MOTHRA (1961)

A giant, ancient moth attacks Japan when trying to rescue its two petite worshippers, who were taken by an unscrupulous showman.

A giant, ancient moth attacks Japan when trying to rescue its two petite worshippers, who were taken by an unscrupulous showman.

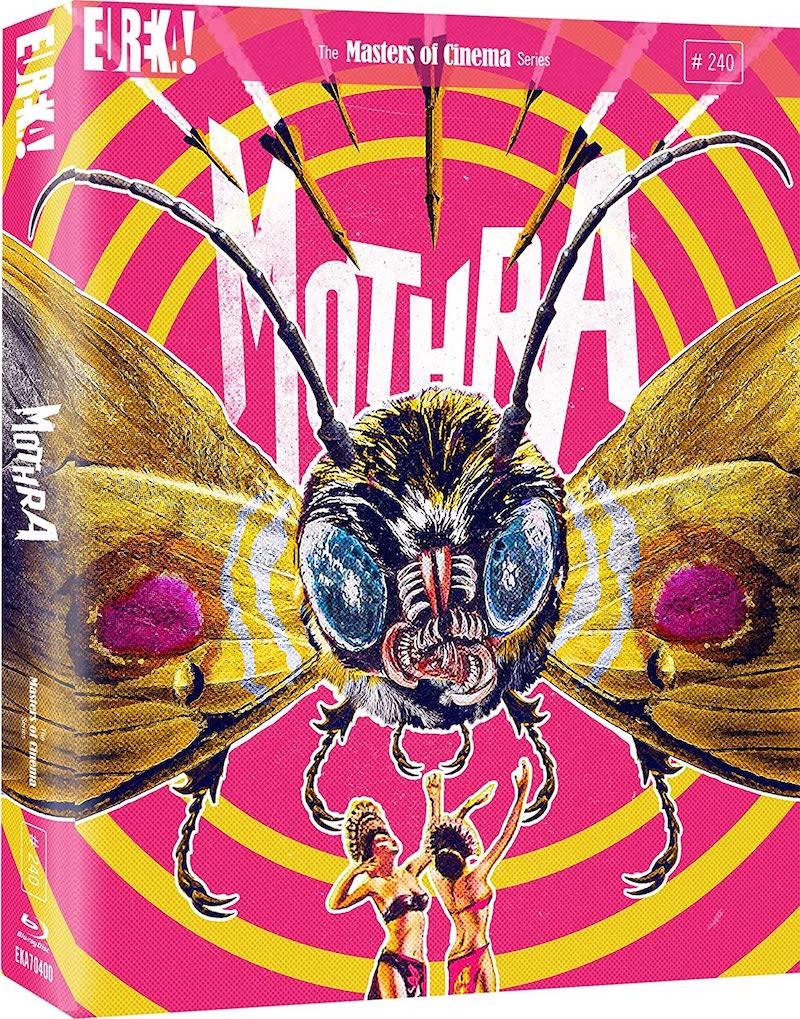

If you’re interested enough to be reading this review, you probably don’t need to. I’m guessing you already love Mothra and are super-excited about Eureka Entertainment’s new Limited Edition Blu-ray, another welcome addition to their Masters of Cinema imprint. And what a handsome package they’ve put together! The artwork alone will send a thrill of nostalgia through all fans of kaiju films—a distinctive genre of Japanese monster movies, of which Mothra is second to none.

That the two versions included on the Blu-ray haven’t been remastered from a new scan is going to disappoint some. Not me, though. I often feel the digital clean-ups change the whole vibe of classic films and love seeing some gorgeous grain and a few flecks and scratches. For something as historic as Mothra, it’s a plus point to have the opportunity to experience as it would’ve appeared in a good cinema during the 1960s. Having said that, the colour saturation is fine, and the 1080p high-definition picture looks great. Even if, by today’s standards, some of the footage is ropey, having passed through cameras several times to create its many groundbreaking optical effects.

