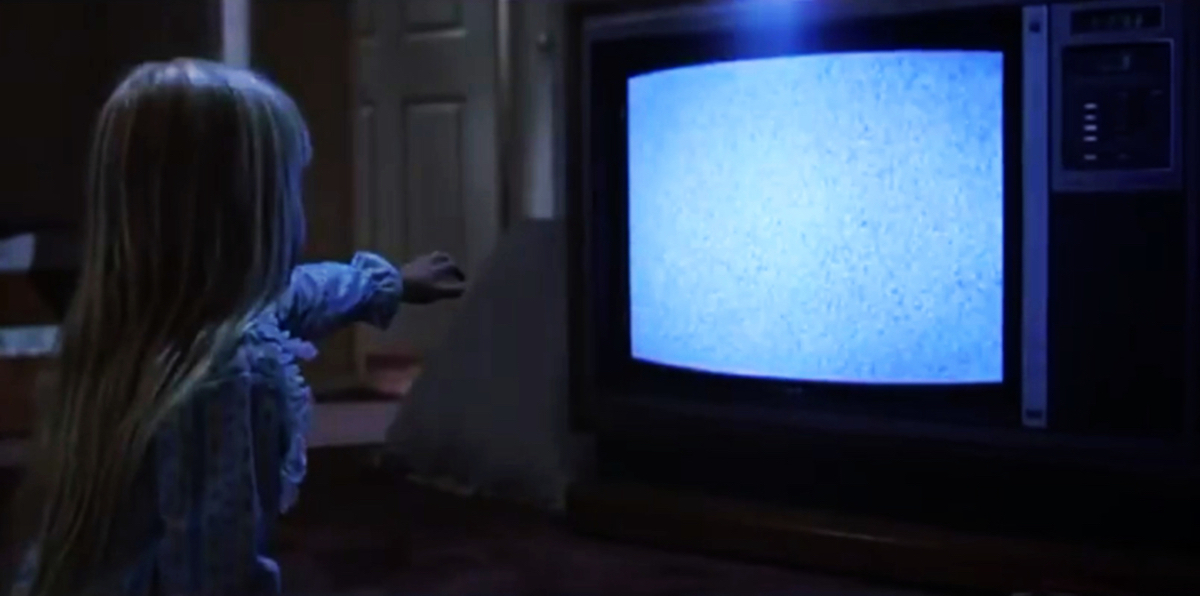

The opening of Poltergeist is still so evocative of a bygone age as the television closes down and bathes the room with strobing static. Do any TV channels still play their dreary anthems at close-down? Do they even ‘close-down’ in the digital age? Whole generations have missed out on that experience now. I mourn the days of the dead channel when our cathode ray tubes tuned into the cosmic background radiation, beaming the aftershock of the Big Bang right into our living rooms, playing back the birth of the universe. It was a wonderous glimpse of the mysterious beyond, which is, sort of, what it represents in Poltergeist.

The sudden burst of white noise rouses E.Buzz, the dog, who then introduces us to the family in a cleverly planned sequence as he goes room to room clearing up the unfinished snacks. The father, Steve (Craig T. Nelson), has dozed off in his favourite armchair with the remains of a sneaky supper at his side. The mother, Diane (JoBeth Williams), is slim and ‘sensible’, so her bedside table disappoints, but E.Buzz hits the jackpot with teenage daughter Dana (Dominique Dunne), who fell asleep with a nearly full bag of Lay’s Chips under her pillow. In the children’s room he finds some morsel next to Robbie (Oliver Robins) and his searching snout awakens the youngest daughter, Carol Anne (Heather O’Rourke), who’s drawn downstairs by voices only she can hear. She stands enthralled by the hissing screen where her entreaties for whoever to “talk louder” breaks the peace of the house and causes concern for her parents. No, she doesn’t say that line yet…

The next day, all seems back to normal, and we see that the family home is just one of many in a new housing development sprawling across an idyllic vale. The compartmentalised lives of average Americans seem scarily bland and boring in their capitalist complacency. No wonder the Freelings will, at first, welcome the strange phenomena that start to unfold in their household.

On one level, the film can be read as a veiled critique of how the modern U.S is built upon a murky past, steeped in death, the corporate corruption behind the American Dream and the quick-buck business mentality of Reaganomics. Steven is seen reading the 1980 biography Reagan, the Man, the President, and the creepy clown doll wears the stars and stripes as a sort of evil parody of ‘Uncle Sam’… and of course, the first thing we hear is the tune to Home of the Brave as the TV channel concludes for the night.

