LIBIDO (1965)

A young man visits his ancestral home accompanied by his guardian and their wives, where he is plagued by the memories and influence of his murderous, psychosexual father.

A young man visits his ancestral home accompanied by his guardian and their wives, where he is plagued by the memories and influence of his murderous, psychosexual father.

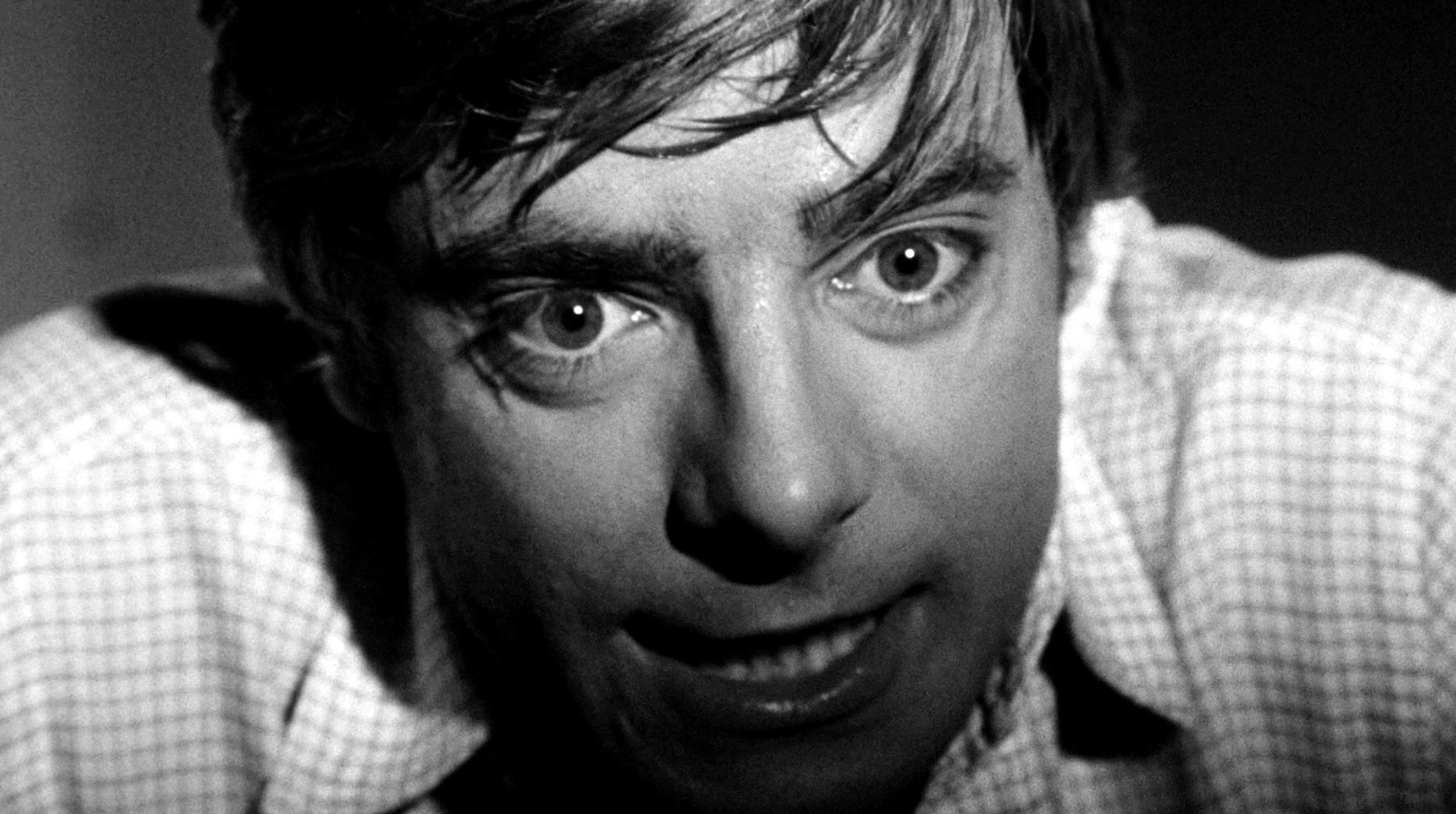

Over the years, Libido has earned unwarranted notoriety as a shocking “sleazefest”. This misconception arose from its initial release, which caused a stir for pushing the boundaries of acceptability with an opening gambit of sexualised violence—effectively suggested without being explicitly shown—alongside a satisfyingly dark dénouement. Now, with this 2K restoration from Radiance on Blu-ray, lovers of Italian pulp cinema can satisfy their curiosity and appreciate its neo-Gothic psychological suspense in all its pristine monochrome glory. It may have some murky themes, but the puzzle at the heart of its plot is a pleasure to solve.

