THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME (1923)

In 15th-century Paris, the brother of the archdeacon plots with the gypsy king to foment a peasant revolt. Meanwhile, a freakish hunchback falls in love with the gypsy queen.

In 15th-century Paris, the brother of the archdeacon plots with the gypsy king to foment a peasant revolt. Meanwhile, a freakish hunchback falls in love with the gypsy queen.

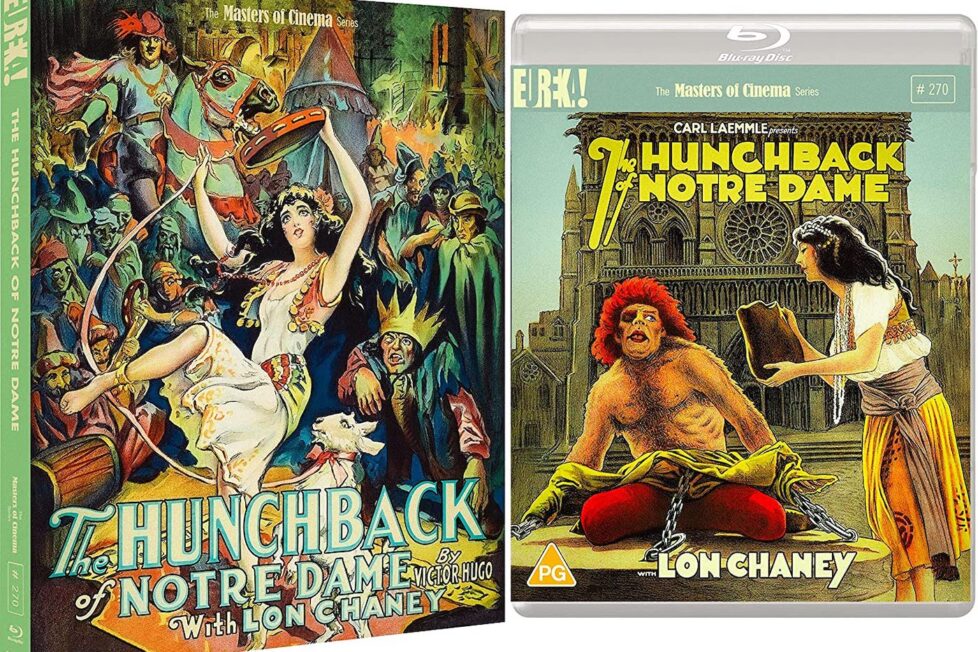

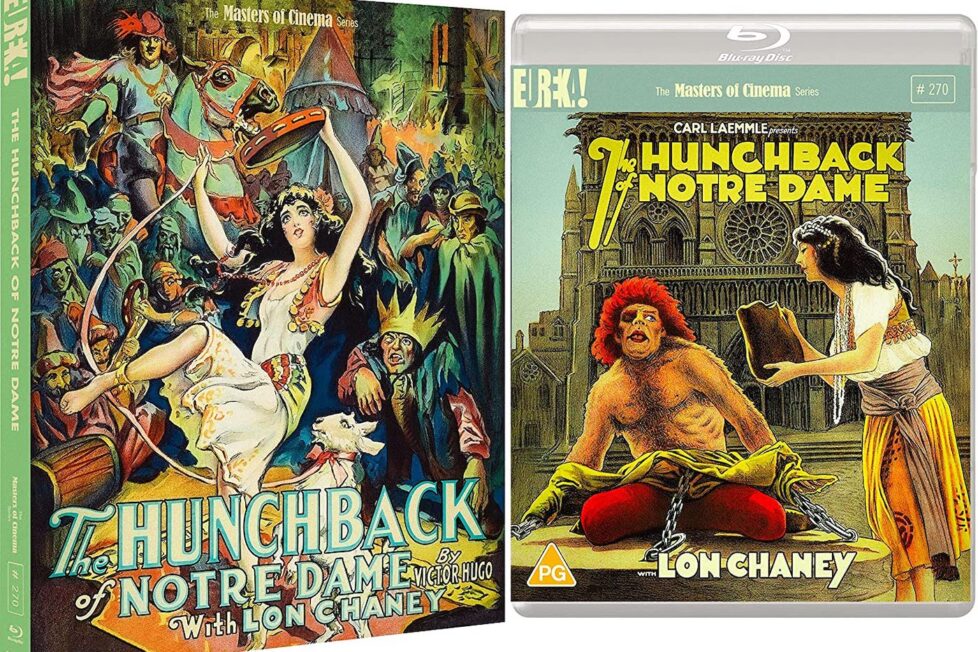

Modern audiences may approach this classic version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame in a variety of ways: film buffs will be aware of its legacy as the film that templated the very idea of the Hollywood blockbuster, while horror fans will enjoy seeing one of the earliest expressions of the genre and appreciate its Gothic tones, presaging the 1930s Universal monster movies. Aficionados of the silent era will revel in its exaggerated theatrics and extravagant production design. Hopefully, some will come to this faded masterpiece with fresh eyes, enjoying the midnight movie mood as ideal Halloween viewing… And now they can, thanks to its timely UK Blu-ray debut as the latest title in Eureka! Entertainment’s ever-growing ‘Masters of Cinema’ catalogue.

When taken in context, as a film made a century ago, none could fail to be in awe of its epic achievements. It was what Universal Pictures called a ‘Super-Jewel’, which was a new category of movie made on budgets approaching or exceeding a million dollars. The Hunchback of Notre Dame began with a budget of around $1.250M dollars and has been estimated to have cost closer to $2M all-in, with the sets and props alone racking up $500,000. That was a huge commitment back then but it paid off in revenue rapidly exceeding $3M dollars. It remains Universal’s most lucrative silent film and set Hollywood on the path that’s led us to the blockbusters with budgets now approaching or exceeding a billion dollars.

