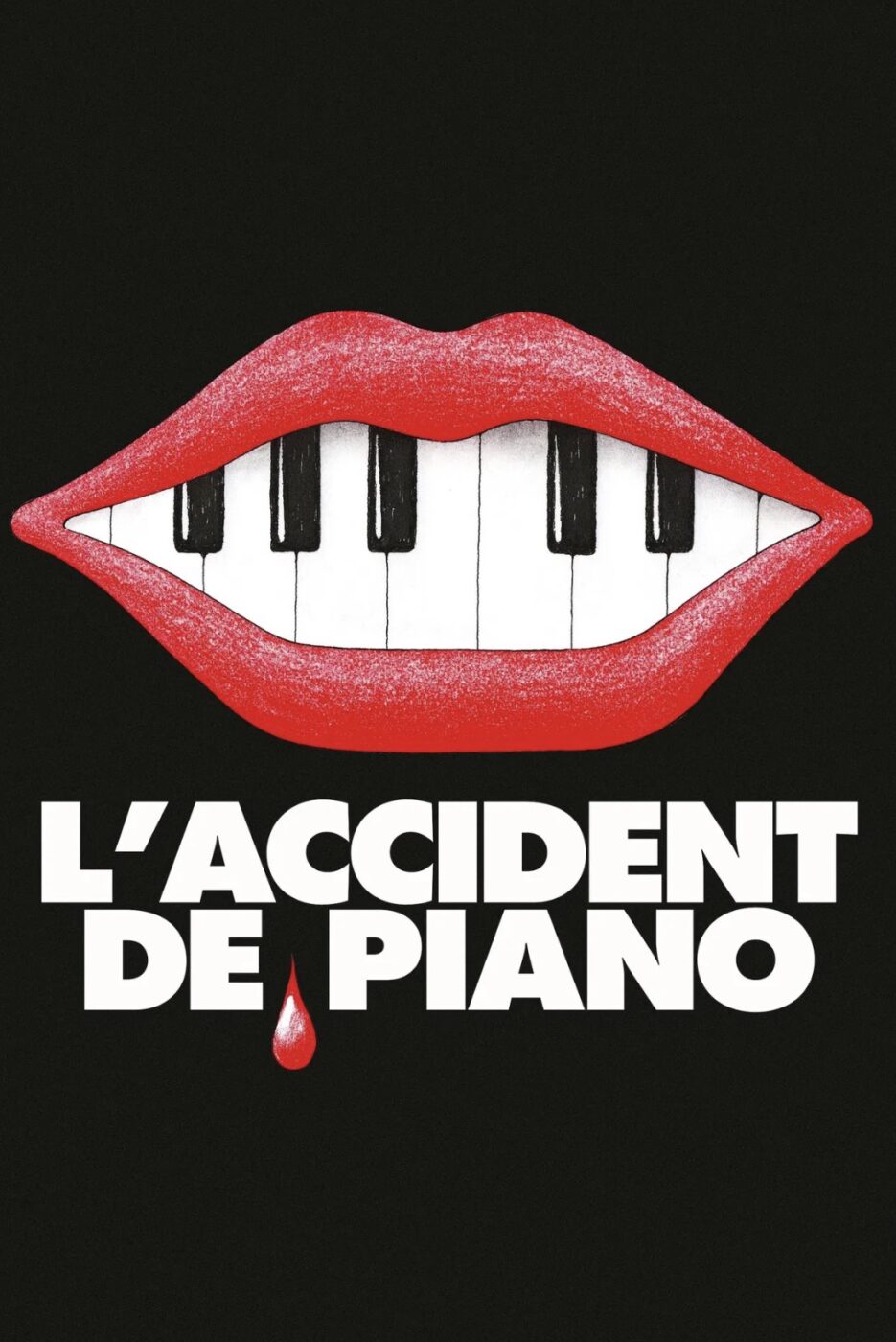

THE PIANO ACCIDENT (2025)

A social media star famous for posting shocking content takes a break after a mysterious incident, only to be blackmailed by a journalist...

A social media star famous for posting shocking content takes a break after a mysterious incident, only to be blackmailed by a journalist...

Quentin Dupieux’s recent filmography is emblematic of everything that is right and wrong with improv, ranging from fascinating twists to aimless meandering and childishly constructed scenes. It takes a naïve, fantastical dreamer to conceive of his premises, all of which peter out to some degree as they wind down to their denouement. At his best, you’ll only realise the disaffected way you view his films in retrospect: Yannick (2023), which follows a dissatisfied theatre-goer who takes a production’s audience and performers hostage, fits this bill. It’s excellent, until it isn’t. The fun must end, and the social experiment inevitably grows taxing. This is a recurring pattern in many of Dupieux’s films.

Other improv experiments have proved less successful, though usually no less daring. The Second Act (2024) was a constant “yes, and” exercise in nonstop metafiction, where layers of dramatic content are peeled back to reveal the underlying truth. The result was a slow-burn film that somehow felt dizzying, thanks to four spectacular lead performers who constantly reinvent themselves in real-time. As they shift their personalities to conform to different versions of reality, and as the audience realises they’ve seen yet another layer of metafiction, it isn’t always easy to keep up.

