BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1964)

A masked, shadowy killer brutally murders the models of a scandalous fashion house in Rome.

A masked, shadowy killer brutally murders the models of a scandalous fashion house in Rome.

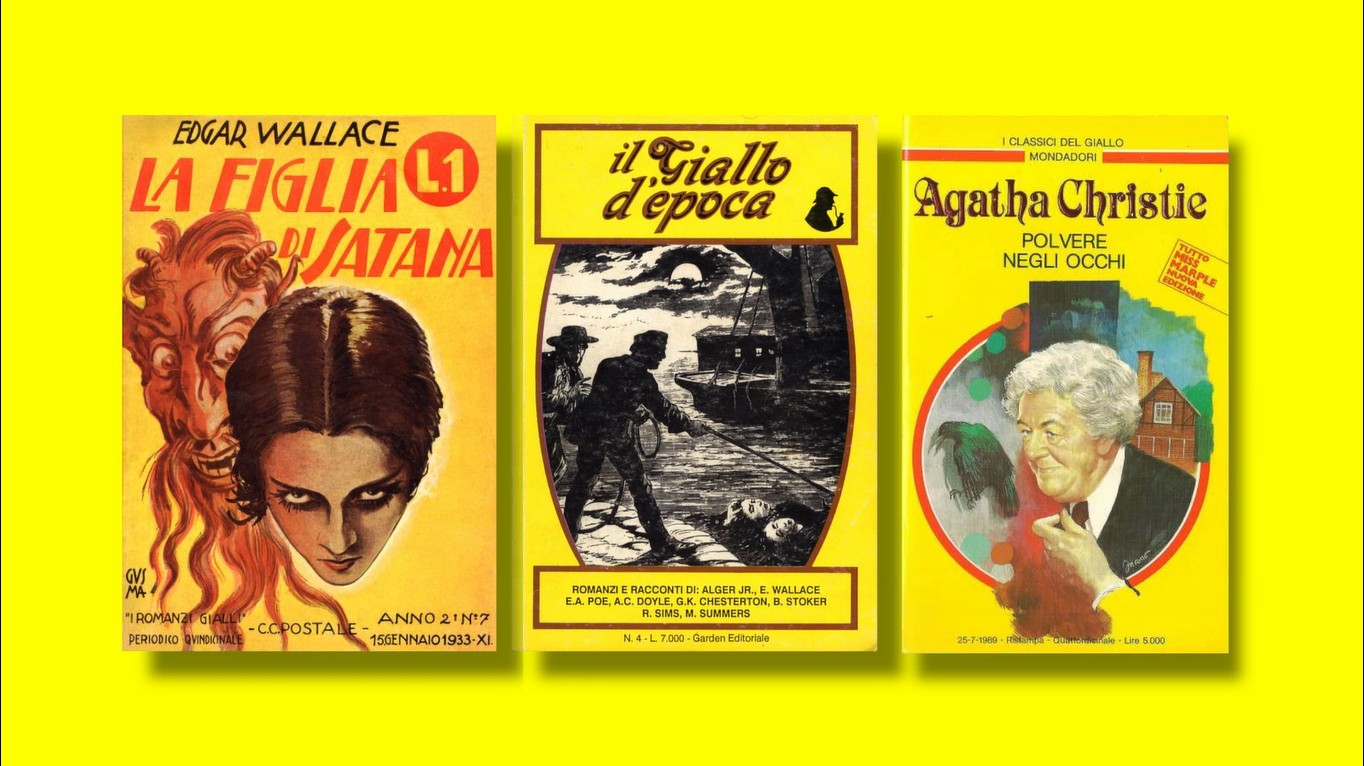

Anyone who enjoys a good giallo will be ecstatic about Arrow Video’s new release of Mario Bava’s Blood and Black Lace, uncut and lovingly restored using a 4K scan of the original camera negatives “in bleeding colour”, to go quote the English-language trailer. Made half a decade ahead of its time, some say this quintessential example is the progenitor of an entire genre that would dominate Italian cinema during the first half of the 1970s and remains relevant today.

