ONE FROM THE HEART (1982)

A Las Vegas couple have a fight after living together for five years, so go out and celebrate the Fourth of July, each with a new partner.

A Las Vegas couple have a fight after living together for five years, so go out and celebrate the Fourth of July, each with a new partner.

When we chart the career of a major director, it can be all too easy to become fixated only on their biggest hits. The works that establish a director like Francis Ford Coppola firmly within the canon of great film directors are, undeniably, masterpieces. Not only are they themselves great films, but they have come to represent greatness—a broad, subjective concept in film discussion, occasionally unified by examples like The Godfather (1974) or Apocalypse Now (1979). A wide consensus agrees that the vague and mercurial nature of “greatness” in cinema can be found in these films. They are era-defining and epochal.

Certainly, these are rich and worthy films that deserve continued discussion. However, Francis Ford Coppola is an artist of such intrigue and complexity that by narrowly focusing on just a few of his films, we lose some of our understanding of him. Within Coppola’s filmography, there exists a sort of “shadow career,” a vast and compelling wealth of B-sides that, as a whole, forms a body of work just as compelling as his A-sides. For every Godfather, there’s a Rumble Fish (1983), and for every Apocalypse Now, there’s a One from the Heart.

The latter of these films finds new life with this stunning new 4K remaster, which also functions, according to Coppola and co., as a “reimagining” and “refinement” of the film. Six minutes of additional footage have been incorporated into what’s billed as One From the Heart: Reprise, forming what’s supposedly Coppola’s complete vision of the original film.

He’s no stranger to revisiting and retooling his earlier works. In 2019, I reviewed Apocalypse Now: The Final Cut here, while almost two decades earlier he produced a “Redux” version of the film. Similarly, 2020 saw the release of a re-edited version of The Godfather Part III (1990), titled The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone. In each case, Coppola has suggested that the reworked films are closer to his original vision—One From the Heart: Reprise follows this tradition.

There is a cynical lens through which one can view these endeavours. Is it a coincidence that The Godfather Coda and Apocalypse Now: The Final Cut both fell on milestone anniversaries of the original films? Are we being served, essentially, the same meal each time, with a minor change in toppings to persuade us to part with our money and interest? It’s quite plausible; but the motives of a business and the motives of an artist can occasionally dovetail, and it would be reductive to assume that Coppola revisits his previous works solely for a financial gain.

Many an inkwell has run dry chronicling the man’s obsessions and his quest for perfectionism, not to mention his emotional volatility. The story of Coppola throwing his Academy Awards out of his window when he was struggling to finance Apocalypse Now is now part of Hollywood legend. It’s no surprise that, decades later and with a much calmer temperament, he would find himself revisiting and correcting what he views as past mistakes.

One From the Heart: Reprise is less of a correction and more of a completion of the film that was conceived over 40 years ago; Coppola himself had called the film screened in 1982 “unfinished”.

This is Coppola re-engaging once more with perhaps his most personal film, lavishing the love upon it that it failed to receive on its original release. The director had bankrupted himself by self-financing One From the Heart, which only grossed $636K at the box office against a $26M budget. Critical reception was also decidedly mixed. Despite this, Coppola has stated that he loves the film—and with Reprise’s release, it’s easy to see why….

