BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID (1969)

Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid are the leaders of a band of outlaws in the early-1900s who go on the run after a train robbery goes wrong...

Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid are the leaders of a band of outlaws in the early-1900s who go on the run after a train robbery goes wrong...

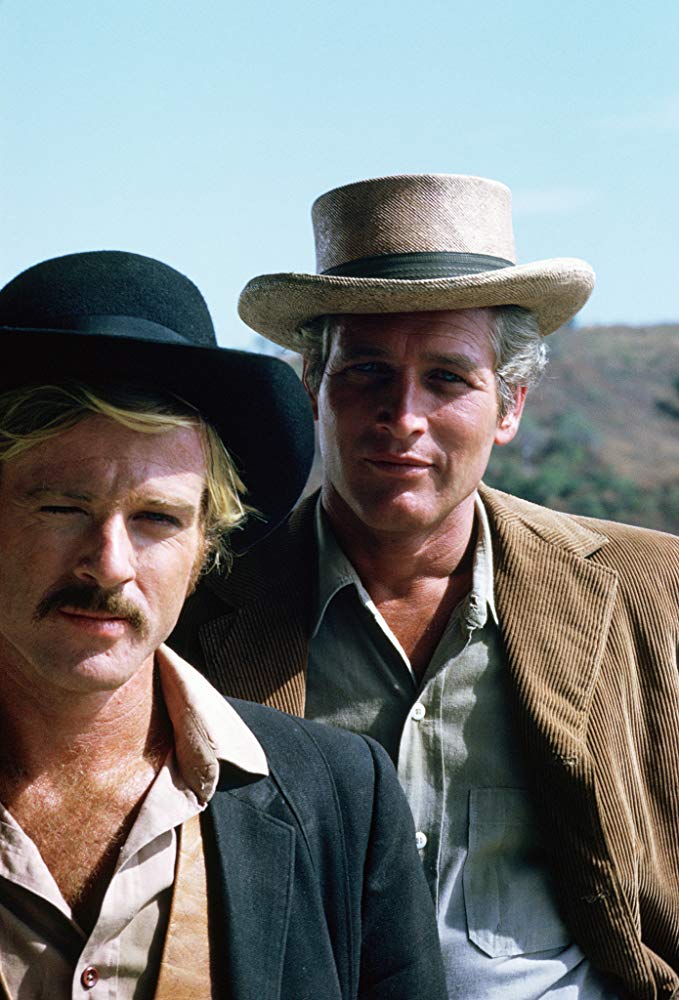

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is a peculiar film. It was a successful mainstream release in 1969, superficially appearing to be one of the most traditional of movie genres (a Western), and yet its megastar lead characters—Butch (Paul Newman) and Sundance (Robert Redford)—are a pair of bickering, rarely competent fussbudgets. They’re about as far from the square-jawed manly heroes of classic Westerns as one can find.

The film also has little in the way of plot. It’s really just a sequence of events connected to a single challenge and its resolution. It’s also completely devoid of any late-1960s angst or counterculture moodiness, so it survives on its leading men’s personalities and its good humour. Although it’s rarely hilarious and certainly isn’t an outright parody like Mel Brooks’ later Blazing Saddles (1979).

The romantic element of the story is (depending on how one wants to interpret it), either a weirdly sexless relationship between Sundance and Etta (Katharine Ross), or a daring ménage à trois involving Butch. The film has hardly any music, and yet it gave us one of the most famous of all movie songs: Burt Bacharach’s classic “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head.”

And underneath its light-heartedness, there’s a tender sadness. Set much later than most Westerns (the story ends in 1908), Butch Cassidy is preoccupied with the passing of years. It reflects not just the transition from the Old West to the 20th-century (“your times is over”, a character tells Butch and Sundance), but also the loss of the mythical “good ol’ days” and their eventual replacement with the ugly, violent 1969 of the Vietnam War, Chappaquiddick, and Charles Manson.

This is foreshadowed in the opening titles, when pseudo-silent, sepia-toned footage, reminiscent of The Great Train Robbery (1903), flickers across a portion of the otherwise dark screen, accompanied by the sound of a clattering projector. “Once they ruled the West!” says a title card, and director George Roy Hill seems to be striving for an effect of double nostalgia.

Hill put audiences simultaneously in the position of 1910 audiences (remembering the recently-departed Butch and Sundance and the Wild West they represented), and in the shoes of people living in 1969, looking back with fondness at the innocence of 1910. For us in 2019, of course, 50 years after Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid premiered, there’s a third level of evocative retrospection as we ponder ’69 as a more innocent time in Hollywood.