Indeed, Blood and Black Lace introduced notable tropes and is a veritable checklist of what would become the defining features of the giallo. Although a precise definition remains hard to pin down, a giallo is simply a mystery thriller but tends to refer to highly stylised examples with elaborate plotting, ingeniously staged set pieces, and an aesthetic approach to bloody murder. Although I can think of better gialli made later, Blood and Black Lace ticks all those boxes and still ranks among the finest examples.

When I was discovering the genre back in the early-1980s, I never heard the word giallo. Such films fell under the umbrella of slasher movies or ‘video nasties’. Only in the last decade has this become a defined and much-discussed genre outside its native Italy and terminology like proto- and neo-giallo have entered the parlance of cineastes and critics. Bava’s Blood and Black Lace is now accepted as the genre’s first fully-fledged expression, although Bava’s previous thriller, The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963)—with its title overtly referencing Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)—sometimes vies for this distinction.

Speaking of Hitchcock, Psycho (1960) is often given credit for kick-starting the giallo as the first major movie to offer a reward of visceral violence at the climax of a slow-build suspense scene. It also staged its two stabbing scenes prominently as stylistic set-pieces that pushed a strongly gendered psycho-sexual subtext, particularly the game-changing shower sequence. Though it can be argued that Screaming Mimi (1958) had already broken that ground but proved to be ‘too much too soon’ for reactionary 1950s America, as Gerd Oswald’s noir proto-giallo was never given general release.

So, it was the success of Psycho that helped sell Blood and Black Lace to its investors and distributors, because if Hitchcock’s record-breaking box-office success was down to just two brutal murder scenes, surely a film promising six would be an even bigger hit. Continuing the collaboration begun on the screenplay for Black Sabbath (1963), Mario Bava tasked Marcello Fondato with drafting L’atelier della Morte / The Fashion House of Death, which was in production by the winter of 1963 and became Blood and Black Lace. The cast was dominated by fashion models whose faces would’ve been familiar at the time from the pages of magazines like Harper’s Bazaar and Italian Vogue.

