THE MAN WHO WOULD BE KING (1975)

In Victorian India, two ne’er-do-well soldiers scheme to conquer remote lands on their own.

In Victorian India, two ne’er-do-well soldiers scheme to conquer remote lands on their own.

John Huston’s long-in-development adaptation of The Man Who Would Be King isn’t quite what it seems, much like Rudyard Kipling’s 1888 short story. On the surface, it’s a Boy’s Own tale of derring-do that pits plucky, clever British soldiers against primitive benighted heathens, and appears to have much more in common with the likes of The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935) or Gunga Din (1939) than with the cynical cinema of the mid-1970s. Nevertheless, in its own way, Huston’s movie (like the source material) questions the idea of imperialism, albeit from a western perspective.

After an atmospheric opening sequence in an Indian market, complete with snake-charmer and scorpion-eater, where Huston is already demonstrating how deeply his film will revel in exoticism, the story proper opens with Rudyard Kipling (Christopher Plummer) writing a poem in his newspaper office. (Although not identified, it’s The Ballad of Boh Da Thone, penned the same year as The Man Who Would Be King was published—a nice touch). Soon, a shuffling, rag-clad figure enters called Peachy Carnahan (Michael Caine), whose unrecognised by Kipling at first, having been ravaged by dirt or sunburn or frostbite or all three. Indeed, we can only tell it’s Caine from his voice.

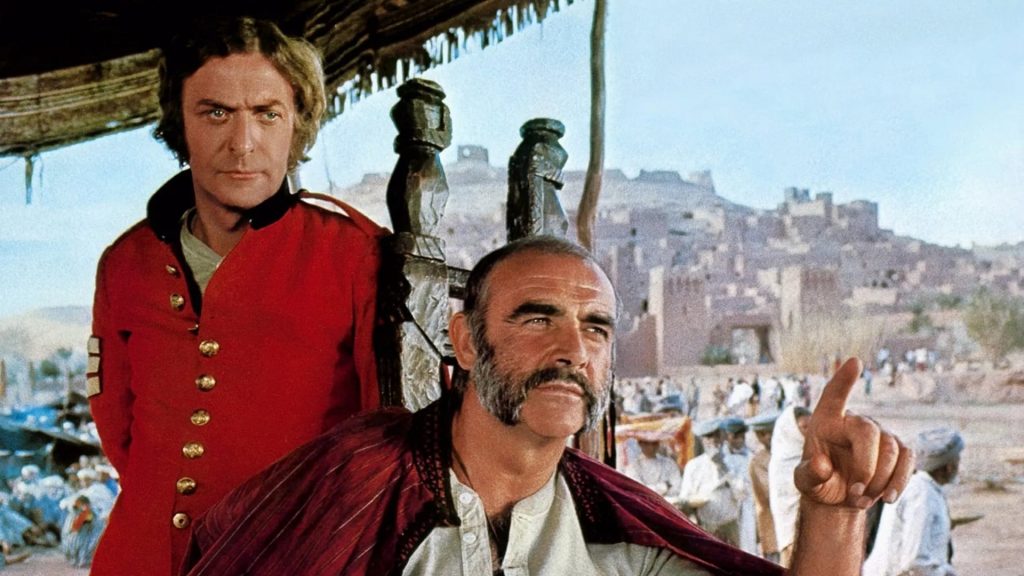

The rest of the narrative is told in flashback, relating Kipling’s first encounter with a much fresher-faced Peachy on a train, a subsequent visit from Peachy (a former British soldier turned semi-criminal freelance adventurer) and his brother-in-arms Daniel Dravot (Sean Connery), and then the main story: the pair’s scheme to traverse the Khyber Pass and establish themselves as kings in Kafiristan, a wild and remote area in modern-day Afghanistan. In this they succeed, for a while, and the bulk of the film covers their ascent to power and then their undoing.

Strictly speaking, everything that happens after they leave for Kafiristan is a story told by Peachy (who has returned barely alive) to Kipling. But in practice we soon forget this, and the adventure is presented in what amounts to a straightforward third-person perspective, albeit one that’s often more mindful of Peachy’s perspective than Daniel’s. It certainly isn’t interested in anyone else’s, as only one of the local characters, Billy Fish (Saeed Jaffrey), is of any significance (although Larbi Doghmi’s amusing as an ineffectual chieftain), and generally they only feature as either impediments or aids to the Britons’ escapade.

This inevitably raises the risk that The Man Who Would Be King will be seen as irredeemably racist, and there are—to today’s eyes—some misjudgements that compound this: notably the watermelon-munching comedy Indian who shares a railway carriage with Peachy and Kipling early on, not to mention some questionable portrayals of Kafiristan culture (the warriors’ face masks look more African than Central Asian).

But even if little details betray the kind of casually racist attitudes that were still endemic in 1975, on a broader level the film’s less arrogant than some might assume. If the Asians are ineluctably ‘other’ (and it’s difficult to imagine how they could be anything else without departing a long way from Kipling), it’s not an Otherness intended to diminish. Quite the opposite, perhaps: the inability of Peachy and Daniel to truly control a culture so alien to them, and their self-deception in believing they can, is a large part of the point. So, while The Man Who Would Be King does romp merrily amid the action-adventure tropes of the British Empire, it emphatically does not take a viewpoint of imperialist superiority.

It’s largely faithful to Kipling, with only one major departure—Billy in the film is a former Gurkha soldier for the British, enabling him to act as a kind of go-between and translator for Danny and Peachy, whereas in the story he’s a local chief himself.