Even after this film-within-a-film, we stay with the sepia for the first section of the movie proper. Here, though, we’re quickly introduced to the two things even more important than any abstract themes in Butch Cassidy: Newman and Redford themselves.

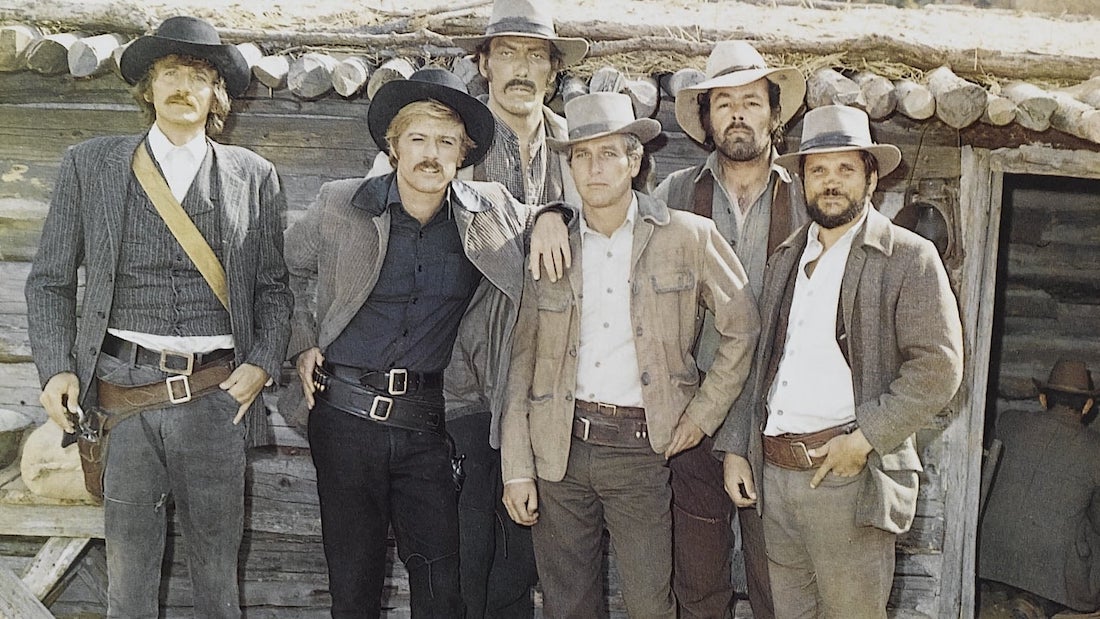

“What the picture works off entirely is the relationship between the two guys,” said an unnamed individual (probably screenwriter William Goldman) in the documentary The Making of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. And even if “entirely” is a bit of an exaggeration, he’s essentially right. Nothing of consequence happens in the film without them. They are hardly separated and the third-and fourth-billed performers (Etta and the mine owner Percy Garris, constantly spitting tobacco juice in an amusing performance by Strother Martin), are a very distant third and fourth indeed.

The writer and director evidently adored their lead characters and, from this first main scene, the film makes no secret of this. We start with a long close-up on Butch as we follow him, checking out a bank as a candidate for robbery, with most of his surroundings dark or blurred, but Newman’s face remains crystal-clear.

We then move to a bar, where the first face we see is Redford’s as Sundance. The camera stays on him for a long time. The tense card game that follows, where nearly any other director would’ve shown at least the whole table, is mostly shot at Sundance’s head-height (though not from his point of view), and it’s not until near the conclusion of it that we even see his opponent’s face or the context of the room.

More than seven-minutes pass from the beginning of the film before we see Butch and Sundance in the same frame together, but once we do, it signals the end of the prelude and the start of the main narrative—where the sepia is replaced by bleached full colour. Butch Cassidy was deliberately over-exposed by esteemed cinematographer Conrad “Connie” Hall (Cool Hand Luke, Marathon Man, American Beauty), lending it a sense of age as well evoking the physical dryness and brightness of the landscapes where the action takes place.

From now on, for the rest of the movie, Butch and Sundance will be together on the screen an extraordinary amount. Sometimes this can seem contrived—for example when Sundance is outside a house talking to Etta, and Butch is leaning through a window so he, too, can remain in-frame. At other points, the pairing feels much less forced—for instance, when Butch and Sundance are being chased (in rather leisurely fashion) away from the scene of a train robbery. The director is apparently content to let us watch them riding. No meaningful conversation, no music, no sound except their horses’ hooves… just “the two guys.”