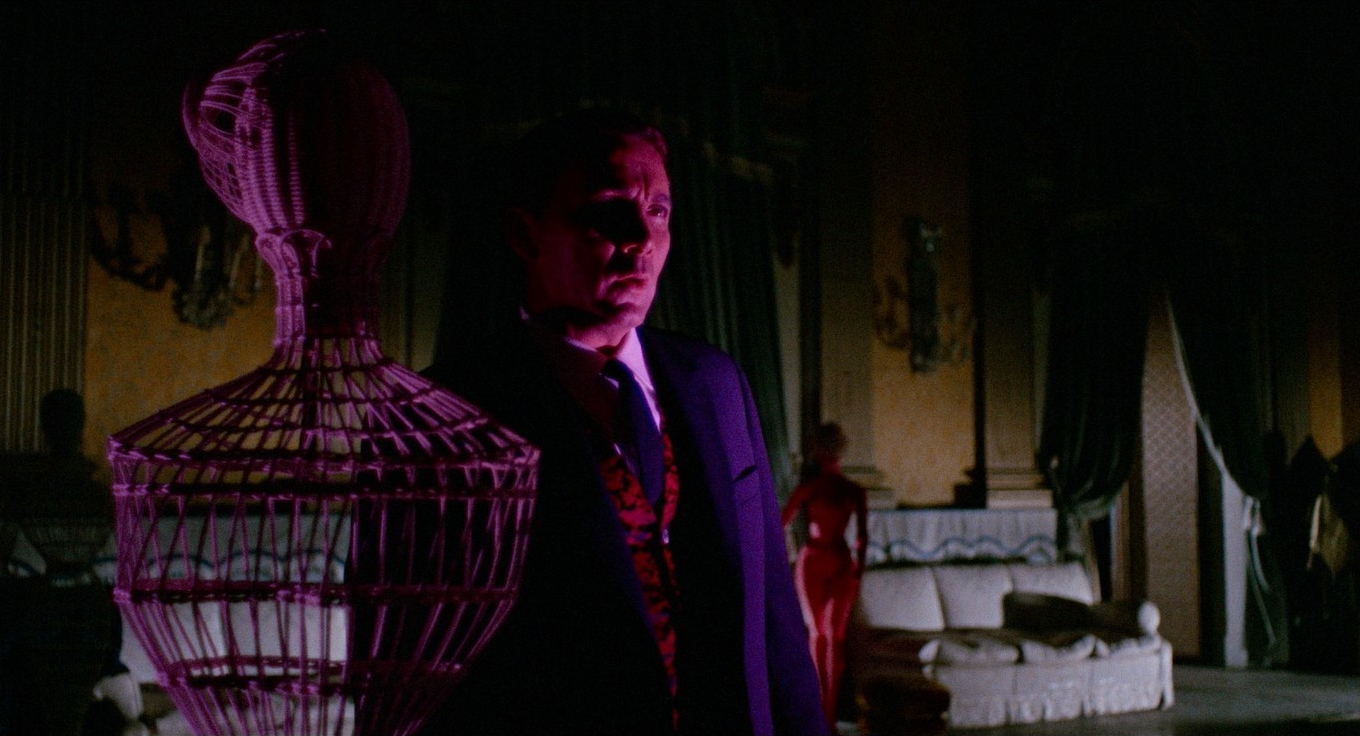

The striking use of lighting, creating strong contrasts of lurid colour, and deep shadow is the dominant visual feature—serving structural, expressive, and narrative purposes. The original Italian opening credits set the mood with saturated Eastmancolor hues of fiery red, electric blue, and sickly green—implying the heat of passion versus the cold calculating intellect, both tainted by envy or madness. Set to the moody jazz accents of composer Carlo Rustichelli, the sequence introduces the principal players in a series of individual vignettes and, if one is paying attention, serves as a menu of suspects and victims that can be counted off as the plot unfolds.

This approach is also suggested by the Italian title, Sei Donne per l’Assassino, which translates as Six Women for the Killer. Does this mean that, of these people, six will die and one will be the perpetrator? Already hinting at an Agatha Christie-style gathering of people within a contained environment and by a process of elimination—in this case quite literally for some—we try to work out who the killer may be just ahead of the final reveal.

In this case, the potential victims and suspects are mostly contained by the Christiana Haute Couture Fashion House, introduced with a visual gag that riffs on the famous crane shot in Citizen Kane (1941) that passes through the ‘El Rancho’ signage. Here, though, the storm-buffeted sign breaks and swings loose as we reach it. Visual humour aside, this serves to remind us that labels and signs are often artificial and tenuously attached.

We accept that this grand house (actually Rome’s famous Villa Sciarra) is a fashion house because we’re told it is. Likewise, we will make assumptions based on signifiers attached to the characters we are about to meet. The first snippet of conversation we eavesdrop on is Franco (Dante DiPaolo), who we learn is an antique dealer, pleading with fashion model Nicole (Arianna Gorini) to source him some cocaine… There’s fun to be had keeping track of plentiful clues, none of which are quite superfluous enough to be called red herrings.

The colour red, however, is used as a linking device between scenes and characters and generally foreshadows violence and death. Take note of who does and doesn’t use the telephones with red handsets, for example. This is a trait that Dario Argento, among others, would pick up and recycle several times in his seminal gialli, for the use of red suggests blood, even when there is none.

Isabella (Francesca Ungaro), the first of the six women to become victims, wears a shiny blood-red raincoat as she briskly walks through a long arbour on her way to the fashion house. A scene that evokes the fairy tale peril of Little Red Riding Hood and will be visually quoted by Dario Argento in the opening of Suspiria (1977). But before reaching some shelter, Isabella is set upon by a trenchcoated figure wearing a wide-brimmed hat, stocking mask, and black gloves.

The assault is swift, brutal, and deliberately eroticised with dishevelment designed to reveal glimpses of lingerie and stocking tops. There’s nothing shown that hasn’t been normalised in glossy fashion magazines but effectively disturbing here as the model is concussed against an abrasive tree trunk and garrotted until her lifeless body is little more than a mannequin, dragged off into the shrubbery. Strong stuff for the early-1960s, and the recurring gendered violence may still prove problematic for modern audiences.