The film opens with text explaining Sigmund Freud’s notion of the libido: a fundamental urge strongly linked with sexual desire. The father of psychoanalysis also believed it could be perverted by childhood trauma during the imprinting of sexuality. This idea was seized upon by countless thriller writers and filmmakers as an explanation for their psychopathic antagonists. Two notable precursors, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Marnie (1964), rest entirely on this concept, as do many of the key gialli that followed.

Critics seem divided on whether to call Libido a giallo, a debate arising from the ill-defined term itself. In Italy, giallo is simply a label for all mystery pulp thrillers, applying equally to Edgar Allan Poe, Agatha Christie, and Dario Argento. Only in English-language genre theory does “The Italian Giallo” have the particular connotations that writer-director Ernesto Gastaldi helped establish. Indeed, he was fresh from uncredited script duties on The Possessed (1965)—another equally important and underseen proto-giallo—and would go on to write another 10 definitive examples over the next six years.

What we now accept as a giallo is usually a convoluted and cleverly contrived whodunnit with plenty of red herrings, misdirection, and stylishly shocking set-pieces. There’s often a mysterious black-gloved serial killer who, invariably, is labelled a “maniac” with an amateur sleuth on their trail. Libido ticks enough of those boxes that genre aficionados might feel they’ve seen it all before. But, actually, they’ve seen a lot of it since. Though not quite a fully fledged giallo, it’s a noteworthy template and one of the films that laid the foundation for the genre’s meteoric rise in popularity, which dominated Italy’s box office until the mid-1970s.

The pre-title sequence alone features a young boy playing with a creepy Jiminy Cricket music box as he witnesses the protracted murder of a bondaged blonde at the hands of his father. It’s strong stuff for the mid-1960s, though it follows the path signposted by the groundbreaking psycho-thriller Peeping Tom (1960).

From those opening scenes, we see clear signalling of innocence lost and trust shattered at a time when a young mind is already struggling to make sense of the adult world. The tinkly tune of a music box, suddenly sinister by association, is used as an auditory cue for impending trauma or a reawakening of a Freudian fugue state. It’s since become a horror staple, though there were few precedents at the time. For example, music boxes or ballerina jewellery cases cropped up in several 1950s films, but usually as emotional punctuation to evoke nostalgia or to link a character’s transition from child to adult. Only a few earlier movies employ it as a sinister signifier with narrative import as Gastaldi does here.

Mervyn LeRoy famously used a child’s music box in his dark psychological thriller The Bad Seed (1956) as a key component of a curated portrait of innocence, escalating suspense and counterpointing the suspicion that the child may be malevolent. There are other thematic overlaps with Libido, though Gastaldi stokes our suspicions not of a child, but about the “inner child” of an adult—perhaps a man whose emotional development was arrested in childhood, rendering him incapable of functioning in a fearful adult world.

I recall a music box in William Castle’s House on Haunted Hill (1959) being used as auditory shorthand for the past resurfacing, confirming it as a classic haunted house trope. In Libido, the clockwork cricket that doffs its top hat to a recurring tune goes beyond a simple dramatic contrivance to become an integral plot point. Similar pretty little tunes quickly became part of the Italian horror and giallo soundscape.