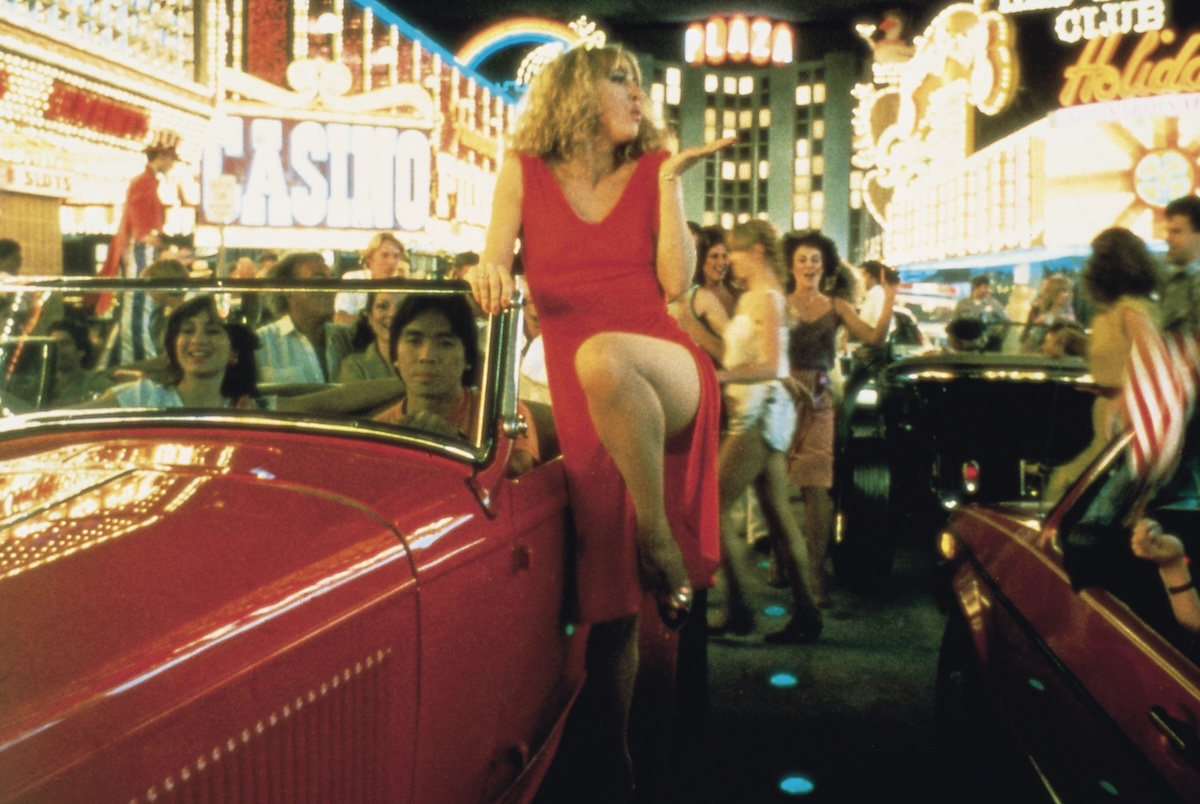

As the clouds part above the desert, and the sands blow like ancient ghosts, we’re introduced to a version of Las Vegas that is almost mythical. Matte paintings, female torsos sculpted in the sand dunes, and finally, neon signs (bearing, ingeniously, the film’s credits) all hint towards a reproduction of a forgotten empire, littered with half-buried relics.

Even before this, Coppola opens the film with the parting of blue velvet curtains, signalling that the artifice to come is entirely deliberate, that what’s depicted is an embellishment of the world we know. It’s an embrace of the inherent fakery of theatricality. And what place could be more phony than Las Vegas—a city that replicates landmarks from around the world, transforming them into oversized souvenirs, and replaces starlight with the perpetual glow of neon lights.

Las Vegas, we are told, is a place where any ordinary person can strike it lucky, and turn a small sum into a vast fortune—the American dream writ small. Coppola’s crucial decision to recreate Las Vegas entirely on the soundstages of Zoetrope Studios (co-owned by Coppola and George Lucas) suggests that beyond the razzle-dazzle, the limitations of the dream are akin to the fake city itself, hemmed in by an almost-invisible ceiling.

The jaw-dropping grandeur and detail of the sets never attempt to hide the falseness inherent in their construction—it is the work of artists who purposefully incite the audience to question: ‘How did they do that?’. The production design by long-time Coppola collaborator Dean Tavoularis is spellbinding, employing enormous casino facades, bustling streets, and desert junkyards to create a dream-world version of Vegas. It would seem like showing off, were it not so thematically relevant and downright impressive.