In his commentary, Bava biographer Tim Lucas connects the sexualised violence of Blood and Black Lace to the personal and political backdrop of Italy as described in The Italians: A Full-Length Portrait by journalist and cultural commentator Luigi Barzini, published in 1964. The post-war libertine attitudes had led to a faster turnover of relationships and the ensuing jealous frustrations sometimes inflamed violent reactions. Men’s masculinity was being challenged and many overcompensated with performative machismo that women felt the brunt of. It wasn’t uncommon for men to murder adulterous wives in ‘crimes of passion’.

Tim Lucas also suggests the Swedish thriller Mannekäng i Rött / Mannequin in Red (1958) was a significant influence, with its similar plot elements including blackmail and murder in a fashion house. The title conjured an uncanny image from my memory of a woodland scene featuring a freakish mannequin consisting of the lower half of a female, just legs and a partial torso, mirrored by the top half, with a second set of legs reaching upward instead of arms. It seems a flimsy frock is discarded at this figure’s feet, and it now wears only two pairs of shiny shoes and ankle socks. In the background, partly concealed behind a tree, lurks a more menacing figure dressed in a dark trench coat. This sinister image, perfect for a giallo movie poster, was created in the 1930s by Hans Bellmer and in some hand-coloured prints, the mannequin is, indeed, red. The Surrealist photographer often positioned these life-size dolls in familiar settings suggesting psychologically disturbing narratives.