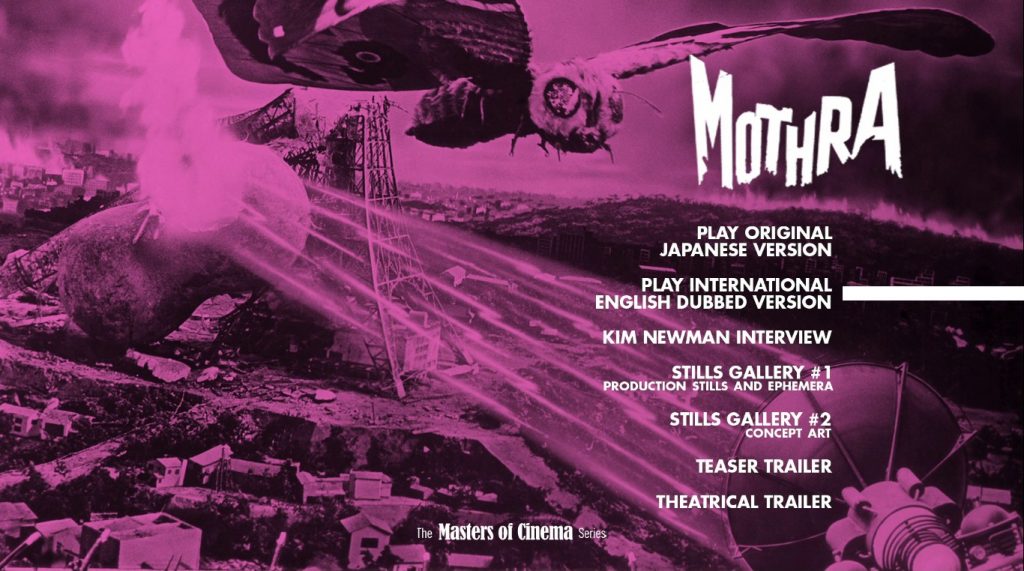

We get the original full-length Japanese version running to 101-minutes, plus the international dubbed version at 90-minutes. There were plans to include the 1974 Champion Festival edit, which compressed the film into a tight 61-minutes, but it sadly didn’t end up in this package—which is a shame, but would only really interest hardcore kaiju aficionados. But I suspect those are who this limited edition of 3000 copies is meant to attract. All three versions would be valid, having been cut by, or according to, director Ishirō Honda’s instructions.

Honda, certainly during the ’60s, was Japan’s most successful director at the box office and pretty much invented the kaiju movie when he wrote and directed Godzilla (1954). He would direct many more, of which Mothra was his seventh and, in many ways, re-defined and revitalised the genre. He’s widely known for his science fiction and fantasy action films, but even during the ’60s and ’70s, when he was churning these out for kaiju specialists Toho Studios, he continued making a few obscure comedies, romantic dramas and arthouse fare.

He started his film career in the early-1930s. While studying at the fledgling film school at Nihon University, he also worked at PCL (Photographic Chemical Laboratories) where he began writing scripts in the editing department, eventually stepping in as assistant director to Sotoji Kimura. His studies and early career were interrupted in 1934, when he was drafted into the military to fight in World War II. He survived a chequered and somewhat chaotic military service in an army fractured by loyalties to an outmoded feudal shogunate system. After the war, he returned to his job at PCL which, in 1937, had been renamed Toho Studios.

Almost all Japanese post-war cinema deals with the fallout from that conflict and addresses the nation’s struggle to contextualise its imperialist history and reconstruct a valid cultural identity that recognised heritage whilst reassessing its values. A serious mission for sure, but after a gruelling six years of frontline service, Honda bore the psychological scars and it seems he preferred to share his dreams with others rather than his nightmares. It’s not all that surprising he gradually veered away from the serious dramas, documentaries, and state propaganda films of his earlier film career and moved into escapist fantasy worlds.