Having said that, it is incredibly dated, made at a time when cinema was still exploring the potential of what a feature film could even be. Despite rumours of a complete print, archived somewhere in Russia, it’s accepted the ‘Director’s Cut’ of the film is now lost. The original duration, as screened at its big city premiers, is recorded as being 133-minutes which then had a good 20-minutes shaved off for general release. Those prints were worked hard in the regional picture houses, and none survived. The best existent version is this 4K restoration by Universal Pictures, struck from two different 16mm prints. Luckily, one of those retained the original colour tints and, when combined, offer us the best quality possible.

However, these ‘show-at-home’ editions were further edited to 100-minutes, toning down the violent imagery and that becomes obvious when scenes jump or end abruptly. Presented on Blu-ray, the 4K scan brings out all the surviving details down to the film grain, which includes plenty of scratches and other irreparable artefacts. But, for me, this only adds authenticity and helps conjure its creepy vibe.

It also reminds viewers that what we’re seeing is a piece of cinema history that doesn’t adhere to later conventions. Although eminently appropriate for the story of a profoundly deaf character, the silent format encouraged overly expressive performances. For the most part, what we get is a form of mime, rather than acting, which can appear inappropriately comedic at times. Revolting peasants jumping up and down like excited children with their burning torches just look silly, but I guess not all of the 2,500 extras could be trained actors! The main cast all step up with passable performances but are all overshadowed by Lon Chaney as Quasimodo, the titular hunchback.

In Victor Hugo’s historical novel, originally published in 1831 as Notre-Dame de Paris, 1482 / Our Lady of Paris, 1482, he was just one in an array of picaresque characters telling their entwined tales with the great Gothic cathedral as the constant backdrop. It’s Lon Chaney’s bravura rendering of the role that made him the ‘backbone’ of this version and had such an impact on audiences at the time, ensuring the character’s now legendary status. The Hunchback of Notre Dame has since entered the public consciousness through so many screen adaptations of which this 1923 version is by far the most significant, if only for setting the dramatic bar for subsequent sound versions to meet.