If the real Las Vegas is a fake city, then this is a pale imitation of an imitation—bringing to mind the sets within sets of Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York (2008). Here, all the world’s a stage, and at the centre are a warring couple.

They don’t spend their time in casinos—in fact, no casino interior is pictured in the film at all. Instead, like many others, they gamble on each other. They’ve been together for five years, having met on the Fourth of July, American Independence Day. Perhaps they see this as a good omen before taking a chance on each other; “may our relationship be filled with fireworks and celebrations, and may we never be independent again,” they seem to be saying. However, things are clearly fizzling out between them.

Hank (Frederic Forrest), a mechanic who yearns to put down roots in Vegas, even suggests to Frannie (Teri Garr) at one point that she needn’t worry about contraception—wouldn’t it be alright if they had a baby? Meanwhile, Frannie, a travel agent, meticulously curates the immaculate window displays in her workplace, advertising far-flung paradises. If only they weren’t trapped behind glass and made of cardboard.

Frannie is often seen striding around the house naked or otherwise scantily clad, as if performing for an invisible audience. Hank, by contrast, frequently wears a pair of rather unflattering Y-fronts. Frannie longs to feel beautiful and free, yearning to escape to a place that might allow her to experience this. Perhaps this explains her anniversary gift to Hank—two tickets to Bora Bora. His gift, tellingly, is the deed to the house they share. The night before their anniversary, on the eve of Independence Day, a massive fight erupts, culminating in a tentative break-up. Whether they desired it or not, their independence is granted.

It’s a simple premise, and narratively Coppola keeps things uncluttered. In doing so, he tells a story that speaks a universal language, one of longing, frustration, and regret. While some critics have argued that the bare-bones story creates a tensionless void at the film’s heart, it could also be said that by purposefully paring the story back, Coppola allows the emotional truths of the film to hit harder.

The tension lies less in the will-they-won’t-they plot, and more in the seemingly incongruous juxtaposition of two very different styles: narrative simplicity and extravagant presentation. The couple, now separated, embark on their own journeys over the course of a night. What could appear banal—they each undertake a brief fling with someone they’ve just met—is enlivened by wildly romantic expression.

The emotional lives of Hank and Frannie are expressed through almost continuous song, courtesy of Tom Waits, who wrote and recorded every song on the film’s soundtrack with Crystal Gayle. By 1981, Waits had established himself as a musical storyteller of the highest order. Albums like Small Change and, my personal favourite, The Heart of Saturday Night, saw the troubadour pouring out noir-ish tales of drunken brawls, terrible hangovers, and failed romances over his piano, his trademark gin-soaked baritone blending into the smoke and chatter of bars and clubs.

Beneath the bitterness and occasional violence, there’s an intrinsic romanticism to Waits’ lyrics and a cinematic quality to his blues-tinged arrangements. Combined, the result is something more than just a soundtrack. The music is etched into the film, like grooves on a record, creating a symbiotic relationship between the two that is inseparable. The music becomes the film, and the film becomes the music.

Perhaps more importantly, the songs are musical embodiments of both Hank and Frannie. Crystal Gale, on behalf of Frannie, ponders, “Is there any way out of this dream?” Later, in a spoken-word section, Waits appears to literally narrate Hank’s thoughts. The result is a hybrid musical, a film that takes old forms and incorporates them into something that feels new and hard to define.

Depending on whom you ask, One From the Heart is either an indisputable musical or it’s not one at all. Perhaps it’s this elusiveness that led to critical frustration in 1982. However, it can now be seen as a testament to the film’s sense of individuality that it is neither one nor the other. If Frannie and Hank can’t make up their minds about what they are, then why should the film?