However, its fidelity to the source may be the biggest flaw in The Man Who Would Be King, necessitating some long and rather roundabout episodes at the beginning where Kipling first meets Peachy on a train, then finds Danny on another, then encounters them both together, and so on. As a result we’re almost halfway through the film before the duo’s takeover of Kafiristan actually gets going, and these early scenes add little of importance. Huston and co-writer Gladys Hill could easily have found a simpler and briefer way to explain how Kipling comes to know the two ex-soldiers. But it’ a movie that loves its setting as much as its characters (witness the numerous overhead shots), and the digressions around colonial India undoubtedly provide plenty of colourful setting.

Besides all that, it’s a highly skilful and effective piece of screenwriting, and even if the overall arc is conventional, individual scenes can surprise. Among the highlights is the moment where Peachy and Daniel, coming through the mountains, encounter a pair of giant idols in the snow that mark the entry to Kafiristan; and a scene later on where the attitude of some potentially hostile priests is transformed as soon as they see the pendant that Daniel is wearing. (Here there’s another, more minor, narrative weakness—the assumption that the audience will recognise symbols and terms of Freemasonry. Although, to be fair to the filmmakers, such knowledge was perhaps more commonplace in 1975 than today.)

Many other scenes, meanwhile, have to be admired for the sheer unashamed confidence with which they embrace the colonial-adventure genre, even if the film will eventually sabotage its assumptions. At one point during the Brit’s trip to Kafiristan, for example, a shot fired by Peachy causes an avalanche which strands them; facing death together, they are cheerful, and their laughter soon causes another avalanche which saves them. There’s nothing knowing or ironic about this sequence, which could easily come from a movie of 1935, and one of Huston’s finest achievements in The Man Who Would Be King is that such traditional heroics co-exist so well with a more sceptical attitude; neither seems to undermine the other.

Equally well-handled is the one really important character development in the film: Daniel’s growing belief in his own divine invulnerability after the priests of Kafiristan have hailed him as a god. (The title of The Man Who Would Be King is odd, in fact, because both men want to be kings. It’s Daniel’s obsession with higher status that ultimately scuppers their ambitions.) The key line is the one where he addresses Peachy and Billy as “you mortals”, and it’s not entirely clear if he’s joking or serious, but the groundwork has been laid earlier. From the first battle we see that Daniel is more impetuous than Peachy, and even his weaker skills at doing sums may suggest that he can’t see hard facts as clearly. Music, too, helps underline the point, with the ceremonial gongs, drums and horns of Kafiristan seeming ominous even while they are ostensibly celebrating his triumph.

While Caine (especially) and Connery acquit themselves well, they could hardly do otherwise: the casting is so spot-on that they barely have to act, just take care not to over-act, and their likeability is vital to the film. (A more cynical movie could, of cours,e be made with Peachy and Daniel as bad guys—but this isn’t it.) Few of the others considered over the decades for the parts—Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart, Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Robert Redford, Paul Newman (there’s something quite Butch Cassidy about the Peachy-Daniel relationship)—could possibly have worked so well, although it’s believable that two further choices, Richard Burton and Peter O’Toole, might have. Jaffrey also gives depth to what could be a stereotyped role, while Jack May is terrific in a smaller part as a supercilious functionary of the Raj.

It’s essentially a film of story rather than character, though, and if it can seem a little superficial and rushed after a rather slow start, it has some undeniably gripping sequences. Above all, the sweep of it is intoxicating: the landscapes (mostly Morocco), the hidden city that looks like something out of Game of Thrones crossed with Lost Horizon, the profuse Victorian detail.

Film critic Pauline Kael was right to point out that Huston maintains a distance from his characters, and as a result it’s not an emotionally engaging movie taken as a whole, but still there are many scenes that can’t fail to stir. Roger Ebert called it “swashbuckling adventure, pure and simple, from the hand of a master”, while Vincent Canby in The New York Times observed that The Man Who Would Be King “has just enough romantic nonsense in it to enchant the child in each of us”. Maurice Jarre’s score helps to amplify this, often best when it is gentle but also notable for a jaunty battle theme that expresses absolutely no sorrow for the bodies littering the screen. (Orchestrating Connery’s final rendition of The Minstrel Boy, though, was surely a mistake; wouldn’t it have been more powerful if he sang it unacommpanied?)

In many ways The Man Who Would Be King already belonged to a past age in 1975. Thematically it has much in common with Huston’s earlier Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), and a late shot of Peachy and Daniel’s plundered loot tumbling down a hillside echoes that film. And certainly it resembles more a movie of the 1930s-50s than one of the weighty, contemplative, self-regarding epics like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) or Doctor Zhivago (1965) that had since become fashionable.

Perhaps as a result, it didn’t do terribly well at the box office, but then it is a very British film in many ways and this was the year of Jaws. Still, Huston’s team managed to gain Academy Award nominations for ‘Best Writing’, ‘Art Direction’, ‘Costume Design’ and ‘Editing’, and even though none of them won, those categories summarise the areas where The Man Who Would Be King excels.

This is, mostly, just what it seems to be: a rousingly told adventure. But even if it’s not profound, it is intelligent, and this may explain why it has endured better than many of its kind.

USA • UK | 1975 | 129 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: John Huston.

writers: John Huston & Gladys Hill (based on the short story by Rudyard Kipling).

starring: Sean Connery, Michael Caine, Christopher Plummer, Saeed Jaffrey & Shakira Caine.