But all this wandering—both figurative and literal, including a “walk-and-talk” scene so long it’s been proclaimed the longest tracking shot in cinema history—gives way to emptiness once you finally peel back the layers. That hollow shell could never be as interesting as the tireless search for it. You’re left feeling empty, either through disaffection or mild annoyance.

In these moments, it’s as if Dupieux is peering over your shoulder, grinning widely, encouraging you to laugh raucously at how half-heartedly he explores social issues, or the way he hardly seems to care about these characters at all (despite going to great lengths to bring them to the silver screen). But what do these experiments amount to? Are they worth a damn if you feel nothing by the end, as the air of improvisation wears thin?

Similar questions are asked of Magalie Moreau (Adèle Exarchopoulos), the protagonist of the French director’s latest film, The Piano Accident / L’Accident de piano. As a social media star who found fame in the early days of online content creation through self-mutilation, she’s a tough nut to crack. Years after her first video, Magalie is detestable, spitting out words like venom and contorting her face into an expression of distaste every few seconds—the same expression she once made when she experienced pain.

There’s seemingly no catharsis or purpose to her suffering. Just pain, again and again. She can conceal it well, or perhaps she doesn’t feel it at all anymore. Nowadays, she doesn’t offer so much as a grimace during her daring stunts, making it impossible to connect with her emotionally. Her rise during the early days of content creation, before platforms were so saturated, has provided her with more money than she can use. She takes no pleasure in fans, fame, or fortune. So why continue to put herself through misery?

It’s a question journalist Simone Herzog (Sandrine Kiberlain) is eager to answer. Blackmailing Magalie after discovering the truth behind an accident that left the megastar with numerous injuries, Simone—like the protagonist—isn’t actually interested in money. In fact, she’s something of a contradiction. Simone claims her career doubts are assuaged by the need to pay for her upkeep and that of her ailing mother. If that were the case, why wouldn’t she demand an absurd amount of money from Magalie? Her brother did exactly that, having had the bad sense to gossip about the incident to his journalist sister after being paid off.

Despite how much Magalie, ever the unwilling interviewee, would prefer it, Simone isn’t the primary subject of interest here. Unfortunately for the journalist, she has an arduous road ahead. Magalie is an enigma who refuses to justify the rationale behind her life’s work—probably because no such rationale exists.

There have been numerous cases of people torturing themselves on-camera for entertainment. Notably, a Frenchman named Raphaël Graven, known online as Jean Pormanove, died on a livestream in his sleep just a few months ago. He was part of a streaming group whose members regularly subjected him to abuse for the enjoyment of viewers. He was one of the most popular creators on the platform Kick. If you want to depress yourself further, you can read the harrowing details regarding the end of his life and the abuse he endured.

While Graven’s death is a tragedy, it’s by no means unheard of online. Magalie’s self-mutilation is “light work” compared to some of the depravities that have lingered, unchecked, for months on the world’s biggest livestreaming platforms. In Dupieux’s native country, there has naturally been more recent awareness of this issue, while other creators have gone to great lengths to expose abhorrent abusers.

The Piano Accident, like Magalie herself, is totally averse to offering a path towards understanding or sympathy. Exarchopoulos’ unnerving mannerisms and pointedly unattractive appearance—a sharp contrast to her natural looks—operate as both a self-conscious performance for Magalie and an instinctive display of her authentic self.

Where does the performance end and the person begin? What motivates someone to harm themselves? Why is anyone interested in this content? The Piano Accident doesn’t ask these questions, let alone answer them. Simone puts forth a few theories that hint at these avenues, but Dupieux is just as uninterested as Magalie in uncovering answers. This protagonist’s overworked handler, Patrick Balandras (Jérôme Commandeur), is similarly uncaring.

This is a film centred on timely discussions with no curiosity whatsoever about what makes them timely or worthy of debate. Each scene is protracted, hoping for sparks to fly between Exarchopoulos’ viscerally disgusting depiction of Magalie and the more “normal” characters. While this unglamorous lead role is intriguing, it never presents anything amusing or clever, let alone substantive.

The Piano Accident is a half-hearted shrug in the direction of the abusers, victims, and self-mutilators caught in the terrifying vortex of “audience capture”—the concept of being compelled to deliver exactly what a pre-existing fanbase expects. But perhaps even that is too definitive a statement for such a proudly meandering and pointless cinematic experience. The film is repugnant for the sake of being repugnant, rather than horrifying the viewer in aid of emotional discovery or philosophical open-endedness. Nothing is scrutinised, everything is bizarre, and every iota of the running time only serves the bloated ramblings of Dupieux’s ego.

That the film is never dull is to be expected from a writer-director who understands when his sequences reach their limit. It’s the bigger picture—the indulgence of passing these experiments off as feature films—that eludes him. There’s no doubting how prolific Dupieux has become, releasing two films in both 2022 and 2023, but this pace exposes how hastily many of these narratives are patched together.

FRANCE | 2025 | 88 MINUTES | 1.50:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH

writer & director: Quentin Dupieux.

starring: Adèle Exarchopoulos, Jérôme Commandeur, Sandrine Kiberlain & Karim Leklou.