The first, understated, sinister inkling that a something is amiss comes when the pet canary is found dead in its cage. Miners used to carry caged birds down the shafts as indicators of noxious gas. If the bird became distressed, or died, the miners would raise the alarm and evacuate the pit. So, this subtly suggests that there could be some sort of hallucinogenic toxin seeping up from whatever lies beneath the house. A notion supported by the proliferation of dead trees that dot the estate. Perhaps it’s an illegal landfill or, just maybe, an old, abandoned cemetery.

Then, young Robbie starts to get freaked out by the old and clearly sculpted tree outside the bedroom window—especially once a fierce electrical storm rolls across the valley in the night. He’s not too keen on the big grinning clown doll that sits at the foot of his bed, either! But we’re more than half-hour in before the TV calls to Carol Anne again and she delivers that ominous line with innocent glee.

That’s the signal for things start to get proper weird. Little things like inexplicably bent cutlery for starters, but pretty soon furniture is moving around of its own volition and Diane and Carol Anne spend some quality mother-daughter time being pulled across the kitchen floor by an invisible force that tickles their tummies. But it rapidly becomes clear that this isn’t a mischievous spirit but a malevolent force coming to get them.

The first big break in their reality occurs when that terrifying tree bursts through the window into the children’s bedroom and snatches Robbie from his bed before trying to devour him. This signals the change from fun Fortean phenomena to decidedly demonic, life-threatening evil and is an abrupt gear shift to take us into the second act.

The whole sequence was achieved with a full-scale mechanical puppet tree, its limbs and twiggy fingers pneumatically animated in real time. Suddenly all subtlety goes, quite literally, out through the window as Steve fights for his son’s life, wrestling Robbie free from writhing roots as the supernatural storm rips the tree from the ground and carries it off in a tornado of darkness. But even that was just a distraction to get the rest of the family out of the house so the evil presence could abduct little Carol Anne, the object of its infernal affection.

Spielberg looked to a couple of classics for inspiration. The influence of Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon (1957), and Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963) are palpable and, here, he throws in a healthy portion of The Wizard of Oz (1939)—the twister ripping up the tree marks the transition into a removed reality in much the same way as Dorothy’s house spinning away into the air just after she’s knocked unconscious by tree branches reaching in through a shattered window.

The whole core premise seems to stem from “Little Girl Lost”, a classic 1962 episode of The Twilight Zone, written by Richard Matheson, in which a young girl goes missing from her family home. Her parents can hear her but can’t locate her whereabouts and find a portal to a parallel dimension through which she can be rescued and pulled back into our world. Sound familiar? Poltergeist comes across as a loose remake, though Spielberg neglected to acknowledge this source material at the time. It’s rumoured that Matheson was later appeased by Spielberg shrewdly hiring him to write the screenplay for Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983). It’s not unusual for Hollywood blockbusters to attract plagiarism suits and Spielberg soon got used to fending off some very convincing claims for both E.T. and Poltergeist.

Poltergeist also channels The Shining (1980), which was the last haunted house movie hit at the time, but the setting isn’t a vast and isolated hotel with a chequered past that already looks haunted. The events of Poltergeist unfold in a new-build suburban home. Steve, whose job is selling real estate, even makes the point that all the houses on the sprawling development are near identical. There really isn’t anything obvious that sets any of them apart. The influence of Stephen King can be sensed throughout and like many of his novels, we are eased-in to a familiar, real-world setting before anything fantastical occurs, which it then takes further than King ever has. Some would say too far!

After solo-writing the first draft, Spielberg then collaborated with, Michael Grais and Mark Victor, a TV writing duo who’d contributed to the likes of Kojak (1973-78) and Starsky and Hutch (1975-79). He then finalised the screenplay himself into the rather slight story we end up with. Although the narrative is simple, it’s fragmented—disjointed even—to keep things interesting.

Spielberg didn’t so much write Poltergeist as design it as one might a theme park ride. The overall result isn’t unlike a fairground haunted house or ghost train, but a particularly spectacular one realised with no expense spared. One gets the feeling that there was much more story jettisoned to get it out of the way of what is one big excuse for a SFX circus crammed with never-before-seen or heard thrills.

Feeling unable to involve the police, the Freelings turn to a paranormal research team led by Dr Lesh (Beatrice Straight) who arrives with her two assistants, Ryan (Richard Lawson) and Marty (Martin Cassella), who set up their monitoring equipment in the house, recalling a similar team in The Haunting and John Hough’s Legend of Hell House (1973)—another one scripted by Richard Matheson!

