NIGHTBREED (1990)

A troubled young man is drawn to a mythical place called Midian where a variety of friendly monsters are hiding from humanity. Meanwhile, a sadistic serial killer is looking for a patsy...

A troubled young man is drawn to a mythical place called Midian where a variety of friendly monsters are hiding from humanity. Meanwhile, a sadistic serial killer is looking for a patsy...

Nightbreed is an unusual mix of horror sub-genres and a notable chapter in the history of ‘cinema fantastique’. It’s a monster movie if ever there was one, but it’s really about ‘the others’ in society, sub-cultures, and tribes. So it’s heartening that, although the heavily cut theatrical release was a disaster, Nightbreed nevertheless found a devout cult following that’s kept it alive. A quarter-century later (after several unofficial fan-edits circulated at conventions) it’s those fans who were instrumental in bringing Clive Barker’s original vision to the screen.

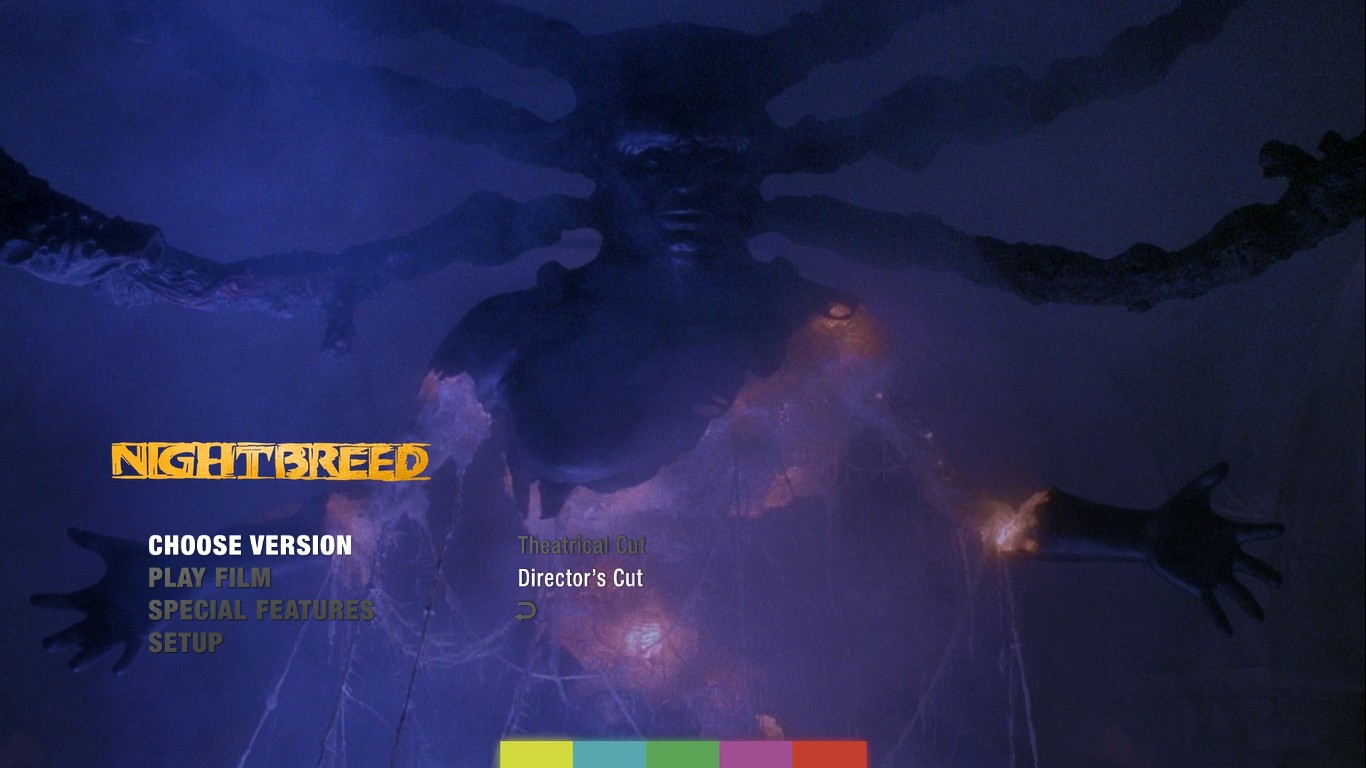

In 2014, after hundreds of reels of discarded scenes and unused footage were tracked down to a vault in Ohio, USA, Scream Factory released a reassembled and digitally restored version that was faithful to Clive Barker’s screenplay and storyboards. This 120-minute Director’s Cut has now been released in Europe through Arrow Video on Blu-ray, remastered from the original camera negative and with a burgeoning package of extras. The 2-disc Collectors’ Edition also includes the 102-minute theatrical cut, transferred from the original interpositive. They’re two very different films and now audiences can compare and contrast, to decide where it all went wrong.