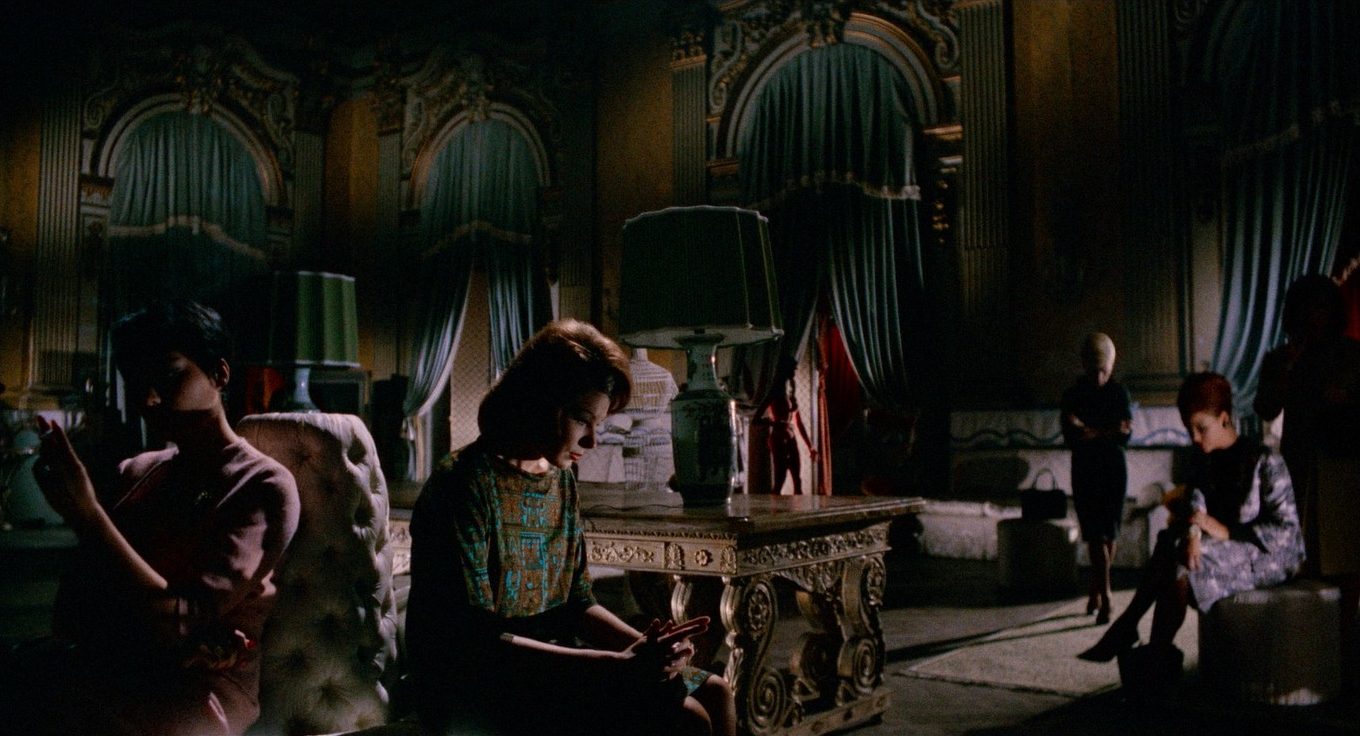

The Surrealist obsession with existentialism and how inanimate objects can suggest living things produced many works of so-called Organic Surrealism, blurring the representations of life and death. Automatons, dolls, and marionettes are treated in a visually similar way to living humans and vice versa… Throughout Blood and Black Lace, Bava cuts from shots of murdered women to Romanesque fountains and statuary, or tailors’ dummies, emphasising the transition from a person into an object. Living flesh becomes dead meat.

Inside the warm classical interior of the Villa, more models gather among many more mannequins in preparation for a fashion show. A juxtaposition that prompts us to consider the differences between a lifelike dummy and a lifeless body. In turn, encouraging a debate regarding the objectification of women by advertising in general and the fashion industry in particular. Perhaps, also, disquieting thoughts may arise concerning our own mortality…

Bava’s eroticism of violence can also be interpreted as a survival of innocence. After death, the women are presented in flattering poses and despite their injuries, their beauty is partially restored. They have been defiled by evil, but they did not become evil. They are victims, not only of the violence but of the culture—they were models for fashion, objectified forms to show off commercial items, that enveloped them and negated their individuality. Even in life, their value was reduced to that of moving mannequins. Dehumanisation enables inhuman acts, does it not?

Inspector Silvestri (Thomas Reiner) arrives at Christiana’s to investigate the murder and so we get the gathering of potential suspects at the top of the story instead of waiting for the denouement. The fashion house is managed by Contessa Cristiana Cuomo (Eva Bartok), a fresh and wealthy widow, and her business partner Massimo Morlacchi (Cameron Mitchell). Cesare (Luciano Pigozzi) is their resident dress designer, who may be ‘in the closet’ as a homosexual, and looks so much like Peter Lorre it took a couple of scenes to remember he wasn’t. Marco (Massimo Righi) is sweaty, nervous, apparently obsessed with Peggy (Mary Arden) and, along with a red mannequin, we definitely saw him popping pills. And then there’s the ensemble of young, elegant models… The entire cast is perfectly capable, even those who weren’t professional actors and must rise to the challenge of physically demanding scenes.