The second act closes with the infamous scene where Marty, after being sickened by watching a steak crawl along the kitchen counter, and then discovering he’d been munching on a maggoty chicken limb, runs to the bathroom and tears his own face off. Although it’s framed as an hallucination and clearly happening to an animatronic head with motorised eyeballs, it’s still pretty strong stuff that doesn’t fit the overall tone or belong in a PG-rated movie.

The script had simply called for a brief glimpse of himself in the mirror as a corpse. Which makes more sense, following on from the animated meat and decaying flesh of the previous scene, all highlighting the underlying theme of existential angst—the realisation that we’re prisoners of our own flesh which will, one day, exceed its ‘best before’ date. Apparently, the gorier version—which is intended to unsettle the audience—was down to the enthusiasm of special make-up supervisor Craig Reardon who was responsible for most of the ambitious prosthetic effects, whilst simultaneously working on the body of the E.T puppet.

The earlier Wizard of Oz reference sets us up to think that perhaps ‘the beast’ is pretending to be something it’s not, especially when diminutive medium Tangina (Zelda Rubinstein) is called in and tells us that it lies to Carol Anne. But what is it really? A minor demon? A vengeful revenant?

Hey, it’s supernatural, so doesn’t need to be fully rationalised. Sometimes, that helps conjure the atmosphere of mystery. Other times it just seems like lazy writing. We don’t get a fully formed exploration of the motivations involved. It’s just angry spirits and that supposed to be enough. We’re not told why it focusses on the Freeling family. We are thrown a few clues, for instance it seems that Carol Anne is the first child to have been born on the housing development, but beyond that, we’re left guessing. This isn’t a problem when immersed in the action and clearly didn’t bother its ’80s audience one bit.

“They’re hee… ere” is now familiar to those who have never seen the movie, and Tangina proclaiming “this house is clean” was even paraphrased by Jim Carey as Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (1994). These two oft-quoted phrases are up there with others of Spielbergian origin, “you’re gonna need a bigger boat,” and, “E.T phone home.”

Poltergeist stands the test of time as a thrill ride delivered with great gusto by all involved. Some of its VFX, state of the art work from Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) at the time, may now seem rather quaint. Others are still fine works of movie magic. The second manifestation of ‘the beast’ as a pale, attenuated, skeletal figure writhed in wispy hair and ethereal light is one of my all-time favourite animatronic monsters.

The entire production now seems like a nostalgic ‘swansong’ to old-school practical effects that were soon to be overtaken by the CGI revolution. Poltergeist is nothing if not a spectacular SFX showcase—an impressive mix of miniature shots, life-size mechanical effects, prosthetics, puppetry, and matte paintings alongside what was then cutting-edge wizardry. Much remains mind-boggling. All the more so because we can sense its physicality. On some level, we know most of what we see was happening for real, right in front of the lens. Thus any sense of unreality, instead of being unconvincing, only adds to the uncanny.

The special effects list started on the second page of the script and nearly every scene had both mechanical and optical effects involved, whether that be a matte painting to extend the housing development, or a giant skull wreathed in smoke crashing out from a blazingly bright closet…

The memorable sequence when Diane is molested by the malevolent presence and dragged across the ceiling of her bedroom was created by using a full-size duplicate set with everything stiffened and bolted down so when the entire room was rotated, Diane appears to defy gravity. This was a scaled-up version of an effect devised by Mario Bava for his haunted house movie Shock (1977), which shares more than a few similarities, though its tone was far more subdued and sombre.

The room with the levitating toys whirling about, a Harryhausen style centaur galloping through the air, a red vinyl record being played with a compass point, was constructed by Rick Fickler at ILM and each item was animated separately as a travelling matte and then composited with chromakey. For the time, amazing, though it now looks very 1980s and endearingly clunky.

Many of the breathtaking effects are enhanced by some truly inventive and intricate sound design supervised by Steven Flick, who’d just worked with Spielberg on Raiders of the Lost Ark. The sound of Poltergeist is essential in conjuring the atmosphere of unease and incremental evil. There are an estimated 120 tracks per reel, including special sounds created by Mark Mangini and Alan Howarth. For the most part, they sourced real world sounds so that there was always a sense of realism. The deep guttural roars of the beast, for example, were a mix of elephant trumpeting, horses, lions, and tiger growls all overlaid, slowed down, fed through effects ‘pedals’, and some reversed. It all works beautifully when combined with the score by Jerry Goldsmith, his first for Spielberg.