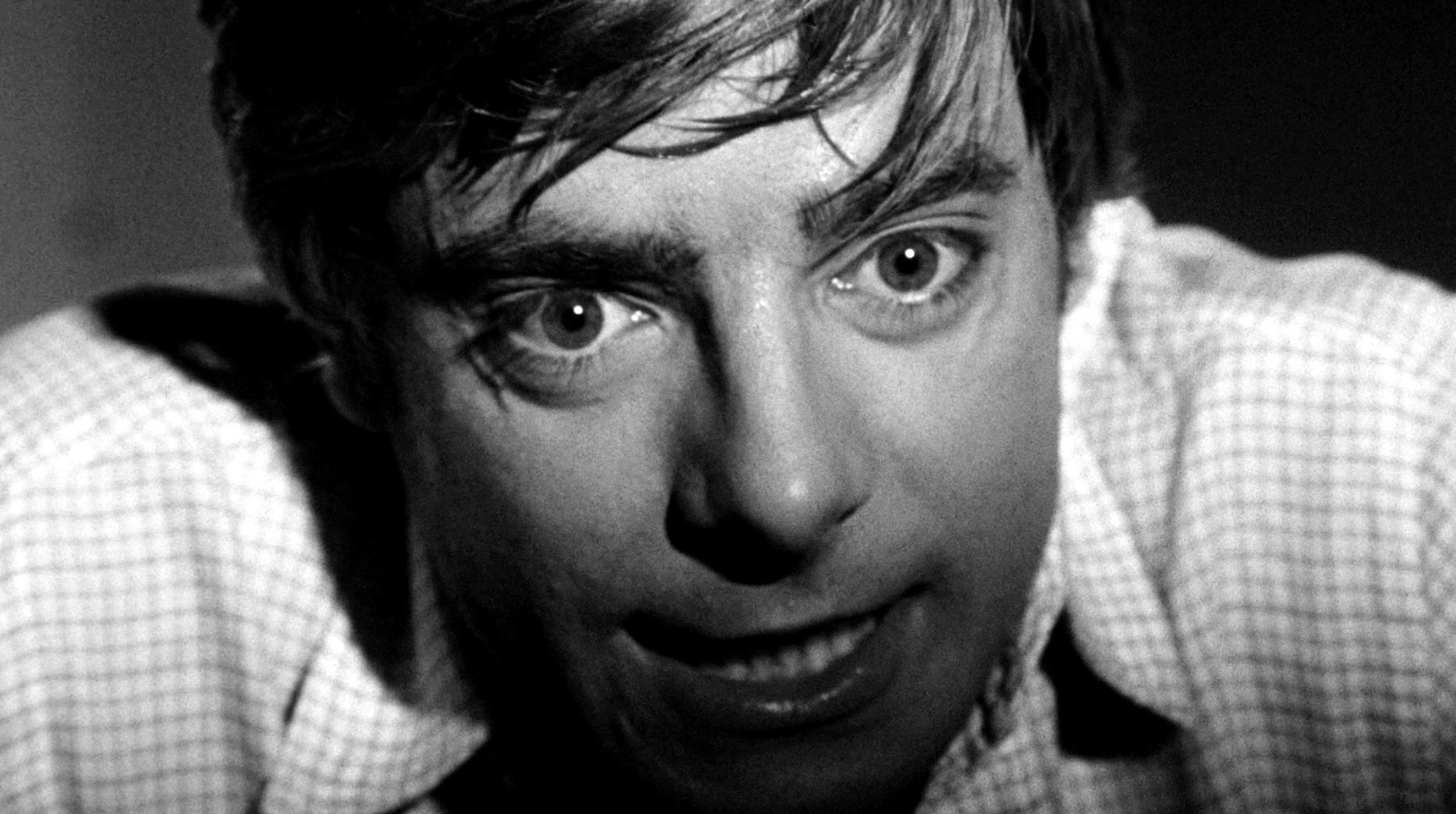

From the dead eyes of the battered woman, reflected to infinity by the mirrored walls of the bedroom, the camera closes in on the eyes of the young witness and transitions to the adult Christian Coreau (Giancarlo Giannini). There’s no dialogue yet, but the story is already underway; Gastaldi keeps his cinematic linguistics just as clear and concise throughout.

It’s been 20 years since the night Christian’s father murdered the woman before throwing himself off nearby cliffs. Christian is returning for the first time to the family villa he now stands to inherit. He arrives with his new wife, Helene (Dominique Boschero); Paul (Blood and Black Lace’s Luciano Pigozzi), the trustee of the family fortune and caretaker of the estate; and Brigitte (Mara Maryl), Paul’s young wife, who looks exactly like the woman murdered in the house all those years ago. They are there to conduct an inventory and estimate the costs of repairs and refurbishment.

It reads like a classic Agatha Christie set-up, with a group of people brought together in an isolated location. We immediately anticipate the death of one of the quartet. However, this is where we veer away from the expected gialloformat. Instead of a series of murders that narrow down the suspects, we are presented with hints of a haunting. Christian seems surprisingly resilient until he begins to see and hear strange things in the night. Lured by the familiar melody of his childhood toy, he discovers a rocking chair in motion in an empty room. His father’s distinctive pipe, its bowl carved as a skull, rests nearby, still smouldering. On another occasion, he hears footsteps and glimpses a figure dressed as he remembers his father, whose body was never recovered from the sea.