Ishirō Honda is a serious director, having some fun here. He followed the original Godzilla with Rodan (1956), about a radioactively renovated pterosaur. He then tried out a similar idea with The Mysterians (1957) featuring Moguera, a giant alien robot instead of a massive nuclear mutant. His genre success enticed him to embrace the science fiction genre with The H Man (1958) and Battle in Outer Space (1959) following in quick succession. Then came a new kind of ‘monster’: Mothra. Yes, a giant moth! How terrifying is that? Well, that’s not the point…

We start in familiar territory with a ship lost at sea during a typhoon. Just as the last search and rescue helicopter is about to run out of fuel and return to base, they’re surprised to spot some of the survivors on the rocky shore of Infant Island, a barren volcanic atoll thought to be uninhabited, used for nuclear testing with a deadly level of radioactive residue. The survivors are brought back and not only do they lack any signs of radiation sickness, but they also have tales to tell of being looked after by the islanders in the midst of a lush paradise.

The scientific briefing is infiltrated by Senichiro ‘Snapping-Turtle’ Fukuda (Furankî Sakai), a reporter who earned his nickname because when he gets hold of a story he never lets go. So, he and his photo-journalist accomplice, Michi (Kyôko Kagawa), are there at the harbour to cover the send-off for an international scientific mission to investigate the mysterious island. Snapping-Turtle gets ‘lost in the crowd’ and manages to stowaway on the vessel.

Before they reach the island, he’s rumbled by Nelson (Jerry Itô), leader of the Rolisican scientific team, except it soon becomes clear that he’s no scientist and only interested in opportunities to turn a quick profit. Rosilica being a fictional country that seems to share characteristics of both Russia and America, he embodies most of the negative traits of the western, or at least non-Japanese, world.

On reaching Infant Island, we find ourselves in a very ‘Lost World’ scenario that could’ve been dreamt-up by Conan Doyle or Rice Burroughs. The team, clad in full hazmat suits, soon stumble across a hidden valley where the vegetation’s grown to prehistoric proportions. In a patch of forest that’s actually made up of giant mould, resembling something from an alien world of classic Star Trek, they discover a lost civilisation. They also find two fairies (played by twins Emi and Yumi Itô) who communicate in a sort of electronic melody, combined with telepathy.

In true comic-book villain mode, Nelson collects them as specimens, but the more ethical Japanese scientific leader, Dr Chûjô (Hiroshi Koizumi), convinces him to let them go. Little does he suspect that Nelson will later return, in secret, to recapture the ‘tiny beauties’. During this night-time raid, Nelson and his men shoot several of the normal-sized natives who try to defend the diminutive damsels.

This sequence is really pivotal, but also the one a modern audience my find fault in. The islanders are portrayed using ‘blackface’ makeup, which has fallen from fashion lately, to say the least! I’m not sure if they’re supposed to be black, or whether they’re wearing ceremonial muds as a kind of war paint. It’s so badly applied and clearly not their skin colour, so I’m going for the latter. Either way, it’s made clear that, to Nelson at least, these natives are ‘The Other’ and he considers their lives of less value than his potential profits. This is the most important of his many character flaws and his xenophobic fear will lead to his psychological unravelling and ultimate undoing.

It’s actually the ethical and moral interactions of the human characters that drive the narrative here, and this is what marks it apart from earlier kaiju films. Usually, the monster drives the plot by threatening humanity who then have to find a way to thwart it. The threat is usually something that may have been triggered by human misadventure but manifests in non-human form. Like a giant lizard of destruction, for example. That’s a fairly standard template that many kaiju films share with the creature features typical of 1950s America.

Here, things play out differently and that’s why Mothra breathed new life into the genre. Really, Nelson is the monster. The expected fantasy monster doesn’t show up until the half-way mark after the human to human dynamics have been established. Don’t worry, it never gets too serious and there’s still more than enough city-scale monster mayhem to come.

At the time, Furankî Sakai was a huge star in Japan, known for his musical and comedy roles and would’ve been one of the film’s major box office draws. His ‘Snapping-Turtle’ may be a dramatic role but he brings his light touch and keeps the proceedings fun and entertaining, even when there are some serious themes bubbling beneath the surface. He would later become well-known to western audiences as Lord Yabu, starring opposite Richard Chamberlain in the television miniseries Shōgun (1980).

