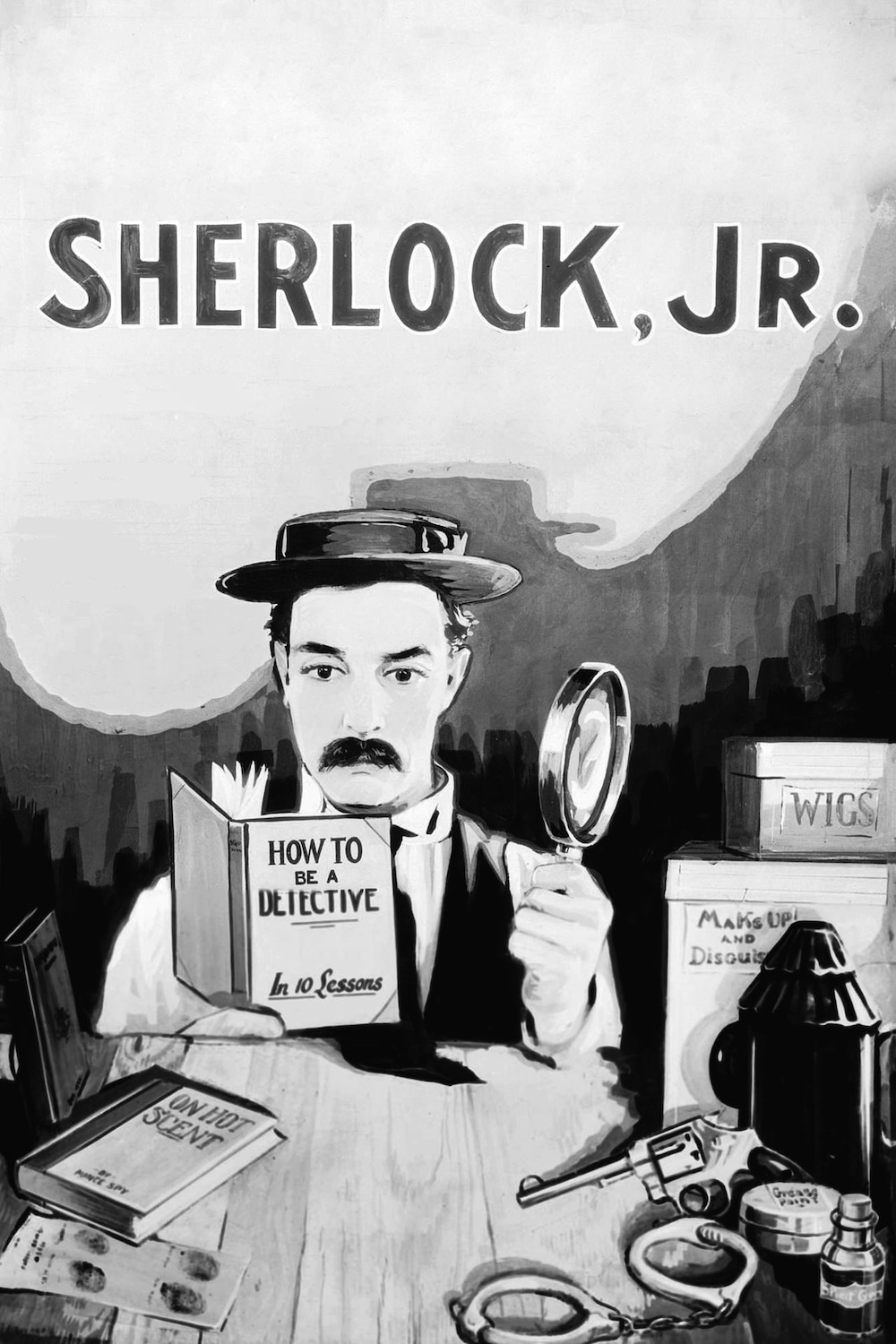

SHERLOCK JR. (1924)

A film projectionist longs to be a detective, and puts his meagre skills to work when he's framed by a rival for stealing his girlfriend's father's pocket watch.

