THE ELEPHANT MAN (1980)

A Victorian surgeon rescues a disfigured man who's been mistreated while scraping a living as a carnival freak.

A Victorian surgeon rescues a disfigured man who's been mistreated while scraping a living as a carnival freak.

It’s hard to imagine Mel Brooks—the director of broad, slapstick comedies like Blazing Saddles (1974) and Young Frankenstein (1974)—sitting down to watch David Lynch’s surrealist body-horror Eraserhead (1977). It’s harder still to imagine Brooks loving the work so much that he’d agree to let the fledgeling director helm his next production: an austere, high-brow period drama called The Elephant Man.

But it’s rather in keeping with The Elephant Man’s themes of expectations and perception that two unlikely artists should collaborate on such a film, and prove there are shades to them not immediately apparent.

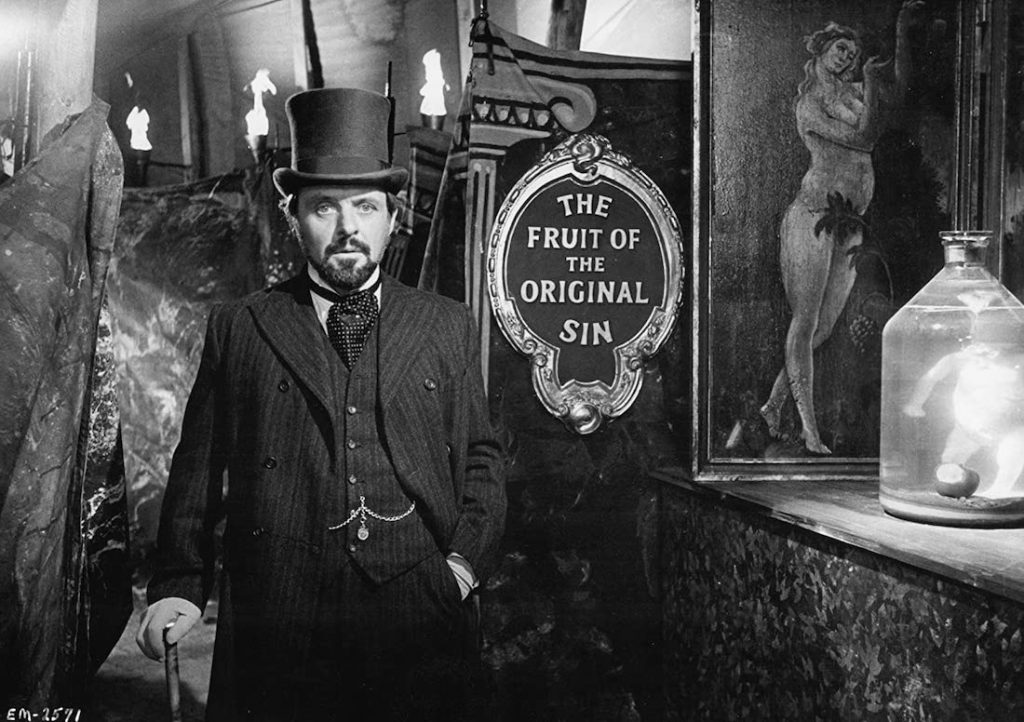

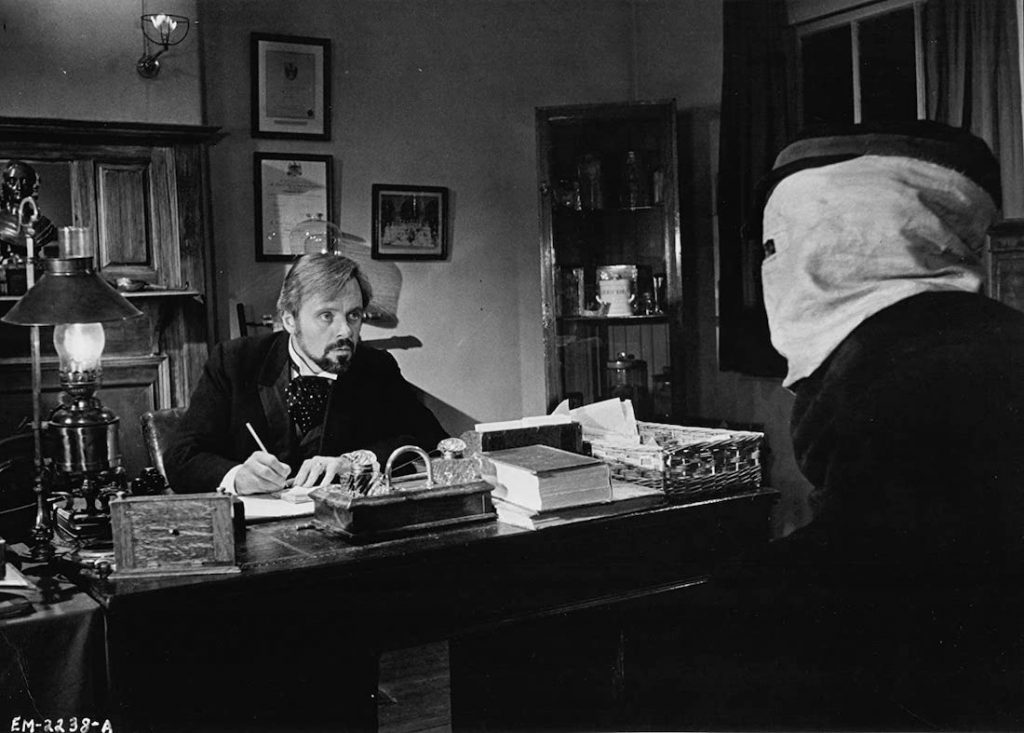

The story, set in Victorian London and loosely based on a true story, follows John Merrick (John Hurt), cruelly dubbed ‘the elephant man’ for his physical deformities, as he’s passed around the rungs of society—first as a freakshow attraction, then as a medical anomaly. Esteemed surgeon Dr Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins) then attempts to restore Merrick’s dignity, but the tension of the movie simmers with the question of what Treves ultimately stands to gain from Merrick. Are his intentions to provide Merrick with the life he should always have had, or does he have that most Victorian of intentions: to conquer something nobody else has?

When we meet Treves, he’s cloaked in shadows like a silent film villain, pushing through the rotten back alleys of London. He’s refined, well-kempt, and seemingly wouldn’t be in a place like this if he didn’t have a good reason. As he stumbles further into the bowels of a dank freakshow, where the degradation of human life is a business, he finds what he’s looking for… and all he can do, in astonishment, is weep. It’s Hopkins’ finest moment in the film and a neat directorial choice by Lynch. What are we not being shown that could cause a man to weep?

The Elephant Man holds off on revealing Merrick for much of its first act. In monster movie tradition, audiences are teased with the looming promise—or threat?—of a good look at the “creature”. In King Kong (1933), t’s not until the heroes have pushed through the darkest jungle that you meet the eponymous ape, allowing an audience time to build an image in its head and let collective imaginations run wild.

But The Elephant Man is not about a monster. And the use of silhouettes, shadows, and hoods to obscure Merrick from view isn’t a cheap trick. Instead, any fear is deflated when we meet him and realise he’s not frightening at all. The most terrifying about the story is that we might be complicit in animalising Merrick… that given the opportunity we too might have feared him.