Nightbreed, based on Barker’s 1988 novella Cabal, was the English author’s fifth screenplay to be produced, but only his second film as director. His directorial debut was Hellraiser (1987), which marked the resurgence of British horror cinema. But whereas Hellraiser had been a surprise success redefining the genre and pulling in $14M at the box office on a £1M budget, Nightbreed cost around $11m and grossed a little under $9M.

It was a painful experience for all involved and damaged Barker on both a professional and personal level. It would be five years until he sat in the director’s chair again with Lord of Illusions (1995) and what started as a three-picture deal ended there. He walked away from directing to instead focus on writing and producing.

It seems the studio executives at Morgan Creek and the marketing team at 20th Century Fox distribution just couldn’t wrap their heads around what Nightbreed was. Although the 1980s were over, the studio wanted yet another slasher film. A horror movie. They wanted gore! They wanted scary monsters! Instead, they got super freaks.

What they failed to see is that, although Clive Barker’s roots run deep into horror heritage, he isn’t your standard horror writer. He was the world’s foremost ‘fabulist’ (a genre he created for himself that he says stems from folklore, fairy-tales, and scripture), hence the many Biblical parallels in Nightbreed. It’s a genre that’s since gone mainstream.

Today, the reception would doubtless be different. Audiences are used to the idea of a cinematic universe where freaks, mutants, and monsters can be the good guys. X-Men and the Twilight saga spring readily to mind, but also important TV series like Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) that paved the way for the likes of Heroes (2006-10), Being Human (2008-13), and more recently Neil Gaiman’s American Gods.