A film projectionist longs to be a detective, and puts his meagre skills to work when he's framed by a rival for stealing his girlfriend's father's pocket watch.

There are a number of brilliant comedians from Hollywood’s silent era. The most famous is undoubtedly Charlie Chaplin, whose signature character, the Tramp, made him instantly recognisable around the world. Laurel and Hardy also became the most successful comedy duo ever, while also making a superb transition from silent films to talkies. However, in my opinion, the best of them all was the great Buster Keaton.

It appears Keaton was destined to become a master of cinema. Having begun his career as a child performer, acting alongside his mother and father in their vaudeville show, he transitioned into filmmaking. Cinema was all the richer for it. This couldn’t have been more evident than in his first great film: Sherlock Jr. Released a century ago this month, the five-reel picture may only be 45 minutes long, but it showcases all the technical mastery and cinematic brilliance that would turn the Great Stone Face into an icon.

The film opens with a proverb: “Don’t try to do two things at once and expect to do justice to both.” Ironically, Keaton does exactly that, if not more. Working as director, producer, editor, and star, Keaton demonstrates that he could, in fact, do many things at once. When watching any of the comedian’s films, it always feels like a one-man show.

This title card also sets the scene, improbable though it is: “This is the story of a boy who tried it. While employed as a moving picture operator in a small town theatre, he was also studying to be a detective.” As we find out throughout the duration of the film, the plot barely matters; it merely serves as a device for Keaton to experiment with the medium. 100 years later, his tinkering with cinema is still inordinately impressive.

Firstly, if you’ve ever wanted a lesson in storytelling, then you need look no further than the work of Buster Keaton. His films demonstrate a complete narrative economy, perhaps because the story itself was of little interest to him. A theme of tragic misunderstandings runs throughout Keaton’s films. In The General (1926), he’s mistaken for a coward when someone misinterprets his discharge from military service. Here, he’s falsely accused of being a petty thief and then ejected from the house of his love interest.

These misunderstandings are brilliant narrative tools: they help to set the plot in motion. We know our character is righteous, even if no one else does. In this way, they provide both a character we can empathise with and a plotline that leans towards redemption. Throw in a love story and there’s nothing left wanting—the audience has someone to root for and an ending they can celebrate. His stories have all the essentials, with any excess trimmed away.

It’s impressive that the stories in Keaton’s films still manage to be well-structured, even though they were practically written as they were being filmed. In Peter Bogdanovich’s documentary The Great Buster: A Celebration (2018), close friends reveal that Keaton often didn’t have a working script for his films. Instead, he and his cohorts would come up with stunts from one day to the next, and then work them into the story.

Whilst his slapstick might be overshadowed by the physical comedy of Laurel and Hardy, his stunts are undeniably second to none. When I’ve shown some of Keaton’s best bits to friends, I’ve noticed they often elicit the response: “How did they do that?!” The truth is, no one truly knows how Keaton managed to achieve everything he could. However, it can be attributed to a talent for acrobatics, a high pain threshold, remarkable ingenuity, and immense bravery.

When you take all that and combine it with a yearning to experiment visually and entertain in ever more original ways, you get a glimpse into Keaton’s style. His dedication to his craft is impressive, though perhaps the most memorable aspect of his films is the audacity of his stunts. While watching a Buster Keaton film, you sometimes can’t help but wince: knowing that all these stunts were genuinely performed, it can make one nervous even a hundred years later. After all, Keaton famously broke his neck performing a stunt in this film, although he wouldn’t realise it for about nine years!

Even then, the less physically demanding stunts still astonish; the pool game is a prime example of this. It’s a bit like Alfred Hitchcock’s bomb under the table, but reversed: an explosive has been hidden in the number 13 ball. We know which number it is, but Keaton doesn’t. Somehow, as he plays his game of pool, he manages to avoid hitting it, sinking every single ball around it until it’s the only one left on the table.