Despite their dominance of the movie, however, one of the strangest things about it is their relationship with Etta. Far less is known about her than about Butch and Sundance, so while the movie’s in broad terms accurate about their final years, Hill and Goldman seem more willing to go out on a limb with their one important female.

They don’t invest much in her characterisation, perhaps remembering that (as Goldman bluntly put it) “girls are a problem in Westerns because they slow up the action”, and she’s frankly rather bland despite Ross’s best efforts. She also, of course, has to fulfil the awkward task of women in buddy movies generally—not really there to add anything much to the story but confirm the heroes’ heterosexuality.

As a result, Etta exists primarily in terms of her relationship to Butch and Sundance. But exactly what form that takes is ambiguous. For example, nominally she’s Sundance’s girlfriend, but it’s Butch who takes her on the famous bike ride accompanied by “Raindrops”. Immediately before, even while she’s in bed with Sundance, Butch rides around the house on the newfangled machine jokingly chanting “you are mine, Etta Place, mine.” Once they’re on the bike, she offers him an apple, like Eve with Adam. Later, when she speculates that in a different life they might’ve been together, he says:

We are involved. You are riding on my bicycle. In some Arabian countries, that’s the same as being married.

This unmissable implication that the Sundance-Etta relationship is not as simple as it looks continues throughout the film. For example, in a key scene that marks the beginning of the final act when the trio arrives at a railway station in Bolivia, they’re framed so that Butch and Etta are very clearly a couple, while Sundance is the odd one out. It may be no accident that the Butch-Sundance relationship rapidly deteriorates from this point but, in any case, it’s another oddity in a film that on the surface seems so uncomplicated and so feel-good, conceals so many contradictions.

The biggest and most blatant of these contradictions, perhaps, is that neither Butch nor Sundance is a conventional Western hero, for all they look the part. To a large extent, this is down to the writing. As Hill said:

… the characters are modern rather than traditional in approach and temperament, and [the dialogue] has a very contemporary rhythm and sound to it.

But it’s certainly not naturalistic dialogue. In fact, the constant repartee can seem excessively artificial (to the point it occasionally undermines the well-paced thrills of the final shoot-out), and often forces both Newman and Redford to work overtime conveying subtler, more realistic character traits through facial expressions and body language.

And the duo are emphatically not antiheroes in the style of the revisionist “new Westerns” either, of the kind early established by John Wayne in The Searchers (1956) and brought to a laconic apogee by Clint Eastwood in Sergio Leone’s movies of the mid-1960s. Instead, Goldman is keen to undermine the traditional association of the Western with extreme masculinity and emotional reserve.

Both the lead characters are portrayed as men of sensitivity and even, at times, touches of femininity, especially in Newman’s performance (Hill claims at least some historical basis for this, with Butch being “a warm, open, amiable guy” compared to the sulkier Sundance). For example, Butch refers to the “beauty” of an old bank and proves adept at imitating the voice of a pugnacious grandmother on a train they’re robbing.

Then there are non-heroic revelations at key moments: Butch never shoots anyone, Sundance can’t swim. We learn their real, less romantic names, too—Parker and Longabaugh. They aren’t even competent robbers and have trouble living up to their legends.

This smashing of Western genre expectations extends, indeed, to the entire movie. In one of the funniest sequences, a meeting of townsfolk are determinedly uninterested in the sheriff’s attempt to raise a posse, obviously preferring to stay safely in town—but their interest is finally piqued by the prospect of a little consumerism when a bicycle salesman takes the stage.

Even the body count is low, unusually so for a film with such a lot of shooting. In fact, until Butch and Sundance reach Bolivia toward the end (where the irony is that they have to start being murderous just as they’re trying to go straight), hardly anyone dies.

Butch Cassidy certainly has affinities with some more straightforward Westerns of the period. It shares with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), for example, a pleasure in pointing out how far the myths of the West can stray from the actual facts (“Most of what follows is true”, says an early intertitle in Butch Cassidy; “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”, reflects a character in Liberty Valance). It influenced Westerns that came after it, too. An obvious case is Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1974), with its similar use of near-sepia colour schemes and its theme of changing times.

But it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that Butch Cassidy is not just a slightly subversive Western. In truth, it’s not a Western at all, but an affectionate study of a middle-aged friendship that happens to be set toward the tail-end of the Old West.

The passage of time is a dominant theme, but it’s really the men’s age—both were in their early-forties when they finally succumbed to Bolivian government bullets—rather than the fading of the Old West that Butch Cassidy is primarily concerned with. Indeed, a scene Goldman wrote that didn’t make it into the final cut shows them in Bolivia watching a fictionalised film of their own deaths; footage from this became the faux-silent movie at the beginning.