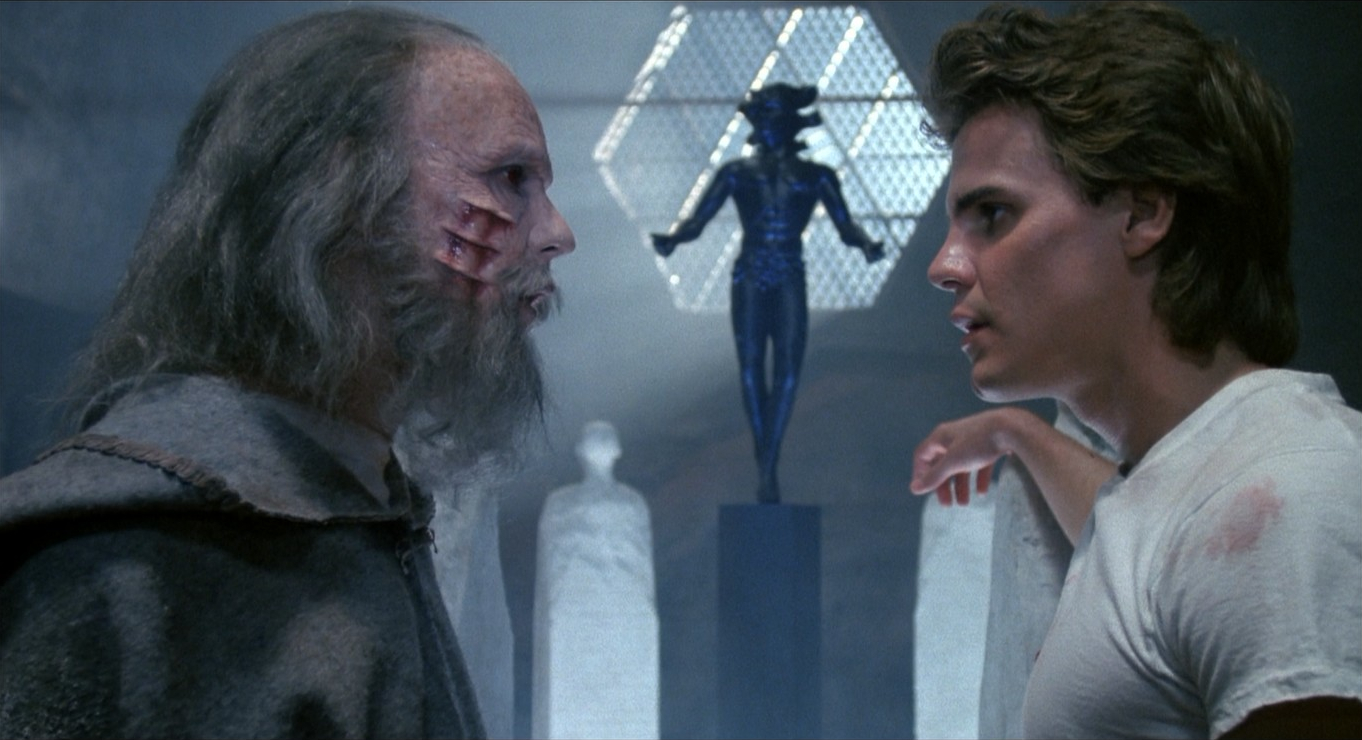

Nightbreed tells, at its heart, the origin story of a character who becomes Cabal—a sort of Messiah for the oppressed and displaced monsters who hide in an underground city beneath the fabulous necropolis of Midian. But we don’t know that when we meet Aaron Boone (Craig Sheffer), a troubled metal-shop welder who’s grown used to his disturbing dreams of monsters. He’s been seeking help from Dr Philip Decker (David Cronenberg), who’s drawn parallels between some of Boone’s dreams and the work of a serial killer who murders families in their homes. With the help of the drugs he’s been prescribing, the psychotherapist makes Boone believe he’s guilty and needs to give himself up to the police.

Instead, goes to see his girlfriend Lori (Anne Bobby) one last time as she sings at a nearby bar (belting out a raunchy version of the 1960s hit song “Johnny Get Angry”), then he attempts suicide-by-truck. He fails and as he regains consciousness in hospital he overhears another patient, the seemingly insane Narcisse (Hugh Ross), ranting about a place called Midian where the monsters live.

I’m trying to avoid too many spoilers here, but some of those reading this review, who think they’ve already seen Nightbreed, may well be thinking “hang on, I don’t remember all that.” That’ll be because I’m talking about the Director’s Cut—the proper version and not the 1990 theatrical release. I hadn’t seen this long-lost definitive version, either. So, like many, I’d dismissed the film as an unremarkable yet entertaining piece of hokum that didn’t hang together. A big disappointment after the promise of Hellraiser… but the Director’s Cut is not that film.

Both versions retain a lot of retinal pleasures—that’s to say they provide a spectacle. But obviously there’s even more of Barker’s visual flair in the Director’s Cut. He uses the camera in a painterly fashion—placing objects in the foreground, and shooting through windows, flames, or blurred crowds. He could clearly handle a cast and crew too. All the performances are fine, often better than they need to be, with Cronenberg stealing the show with his chillingly subdued psychopath Decker…

The fame of Clive Barker has grown and grown, from the first cult readership of his Books of Blood short stories in 1984 (praised by Stephen King as “the future of horror”) to the world-wide audience that keep his epic novels in the international best-seller charts for months. Barker made his presence felt in the US, rapidly earning himself a degree of notoriety and infamy with Hellraiser. Surprisingly, though, it was Nightbreed that completely baffled test audiences and stirred up plenty of trouble with the MPAA, the American equivalent of the BBFC (British Board of Film Censors).

I recall first interviewing Barker whilst he was promoting Nightbreed and even back then it was clear he hadn’t managed to get the film he wanted onto the screen. I felt he was promoting the studio’s re-hash under duress. He explained part of the problem:

They gave us seventeen scenes they wanted cut from Nightbreed… I got four Xs on the movie, and I only got one on Hellraiser. Which is bizarre to my mind because the movie is a much mellower and less aggressively horrible movie than Hellraiser. Well, both movies are fairy tales.