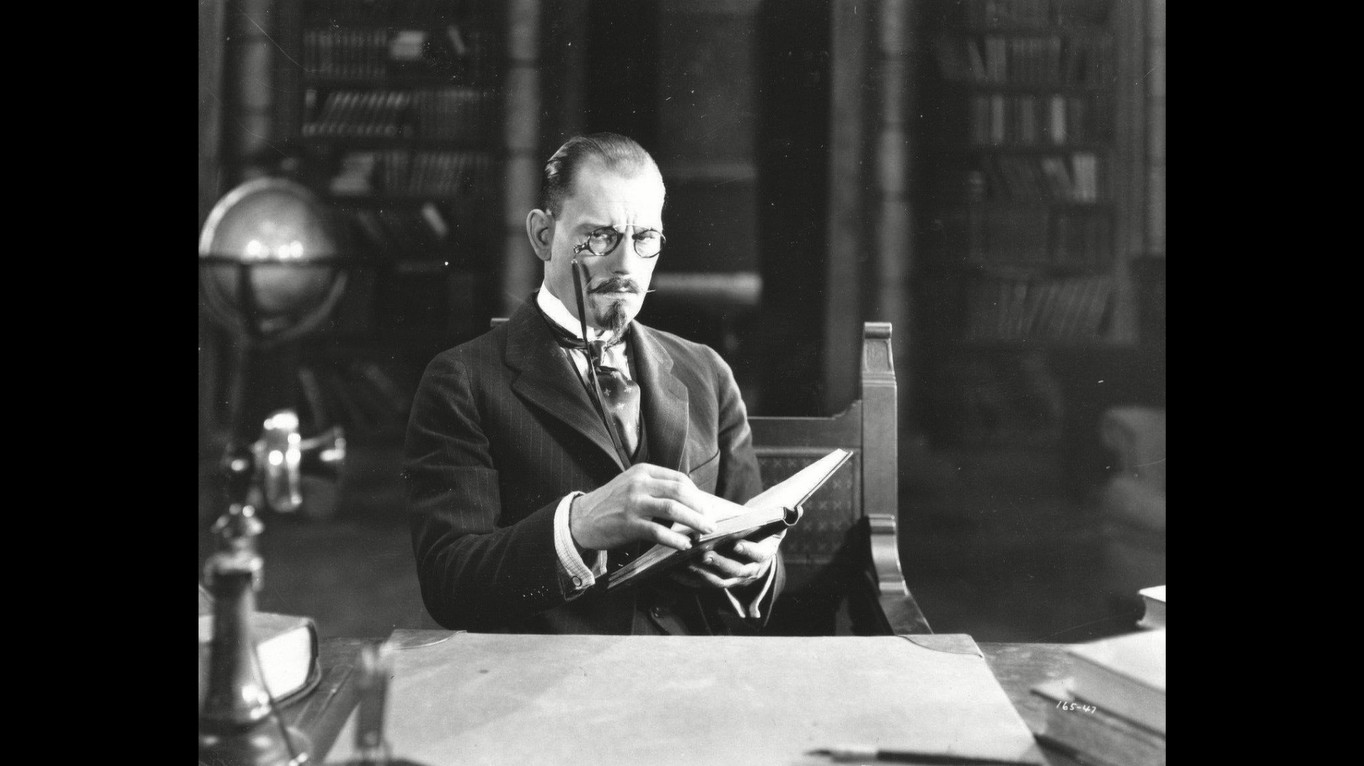

Driven by a desire to showcase his skills in the role of Quasimodo, The Hunchback of Notre Dame was really Chaney’s baby from the start. He already earned a reputation as the go-to guy for any sort of unusual part requiring transformative makeup, a skill he’d taught himself to get parts no one else could. In the early days of his career, he would wait with those hoping for work as extras and respond to casting calls no one else stepped forward for. It was his breakthrough role in The Miracle Man (1919), as a cripple who had to be healed in-camera, that gained him respect as a gifted actor. After that, he landed a string of starring roles and earned himself the moniker ‘The Man of a Thousand Faces.’