The other main promotional feature for domestic audiences would’ve been the tiny ladies, who were a well known singing due called The Peanuts. They’d had a few chart hits and were looking to reach a bigger international audience. Apparently, the part of the fairies was re-written to accommodate them in the role, reducing the number from four to two. Mothra’s theme song composed by Yūji Koseki, which they sing a few times, is surprisingly catchy and it’s addictive enough to leave the Blu-ray menu up long enough for a few replays. It does sound like it would sit well over the end credits of a Spaghetti Western, though.

What Nelson doesn’t know when he abducts the fairies is that they’re priestesses and the islanders worship a massive egg. After he leaves, the natives perform a rousing song and dance in their ancient temple to awaken their great god. If it’s all starting to sound a bit King Kong (1933), then that’s not surprising. King Kong really set the mould for all giant creature stories to follow and there are several scenes and story elements in Mothra that were intentional homages.

The first treatment of Mothra had been co-authored by Takehiko Fukunaga, Shinichiro Nakamura, and Yoshie Hotta and published as ‘The Luminous Fairies and Mothra’, a serialised novel in ‘Weekly Asahi’ magazine, ahead of the film’s release. This was a marketing ploy borrowed from King Kong, which had also been published as a novelisation a couple of months prior to the film’s premiere. The final script was written by Shin’ichi Sekizawa, who also wrote just about all of Toho’s science fiction and Kaiju films that you can think of, and then some. What made it to the screen bore little resemblance to the book, having been pared-down and imbued with more elegance and strangeness.

Eiji Tsuburaya, the inventive genius behind most of Toho’s SFX films, was a true cinematic pioneer and, in technical terms, a direct descendant of Willis O’Brien. He started out as a researcher and model-maker working in a toy factory where he started to dream about the potential of using miniatures in movie effects. During the mind-1920s, he found work as a camera operator and in 1927 was the first to use camera cranes in Japan and also experimented with super-imposition to create illusions we would now call special optical effects.

For him, King Kong changed everything and he knew it was possible to make a film totally reliant on special effects. He analysed it in great detail to work out how Willis O’Brien had created the spectacle, and soon set up his own special effects company. Everything was interrupted by WWII, but afterward he joined Toho in the early 1950s, where he became a repeat collaborator with Ishirō Honda. Together they created the kaiju franchise that rocketed the studios to spectacular success.

At the time, Mothra was by far their biggest success, partly due to the US distribution deal with Columbia Pictures, clinched on the back of Battle in Outer Space, which had been a big hit for Toho in the US and more-or-less bankrolled Mothra. Also, partly due to its casual weirdness and comfortable, family-friendly approach.

It reminds me of my formative experiences with the Harryhausen films, particularly The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), which even had a ‘tiny beauty’ transported in a cage and played with the magic of cinema to create illusions of scale. There seemed to be a vogue for films where the microcosm becomes tangibly human scale, humans shrink and small things are made gigantic: The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), Them! (1954), The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958), and so on.

Another overt reference to King Kong is that Nelson reveals himself to be an unscrupulous showman who takes the Infant Island Fairies away to Rolisica, where he exploits them for his own capitalist greed, forcing them to perform in his shows. What he doesn’t know is that they’re telepathically linked to their god Mothra and their singing’s a kind of empathy beacon that lets her home in on them over great distances… but, of course, moths don’t come out of the egg fully formed and for a good chunk of the film, Mothra is a great big, havoc-wreaking caterpillar.

