OLDBOY (2003)

After being kidnapped and imprisoned for 15 years, Oh Dae-Su is released, only to find that he must find his captor in five days.

After being kidnapped and imprisoned for 15 years, Oh Dae-Su is released, only to find that he must find his captor in five days.

As South Korea moved from an authoritarian state to a burgeoning democracy, Korean cinema experienced a renaissance. Contemporary classics such as Shiri (1999) and Peppermint Candy (1999) injected new life into ‘New Korean Cinema’. At the turn of the millennium, a new generation of directors began exploring darker themes and genres during what became known as the ‘Korean New Wave’. Ambitious filmmakers including Bong Joon-ho (Parasite) and Kim Jae-woon (A Tale of Two Sisters) sought to bridge the gap between commerciality and aesthetics.

Korean cinema was revitalised in 2003 with Park Chan-wook’s thriller Oldboy / Oldebui / 올드보이. Receiving enthusiastic support from Quentin Tarantino, Park won the ‘Grand Jury Award’ at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival. Proceeded by the critically acclaimed Sympathy for Mr Vengeance (2002) and followed by Sympathy for Lady Vengeance (2005), Oldboy is the second instalment of the filmmakers ‘Vengeance Trilogy’. Based on the Japanese manga by Garon Tsuchiya and Nobuaki Minegishi, Park earned international acclaim and inspired global interest in Korean filmmaking. While The Handmaiden (2016) remains Park’s biggest international success, Oldboy undoubtedly put the filmmaker on the map.