Chaney acquired the rights to Hugo’s novel in 1921 and touted it around a few studios, including some in Europe, managing to secure a deal with short-lived Chelsea Pictures the following year who announced that Alan Crossland would direct. Nothing came of that, except to attract the attention of Irving Thalberg who was making his name as the dynamic and uncompromising young studio manager at Universal. Thalberg soon convinced studio founder, Carl Laemmle to take on the project. Although Laemmle steered the production, it’s generally accepted that Lon Chaney retained artistic control throughout.

He was known to direct his own scenes but had approved the somewhat prosaic Wallace Worsley as director, having already worked with him on The Penalty (1920), The Ace of Hearts (1921), Voices of the City (1921), and, most notably, A Blind Bargain (1922). The latter starred Chaney in a dual role as a mad doctor and as a hunchback that, in hindsight, can be seen as a trial run.

Chaney oversaw the development from script to screen, collaborating with writers Perley Sheehan and Edward Lowe in daily script meetings. The final version they came up with remains true only in essence to the source material, with character attributes swapped and shared among the cast.

Hugo’s original novel is a huge sprawling mess of a story framing a political treatise on Parisian history and the architecture of the cathedral, which has entire chapters dedicated to it. If anything, Esmeralda is the star of the book acting as a catalyst for all sorts of dark deeds and desperate desires. Her innocence inspires evil in the men around her except for Quasimodo, in whom she inspires courage and compassion. To be honest, I’ve never made it to the end of the novel, but I think the same can be said of the characters who nearly all meet a tragic demise. Although the film’s denouement is certainly tinged with tragedy, it’s a different and much happier ending… for most of them.

As a baby, Esmeralda (Patsy Ruth Miller) was snatched from the home of a noblewoman who, driven mad by the loss, sought refuge as the manic nun, Sister Gudule (Gladys Brockwell). She’s installed in a spartan cell overlooking the cathedral square where she rants racial hatred for the gypsies she blames for stealing her child. At the annual Festival of Fools, Clopin (Ernest Torrence) the self-proclaimed King of the Beggars lays on a show and presents the gypsy dancer, Esmeralda, a foundling he’s raised as his own daughter who now becomes the focus of Gudule’s scorn. The reveal that they’re mother and daughter is held back to maximise the inevitably tragic consequences.