Barker was contracted to deliver an R-rated movie and ‘Xs’ refer to content that would mean a film would not be granted a certificate. Barker lamented:

What can you say—they’re inconsistent. That’s the nature of the censorship game: you never know where they’re going to come from. They’re always going to find something, that you don’t think twice about, bothers them in an incredibly weird way and then something that you think is really gonna cause trouble, they just pass over. There’s no logic or pattern to it and that’s very irritating. You’re dealing with irrational people.

Interestingly, he’d cast David Cronenberg in a central role as Decker, who’s also behind the mask of the terrifying ‘buttonface’. So, I asked him, as a relative ‘newbie’ director, what it was like dealing with a notable horror director and one of his heroes?

Wonderful, a deeply rational man! He’s someone whose enthusiasm for the genre is not dissimilar to mine in the sense that we both feel that you can do things with the genre which are more than saying ‘Boo’ behind people’s backs. I’ve never been interested in ‘Boo’ pictures, and David isn’t either. You don’t go to one of David’s movies to be made to jump, you get something different, a kind of intelligence and poetry which is missing in most horror movies.

A central motif in Nightbreed is finding truths about yourself within dreams and it’s from his dream diary that Clive Barker plucked many of his recurring ideas and themes. His dreams become his drawings, stories, novels, films, and then seep into our memories and nightmares.

My college degree thesis explored the many parallels between the state of dreaming and watching a movie in a darkened auditorium. It put forward the idea that the flickering light of the screen is our modern substitute for the flickering flames of the fire, and celluloid film is our method of dream-sharing. Ever since the first groups of humans huddled around the first fires, the Shaman has been with us. The wise man, a storyteller recounting his dreams, tales of spirits and animals that live in the Otherworld. His dreams would become the dreams of the tribe, their identity. I was interested to know if Barker aligned himself at all with the Shaman?

Clive Barker is an intelligent writer and a deep thinker, throwing such a question his way didn’t phase him in the slightest as he pondered at length…

The whole idea of the shamanistic principle, that the tribe can collectively dream a solution to a problem and that the shaman somehow indicates the direction in which the tribe heads off into their collective unconscious, to pick around amongst the bones of old gods and return with news and indications… that is very easily parallel with what, particularly the writer of the fantastique is doing.

The writer of naturalist fiction is necessarily bound, by definition. The fantasist says, all right, I can write about divinity, semi-divinity, demons, gods and spirits of air and water or stone. I can write about human beings, sane, crazed, visionary, even dead and I can write about them all in landscapes that are very realistic or very unrealistic. I can write about them in states of mind which are also worlds unto themselves.

So, when you’ve got that range of possibilities, reality dissolves, which I think is a dream state in a way because in our dreams we also meet the dead, we commune with gods and spirits. Whether we literally do that is an issue which I haven’t resolved for myself. I’m tempted to think that sometimes we do, that there is a literal sense in which in certain states of consciousness, dreaming, trance states, drug states, any altered states, I think it’s very possible that in some instances we are actually communicating with entities other than human, at least other than living human.

But even putting aside that possibility—which I realise marks me as a crazy—let’s just assume that this is all the mind’s creation. Even under those circumstances, in dreams we are learning from our subconscious, which is, to take the realist view, representing itself as the dead or the semi-divinities in order to instruct us. We are learning from those forms and forces in symbolic form, and we are growing by the exchange.

That’s the kind of place Nightbreed was coming from, so it really wasn’t a surprise the studio executives didn’t get it. They ended up causing him far more trouble than the censors! The first alarm bells started ringing for Barker when one of the marketing team at 20th Century Fox came and told him he needed to rework the narrative because there was a danger the audience would identify, or at least sympathise, with the monsters! Of course, that’s the whole point of the film.

Here, the monstrous is something from within. The true ‘monsters’ in Nightbreed are the humans: the small-town redneck cops, the zealous preacher, the manipulative psychotherapist, etc. All figures who take it upon themselves to judge others. The so-called monsters (those in prosthetics) are the others, the oppressed, the harassed, the displaced, the stigmatised minorities and those who live an alternative lifestyle.