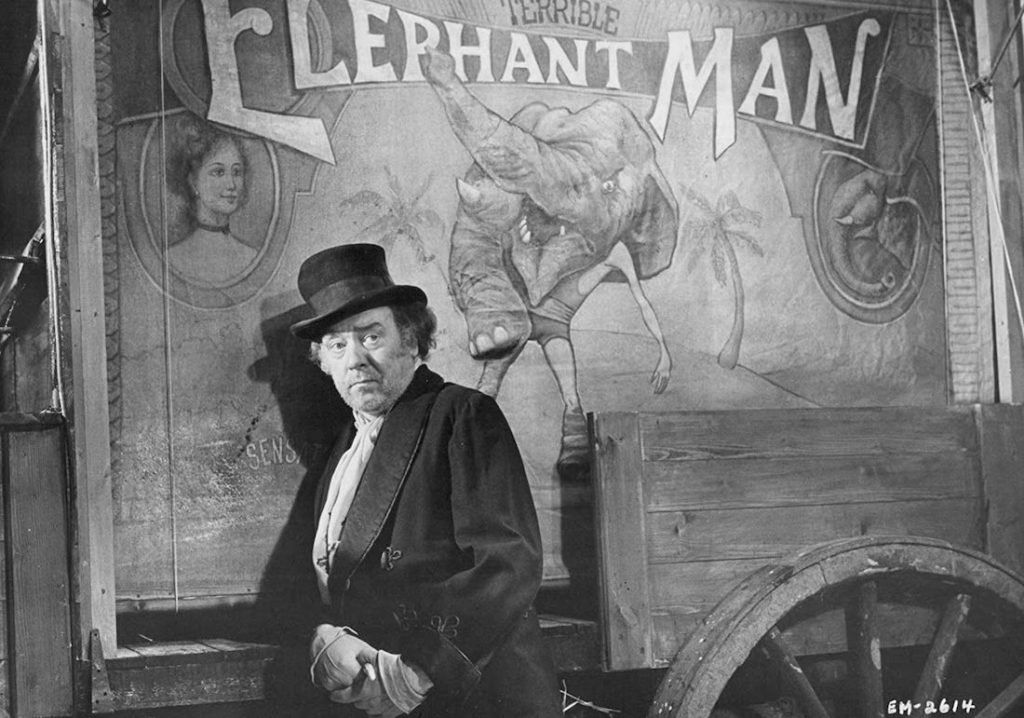

The Elephant Man can be a terrifying film for how unafraid Lynch is to depict the utter depravity of human behaviour. When we meet Merrick, he’s being kept in something that resembles a concrete dungeon by Mr Bytes (Freddie Jones), a deplorable but desperate man with nothing to his name but his ‘elephant man’. He barks orders at Merrick, beats him, and does everything besides treating him as a human being. In these corners of the city, where people and machines and animals are all exploited as a disposable resource, the exploited turn, in desperation, to taking advantage of those with even less than them. It’s a horrific representation of a people so deprived and ignored by its country that it is forced to cannibalise itself.

One scene, in which Merrick is assaulted by drunks in his room, is perhaps the most upsetting and distressing thing that Lynch has ever filmed. When we think of the person behind the dumpsters in Mulholland Drive (2001) or, indeed, the ‘experiment’ in Twin Peaks: The Return (2018), we’re struck by a horror that is uncanny. But Lynch’s most soul-disturbing images are often those which present a reality we recognise: Leland Palmer murdering his daughter, Frank Booth assaulting Dorothy Vallens, and a group of men torturing John Merrick. The surreal in Lynch’s work is the result of an inability to process violence and evil—when it’s stripped away we’re left with acts that are startlingly, horrifically real. Lynch’s forays into darkness in The Elephant Man are not enough on their own to be described as ‘Lynchian’—what defines this film as one definitively his is the dichotomy between darkness and light. And there’s so much light to be found.

It may sound reductive to simply call John Merrick a good man, but although there’s more to him than goodness, the idea of it defines him. He says it himself: “I’ve tried so hard to be good”. No other line in the film hurts as much as that one. It makes one ache with the weight of it, as simple as it is. Everything’s been a struggle for Merrick. The vulnerability of his statement suggests he’s been made to feel he isn’t good, and that he must work twice as hard to prove that he is. When he says it, the film itself seems to ache with us, as Frederick’s wife, Ann (Hannah Gordon), breaks down into sobs. In a city powered by cruelty and subjugation, where nobody can afford to ponder the concept of goodness, here’s a man who truly is good, terrified without reason that he isn’t.

Hurt’s performance is particularly demanding, posing a unique challenge: how do you act under layers upon layers of prosthetics? He’s forced to express almost entirely with his voice and body, and he does so with remarkable subtlety. His Merrick feels particularly small and timid, his voice filled with hopeful youth, his movements precise and delicate. In one of Hurt’s finest moments, he recites phrases he’s been taught by Treves to Francis Carr-Gomm (John Gielgud), the Governor of the hospital. As he struggles to find the correct words, he remains undeterred, but cries. He doesn’t sob—instead, the tears fall silently as he talks. It’d be a complex moment for an actor under any circumstances, but here it’s remarkable what Hurt achieves. Merrick’s fears, his eagerness, his gentleness, are all beautifully realised in one moment simply through voice and posture. The film asks us to connect with a non-traditional protagonist; Hurt’s astonishing performance ensures that we do.

Merrick’s uncertainty is mirrored in Treves’ anxieties. In moving Merrick into the hospital, and by positioning him as a medical curiosity to his colleagues and, unintentionally, the public, the kindly surgeon becomes consumed with worry that he’s not so far removed from the men who run the freakshows. Merrick fears that he doesn’t belong anywhere but the darkest pits of London; Treves fears that he’s no better than the men who dwell there. Both men’s fears are externalised in some of Lynch’s most striking images. It seems as if the city itself might gobble both men up. The blackened pipes that run under the city are constantly groaning, while steam shoots out like smoke from an invisible fire on every corner. During Britain’s industrial revolution, people were worked to death in droves, and so Lynch’s vision of London feels like a factory that produces not just metals, but bodies.

Shot beautifully in black-and-white by cinematographer Freddie Francis, the film’s visual style makes room for both brutal physicality and moments of otherworldly transcendence. Take, for instance, the images of Merrick’s dead mother’s (Phoebe Nicholls) floating seemingly amongst the stars, angelic and pure. They’re dreamlike fantasies, mythic characters that call back to The Lady in the Radiator in Eraserhead (1977), and hint towards Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks. Or the play that Merrick is brought to see, filled with sprites and angels, a representation of this strange new world he’s found himself in. Like all of Lynch’s worlds, it can be tragic and beautiful and is often both at the same time.