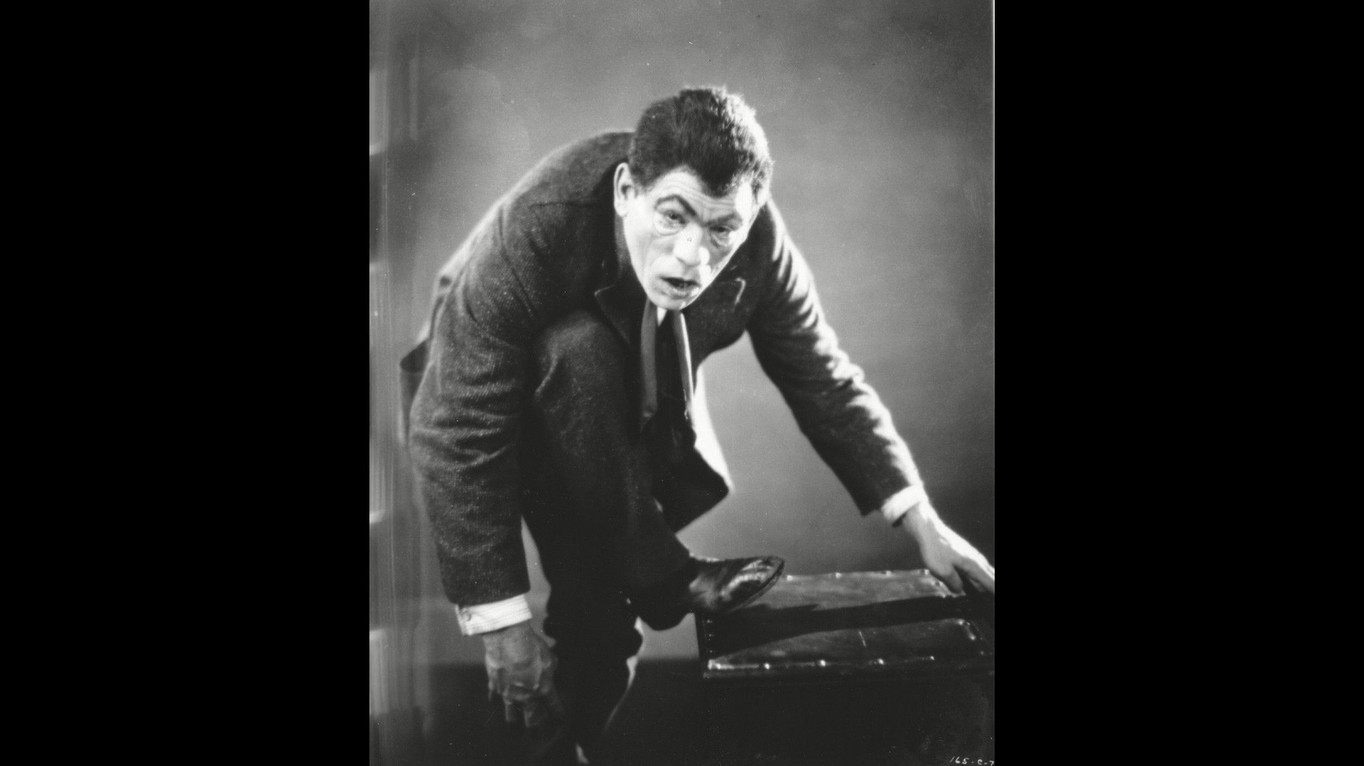

We first see Quasimodo in a contemplative mood among the gargoyles he resembles but he soon responds to the jeers of the gathering crowds with an acrobatic display whilst directing uncouth gestures at those below. Later that evening, as the most grotesque man in Paris, he’s crowned ‘King of the Fools’ and comes face to face with Esmeralda. She doesn’t manage to conceal her revulsion and we can tell the hunchback is hurt by this sadly predictable response.