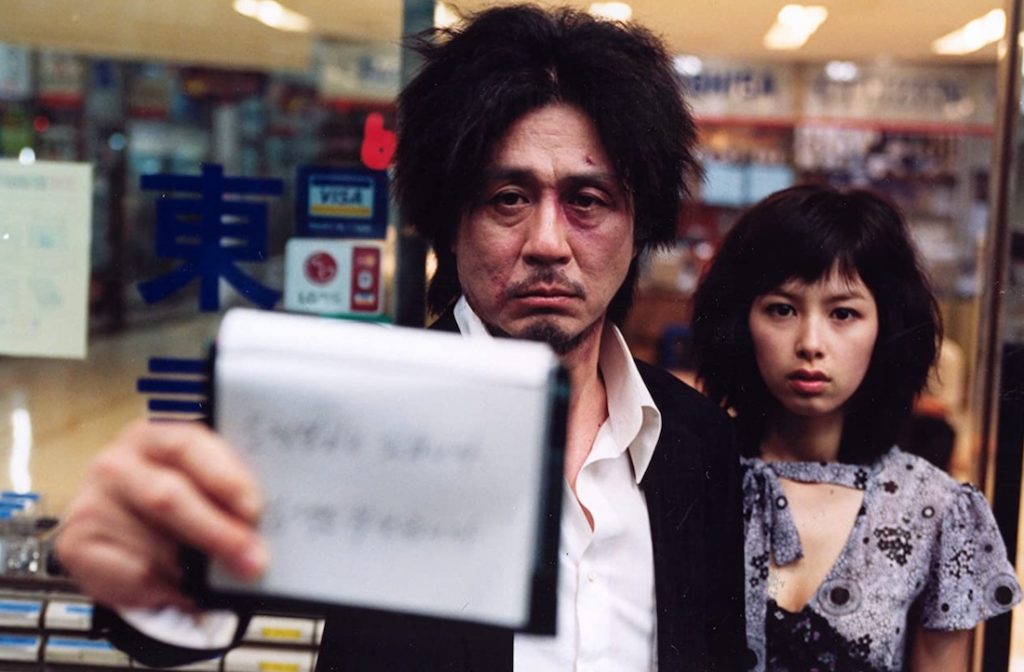

One rainy evening, after being released from a police station, businessman Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik) is mysteriously kidnapped. When he regains consciousness he finds he’s trapped inside a sealed hotel room. With a television broadcasting outside events and a routine serving of fried dumplings, he’s held captive in this room for 15 years. And during his mysterious incarceration, his kidnapper assassinates Dae-su’s wife and plants evidence to incriminate him. Then, after unexpectedly waking up in the outside world, the freed Dae-su learns that his terrible ordeal is far from over. A twisted game is still being orchestrated by his unknown tormentor. Driven by a fierce determination, Dae-su sets out to track down his oppressor, befriending a beautiful young chef named Mi-do (Kang Hye-jung) at a sushi restaurant who agrees to help him. However, they soon learn that Dae-su’s not the only one with revenge on his mind…

The casting of Choi Min-sik is perfect as the unpredictable and complicated Dae-su. His weathered looks and emotional volatility earned him acclaim in features including Swiri (1999) and Failan (2001). The actor gives an excellent performance and it’s difficult to imagine anyone else playing this character. We first meet him as an unsympathetic drunk, howling profanities in a police station, then when he emerges from his bizarre captivity we follow Dae-su’s attempts to learn the reason behind his long imprisonment. The character requires a specific emotional duality and Choi perfectly portrays Dae-su’s disconnect with the outside world. There are several scenes as he smiles where we sense of the inner pain boiling beneath the surface. Within seconds he switches from calm and comedic to a deranged beastly agent of violence. In possibly the actor’s most recognisable role, he commands attention in ever scene. Truly embodying the character with grace, charisma, and rigour, he provides a kinetic personality akin to Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver (1976). It’s a complex performance but, no matter how radical his actions become, the character never loses our sympathy.

Caught in the middle of this duelling tale of vengeance is the beautiful Kang Hye-jeong (Sympathy for Lady Vengeance) as the Mi-do. She’s simultaneously endearing and innocent, preventing Dae-su from spiralling into madness. Hye-jeong portrays her character’s sweet naiveté to perfection, providing an excellent contrast to the melancholy madness of Dae-su. She exhibits convincing chemistry with her counterpart, creating a tender and nuanced relationship. Additionally, Yoo Ji-tae (Ditto) gives a convincing and multilayered performance as Lee Woo-jin; played with bravado, the sophisticated businessman is shrouded with a mysterious aura. Beneath his composed exterior remains a cold malevolence of a man driven with revenge towards Dae-su. Although he remains an enigma until the third act, he provides an incredible adversary. Admittedly, the casting of Ji-tae may seem like an odd choice as he’s 14 years younger than Choi. However, providing Dae-su’s ordeal, it’s understandable why Woo-jin retains his youthful appearance.

Park Chan-wook’s masterful direction rightly ascended him to a new level of fame. Although Oldboy has a similar aesthetic to Sympathy for Mr Vengeance, the director here refines his artistic style. The heavily stylised filmmaking is almost operatic in its approach, and his visual style could easily be compared to Quentin Tarantino. However, comparisons to Terry Gilliam’s Twelve Monkeys (1995) might also be made. Park meticulously uses interesting and unique framing, capturing scenes with dutch angles and frequent overhead panning shots. With a runtime of 120-minutes, the director retains a dark style that so brilliantly captures the uncompromising harsh atmosphere. As Dae-su becomes the detective of his own story, Oldboy leans heavily into a neo-noir vibe. The colour saturation and unforgiving dreamlike world manipulate the captivating narrative. Although Park perfectly crafts a revenge thriller, his inventiveness lets different genres blend into each other with ease. Successfully creating a furiously paced mystery that barely gives on time to breathe.

