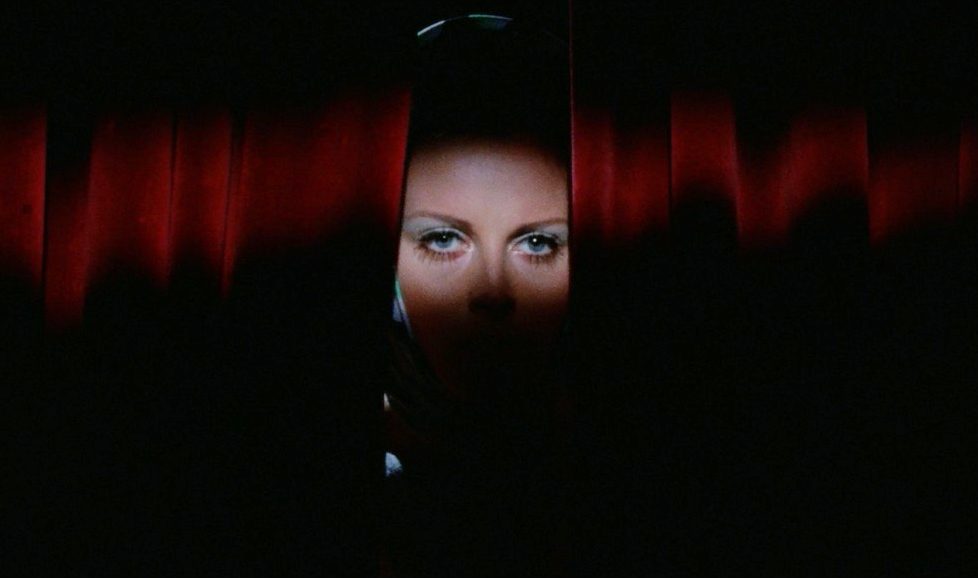

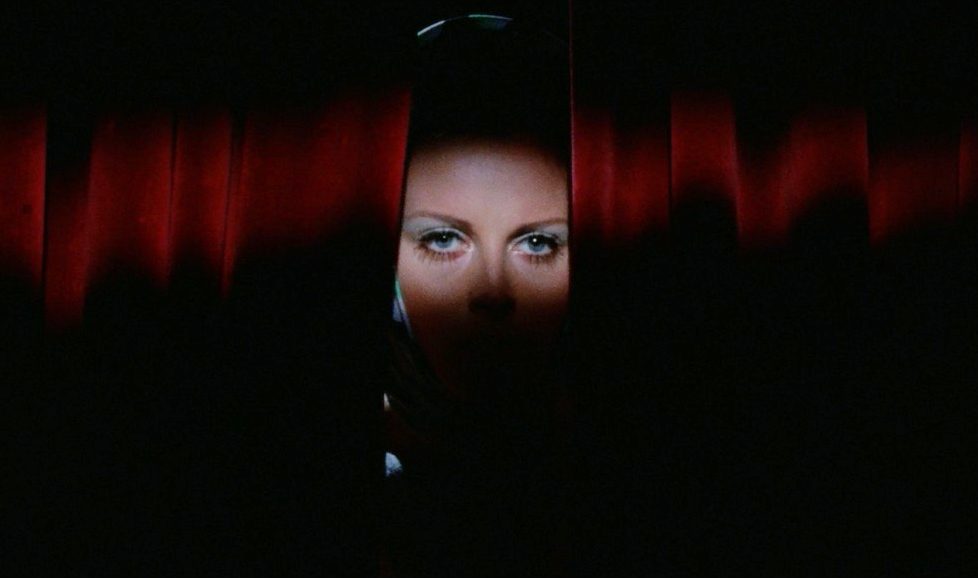

THE FORBIDDEN PHOTOS OF A LADY ABOVE SUSPICION (1970)

A triangle of friendship, love, sex, and, perhaps, murder. Minou is newly married to Peter, a businessman in debt as he works to bring a new product to market

A triangle of friendship, love, sex, and, perhaps, murder. Minou is newly married to Peter, a businessman in debt as he works to bring a new product to market

Not long ago, giallo was an obscure cult genre mostly dismissed by critics and mainstream audiences alike. So, it’s really cool that Arrow Video are helping the genre regain its standing and achieve overdue critical recognition. Luciano Ercoli’s The Forbidden Photos of a Woman Above Suspicion (1970)/Le foto proibite di una signora per bene really benefits from the high-definition Blu-ray treatment, which showcases its luscious colours and solid compositions in the originally intended Techniscope format.