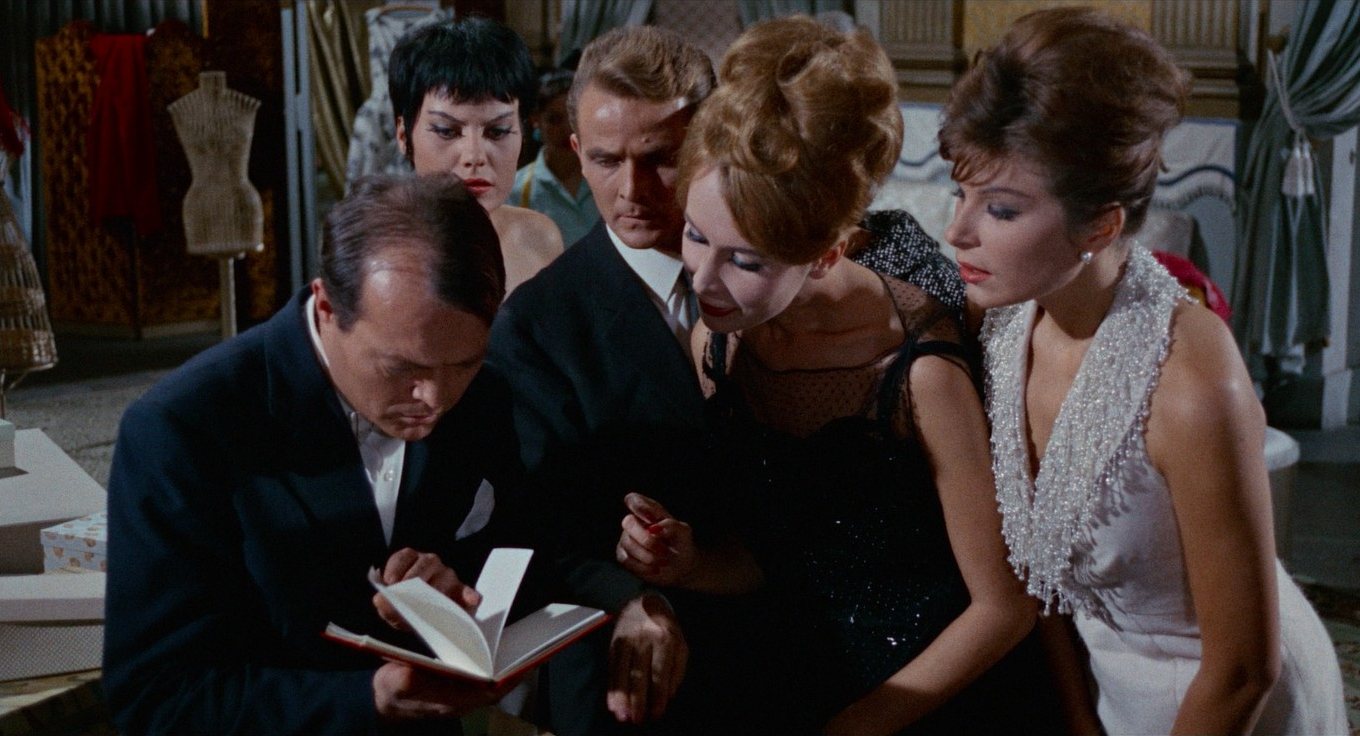

Only after the Inspector has conducted his initial interviews and left does Nicole, whom we overheard discussing cocaine earlier, go through Isabella’s personal effects and find a red, leather-bound diary. That colour code again. Could it contain any clues as to the identity of her killer? The interest of everyone present is piqued by this discovery and it seems they all want a peek at its pages.

As Nicole shared a house with Isabella, the diary is entrusted to her safekeeping, and she promises to deliver it to the police in the morning. However, during the fashion show, her handbag is left unattended, and the contents pilfered by fellow model Peggy. It turns out Isabella could’ve jotted down incriminating details about more than one of her colleagues, including their drug habits and several sexual indiscretions. Clearly, there’s some fear in the room that it may contain information that a potential blackmailer would relish.

Between the inventively staged murders, the plot relies on several surprises, and at least two major twists. One of which I believe to be a cinematic first, though has been employed in several thrillers since, and possibly inspired by a piece of lore surrounding the historical case of Jack the Ripper. So, it’s difficult to discuss some of Bava’s stylistic and narrative innovations without spoiling the fun and, as I hope this gorgeous print will attract fresh viewers, I’ve avoided significant spoilers. Suffice it to say, this is a must for any giallo enthusiasts and film historians interested in the development of the murder mystery thriller.

There were killers who wore gloves in earlier thrillers, including I Vampiri (1957), another serial killer proto-giallo which Bava also had a hand in (pun intended), sharing the directorial duties with Ricardo Freda. But it’s Blood and Black Lace that established the trope as a giallo signifier. Other movies apart from Psycho and Screaming Mimi had eroticised murder to varying extents, the most notable example being Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) an innovative British thriller that pre-empted Psycho by three months or so. Powell had used expressive colour and even featured a portentous red dress. Like Psycho, it controversially explored obsession and psycho-sexual malaise as motives for murder but perhaps pushed the envelope too far for the time and was banned or derided as filth in many territories.

Likewise, Blood and Black Lace may’ve crossed similar lines and it wasn’t well received. With a limited initial release, it took just $77,000 at the Italian box office, falling short of its budget, estimated to have been over $100,000, making it one of the least successful films of Bava’s entire career. It was released in various cuts and under different titles in different territories and fell into obscurity for decades.