It’s Coppola’s embrace of contradictions that truly makes the film sing. Frannie yearns for freedom, but she also desires to feel loved and wanted by another man. This takes the form of Ray (Raul Julia), a suave lounge singer who moonlights as a waiter in the same restaurant where he sings. In one sequence, the flirtatious pair tango to the music of an invisible band, silhouetted

Frannie yearns for freedom, but is the Tango a dance of liberation, or is it one of further entrapment? Meanwhile, Hank—who supposedly craves domestic stability that Frannie can’t offer him—ends the night with a circus performer called Leila (Nastassja Kinski). She uses a telephone wire as a tightrope, and claims that “if you want to get rid of a circus girl, all you’ve got to do is close your eyes”. Coppola here tugs at the contradictions. A woman who desires freedom entwining herself with another man, and a man who desires security spending the night with a woman who could vanish in a puff of smoke at any moment.

Very few people are fortunate enough to know unequivocally what they want in life. Even fewer are fortunate enough to know what they want and have it remain unchanged over the years. Relationships can only become more complex and thorny when one takes these questions into serious consideration. You can either refuse the question entirely and maintain order, or contemplate the question in the hope of finding your truest self, and risk significant upheaval in the process.

People aren’t binary—we often find ourselves on a spectrum of wants and desires, yearning for a place to call home, while also craving complete liberation from it.

One From the Heart is a kind of Rumspringa, where an alternative life can be experienced before a decision must be made to return home or take flight to foreign lands.

It’s also a funny kind of riff on It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), but while Frank Capra was fairly resolute about the nobility of sacrificing one’s dreams, Coppola’s film ponders the potential cowardice in turning back and travelling the old, familiar road.

It’s particularly noteworthy that One From the Heart marked a dramatic departure for Coppola. Perhaps he too was contemplating the path not taken, and the road that lay ahead for him. Perhaps by experiencing the chaos and trauma of making Apocalypse Now, he found himself yearning for a return to something controllable, classical, and ultimately more humane.

The stakes appeared lower, but the colossal financial failure of One From the Heart effectively ruined American Zoetrope in the 1980s. It was an expensive gamble, and whether it’s considered a success or not depends on whether you view money or artistic merit as the markers of success.

Both One From the Heart and the new Reprise cut depict Francis Ford Coppola as a character from a Tom Waits song: a dreamer haunted by the perceived failures of his past. However, unlike the protagonists of Waits’s songs who often end up empty-handed, Coppola has ultimately found something valuable.

It’s absolutely essential that cinema is comprised of artists willing to experiment with both how films are produced and the form they take. Coppola’s experiment may finally be seen as the achievement it is now, in the same way that his later Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) has undergone re-appraisal in recent years. Reworking an earlier film may, in some circumstances, be tinkering with perfection, but it can also be a way to re-present a film as a living, evolving entity.

After all, if our relationships with the films we love can change and grow over the years, then why shouldn’t this take a literal form with Reprise? It’s certainly preferable to have Coppola tinkering with his own work now than, say, a distributor decades down the line.

We may always be searching for our ever-changing definition of perfection, constantly attaining what we want before recalling some other dream from long ago, whispering to us now like a voice in the night. One From the Heart suggests that we can always change. Whether or not we change back is simply a roll of the dice.

USA | 1982 | 107 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • GERMAN

This new 4K restoration is utterly sublime. The film is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio, and everything within the frame appears incredibly vibrant. Original camera negatives provide a surprisingly clear image throughout, and the restoration maintains natural sharpness in most scenes, while a pleasingly intentional softness is retained in others. The lighting throughout the film is spellbinding, and everything from a bedside lamp with a shirt draped over it to the warm orange glow of a billboard looks beautiful in this release.

The version of Reprise that I watched had an English 2.0 LPCM Stereo soundtrack, which provided depth and clarity particularly in the soundtrack, but felt a little unevenly mixed when compared with the much quieter dialogue. This would likely not be an issue with a surround sound set up, and the 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack.

The sound mixing is far from a deal-breaker—it just had me fiddling with the volume every now and then. Overall, this is a luxurious restoration, and the best way to see the film outside of a cinema screening.

director: Francis Ford Coppola.

writers: Armyan Bernstein & Francis Ford Coppola (story by Armyan Bernstein).

starring: Frederic Forrest, Teri Garr, Raul Julia, Nastassja Kinski, Lainie Kazan & Harry Dean Stanton.