Even if we dismiss supernatural explanations, several other options remain. Perhaps the father still lives, hiding in the house. Maybe Christian is insane and these things are mere figments. It’s strange that no one else is around to see them. Of course, one of the others could be gaslighting him, as the terms of his inheritance state he must be of sound body and mind on his rapidly approaching 25th birthday. After all, the plot shares remarkable beats with Gaslight (1940), the classic mystery in which a character inherits their childhood home and begins to question their own grip on reality.

This was Giancarlo Giannini’s debut, and he strikes a nice balance of mature confidence only just winning over a lingering adolescent awkwardness. Christian deliberately asserts himself upon the spaces he enters, altering them with action—hitting a light switch, opening a window, or simply lighting a cigarette. Yet his eyes often slide away from those of both Helene and Brigitte, who are deliberately presented to him, and the camera, to please the “male gaze”.

According to Gastaldi, he had the choice of filming in colour or covering Dominique Boschero’s fee. She was a star at the time, and he agreed with producers Mino Loy and Luciano Martino that such a low-budget piece of pulp needed a big name as a draw. She plays Helene as cool and tentative, but certainly confident about her cleavage.

Likewise, Brigitte is sexually bold, leaving lipstick prints on windows and dancing in lingerie for Paul, perhaps unaware that a voyeuristic Christian is watching. Later, she confesses her attraction to him and languishes before Christian wearing her skimpy cat-print bikini, which became a prominent piece of the film’s iconography. Mara Maryl designed and made all her own costumes; indeed, she was a creative collaborator throughout, having written the original story and co-produced the film.