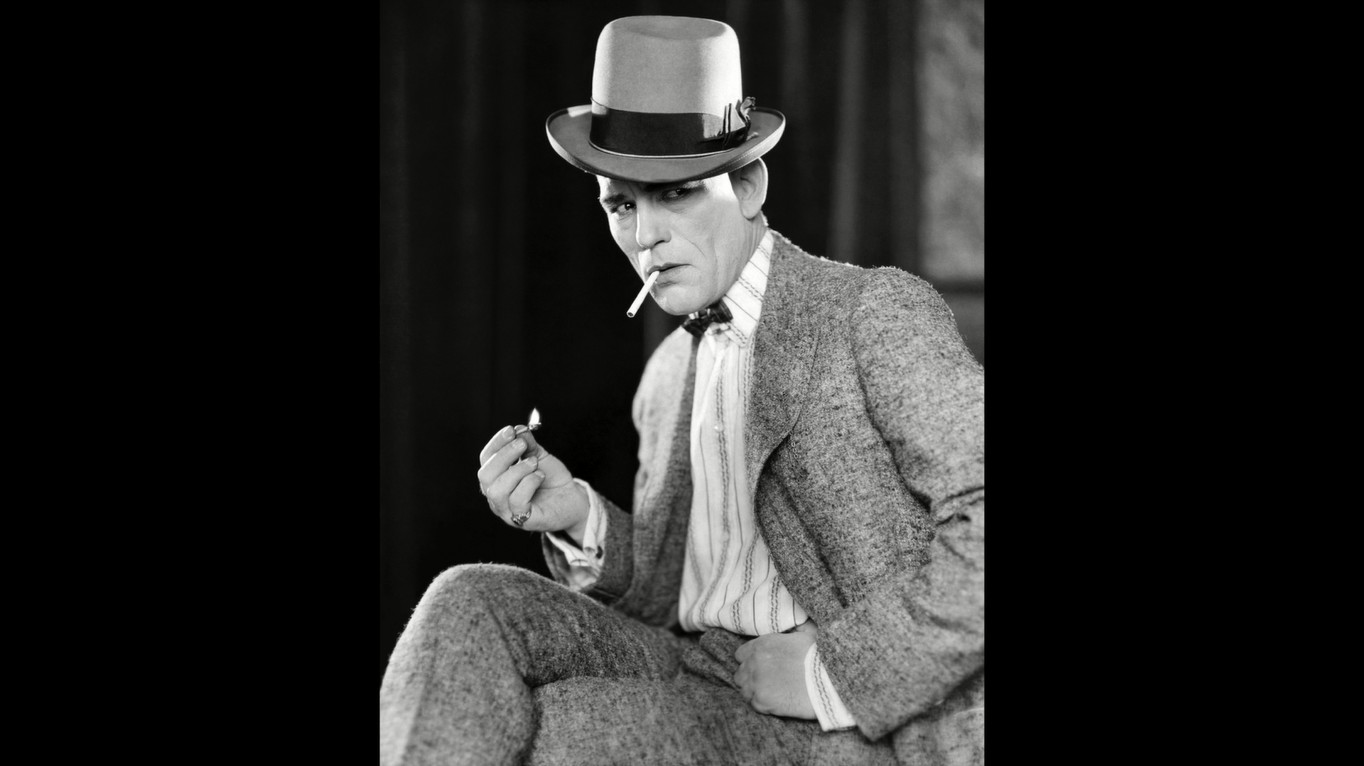

Quasimodo isn’t the only one to be entranced by Esmeralda’s youthful beauty. Phoebus (Norman Kerry), a dashing captain in the King’s Guard is also smitten, as is Jehan (Brandon Hurst) the wayward brother of the cathedral’s Arch Deacon, Don Claudio (Nigel de Brulier). Now, this masculine triad are the characters most changed from the novel, in which the Arch Deacon is the main villain and Phoebus is a manipulative philanderer. Here, Phoebus transforms into a traditional leading man, changed by the love of a good woman, and Don Claudio is a paradigm of pious principles. All the villainous duty now falls to Jehan, a role relished by Brandon Hurst who turns in a strong supporting performance but one he would surpass as the villain in another, far superior, Laemmle-helmed adaptation of a Victor Hugo novel, The Man Who Laughs (1928), directed by Paul Leni.

It’s Jehan who commands Quasimodo to abduct Esmeralda, leaving him to take full blame when caught by Captain Phoebus. With the intervention of Don Claudio, Quasimodo’s sentence is reduced to public flogging. This key scene really shows off Lon Chaney’s full-body prosthetics and gives the story its moral core. Esmeralda is the only one to show the hunchback any kindness, bringing him water and helping to loosen his chains, even though she knows he was her abductor.

It’s an embittered Jehan who then manipulates public fears and racial tensions, accusing Esmeralda of witchcraft on the grounds that she’s both a gypsy and has trained her pet goat to dance. His plans to rescue her from a death sentence, so she’d be indebted to him, are thwarted when Quasimodo returns her kindness by bravely coming to her rescue, claiming sanctuary in the cathedral. I need say no more, as I’m sure the basic plot is familiar, if only from the popular 1996 animated Disney version!