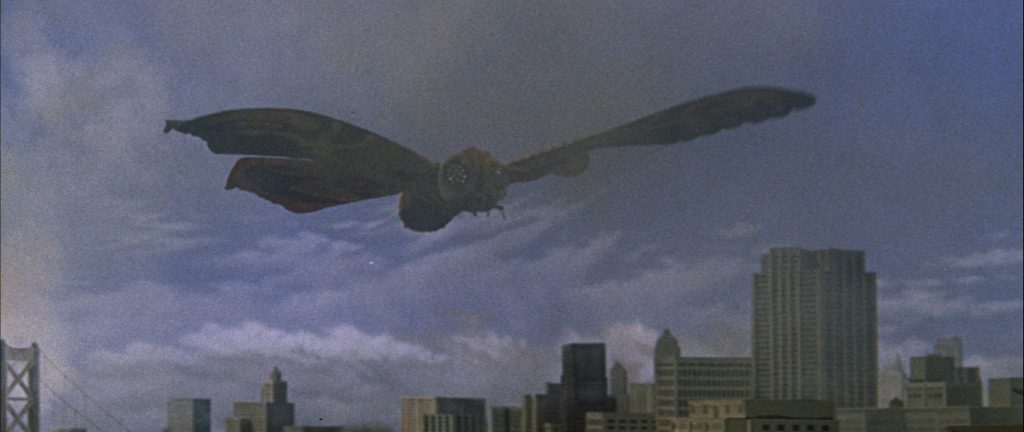

It swims across the ocean, enduring missile attack from miniature jets, to reach mainland Japan and follows Nelson’s path to Tokyo where it busts dams and flattens anything in its path before meeting with the mobilised military. Even their state-of-the-art nuclear heat cannons have little effect and, just as Kong had scaled the Empire State Building, Mothra climbs and brings down the Tokyo Tower, a feature of the city’s skyline which had only been completed in 1958. But, unlike Kong, the climbing of an iconic structure doesn’t signal its demise as it weaves a cocoon and welcomes the energy of the heat rays to hasten its metamorphosis into…

Mothra herself, a beautiful monster! Her legions of fans might even call her cute and cuddly. Based on the wild silk moth, she represents something of Japan’s heritage. Silk had been a major commodity traded with the west, along the historic ‘silk road’. It’s a material literally entwined with their cultural identity. Silk moths had been of great value and a guarded ‘trade secret’ along with links to their food plants.

Moths feature in Japanese mythology in the form of Shinchū, also called ‘holy insects’. These are deities that manifest as gargantuan moth-like beasts, with massive mandibles or fang-lined maws. They’re guardian spirits though and will protect humans by seeking out and devouring the evil spirits that cause disease and misfortune. I’m not going to give too much away about the movie’s climax, but this knowledge suggests an alternative reading.

Mothra may represent mythologies and cultural heritage that have survived in the Japanese psyche. In the post-war period, when Japan was taking a long, hard look at its heritage, these pre-imperialist ideologies come to the fore once more. As kaiju, they appear stronger and visit havoc upon the west not by nuclear retaliation, but by a recognition of cultural values and the inherent human ethics they may embody. By the time Mothra emerges from her cocoon, Nelson’s flown back to Rosilica with the priestesses. The indiscriminate destruction of Rosilica’s New Kirk City, caused by the downdraught from the giant moth’s wingbeats, has unmistakable echoes of a nuclear blast. But it was Columbia Pictures that insisted the destruction be brought to a non-Japanese and recognisably American city!

When it’s all said and done, we have a family-friendly fantasy epic with a feel-good factor unlike many of the other kaiju films I’ve seen. There’s enough cliché to satisfy, but it’s not predictable and certainly would’ve been incredibly original back in the early-’60s. The characters are likeable, except for the villain who’s totally hate-able in his self-serving disregard for all morals and other living things—the kind of guy who knows the price of everything but the value of nothing. Don’t worry, he’ll get his. Good wins out by always doing the right thing regardless of risk and with no immediate reward… and evil defeats itself, with a little help from a massive mythical moth! With Mothra, Toho set out a new model for the monster movie, where the real monsters are us, but so are the heroes… and the monster is a totem, an incorruptible force of nature with whom our sympathies lie.

Hope, salvation and plenty of good-natured destruction along the way! What more do you want?

JAPAN | 1961 | 101 MINUTES • 62 MINUTES (RE-ISSUE) • 90 MINUTES (THEATRICAL) • 91 MINUTES (VHS RE-ISSUE) • 86 MINUTES (TV EDIT) | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE • ENGLISH • INDONESIAN

director: Ishirō Honda.

writer: Shinichi Sekizawa (based on ‘The Luminous Fairies and Mother’ by Shin’ichirō Nakamura, Takehiko Fukunaga & Yoshie Hotta).

starring: Frankie Sakai, Hiroshi Koizumi, Kyōko Kagawa & The Peanuts.