And plenty of references remain in the released version to make it clear they’re on the way out. Butch says that when he was a kid he thought he would grow up to be a hero; it’s too late now, retorts Sundance. A sheriff tells them they should’ve died years ago when they had the chance (to become legends?). Etta tells the pair she’ll do almost anything for them, but “I won’t watch you die. I’ll miss that scene.” And indeed she leaves them, her face speaking volumes of despair when she realises their inability to give up their criminal careers has doomed them.

That bittersweet touch brings us again to the music, which adds to this curious sense that we are watching a story which has wandered from a more obvious locale—say, America in the 1950s, where two men in early middle age struggle to cope with the transformations around them—and found itself, bemused, in a Western setting.

For the music in Butch Cassidy is not only very sparse but also entirely devoid of typically Western motifs, a deliberate decision by Hill (who studied music at Yale before a directorial career that had already included such successes as Hawaii and Thoroughly Modern Millie). The simple melodic title theme consists of only a few notes interspersed with silence and could belong to almost any emotionally-laden film of the period. There’s certainly not a big rousing tune or a plaintive twanging banjo to be heard.

Music appears only a handful of times and there’s no non-diegetic music at all except for the two songs—the celebrated “Raindrops”, which meets Goldman’s specification in the screenplay of being “poignant and pretty as hell”, and then later on Bacharach’s extended, wordless “South American Getaway.”

The latter is less successful. At least “Raindrops” accompanies some substantial character interaction, between Butch and Etta, but “Getaway” gives the impression that the film has simply given up on normal storytelling. It’s certainly memorable, but perhaps for the wrong reasons. (Conversely, a mid-film episode where the trio’s sojourn on the East Coast is told through sepia stills and without dialogue—but with a little music—is much more effective because it has a clear narrative direction.)

The decidedly non-Western character of these songs was not just an aesthetic decision, though. It was a time when filmmakers frequently inserted similar numbers into their movies in hopes of an Academy Award for ‘Best Song’ and, indeed, Raindrops delivered (as did the previous year’s shoehorned-in contender from The Thomas Crown Affair, Michel Legrand’s “The Windmills of Your Mind”.)

Butch Cassidy also won for Hall’s cinematography, Goldman’s screenplay, and (surprisingly) Bacharach’s score as a whole. Hill’s decision to keep the music short and sweet paid off in that respect, although he failed to gain the best director or best picture statuettes despite being nominated for both.

At the box office, meanwhile, it was the top-grossing US movie of 1969, easily beating the more zeitgeist-y likes of Midnight Cowboy and Easy Rider, and confirming that audiences in times of upheaval are not averse to mostly unchallenging good humour.

It reinforced Newman’s status as a superstar (the Will Smith of his generation), as another shining moment in a career that had already included films like Exodus (1960), The Hustler (1961), Hud (1963), and Cool Hand Luke (1967). It set Redford on a similar trajectory, something he recognised when he named his Sundance Film Festival. These two actors and Hill would repeat the magic with the somewhat similar movie The Sting (1973). Even today, Newman and Redford remain so identified with Butch Cassidy that it’s not easy to imagine Steve McQueen, Marlon Brando, or even Warren Beatty (three actors considered for Sundance) in the film.

For Goldman, this was just another hit in a string of successes (All the President’s Men, Marathon Man, The Princess Bride, Misery, A Bridge Too Far), making him one of the most famous screenwriters in Hollywood.

Perhaps more importantly than any of these individual successes, though, Butch Cassidy stands apart as one of the finest buddy movies ever made. A film that’s truly interested in contemplating friendship rather than using it as a launchpad for adventure. The characters are emphatically equal in a way we rarely see (never a principal hero and a lesser sidekick) and there are moments of terrific tenderness—like Sundance wrapping Butch’s injured hand in the final minutes of the movie.

If it’s sometimes a little too cute or feels a little unsatisfying, it’s unfailingly likeable from beginning to end, and can also be genuinely moving. And it’s in those last minutes—when its gentle escapism has drifted almost imperceptibly into desperation—that Hill brings out his masterstroke: cutting the action an instant before the bullets strike Butch and Sundance. Ending the film on a sepia freeze-frame.

It’s the exact opposite of what Arthur Penn had done at the end of Bonnie and Clyde (1967), by deliberately showing the titular couple being ingloriously mowed down. Hill, instead, in consigning his flawed and non-heroic characters into legend while they’re still alive, elevates their story and his movie to strange greatness.

director: George Roy Hill.

writer: William Goldman.

starring: Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Katharine Ross, Strother Martin, Jeff Corey & Henry Jones.