Over the years Oldboy‘s been misinterpreted as a disturbing example of exploitation cinema. Admittedly, several sequences will traumatise even the most hardened viewers, but the level of bloodshed is far below that of Ichi the Killer (2001) and suchlike. As Park stated, “I try not to portray violence in a beautiful way… I feel conscious of guilt”. For exploitation enthusiasts, Oldboy can be hailed as an arthouse-style homage to the genre. One particular sequence involves the forcible removal of teeth rivals Laurence Olivier’s Nazi dentist in Marathon Man (1976). Another involves a pair of scissors to evoke Takashi Miike’s Audition (1999). While tapping into the innermost discomforts of violence, Park certainly pushes the boundaries of censorship. However, the director avoids glorifying the content and swerves violence with creativity and imagination. We’ll see the hammer clasp on to a guard’s incisor like a nail before a cutaway reveals a collection of removed teeth. Although it’s heavily stylised, it doesn’t detract from the genuine revulsion of these scenes.

Amongst the grime, beauty can be found in almost every corner of each composition. The sharp-angled cinematography by Chung Chung-hoon (Zombieland: Double Tap) is extraordinarily framed. Certain sequences are illustrated so artistically, it feels like they’ve been lifted from the manga it was influenced by. A highlight is the infamous one-take fight sequence between Dae-su and dozens of thugs. Captured entirely from a two-dimensional perspective, the camera pans down a hallway following the action. As Dae-su knocks down goons with his hammer, he barely flinches as wooden beams shatter over his beaten body. His rage is so great that he’s scarcely slowed by the knife impaled between his shoulder blades. Howling in pain as each weapon connects, one feels it rattle through your own bones. It’s utterly breathtaking to watch him charge at his opponents, growling with his weapon to hand. It’s an image that’s become synonymous with the film. The outcome is an intoxicating choreographed traditional piece of stunt work, that genuinely feels realistic.

Refreshingly, Oldboy is far less pastoral than many of its prestigious South Korean counterparts, such as Peppermint Candy (1999) and Memories Of Murder (2003). Ryu Seong-hie’s (The Host) production design derives plenty of inspiration from the wonderful New York urban hellscape featured in movies from the 1970s and 1980s. The streets of South Korea are drenched in neon light, edged with a nightmarish quality, while the grimy interiors provide a nice backbone for the intermittent grotesque sequences that occur, such as one disturbing scene featuring ants. The apartment Dae-su is imprisoned in is filled with a sickening colour scheme and hellish “inspirational” painting that would drive anyone insane. The colours and setting simultaneously contrast and complement each other, creating harmonious conflicts much like the thematic and narrative elements. All of these choices flow cohesively projecting a sense of realism in what is essentially a very surreal environment.

Those familiar with Park’s filmography would argue his unique interpretation of violence, guilt, and redemption are influenced by his philosophical worldview. On the surface, Oldboy may appear to be a thrilling story of revenge. However, upon repeat viewings, there are rich subtexts that can be traced back to Greek drama. In the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex, a king learns that a plague in his city has been caused due to his past actions, ultimately leading him to fulfil his prophecy of murdering his father and forming an incestuous relationship with his mother. Park leans into these elements, violently spinning a narrative that twists and turns as the layers are revealed. We gradually learn why Dae-su was kidnapped through Kim Sang-beom’s (The Handmaiden) incredible editing. Similar to Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000) we jump between narratives revealing fragments of the story. Eventually culminating in a spectacular climax that would put M. Night. Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense (1999) to shame. As we realise why he’s been imprisoned, we gain an understanding of his own part in the chain of events.

At the beginning we’re shown the proverb “Be it a grain of sand or a rock, in water they sink the same”. As with the butterfly effect, it highlights how actions of the past can have detrimental consequences on the present. Park challenges the audience to see the denial of one’s transcendent ideals. We are constantly convincing ourselves to realities in order to justify and validate our actions. Although Dae-su’s flawed, he’s still human and doesn’t deserve the fate he’s been committed to. The prominent quote “Even though I’m no better than a beast, don’t I have the right to live?” reoccurs frequently. The director is questioning whether those who have done wrong truly deserve the punishments inflicted upon them. When the credits roll, our feelings towards Dae-su are confused and traumatised. Has he finally gained redemption or is he blissfully unaware of his discriminatory actions? Admittedly, some viewers may find the ambiguous ending unsatisfying. However, one would argue therein lies the beauty of Oldboy. It’s the perfect denouement to a tale of revenge, sorrow, and regret.