It’s generally remembered as a Spielberg movie—mainly because it was—but Tobe Hooper is credited as director. He’d had attracted Spielberg’s attention with his notorious sophomore feature The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. There have since been many varied and contradictory stories about just how the creative dynamic worked on set and many are of the opinion that Hooper was just Spielberg’s ‘yes’ man, a director in name only.

It seems that Spielberg acted like an old-time producer and was on set to oversee the disparate elements involved, and to contribute his ideas. Hooper is said to have ‘deferred to the writer’ when more than one viable option for a shot presented, in other words, he wisely let Spielberg guide him. However, Hooper was doing the job that a director is there to do, which is direct the actors. Though I’m sure Spielberg also had some input with that!

Hooper certainly wasn’t taking the helm as an auteur, which isn’t surprising given the nature of the production. It had to be a collaborative effort with the logistics of shooting on several different sets, and on location, managed by the construction and production departments. The SFX teams had already designed more than 100 practical effects sequences and certain shots had to be filmed in a very prescribed ways for the ILM team of 50 technicians, led by Richard Edlund, to produce and composite later.

So, there’s no denying Spielberg had a big hand in the direction, but while he was away in Hawaii with George Lucas to promote Raiders of the Lost Ark there, Hooper was on the ground every day. Which is partly why Hooper received compensation when Spielberg’s name was more prominent in the credits and marketing. Spielberg was also prompted to clarify how their collaboration had worked acknowledging Hooper’s essential directorial role.

Whilst the entire production is an admirable achievement, it’s the archetypal motifs of Poltergeist that ensure its lasting appeal. It effectively conveys a supernatural world that should run parallel but overlays ours so closely that they sometimes overlap. This is an age-old view of the ‘otherworld’, tapping into the same subconscious realm that conjured, fairies, ghosts, angels and demons for our ancestors. It’s latching onto a deep human need to believe in something more than just this physical world we share, some great beyond, an afterlife. In this respect, Poltergeist is more of a classic portal fantasy than a horror.

This was all deliberate, the main drive behind Spielberg’s first draft and it paid-off. It is a scary movie. Over the decades, I’ve seen it top more than one list of ‘Scariest Films Ever.’ But it’s a sort of safe kind of scary; not too edgy and although psychologically disturbing in parts, often diffused with humour. It exploits common childhood fears that ring true but are things teenagers have already come to terms with. Which is why the age of the youngest children are 5 and 10 with the older, teenage sister feeling like a spare part in the story—she isn’t called upon to do much except get a bit hysterical and add to the noise.

The portal to other realms is a trope that has captured human imagination as far back as the first stories ever told. A mainstay of fairy tales, many that feature a little girl being lost in another world—Little Red Riding Hood is an obvious example that also features a child being deceived by a ‘beast’. In days of yore, it was the deep dark woods that would’ve been a familiar and daunting reality to many children. Here, that familiar fear is evoked by those things that daunted many of us in our modern world: the monster in the closet, something that lurks under the bed, the freaky doll that moves when you look away, a tree with gnarly branches that look like crooked fingers tapping against bedroom windows on stormy nights…

USA | 1982 | 114 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Tobe Hooper.

writers: Steven Spielberg, Michael Grais & Mark Victor (story by Steven Spielberg).

starring: JoBeth Williams, Craig T. Nelson, Beatrice Straight, Dominique Dunne, Oliver Robins, Heather O’Rourke & Michael McManus.

1 Comments

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

This seems to work off a quick – if nicely thorough (it’s true the film was inspired through a number of “Wizard of Oz” allusions) – skim of information that isn’t entirely accurate at all points. For instance, Spielberg never wrote an initial first draft. He wrote a treatment, in collaboration with Hooper. Hooper was the one doing full pre-production, so when you say this was never an “auteurist” film for Hooper, it in fact was, from the writing to and throughout the production. Very few people can say with any detail or authority how Spielberg “essentially” directed the film, although there are a number of anomalies in the production that point to a director who didn’t want just to make the Spielberg “designs” before him. It’s true Spielberg added all the monsters and roller coaster aspects with Grais and Victor, but Hooper’s story sense and surreal intensity come through in its commentary on death and modernity. You mention “Curse of the Demon” and “The Haunting” – two films Hooper has repeatedly mentioned as being at the top of his favorite horror movie lists. In other words, there is just as much reason to believe this is an auteurist work of Hooper’s as much as it is Spielberg’s.