Barker himself is openly gay and it becomes significant when you consider that HIV and AIDS had only been identified a few years earlier, in the mid-1980s and, through poor judgement, had been branded ‘the gay plague’ in the media. This led to widespread fear of anyone who lived a lifestyle associated with homosexuality.

There’s no doubt the scene where Ohnaka (Simon Bamford) is dragged from Midian and beaten by police is intended to strike a resonance with ‘gay-bashing’. He does have tattoos and piercings, which were nowhere near as fashionable back then as they may be now, but has no monstrous attributes. It’s still a difficult scene to watch, as a gentle human being, who puts up no resistance, is treated with contempt for being different and finally destroyed by sunlight. One certainly sympathises with the ‘monster’.

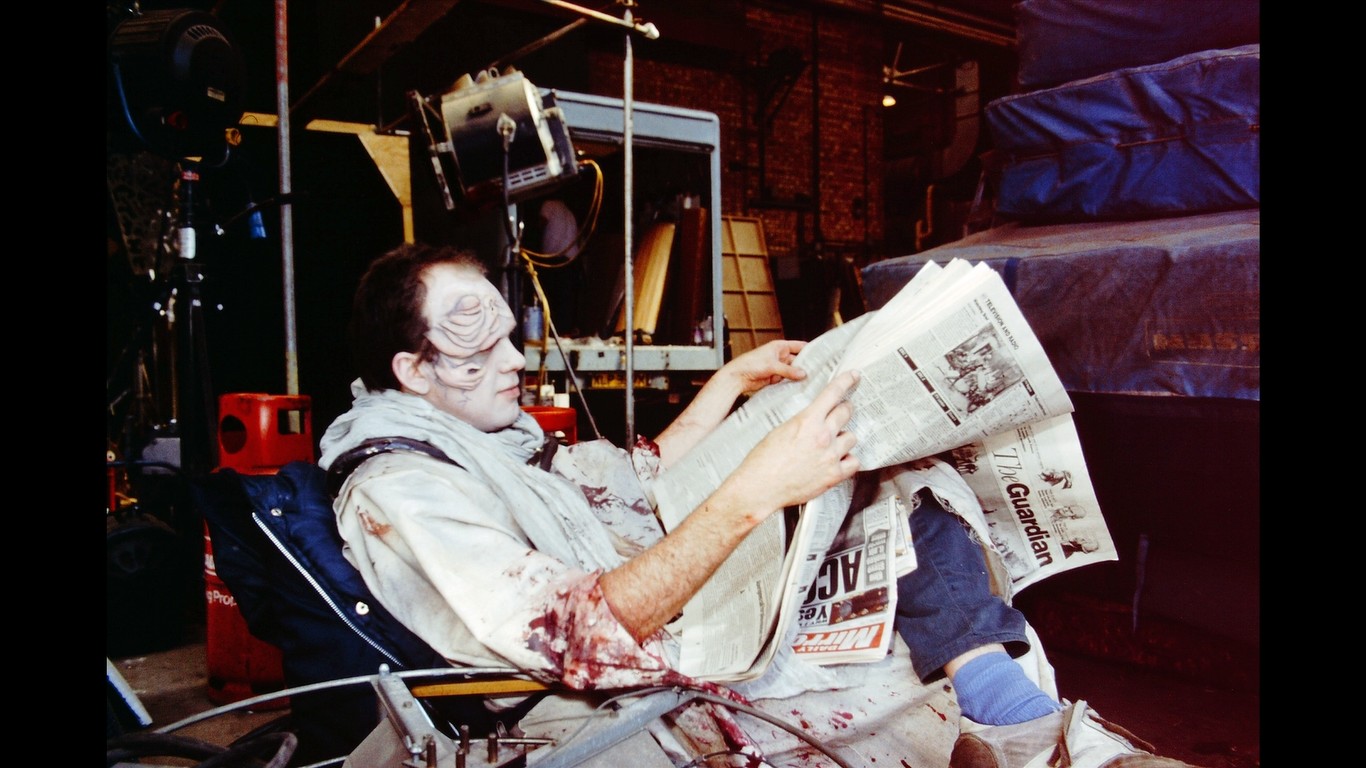

Not that the monsters of Midian are all gentle and good. Some are dangerous with frighteningly primal powers. Some are recognisable as vampires and werewolves, many look like they’re suffering some sort of disability, others are weird and wonderful inventions from the mind of Barker, concept artists Ralph McQuarrie, and a hard-working special effects team lead by Bob Keene. At the time, Nightbreed was recognised as having the greatest number of actors in prosthetics on any shoot in cinema history, with 300 different make-up jobs in the final apocalyptic showdown.