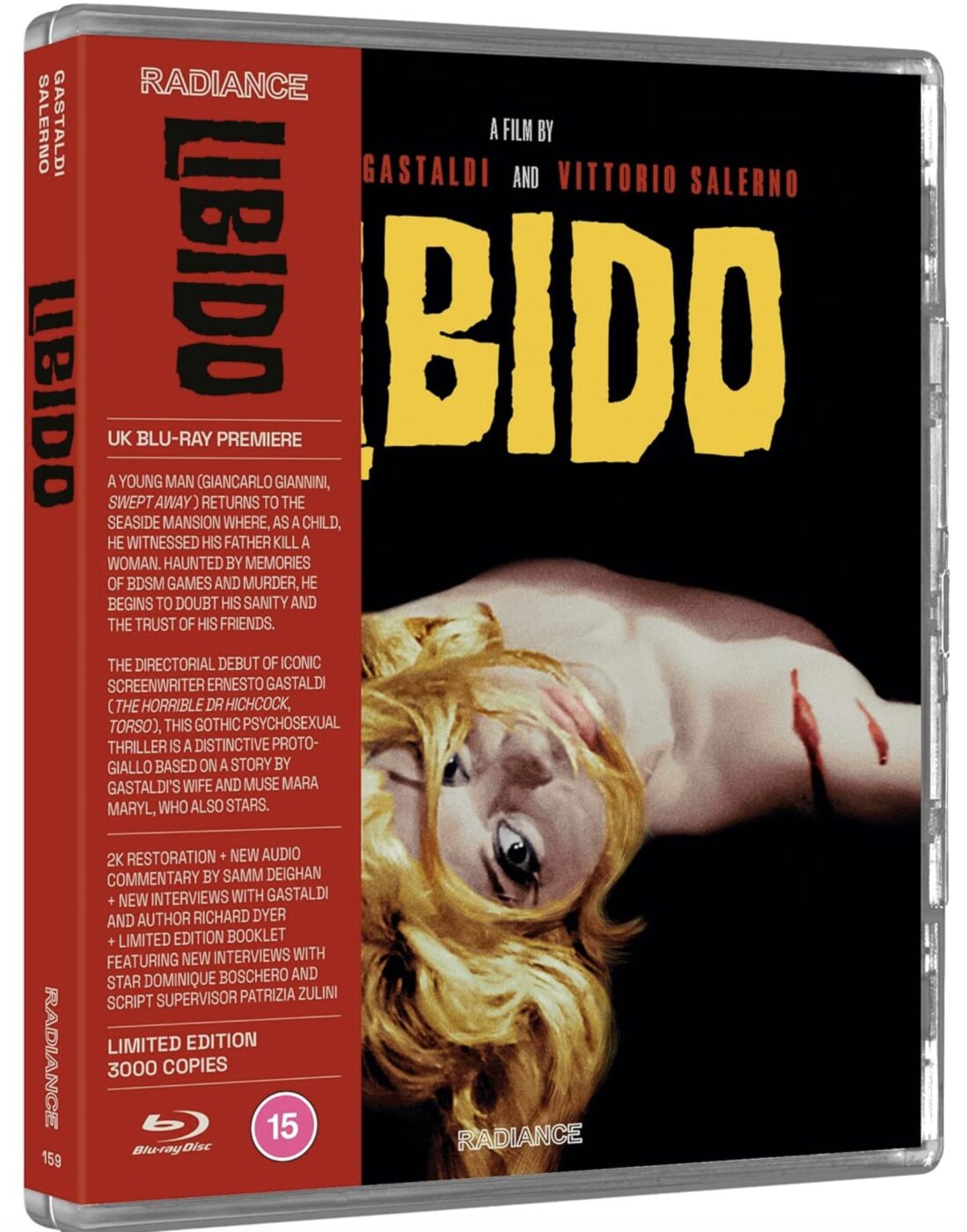

Mara Maryl was the soulmate and wife of Ernesto Gastaldi, and one of the reasons he would only take the director’s chair for another four features. They met while making the Gastaldi-penned Gold Fish and Silver Bikini (1961), in which she had a minor role. Apparently, she was heading for stardom, having turned down a role meant for Brigitte Bardot to appear in Libido; her character’s name is a little joke about this. Gastaldi was both flattered and grateful, and they made a reciprocal pact that he would only direct movies in which she starred. Later, when producers pressured him into casting a different lead actress, he pulled out of the project. Mara directed her energies to family life, and Ernesto never returned to the director’s chair, instead becoming one of Italy’s most prolific scriptwriters with another 100 credits to his name.

The four cast members work very well together; in such a small, intimate story, the unspoken reactions of one truly support the dialogue of another. I wouldn’t call these towering performances, but they are more than adequate to serve the story—especially given the schedule they worked to, often shooting into the early hours. Their enthusiasm and exhaustion brought a naturalism to what could’ve easily become baroque. They all remain slightly unconvincing, as required by a script that must arouse suspicions regarding each character. Surely, at least one of them is pretending to be what they are not.

Having contributed to more than 30 movies as a writer, Libido marked Ernesto Gastaldi’s directorial debut, sharing duties with fellow first-timer Vittorio Salerno. Gastaldi already had assistant director credits for the likes of Mario Bava. His opportunity to direct came about following a discussion with producers about how a novice could make a good movie with meagre resources if it were sufficiently narrative-driven. They called his bluff, assigning a tiny budget of 26M lira. That was approximately $15,500 in the ’60s—around $460,000 today. Gastaldi stepped up with gusto and stretched the funds to an 18-day shoot with a minimum crew and a cast of four.

Though the decision to film in black and white was financially inevitable, Romolo Garroni’s cinematography looks classy and, at times, almost painterly. In the night-time sequences, faces sometimes retreat into shadow as if being consumed by the darker aspects of the subconscious. Libido was a success and sold in more than 120 territories, earning around $400,000. Luciano Martino recognised the potential of dark thrillers and would produce several important gialli written by Gastaldi, including Umberto Lenzi’s So Sweet, So Perverse (1969) and the masterpiece The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971).

Back in the 1960s, experimentation with mind-altering drugs rekindled interest in psychoanalysis as a path to understanding psychedelic experiences. However, this Freudian method would soon be shunned as psychotropic pharmaceuticals pushed long-form treatment aside in favour of “quick-fix” medications.

Historians have conjectured that Freudian psychoanalysis was born in response to the oppression of the individual under far-right regimes in Europe. Possibly for related reasons, there is now a resurgence of interest in the field. In a recent article for The Conversation, Carolyn Laubender, a lecturer at Essex University, cites The Guardian and Vultureas declaring a psychoanalysis renaissance. Thus, Libido may again seem relevant, striking a chord with viewers amid the turmoil of contemporary society.

ITALY | 1965 | 90 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ITALIAN

directors: Ernesto Gastaldi & Vittorio Salerno.

writers: Ernesto Gastaldi & Vittorio Salerno (story by Mara Maryl)

starring: Dominique Boschero, Mara Maryl, Giancarlo Giannini (credited as John Charlie Johns) & Luciano Pigozzi (credited as Alan Collins).