The Elephant Man is about the inevitability of tragedy, but it’s also about the ways in which we can give each other the dignity, friendship, and kindness to weather a storm. Lynch, contrary to popular belief, isn’t a pessimistic director. His films aren’t about the fact that we’re doomed to violence and pain, they’re about the ways in which we fall susceptible to them, and how, one day we might free ourselves of it all. There’s sadness, but there always is with Lynch—heartbreak might be the thing that binds his oeuvre together. More essentially, there’s a generosity of spirit and hopefulness that we can be good in The Elephant Man.

This film, along with The Straight Story (1999), is thought of to be the most atypical work of Lynch’s career. But I’m not so sure it is. One might look at The Elephant Man and wonder how it could be attributed to such an experimental and boundary-pushing auteur such as Lynch, but to perceive Lynch as only that is to miss so much of what makes him an enduring artist. On first look, it might be impossible to imagine him making a film such as this, but 40 years on it’s impossible to imagine it being anyone but David Lynch. Implementing a classical style that hints towards another great David—David Lean—and employing his sorrowful but pounding heart that beats for the people at the margins of society, Lynch’s The Elephant Man is some of his most fascinating and moving work.

The Elephant Man is a simple movie, ultimately. But its complexity lies in its execution. Between the unusual editing and fades-to-black, it might be hard if actors weren’t a giveaway to decide just when the film was made. There’s something oddly timeless and hypnotic about it. Being drawn into this world is when we begin to focus on what matters in this film. It’s not dramatic storytelling or even performance; it’s about placing ourselves amongst John Merrick and Frederick and Ann Treves to witness the extraordinary power of grace.

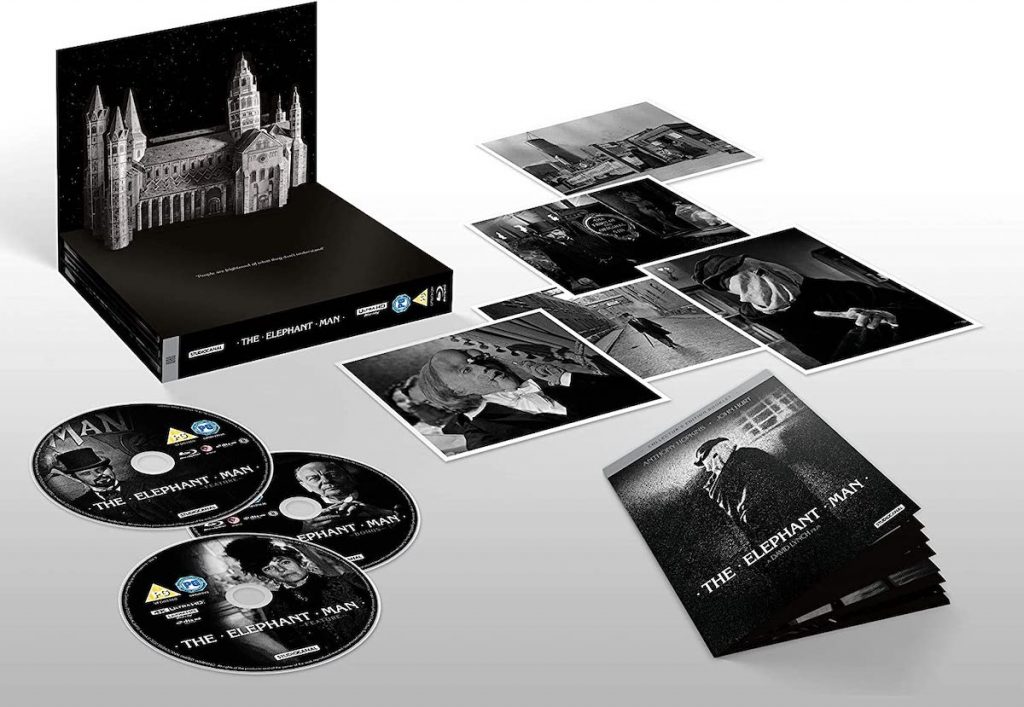

StudioCanal’s 4K restoration of the film is the best the film has ever looked. The beautifully designed sets, as well as location photography, feel vivid and textured, while the monochrome images are gorgeously subtle shades of grey. Much of the conversation surrounding 4K releases focuses on their vivid colours, which may leave some wondering whether black-and-white films are worth the 4K treatment. This release confirms the answer is an unequivocal ‘yes’.

It’s a dark film and this restoration recreates the natural lighting extremely well, making the scenes set in London’s backstreets truly enveloping. The sound mix in this new edition, however, is perhaps its greatest achievement. Lynch’s soundscapes are haunting; the knocks, drones, and groans each echoing like ghosts in this 4K release’s excellent sound mix.

director: David Lynch.

writers: Christopher De Vore, Eric Bergren & David Lynch (based on ‘The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences’ by Frederick Treves, and ‘The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity’ by Ashley Montagu.

starring: John Hurt, Anthony Hopkins, Anne Bancroft, John Gielgud & Wendy Hiller.