Though you might think it’s all movie trickery (like magnets or clever editing), the game you see on screen was genuinely performed by Buster. He practised with a pool expert for four months, and while several games were played and edited together, all the trick shots are real. Such was his dedication to his craft, his desire to create genuine magic on the screen.

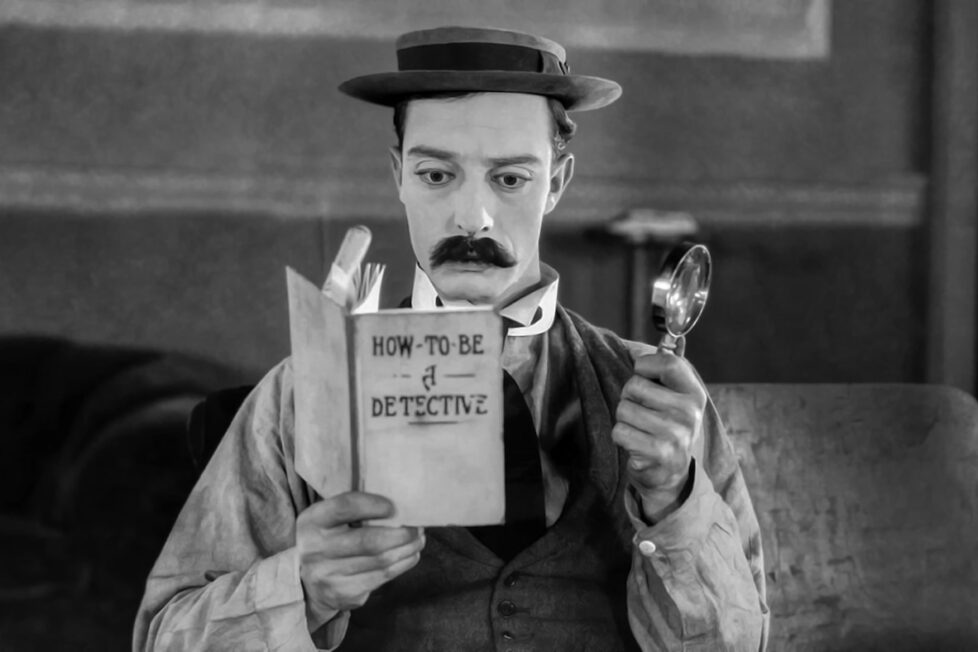

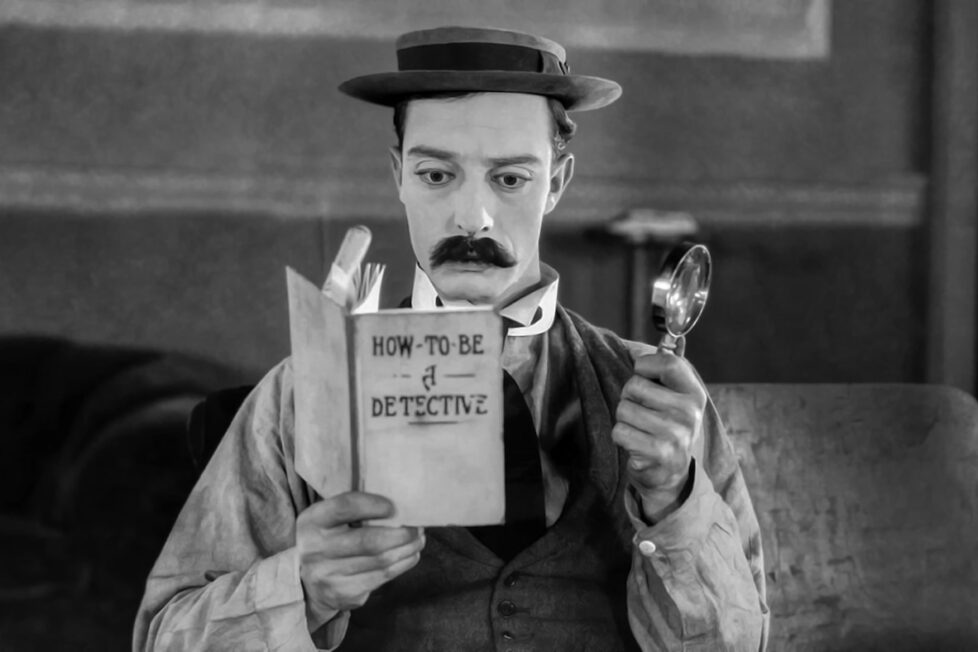

This isn’t to mention the sight gags employed by the former vaudeville star. The film isn’t quite as funny as some of his best work—which, surprisingly, earned it the ire of critics at the time. It still has a lot of humorous moments, though. These include our protagonist studying from a booklet labelled “How To Be A Detective”, sifting through rubbish to find a dollar, or pulling out a magnifying glass to impress his fiancée with her engagement ring.

However, the humour is not what makes the film memorable; instead, it’s the sense of wonder that Keaton generates from his audience, the palpable sensation of an artist’s love for their craft which seeps through the screen. Sherlock Jr. isn’t infinitely re-watchable 100 years after its first release because it’s funny, but because it’s a historical document: it shows one of cinema’s greatest auteurs exploring the possibilities of their art form.

Admittedly, he wasn’t the first. Georges Méliès was arguably the first cinematic magician to leave audiences scratching their heads in wonder. However, Keaton was undeniably the first to make cinematic sorcery so funny. Perhaps this is why critics of the time were disappointed by the lack of laughs, but it still doesn’t explain their absence of complete amazement at the trickery on display. If modern audiences are still left dumbfounded by Keaton’s talent, I find it hard to believe there was ever a time when his films didn’t astonish.