Although the cast is given adequate screen time, Lon Chaney inevitably steals the show. A remarkable performance indeed, Quasimodo was his career benchmark but it’s not his subtlest. He only really manages to make emotional contact with the viewer a couple of times, though he does make those count. I’ve only managed to watch a handful of his more than 160 appearances, but I believe he outdid himself at least twice—in the consecutive roles for He Who Gets Slapped (1924) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), which was the pinnacle of his achievements. Even though he’s fully masked for most of the movie it’s one of the greatest, most emotionally eloquent, performances of the silent era. His physical acting was second to none, a talent he attributed to being raised by deaf parents with whom he learnt to communicate through sign language and gestures.

The real stars of the Hunchback of Notre Dame are the amazing sets. They finally covered nearly 20 acres—an area more than 10 football pitches large—and were built over six months in the San Fernando Valley backlot that became known as Universal City. Sets were still under construction as shooting began but, being a silent movie, the noise was not too much of a problem. Though, due to the sheer expanse, it was the first production to use radios and an electronic public address system to marshal the small army of cast, crew, and the thousands of extras needed for the epic scenes.

The cathedral looks terrific on screen and seems impossibly imposing, particularly its detailed façade rising into the night sky during the finale. Surely even with the time and budget, they couldn’t have built those towers to their full height of nearly 70 metres? No, they’re extended and made to look all the more impressive with clever use of glass paintings and ‘floating miniatures’ suspended much closer to the camera. Here, the illusion is seamless with lighting and perspective perfectly matched. It’s a fine early example of the technique that Hollywood would come to rely on until the 1980s when electronic compositing offered a cheaper, usually tackier, alternative. Optical effects were supervised by Friend Baker and Phil Whitman, overseen by art directors Sidney Ullman, and Elmer Seeley, who’d just worked with Norman Kerry on Merry-Go-Round (1923) and went on to work with Lon Chaney again on The Phantom of the Opera (1925) and later contributed to The Wizard of Oz (1939).

Robert Newhard’s cinematography is another stand-out feature, making the most of the immense sets whilst handling deep shadow and brightly lit patches, and selling us the forced perspectives of trompe l’oeil backdrops—often in a single shot. It seems the framing of the set design dictated much of the composition, making the stone seem solid and eternal whilst fleeting human action rushes through or across the scene. It’s difficult to know for sure given the quality of the surviving prints, but I imagine the fabric textures would’ve been celebrated—the embroidery worn by the fine folk and the coarse filthy fabrics of the ruffians. Reputedly, Universal’s costume department dedicated weeks to making something like 3,000 different costumes and combinations for the production, with the bulk of them inspired by French Romantic paintings.

On release, the film met with unanimously positive reviews, wowing audiences with its high production values along with Lon Chaney’s brute physicality, and unprecedented prosthetics. It was hailed as the single greatest screen performance of its day. His death-defying acrobatics, leaping across the façade of the cathedral, climbing pillars, and swinging from the gargoyles, had audiences gasping. Although he’s not actually that high up, it’s certainly impressive, especially when you know he was wearing a heavy costume plus 6kg of hump. Though I hope, for safety’s sake, he dispensed with the straps and braces that twisted his legs and are said to have left life-long damage to his joints.

Despite radically distorting his face with wadding, putty, false teeth, and a big fake wart closing his right eye, Chaney does manage to act using his whole posture and just one eye. It could be seen as a kind of precursor to John Hurt’s performance as Merrick in David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (1980). Likewise, Chaney manages to let the humanity show through, eliciting pathos rather than fear, even though his Quasimodo is said to have terrified children and is often discussed as the first of Universal’s famous monsters.

USA | 1923 | 100 MINUTES | 1.33:1 | BLACK & WHITE (TINTED) | SILENT (English Captions)

director: Wallace Worsley.

writers: Perley Poore Sheehan, Edward T. Lowe, Chester L. Roberts; based on the novel by Victor Hugo). (Uncredited: Lon Chaney & Irving Thalberg).

starring: Lon Chaney, Patsy Ruth Miller, Norman Kerry, Ernest Torrence, Kate Lester, Winifred Bryson, Nigel de Brulier, Gladys Brockwell.