Negative reviews have described the film as slow-paced—and that could be true, but compared to what? It doesn’t have the high body-count and extended, cleverly contrived murder set-pieces we have come to expect from a giallo but, really, there’s something significant happening or being said almost every minute. And in-between we get some gorgeous visual styling, as many a frame could be taken out of context and presented as a beautiful arrangement of forms that would bear critique alongside the works of famous abstract painters and structural photographers.

The film has sometimes been dismissed as dated. Well, it is dated. In nearly every aspect. Whether this is a good or bad thing will depend on the viewer and their mood. I’m a sucker for 1970s pulp cinema, and the Italian giallo is one of my go-to genres—my cinematic equivalent of comfort food. So, for me the cars—modern at the time, now classic; the fashions, on-brand back then, now quaint; and the décor, well, I grew up in a home with a curved orange sofa and purple carpeting… so its precise period detail strikes a chord with me.

The Forbidden Photos of a Woman Above Suspicion is one of those movies where its period detail has become one of its selling points. The art-school adage ‘depict the ordinary and time will make it extraordinary’ could well be applied. Not that the affluent lifestyles here were that ordinary back then. They were aspirational and at the same time cautionary. The characters are shown to be rich, successful, chic and stylish, but also deceitful and decadent. We can vicariously enjoy their high-society lifestyle whilst finding comfort in witnessing their punishment for having what we might not. This has been a central theme in many thrillers and features prominently in gialli of the 1970s.

The dialogue has aged beautifully, too. Casual comments from central characters will trigger our modern, politically-correct knee-jerk response. Feminists will be fuming. This only adds to the discomforting atmosphere and building sense of sexual menace. When a blade-wielding ‘maniac’ (Simón Andreu) accosts Minou (Dagmar Lassander) on a deserted beach at night, her main concern after the event is whether her new husband, Pier (Pier Paolo Capponi), would’ve still loved her if ‘anything had happened’. He comforts her by saying he believes that ‘nothing’ happened. So, being pinned to the ground by a stranger and having your dress cut open counted as nothing in the ’70s?

Minou neglects to tell Pier that the attacker is also blackmailing her and claims to have evidence that her husband’s murdered a business associate. She does, tentatively, ask if he has any problems at work… but he simply smiles and tells her not to worry her little head about that and, instead of a slap, he gets a smile and an affectional nuzzle.

Thing is, these puzzling attitudes in relationships were rife at the time, proliferated by the popular press as patriarchal dominance was feeling threatened by women’s lib. She doesn’t bother going to the police, because she thinks they wouldn’t believe her and it would be time wasted with pointless form-filling. One can imagine how vulnerable a woman could be in this macho society and completely understand why Minou drinks in the afternoon and is popping pills for her nerves.

When Minou recounts her ordeal to her best friend, Dominique (Nieves Navarro, credited here as Susan Scott), she makes light of the incident and, trying to cheer up her brooding pal, says that she longs to be jumped by a stranger in a secluded spot because it’s a compliment to a woman’s sex appeal. As she puts it, “you either like it and stay with him, or you don’t and dump him…”

In many ways it captures a transitional era, not least in gender identity and attitudes, and to quote the songwriter, Momus, in the pre-AIDS 1970s “sex was like a handshake between friends.” So maybe it wouldn’t have been all that strange when Dominique invites Minou back to her apartment to look at her latest batch of nudes and porn pictures she’s posed for… This leads the audience to the first plot twist when Minou recognises the male ‘model’ posing with her friend as the very same man from the beach…

The plot thickens when Minou reads in the newspaper that a powerful financier’s been found dead in bed. Inexplicably, the cause of death was embolism concurrent with rapid decompression—what divers term ‘the bends’. She remembers her attacker’s blackmail claim and is now inclined to believe it because her husband’s company makes diving equipment and had been seeking finance for an experimental decompression chamber…

As the epic title would suggest, the film plays out as more of a blackmail suspense story, in line with earlier Hitchcock thrillers. Indeed, it’s a Hitchcock film, The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934, 1956) that’s usually cited as the progenitor of the giallo, with Mario Bava’s Blood and Black Lace (1964) as the first ‘true’ representative of the genre. Bava’s film templated much of its tropes including the black-gloved killer, the inventive cinematography, the whodunit puzzle structure and the explicit murder set-pieces. After that, Dario Argento’s breakthrough The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) is given the lion’s share of the credit for defining the genre. Perhaps Forbidden Photos has been overlooked and remains underrated because it was made that same year?

Pulp cinema throughout the 1960s and ’70s was a very successful industry and producers were only interested in films that put bums on seats, but one defining feature of the Italian giallo is that they’re better than they needed to be. Giallo aficionados may be disappointed by the relatively low body-count here, but stylistically, it has much to offer.