Indeed, many of the film’s stunts have you rewinding, trying to work out how on earth they could have possibly done them. This includes Keaton disappearing into a suitcase held by his friend, which looks so believable that I’m left perplexed every time I watch it; wisely, Keaton wouldn’t reveal the secret behind the stunt until a few years before his death. As well as this, he also manages to jump through a window and change costume mid-air, demanding further rewinds.

Of course, the single shot that everyone remembers most vividly is the mesmerising dream sequence where our protagonist attempts to walk into a film. Keaton revealed that the entire reason the picture was made was to capture this shot: the film within a film. It remains so sublimely creative that you can’t help but smile, and that, perhaps, is why the film still works so well. You’re not left guffawing, but rather feeling enamoured: you’re struck by the creator’s desire to break the mould, revolutionise the medium, and pioneer new, previously unimaginable ways of visual communication.

I think it’s for this reason that Buster Keaton remains my favourite silent film comedian. You can point to shots, sequences, or even entire films and see just how much they’ve impacted the whole art form. Arguably, some of my personal favourites from contemporary cinema wouldn’t exist without Keaton’s contributions. Chinese filmmaker Bi Gan’s stunning A Short Story (2022) has clearly taken much visual inspiration from films like Sherlock Jr. Keaton’s influence on cinema is simply impossible to overstate.

Any film buff should watch Sherlock Jr. Luckily, being 100 years old, it’s now in the public domain and can be found on YouTube. This hugely inventive, strikingly original film is brimming with cinematic innovation, truly capturing the essence of cinema. But then again, what The Great Stone Face did for the medium can barely be called filmmaking—it was as close to sorcery as you’re ever likely to find in this art form. Magic, thy name is Buster.

USA | 1924 | 45 MINUTES | 1.33:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH (SILENT)

director: Buster Keaton.

writers: Clyde Bruckman, Jean Havez & Joseph A. Mitchell.

starring: Buster Keaton, Kathryn McGuire, Joe Keaton, Ward Crane & Ford West.