Unfortunately, Oldboy wasn’t without controversy upon release. Many western audiences were outraged with the infamous scene involving a live octopus being consumed on camera. Many detractors declared this as animal cruelty. However, in eastern cultures, if served with pickled ginger it’s known as sashimi. Although I’m not condoning this stylistic choice, Frances Ford Coppola never received such indignation for Apocalypse Now (1979)! One would argue Park’s choice of using such gut-wrenching imagery is the use of foreshadowing. The ultra-violent and sadomasochistic torture metaphorically enhances the Dae-su’s twisted emotional narrative. Regardless, the disquieting use of violence didn’t affect Oldboy’s theatrical run. In South Korea, it became the fifth highest-grossing film of 2003, earning a total of $14M worldwide.

Having rewatched Oldboy several times now, it remains one of the finest vengeance stories in modern cinema. It’s an incredible piece of filmmaking that explores the darker side of man’s righteous quest for retribution. Choi Min-sik gives a career-defining performance and Park Chan-wook demonstrates his talent as a director. Park’s visceral storytelling is captivating and unpredictable, but above all else is his mastery of the visual medium. Despite being wildly entertaining and brimming with creativity, several themes explored may traumatise most viewers. However, if one can look past the surface, the wealth of the story heightens.

If you enjoyed reading this review and would like to support my writing, then please buy me a coffee.

SOUTH KOREA | 2003 | 120 MINUTES | 2:35:1 | COLOUR | KOREAN

Utilising the original theatrical aspect ratio of 2:35:1, Oldboy showcases a dazzling 4K restoration courtesy of Arrow Video. The 2160p Ultra HD image has been transferred from the original film negatives and was supervised by Park himself. Considering this is only Arrow’s sixth 4K release, they’ve done a wonderful job with the image.

Perhaps the most striking aspect is the vibrant colour palette that creates some stunning tones. The opening sequence featuring a purple umbrella and green grass during a dream sequence leap from the screen. Contrast levels remain consistent although there’s a noticeable fluctuation during flashback sequences. However, considering this transfer was supervised by the director one can only assume these are intentional. Additionally, blacks remain inky and retaining clarity and detail that was lost on previous releases. This new transfer boasts phenomenal fine detail that puts my previous Tartan Video release to shame! Finer details such as wrinkles and facial pores are evident during close-ups, whereas every strand of Dae-su’s distinctive hair is visible. The healthy grain may disgruntle several cinephiles but overall the picture is superb throughout.

The 4K Ultra HD release of Oldboy features several audio tracks with optional English subtitles. Unfortunately, the Korean 7.1 Dolby Digital-Ex mix featured on previous releases is missing. However, the 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio and LPCM 2.0 stereo are available. Additionally, Arrow offers an optional English 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio and LPCM 2.0 stereo for fans of dubbed tracks. As someone who isn’t a massive advocate of dubbed tracks, this review will mainly focus on the Korean audio options. Dialogue is crisp and clean throughout, with Dae-su’s internal narration receiving prioritisation surrounding the rear channels.

However, Jo Weong-wook’s hauntingly beautiful score is easily the high point of the presentation. His soaring strings and lofty orchestral melodies sweep the soundstage, defining key moments. The subwoofer picks up the bone-crunching impacts of fists and hammers, increasing the intensity of each violent sequence. Exterior sounds establish a constant presence, utilising the rear channels to full effect. The bustling streets of South Korea are aggressively clear and heavy footfall and traffic noises create an immersive atmosphere.

director: Park Chan-wook.

writers: Park Chan-wook, Lim Joon-Hyung & Hwang Jo-Yun (based on the graphic novel by Nobuaki Minegishi).

starring: Choi Min-Sik, Kang Hye-Jeong, Yoo Ji-Tae.