At the time that was some achievement. Unfortunately, this is also a major flaw of the film because the prosthetics are somewhat dated and don’t hold up to scrutiny today. That said, the make-up effects are tremendously inventive and for the most part the key character designs are effective enough. Especially the likes of Peloquin (Oliver Parker) and Lylesberg (Doug Bradley), incidentally both played by actors who had appeared as Cenobites in Hellraiser—and, of course, fan-favourite Shuna Sassi (Christine McCorkindale) the ‘sexy’ porcupine lady…

Some cineastes, myself included, will relish the restored feature as a showcase of those amazing practical effects of bygone days. The Doctor Who standard monsters, the rickety stop motion, and the absolutely gorgeous matte paintings by VFX veteran Cliff Culley, that also combined some miniature effects. There’s a very distinctive and organic feel to the visuals throughout that just isn’t present in modern CGI. So, if you think of it as a sort of exhibition, all those elements enhance rather than spoil the final outcome. And it’s great to finally see many of these in action as a vast number were cut out of the theatrical release…

After a disastrous test screening, to an audience sold on a slasher movie, studio executives at Morgan Creek stepped in and took control of the final film from Clive Barker. They brought in Mark Goldblatt, who had edited The Howling (1981), The Terminator (1984), and Commando (1985), to turn Nightbreed into an action movie. Barker was instructed to shoot additional scenes that upped the gore quotient and placed more emphasis on certain characters.

They pressured him into writing a different ending, resurrecting some characters who died heroically in the original script and discarding others entirely. The worst of it was that they decided that elements such as story and plot development just slowed things down too much and 20-minutes were excised from the first act that set-up central characters to reveal their motivations. Sure, things moved along a lot quicker, but all at the expense of making any sense! Strange thing is, for me, the Director’s Cut doesn’t seem to drag at all, even though there are about 40-minutes restored to it. I guess that’s called pacing! And Barker’s original ending is just so much more meaningful and poetic.

Despite the additional shooting and re-editing, Nightbreed still performed poorly at the box office. Two video games followed quickly in an attempt to capitalise on the film’s promotion, but those are more like electronic versions of roleplaying adventure books than the gaming we’re now used to.

But the characters did live again in a series of comics. In 1990, Epic Comics produced a four-issue adaptation of the film, which more closely followed Barker’s original script. The comics proved popular enough to continue into a 25-issue sequence that took the story beyond the end of the movie. A tie-in book called Clive Barker’s Nightbreed Chronicles provided a pictorial reference that showcased the monsters and their inventive make-up. Hellraiser vs Nightbreed: Jihad, a graphic novel, followed in 1991. It does what the title suggests and brings together the two worlds, pitting the Cenobites against the Nightbreed.

This spattering of spin-off material was not enough to keep fans entirely satisfied and through the convention circuit a movement calling itself ‘Occupy Midian’ grew. Its members were hellbent on finding the lost footage of Barker’s original so they could see just what he’d intended. This eventually resulted in a fan edit known as Nightbreed: The Cabal Cut that spliced-in really poor-quality VHS clips of missing footage.

It was this that inspired Mark Miller of Clive Barker’s production company, Seraphim Inc., to tenaciously follow all leads in trying to track down the missing film reels of this material. As Scream Factory was planning on releasing a digitally cleaned-up version of the Cabal Cut, which still would have been rather ropy, one of the releasing company’s contacts put him onto a storage warehouse in Ohio that used to archive film stock around the time that Nightbreed had been made. This was the jackpot he’d been looking for and 16 hours of lost footage was digitally remastered so that, finally, a Director’s Cut could be reassembled!

Even better news for those faithful fans: a Nightbreed TV series is currently in development and Clive Barker appears to be enjoying a sudden renaissance with reboots of Hellraiser and Candyman (1992) in the offing.

writer & director: Clive Barker.

starring: Craig Sheffer, Anne Bobby, David Cronenberg & Charles Haid.