Director Luciano Ercoli clearly has a vision. He may well be cashing-in on cheap exploitation films and the vogue for sexy thrillers. Certainly, he was trying to please distributors, but the film has undeniable style. This is achieved by extra care and attention, rather than a larger budget. An audaciously-framed shot doesn’t really cost any more than a boring one, but it does require directorial flair, skilled cinematography, imagination, and proper planning.

Considering this is Ercoli’s debut, it’s directed with clear conviction and control. He places great emphasis on composition, camera movement and colour palette. The cinematography of Alejandro Ulloa, a veteran of Italian pulp cinema, doesn’t let him down for a second.

Ercoli’s next two films would also be minor giallo classics: Death Walks on High Heels (1971) which includes similar themes of sexual malice, and Death Walks at Midnight (1972)—which may have been part-inspiration for the US giallo Eyes of Laura Mars (1978). They conclude Ercoli’s trilogy of important formative films, all starring the versatile Nieves Navarro, the handsomely ambiguous Simón Andreu, and penned by the great Ernesto Gastaldi.

Ernesto Gastaldi may well be a more influential figure in Italian pulp cinema than any director, with more than 125 writing credits that include such defining classics as Mario Bava’s The Whip and the Body (1963), his self-directed debut Libido (1965), Antonio Margheriti’s Long Hair of Death (1965), Romolo Guerrieri’s The Sweet Body of Deborah (1968), Umberto Lenzi’s So Sweet, So Perverse (1969), Giuliano Carnimeo’s The Case of the Bloody Iris (1972) and half-a-dozen of the most important gialli for Sergio Martino: The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971) which is arguably the finest example of the genre; The Case of the Scorpion’s Tail (1971) which typifies the jet-set giallo; All the Colors of the Dark (1972), a truly disturbing horror-giallo crossover: Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (1972) inspired by Edgar Allen Poe with perhaps the greatest title ever; Torso (1973), a notoriously sleazy slasher; and The Suspicious Death of a Minor (1975) in which he fuses giallo with another popular Italian crime genre, the poliziotteschi.

His story for Forbidden Photos is cleverly contrived and deliberately reveals clues in a carefully planned sequence. One thing gialli rarely offer is realism and believability and this is no exception, with glaring narrative conceits. On the surface, it may seem to have failed in its misdirection—I was certain I’d solved the puzzle by the half-way mark. And I had, sort of…. but then the narrative becomes an intellectual game, not unlike an episode of Columbo, where we all know who’s guilty but aren’t sure how it’ll play out. Gastaldi doesn’t disappoint and withholds a satisfying final twist for the last five minutes.

Dominique is the most interesting character and, for much of the film, seems both ambivalent and ambiguous. She’s a strong, sexy, stylish, independent woman living by her own means and successful on her own terms. This kind of liberated female became a stock character of the giallo at a time when women were all too often secondary to male leads in the mainstream cinema of the US and Europe. A giallo woman could be pro-active, she could be the one who reveals the culprit, solves the crime without depending on the help of a man. She could end up either victim or victor. Navarro, a model-turned-actress, is now recognised as an icon of Italian pulp cinema having starred in many classics. She makes her transition to gialli here, after appearing predominantly in Euro-westerns, with two of her earliest roles in the superb Ringo films for director Duccio Tessari.

Bohemian actress Dagmar Lassander, who shares the female lead, was fresh from filming Mario Bava’s A Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1970), though I’m not as convinced by her performance. She always looks to be acting. But this may be a clever device, because, for most of the movie, that’s exactly what’s happening. She’s pretending not to know what she knows, she’s hiding her suspicions, she’s putting on a brave face… not to mention the influence of narcotics and booze. So perhaps her less-than-convincing delivery is actually acting genius.

There are a few other familiar faces peppered throughout. Some viewers will recognise Pier Paolo Capponi as Spini, the superintendent of police in Argento’s The Cat O’Nine Tails (1971). For Osvaldo Genazzani, who plays the police presence here, Forbidden Photos marks one of his final few appearances, in a career that spanned five decades. Another star of the film that definitely deserves mention is, of course, Ennio Morricone’s fantastic score. He takes us on a musical tour from smoochy lounge jazz through some generic ’70s disco funk and into inventive discordant cacophony in one of his standout giallo soundtracks. If there’s one gripe I’d admit to with this fantastic release, it’s that there’s no isolated score. Or how about a bonus soundtrack CD? I know, it’s a licensing nightmare. It’s only a very minor complaint, so don’t let it deter you from (re)discovering this giallo gem…

director: Luciano Ercoli.

writer: Ernesto Gastaldi (story by Ernesto Gastaldi & Mahnahén Velasco).

starring: Pier Paolo Capponi, Simon Andreu, Dagmar Lassander & Susan Scott.