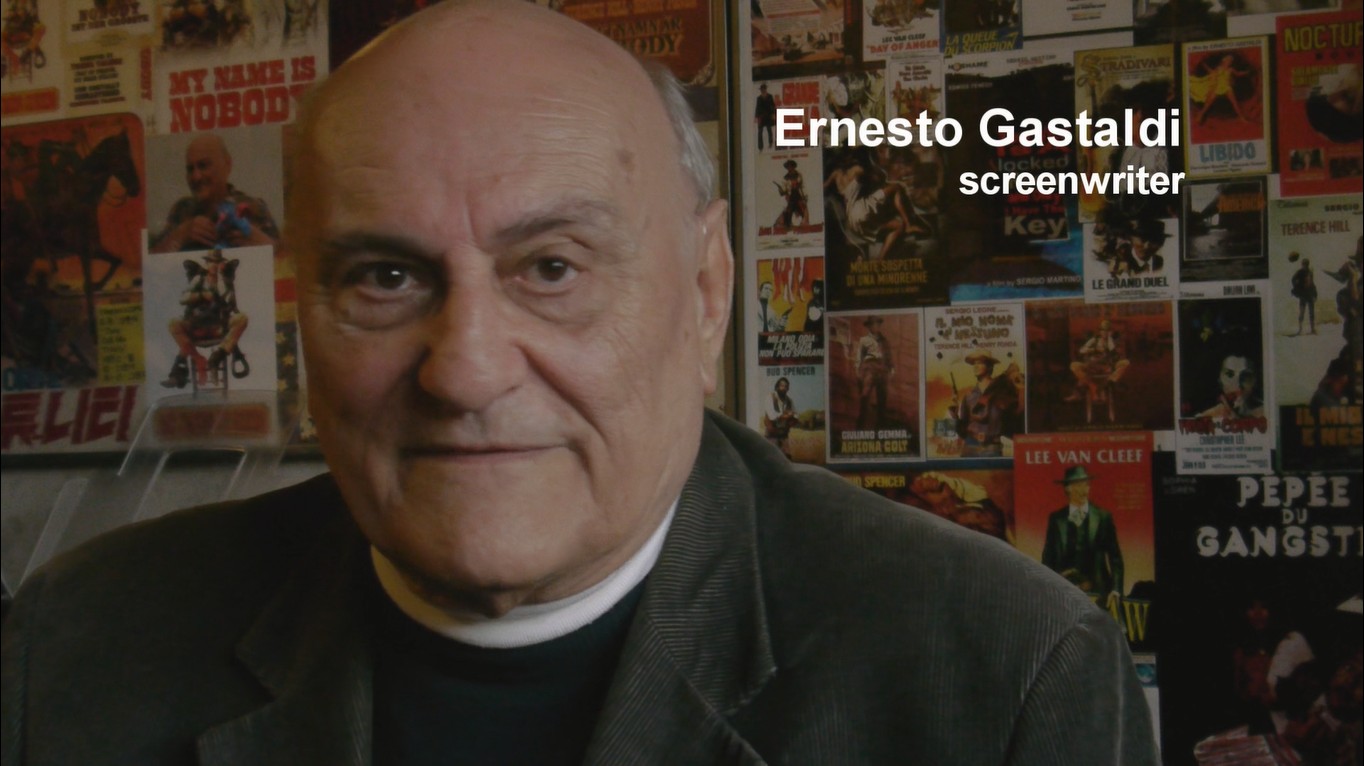

However, by the advent of the home entertainment market, it had accrued semi-mythic status and the first VHS releases rapidly sold out, failing to sate demand regardless of the poor transfers of incomplete versions. In 1997, Quentin Tarantino attempted to release a reconstructed version but was unable to source prints of sufficient quality. A 2K scan of the original camera negatives was supervised by the saviour, Tim Lucas and released by Arrow, in 2015. And now this latest release from Arrow Video is taken from a new 4K scan of those original camera negatives, with the addition of the Italian opening titles that set the scene so well. Finally, ‘all present and correct’, as Bava intended.

ITALY • FRANCE • WEST GERMANY | 1964 | 89 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN • ENGLISH

Newly restored from the original camera negative and presented here in its original uncut form, this new release allows fans to see Blood and Black Lace afresh and offers newcomers the ideal introduction to a major piece of cult filmmaking. Offered as a 4K Ultra HD Limited Edition Blu-ray and Limited Edition Blu-ray.

director: Mario Bava.

writers: Marcello Fondato, Mario Bava.

starring: Eva Bartok, Cameron Mitchell, Thomas Reiner, Claude Dantes, Dante Di Paolo, Mary Arden & Luciano Pigozzi.